By Museum Volunteer Andy Ludlum

On New Year’s Day 1919 Phillip Van der Meide, the manager of Ventura’s bath house said that after 17-years of trying, a spectacular new bath house would open its doors in the next month. Van der Meide said the bath house was already completed but opening in February would allow the public time to get over its fear of attending “places where crowds gather.” What Van der Meide didn’t know yet was that the opening would be delayed another four months as Ventura was experiencing its second wave of influenza in one of the deadliest epidemics in human history.

Modern readers probably don’t appreciate that Ventura’s bath house was more than a pool or “plunge.” It was an all-included public gathering place with private baths and showers, locker rooms, more than 400 dressing rooms, a hair salon, a large auditorium with a dance floor, a cigar room, a sun parlor and “roof garden”, a nursery, and a movie theater.

Spanish Flu

In 1919, with the bath house completed, hundreds of people were expected to gather in this new source of civic pride. But people were afraid to be around each other because of the flu. In the spring of 1918, an influenza outbreak spread worldwide from Army camps in Kansas. With World War I still raging, parts of the U.S. and Europe fell victim to this fast-spreading, unusually severe form of flu. It was wrongly named the Spanish flu because it was first reported by a newspaper in Madrid. Wartime censors, eager to maintain morale, minimized reports of illness and deaths in the U.S. and did nothing to correct the misimpression. About one in four Americans got the flu and 675,000 died. Twenty to 50 million people died worldwide. Ventura doctors reported the city’s first four cases of the flu on October 13, 1918. Ten days later, there were 35 new cases and all theaters, pool rooms, schools and churches were ordered to close. Soon thereafter a mask law went into effect. Eventually the number of cases declined, and public places reopened. The Ventura Daily Post and Daily Democrat labeled it a “harvest of death” and pointed out that flu deaths had doubled in the past year. Of the 147 deaths in Ventura in 1918, 50 were the result of influenza. Ventura in 1918 had a population of about 4,000.

Van der Meide couldn’t have missed the ominous warning signs on the front pages of Ventura’s papers nearly every day during January of 1919. There would be a daily count of the number of new flu cases. And there were the front-page obituaries like the one in the January 7th Ventura Daily Post and Daily Democrat on the influenza death of Forrest Willison. It reported the well-liked 23-year-old had worked for various local merchants and had “made an effort to get into the service of his country, but not being of robust constitution, he failed to make it.”

The worst came on January 9th, when almost all public places were shuttered. Citing an outbreak more severe than that of October 1918, city trustees, the Board of Education, and the Board of Health issued an order closing all schools, churches, theaters, pool halls and all other places where people would gather. Health officials were alarmed: 36 new cases were reported in one day, more than on any single day during the October outbreak. A quarantine was imposed in every house where flu was reported. Efforts were made to keep children at home and off the streets. The reporting on the number of flu cases was probably confusing to most readers. One day there would be 26 new cases, followed by an optimistic 12 the next day. But that was immediately followed by 35 new cases the following day with the pronouncement that there was “no indication of a decline in the epidemic.” The Ventura Daily Free Press said there were only 17 new cases on January 14th but added “the continuous new cases of the past week have been so many that the city is now badly afflicted. Scores of homes now have cases… several deaths have occurred in the past week. 21 houses under quarantine in Oxnard.” On the same day, The Ventura Daily Post and Daily Democrat reported Moorpark was the only section in the county where there was no flu.

On January 16th, while reporting 24 new cases of the flu, the Daily Post and Daily Democrat stated Ventura bath house manager Van der Meide “was in Los Angeles yesterday attending the meeting of the Southern California Bathhouse Association. Ventura’s bath house is one of the very finest of its kind in southern California. The date of the opening will be sometime next month, if the flu permits.” There would not be another mention of the bath house opening in any of the papers until March.

