Written by Andy Ludlum, Library Volunteer

This was the moment they had been working towards for over 25 years.

Suffragists were confident that California women would win the right to vote in the 1896 statewide general election. National leaders saw California as a turning point, a chance to prove their movement could succeed beyond sparsely-populated Wyoming, Utah and Colorado, the only states at the time where women could vote.

California women had been pushing for the vote in every Legislative session since the first women’s suffrage meeting was held in San Francisco in 1869. In March 1895, the State Legislature submitted an amendment conferring full suffrage on women to be decided in a statewide referendum November 3, 1896. The timing was somewhat of a disappointment to women as the campaign would come at the same time as a hotly-contested election for President of the United States. The women also faced the daunting challenge of organizing a statewide campaign with national implications.

National suffrage leaders Susan B. Anthony and Anna Howard Shaw came to the state in March 1896 and remained until after the election in November. Anthony spoke once or more every day, including during the sweltering summer of 1896. She toured Central and Southern California, lecturing in halls, churches, parlors and schoolhouses. Sometimes she spoke from the rear platform of her train which was banked with flowers.

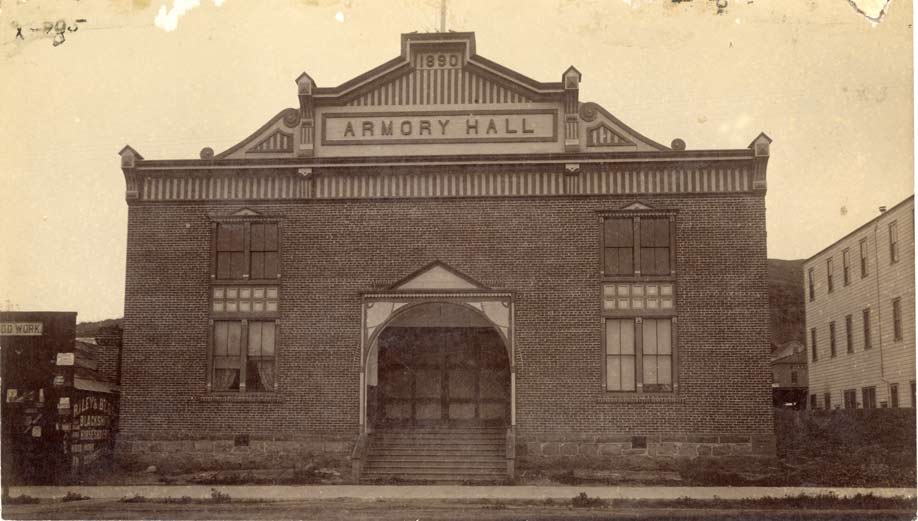

On Saturday night, October 17, 1896 Anthony packed Ventura’s Armory Hall for a 45-minute speech. The Ventura Free Press account noted the room was “filled to upmost capacity” despite the organizers charging a small admission fee (probably 10 cents) to cover the expense of the hall. The report concluded that Anthony’s words “sank deep into the hearts of her hearers, and the noble cause to which she has devoted the best years of her life will surely receive a decided impetus from her having been among us… We predict the vote for the 6th Amendment in Ventura County will show that the electors are not wanting in chivalry or a sense of justice.”

Shaw spoke at Armory Hall in April of that year. She was billed as “brilliant, logical, witty and immensely entertaining.” The suffrage-friendly Ventura Free Press went on to say, “It is hoped those who are not in favor of equal suffrage will come out and give themselves an opportunity to be converted.”