The Outbreak Finally Begins to Ease

As January waned, the number of new flu cases slowly declined. But even with the daily number of new cases approaching single digits, readers must have been shocked to see four flu death obituaries on the front page of the January 18th Daily Post and Daily Democrat. Finally, on Wednesday, January 22nd, for the first day since October 13, 1918 not one new case of influenza had been reported. The next day, the Board of Health declared the flu epidemic was over in Ventura. Churches and other public gathering places opened at 6 a.m. Sunday. The quarantine rule remained in effect and city officials passed an ordinance making it a misdemeanor not to report cases of influenza. Schools opened on Monday, for the first time in three weeks. The Daily Free Press reported, “In the grammar schools all teachers reported for duty and the attendance was large. The same was true of the high school.” By the end of January, all towns in Ventura County reported the number of flu cases were falling off, except in Santa Paula which was the last to be hit with the epidemic. It was also reported that all 50 residents of Santa Cruz Island had come down with the flu.

The Business of Building a Bathhouse

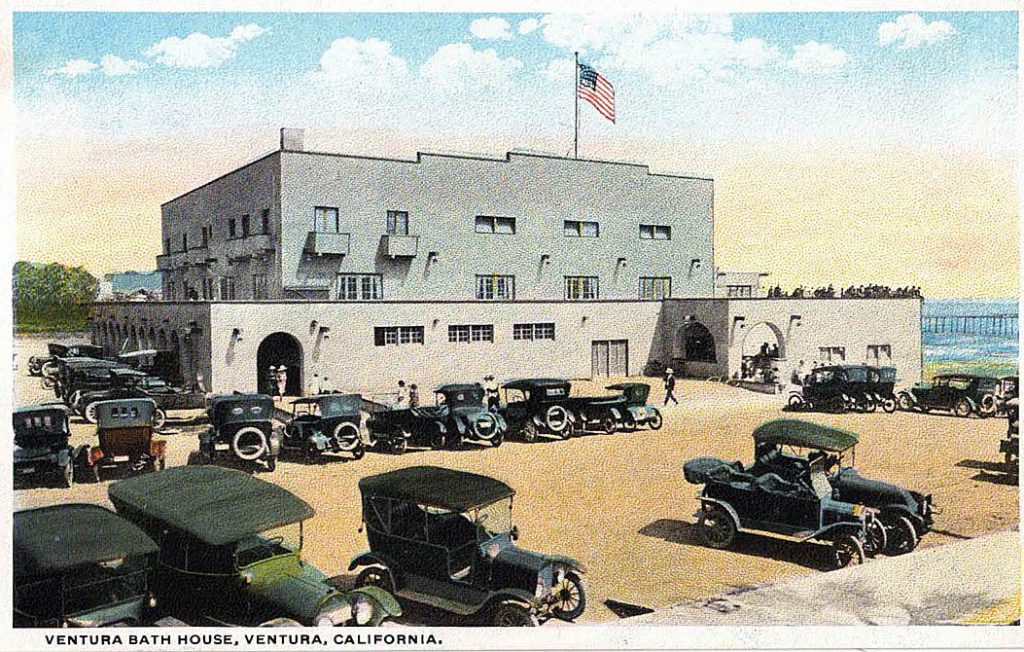

While life in Ventura was returning to normal, the continued delay in opening the bath house was just another chapter in its rocky history. Years earlier, in 1902, the Ventura Street Fair committee wound up with surplus funds from the annual celebration. They used the money to purchase the east half of the block at the foot of California Street and designated it as available for anyone who would build a bath house. In 1911 the Ventura Daily Free Press editorialized that a “bath house is one of the crying needs of the town.” Four years later the Chamber of Commerce and the Merchant’s Association urged the city to provide funds for the bath house by issuing bonds. Chamber of Commerce President James B. Blackstock noted that Ventura already had the finest courthouse, the finest hospital, the finest schools and the finest people in the state. He added that the city “has the finest beach on the coast, but that as an asset is practically useless, because we do not take advantage of what we have.” He said $1,000 had already been raised for a bath house and it would be easy to raise $5,000. He proposed turning the money over to the city and then requesting the city raise the balance of the funds. The Daily Free Press reported, “For many years the Chamber of Commerce has schemed and contrived for some plan whereby capital could be induced to invest in such a venture. After all these years, after every possible effort was made to induce outsiders to erect a building…the people of Ventura, tired of waiting, raised the money themselves.” Van der Meide presented a successful plan to the Chamber of Commerce and the Merchants Association to come up with the money needed for the bath house. The first plan called for a $25,000 building on the California Street site. But with the desire to create “the pride of the city,” the bath house grew in scope and grandeur. The building was finally completed at a cost of $75,000, approximately $1.2 million today.

A.L. Hobson, Father of the Bath House

Funding the bath house without outside investors was a monumental task. Shares were sold in the Ventura Bath House Company. Leading the company’s board of directors was a man who came to be known as “the father of the bath house,” A.L. Hobson. Abram Lincoln Hobson was a prominent Ventura businessman and philanthropist. Hobson and his brother William owned the Hobson Brothers Meat Packing Company at 235 West Santa Clara Street. (The building stands today. In 1973 Patagonia opened its first store in the old meat packing plant.) Hobson and his brother were at the forefront of the subdivision fever of 1920s Southern California. To create new farmland, the brothers directed river silt through levees and gates which led to the development of Pierpont Bay and ultimately the creation of the Ventura Keys and Ventura Harbor. Hobson was a visionary promoter of the oil industry in Ventura and helped trigger the county’s oil boom of the 1920s. When he died in 1929, his obituary called him the “father of the oil field.” Hobson was prominently involved in creating the Ventura County Fair Grounds, the Elks Lodge on Ash Street, the Masonic Temple on Santa Clara Street, and Ivy Lawn Cemetery. In leading the Ventura Bath House Company, Hobson’s financial investment, untiring effort, unfailing interest, and inspiration were cited for the success of the bath house by the Daily Free Press. It was his “indomitable energy (that) gave the project its start when all others had failed. It was his tenacity and personality, at times when breakers loomed and wreck seemed imminent, that made success of evident failure.”