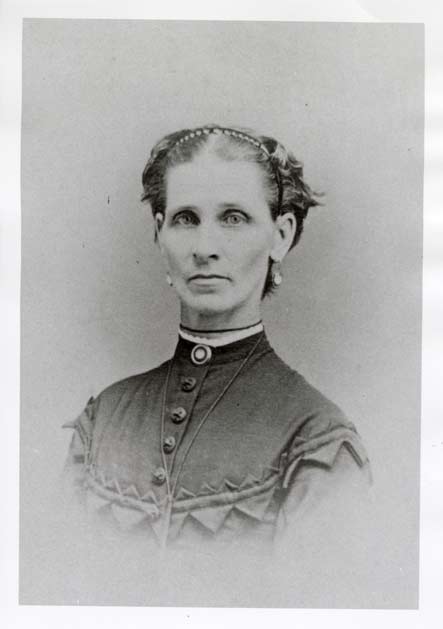

Adelaide Comstock figured prominently in the drive for women’s suffrage in Ventura County. Comstock lived 43 of her 88 years in Ventura and had been active in the movement from the early days. Comstock was a prolific author and poet whose words have been preserved in the Research Library’s copy of her “Poems, Reminiscences, Letters and Biographical Sketches”, among others.

In a letter to the editor of the Ventura Signal in 1882, she took to task Professor Goldwin Smith who had argued women were too emotional and incapable of making careful and wise political decisions.

“The idea that woman’s influence cannot be trusted in politics is a downright insult to the sex. Men of the lowest order…may vote without their right being even questioned; and their vote counts just as much as the best citizen in the state. Although they may have little more than brutish sense, and often more than brutish depravity, their status is…higher than that of the most refined and intelligent woman in the land…”

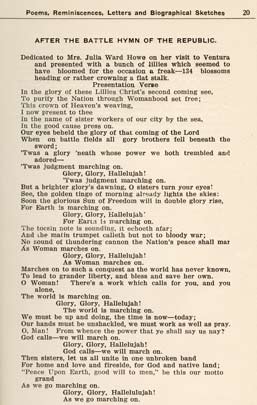

Music played an inspiring role in the 1896 campaign. Poet and author Julia Ward Howe became the rock star of her day after her poem, the “Battle Hymn of the Republic” was published in 1861 and quickly set the tune of a Civil War song called “John Brown’s Body.”

Suffragists adopted Howe’s Battle Hymn as the unofficial anthem of their movement. They created their own versions with words supporting a woman’s right to vote. Comstock’s “After the Battle Hymn of the Republic” was dedicated and presented to Howe along with a bunch of lilies during a visit Howe made to Ventura. Comstock’s “Battle Hymn” opens with these lines:

In the glory of these lilies Christ’s second coming see,

To purify the Nation through Womanhood set free;

This crown of Heaven’s weaving,

I now present to three

In the name of sister workers in our city by the sea,

In the good cause press on.

Glory, Glory Hallelujah…

…We must be up and doing, the time is now – today;

Our hands must be unshackled,

we must work as well as pray.

O Man! From whence the power that ye shall say us nay?

God calls – we will march on.

Glory, Glory Hallelujah!

God calls – we will march on.

In July 1896, as the Ventura City Band paraded on Santa Clara street, the Ventura County Convention of the Woman’s Suffrage League opened in Union Hall. Ida K. Spears, who was noted for “leading the work in Ventura County with pen and voice,” was elected president and Comstock was named treasurer.

In order to reach the men who would decide if women would get the right to vote, appearances were scheduled before almost any sort of club or organization. The women would enlist sympathetic fathers, husbands and sons to speak in front of their clubs and convince them to sponsor resolutions in support of the amendment.