Bath House Opening Plans Revealed

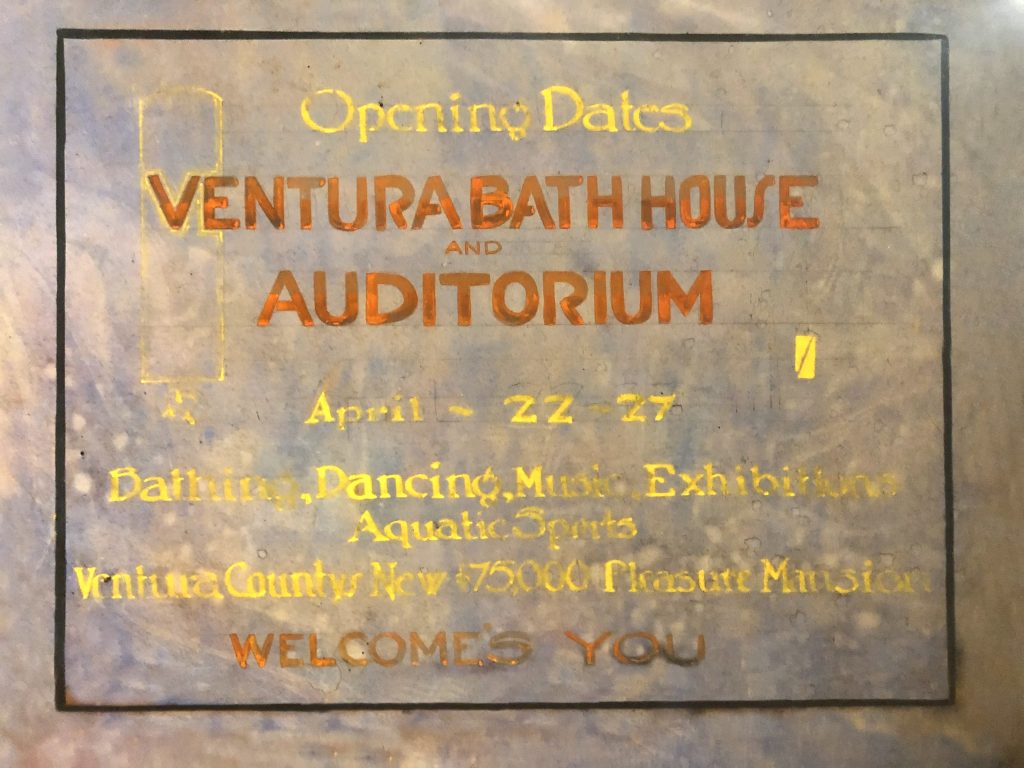

On Thursday, March 4, 1919 there was a banner across the top of the front page of the Daily Free Press; “Ventura’s New Bath House Will Be Opened on April 21.” Bathhouse Company director and manager Van der Meide was in Los Angeles to secure acts for the opening celebration which would last for several days. The company also completed lease arrangements with Van der Meide. He would pay the company 7 percent for its $75,000 investment for ten years. The Free Press noted “the bath house, though completed weeks ago, has not been opened because of the influenza epidemic and other causes.”

Throughout March and into April, the newspapers and local businesses engaged in almost constant promotion of one of “the most important celebrations in the history of Ventura.” The Ventura Daily Post and Daily Democrat reported on March 5th the “amusement resort” would open with a week of gala events, April 22-27. “Some of the world’s greatest swimmers will come to participate in the opening for the pool here is said to be one of the very best found in the United States.” On March 21st the paper reported the bath house would be much more than a spectacular “plunge” and would also include a “large beautiful auditorium so built and equipped that practically every type of public ensemble will be possible. Conventions, public installation of officers for fraternal orders, banquets, musicals, balls, receptions are a few of the possibilities.” Some of the articles were clearly more advertisement than news. One described how the “lady of today must look to appearance with as much concern when she adorns herself for a dip in the plunge…as when she prepares to attend the ball.” It added that Manager Van der Meide intends “to have a selection of bathing suits for sale at the new bath house, for the accommodation of those who do not wish to rent.”

The flu had not entirely disappeared, but it was no longer causing the fear and panic of the past January. In early April, the county health officer told the Board of Supervisors that a milder influenza was springing up in two parts of the county, Moorpark and Montalvo.

Ventura Merchants Sell Tickets to Bath House Opening

As the big day approached, details of the opening week’s events were revealed, and ticket sales began. Big events were planned for the first two nights of the opening week, one was informal, the second formal. On the second night, the members of the board of the Ventura Bath House Company would host a reception and formal ball to welcome the public to the new bath house. The Daily Free Press noted, “For the comfort of those who do not wish to participate in the reception and ball, but wish to take in the entertainment and ball as spectators, space and seats have been provided specially in the balcony. Admission charge will be one dollar, including the war tax.”

Beginning in 1917, event admissions were one of many things taxed to pay for the war effort. World War I cost the U.S. a staggering $32 billion. The War Revenue Act taxed many every-day items including liquor, cigars, perfume, transportation and even telegraph and radio messages. A one cent tax was paid on every 10 cents of an admissions charge. While the shooting had stopped on November 11, 1918 with the signing of the armistice with Germany, the war would not officially end until June 1919 with the signing of the Treaty of Versailles.

Ventura Retail Merchants Association members placed leaflets containing the complete program of the bath house and auditorium’s opening week in their stores. Stores sold 300 reduced price ticket books offering 40 baths for $10. This was 10 cents off the regular plunge admission and included suits, towels and the use of the dressing rooms and showers. Ventura business owners also supported the idea of installing ornamental lights on California Street from Santa Clara Street to the beach, giving a lighted way from the courthouse to the bath house. By the time bathhouse ads were in the papers in April, the words “Follow the Lights” were featured. By Friday, April 18th, the Daily Post and Daily Democrat reported “only a limited amount of space and seats are available for the spectators on the opening nights.” On that Friday, the newspaper began running a front-page banner that would continue for the next week: “Ventura’s Amusement Week – April 22-27 – Bathhouse Opening Dates.”

Bath House Opens to Large Crowds and Rave Reviews

On the day before the opening, the Daily Free Press said the new bath house would mark a new era in Ventura’s development. The plunge would open for bathers at 10 a.m. Spectators would be offered swimming and diving exhibitions during the day free of charge. During an evening dedication ceremony, Bath House Company President Hobson would present Manager Van der Meide the keys to the bath house and formally transfer management. They were to be entertained by dancers led by Norma Gould and singers, Mr. and Mrs. Howard Cavanah, accompanied by Reginald W. Martin at the piano.

The Daily Post and Daily Democrat gave the first opening night rave reviews. “Dreams about a bath house have been many, but it is certain that few, if any of them, ever equaled the splendor, the exquisite good taste of the reality – the reality that stood bathed in mellow light before the interested eyes of those who thronged the mezzanine floor or the ball room last evening.” The paper continued with its almost poetic praise, “It began at 10 a.m. yesterday and all day the magnificent plunge echoed to the merry shouts of bathers. At 8 o’clock the bath house was lighted up and hundreds of electric lights, most admirably subdued and arranged, blossomed into radiance. From the great flares outside, lighting up the stern Spanish walls and arches and drifting out over the night waters of the channel, to the wonderful antique bronze chandeliers in the cream and mahogany ball room, the bath house, illuminated, was a thing of beauty. To music furnished by the Bates Orchestra, long popular with local audiences…several hundred couples were on the floor during the evening and by 10 o’clock standing room for spectators was at a premium. By the French doors that flank the south side of the building a carpet was spread and there the bare-foot dancers, in filmy and symbolic costumes, went through their steps under the hectic hues of the spotlight.”