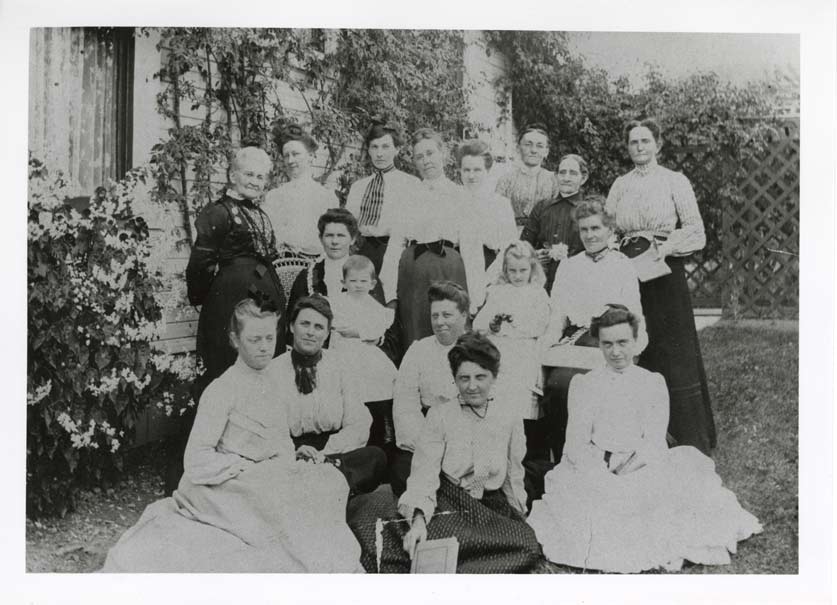

Women also banded together on their own. During the 1890’s hundreds of thousands of women joined women’s clubs with a variety of interests, including the right to vote. The largest of the women’s organizations was the Women’s Christian Temperance Union. The group was most concerned with the impact of alcohol abuse on women and families but came to adopt a broader social welfare program that supported women’s suffrage.

Although a great effort was made to keep the suffrage question non-partisan, it could not escape the effects of partisan politics. Nor could suffragists successfully distance themselves from their long-time supporters in the temperance movement.

Near the end of the amendment campaign, the California Republican party was threatened with loss of money and votes if it continued to support the suffrage amendment. The Chairman of the State Central Committee was notifying county chairmen not to permit women to speak at Republican meetings. The final blow came when the wholesale Liquor Dealer’s League resolved “to take such steps necessary to protect our interests.” One of these steps was to send a message to saloonkeepers, hotel proprietors, druggists and grocers throughout the state:

“At the election to be held on November 3, Constitutional Amendment No. Six, which gives the right to vote to women, will be voted on. It is in your interest and ours to vote against this amendment. We request and urge you to vote and work against it and do all you can to defeat it.”

By the close of the 1896 campaign, 250 papers in the state had declared editorially for women’s suffrage. Only 27 spoke openly against, most notably the Los Angeles Times, the San Francisco Chronicle and the Sacramento Record-Union.

The Presidential Election of 1896

The presidential campaign of 1896 was one of the most contentious in American history. Republican William McKinley faced Democrat William Jennings Bryan in a campaign defined by a great depression known as the “Panic of 1893.” The pragmatic McKinley stuck closely to bread-and-butter economic issues and avoided controversy such as alcohol use and a woman’s right to vote. McKinley was aware of women’s growing political influence and their power in the temperance movement, but he was not ready to fully endorse women’s suffrage.

California voters chose McKinley and rejected the women’s suffrage amendment. There were 110,335 for and 137,099 votes against the suffrage amendment.

It would be 15 years before California women would get another opportunity to win the right to vote.

The Vote Finally Comes for California Women

By 1911, only five states had approved giving women the vote. In some other states, women had partial suffrage and voted in local races, on bond issues and school-related matters.

Political conditions began to change in 1910 when a progressive Republican state administration came into power. Suffragists successfully lobbied the California Legislature to put the question before the voters once again as a constitutional amendment.

Saticoy school teacher Anna Hawley said in 1910, “We of comfortable homes, protected and cared for, cannot judge what the right of suffrage would mean to women who have to toil in sweatshops and other places for a living, perhaps toiling for a mere pittance.”