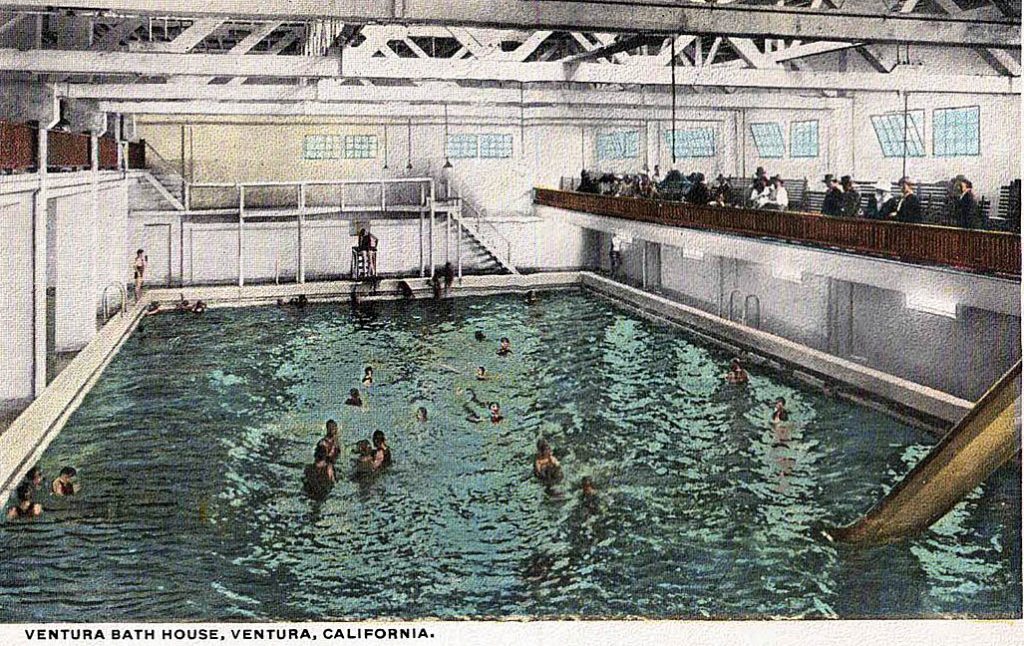

Newspaper Tour Behind the Scenes of the New Bath House

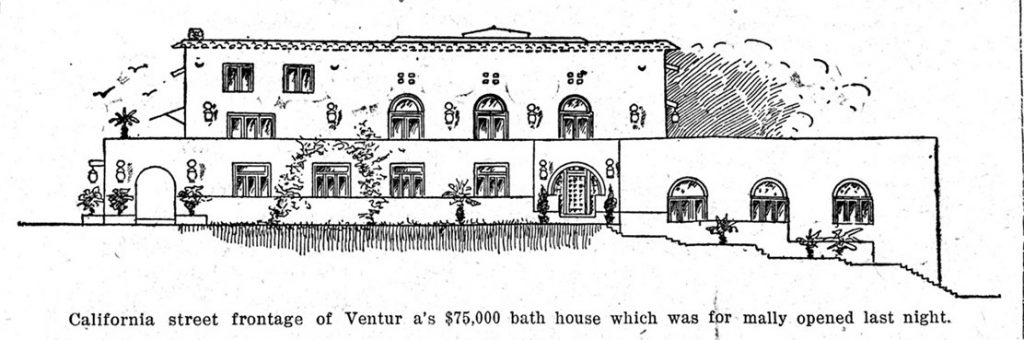

The Daily Free Press called the bath house the finest on the Pacific Coast and only equaled by bath houses in San Francisco and Santa Cruz. The paper presented a detailed tour of the bath house and auditorium on April 23rd. The building “is of Spanish-Moorish architecture and occupies the site of the bluffs above the beach. It is 140 x 185 feet in dimensions. The plunge occupies the level of the beach, the dressing rooms and balcony the level of the block, the auditorium roof garden, reception and refreshment room are one story above, while a third story in front is taken up by living apartment of the manager, the moving picture operating room and the nursery. The plunge is 45 x 100 feet in dimensions. The floor of the plunge is called a ‘spoon bottom,’ three and ½ feet to nine feet deep. The plunge can be filled with either salt or sulphur water. The sulphur water is obtained from artesian wells on the site. Water from the ocean…flows in by gravity and the tank is emptied in the same way. A motor driven centrifugal pump with a capacity of 750 gallons per minute fills the plunge. The water is heated by a…boiler fitted…with a capacity of 25,000 gallons per hour. It requires six hours to fill the big tank and three hours to empty and clean it.”

The pool had springboards, high dives and a slide. The plunge had lights beneath 4′ x 6′ glass plates on the bottom. Adjoining the pool was a “hairdressing parlor” and dressing rooms, separated by a concrete wall. There were 115 dressing rooms for women and 300 for men. Each section had private baths with hot and cold sulphur, salt or fresh water as well as lavatories and showers. There was a locker room with 100 individual lockers for suits and towels. A laundry room featured washers and a drying room with a hot air circulating system that not only dried the suits but heated the dressing rooms. On the same floor was a “gent’s smoking room.”