The general attitude of the public towards women voting was more “amused, indifferent and incredulous” than hostile according to suffrage leader Louise Wall. Suffragists made “hopeful and constructive” arguments in the streets and from automobiles to win over voters. They held mass rallies, picnics and small meetings. Once again, they addressed any audience they could find; congregations, unions, factory workers, women’s clubs. According to Robert Cooney’s summary of the 1911 campaign, the suffragists distributed over three million pieces of literature and over 90,000 “Votes for Women” buttons in Southern California.

Learning from 1896, suffrage leaders expected strong opposition from saloon and business interests who feared prohibition. So, they concentrated their efforts on the rural parts of the state. On election day, October 10, 1911, the amendment was soundly defeated in San Francisco and just squeaked by in Los Angeles. Resigned suffragists were starting to plan their next campaign when reports from rural counties began to trickle in, with votes in their favor. It took several days to count all the ballots, but in the end, suffrage had passed by only 3587 votes. In Ventura County the amendment was defeated by 40 votes.

With the passage of the California amendment, the number of women with full suffrage in the United States doubled overnight. But until 1920, a woman’s right to vote was still determined by where she lived. With more victories, suffragists finally had political power Congress could not ignore. When Tennessee became the 36th state to ratify the 19th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution on August 18, 1920, all American women finally had the vote, the result of over 50 years of work by suffragists here in Ventura County and across the nation.

While Adelaide Comstock lived to see Ventura County women vote, she died two years before the ratification of the 19th Amendment. The interested reader may visit the MVC Library to read her poetry and other writings, including a 32 page book on San Buenaventura Mission.

Make History!

Support The Museum of Ventura County!

Membership

Join the Museum and you, your family, and guests will enjoy all the special benefits that make being a member of the Museum of Ventura County so worthwhile.

Support

Your donation will help support our online initiatives, keep exhibitions open and evolving, protect collections, and support education programs.

Bibliography

- Anthony, Susan B., and Ida H. Harper. The History of Woman Suffrage, Volume IV. The Hollenbeck Press, 1902.

- Comstock, Adelaide. Reminiscences, Letters and Biographic Sketches. 1923.

- Comstock, Adelaide. “Mission San Buenaventura.” Ventura County Historical Society Quarterly, Vol. XXVI, no. 4 (Summer 1981).

- Comstock, Adelaide. “Woman Suffrage, Letter to the Editor.” The Ventura Signal, May 6, 1882.

- Cooper, Donald G. “The California Suffrage Campaign of 1896: Its Origin, Strategies, Defeat.” Southern California Quarterly, Vol. 71, no. 4 (Winter 1989).

- Morgan, H. Wayne. “The View from the Front Porch: William McKinley and the Campaign of 1896.” Lecture presented at the Rutherford B. Hayes Presidential Library and Museum. 2001. https://www.rbhayes.org/hayes/the-view-from-the-front-porch-william-mckinley-and-the-campaign-of-1896/.

- Newman, Carolyn. Ventura Women. 1996.

- Nunis Jr., Doyce B. Women in the Life of Southern California. Historical Society of Southern California, 1986.

- Phillips, Irene. Women of Distinction. South Bay Press, n.d.

- “The Poinsettia Club of Saticoy.” Ventura County Historical Society Quarterly, Vol. 32, no. 1 (Fall 1986).

- Smith, Goldwin. “Woman Suffrage; Some Very Sensible Remarks on a Very Grave Subject.” The Ventura Signal, March 18, 1882.

- Swartz, Hunter. “Where women could vote in 1919.” The Washington Post. 2015. https://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/govbeat/wp/2015/01/16/where-women-could-vote-in-1919/?noredirect=on&utm_term=.0599ef93433c.

- Ventura Free Press. “Equal Suffrage Convention.” April 3, 1896.

- Ventura Free Press. “Equal Suffrage. The County Convention of Woman Suffragists.” July 31, 1896.

- Ventura Free Press. “Woman’s Suffrage Meeting.” October 23, 1896.

- The Ventura Signal. “Woman Suffrage.” May 6, 1882.