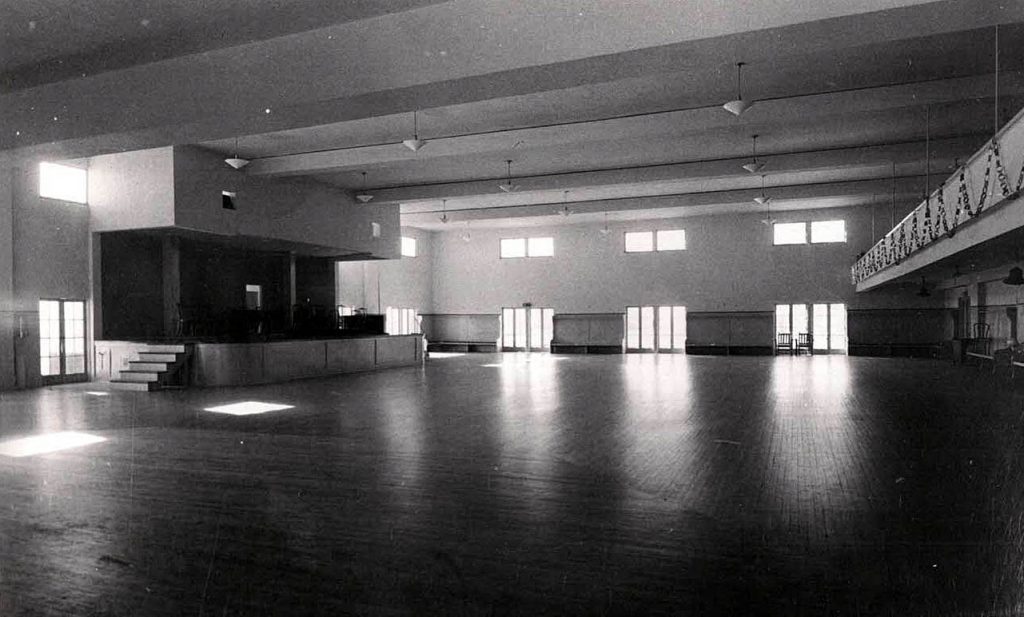

The auditorium was entered through a lobby and reception room with big fireplaces. A staircase led to the mezzanine floor and a 70 x 125-foot auditorium. It had a maple floor and was decorated in cream and gray and brown. There was a movable orchestra platform with a Steinway concert grand piano. The room had an indirect lighting system with antique brass chandeliers. The mezzanine floor had 360 opera chairs.

Hobson and Van der Meide Lead the Grand March

The second night of the bath house opening week was “Director’s Night” when directors of the Bath House Company hosted a grand society ball. The Daily Post and Daily Democrat called the evening “strictly society” and noted boxes along the western wall were taken up by “three of the most prominent families in the county” along with 25 to 30 of their invited guests. Mr. & Mrs. A. L. Hobson were in the center box. To their left were Mr. & Mrs. Adolfo Camarillo. On the right were Mr. & Mrs. Charles Collins Teague of Santa Paula. Other boxes were assigned to notables from throughout the county. As the Ventura Citizen’s Orchestra played, Hobson and his wife, followed by Van der Meide and his wife led 100 couples in a grand march into the ballroom. There they were entertained by the famous contralto Estelle Heartt-Dreyfus. Sherman D. Thacher of Ojai spoke, pointing out that the last time he spoke in Ventura was when a group of boys was leaving “for the service in the dark days of the selective draft.” He was referring to November 1917 when, as the Free Press recalled, there were “pitiful processions to the trains from the courthouse, the local band playing its proudest music to keep up the courage of the boys and their parents.” Thacher said it was only fitting the formal opening of the bath house “should be at this time and that the boys be welcomed back to scenes of happiness and festivity.”

The opening week’s festivities ended with a Sunday event focused on the plunge. There were races and diving exhibitions, including 7-year-old Cameron Coffee, a world champion boy diver. An eight-year-old girl, Norah Moore, performed two lifesaving carries of a full-grown woman. The Daily Post and Daily Democrat reported Sunday’s event drew record crowds and a least 500 people had to be turned away.

The bath house and auditorium would continue to be a popular entertainment and party venue for many years. Touring bands would play in the packed auditorium on Wednesday and Saturday evenings. “Crooner” Rudy Vallee, who was considered the “Elvis” of the 1920s and 30s sang in the auditorium through his signature megaphone. After World War II, tastes changed and fewer people came to the bath house. It fell into disuse and was abandoned. It was demolished in the 1950’s. You can still visit the site of the bath house at the foot of California Street at the Promenade, approximately where the parking garage is located.

Make History!

Support The Museum of Ventura County!

Membership

Join the Museum and you, your family, and guests will enjoy all the special benefits that make being a member of the Museum of Ventura County so worthwhile.

Support

Your donation will help support our online initiatives, keep exhibitions open and evolving, protect collections, and support education programs.

Bibliography

- Flu Aids Harvest of Death Here. “The Ventura Daily Post and Daily Democrat.” January 3, 1919.

- Lozada, Carlos. “The Economics of World War I.” The National Bureau of Economic Research. Accessed February 6, 2020. https://www.nber.org/digest/jan05/w10580.html.

- “Rudy Vallée.” Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia. Last modified November 24, 2002. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rudy_Vall%C3%A9e.

- Ventura Daily Free Press. “”Flu” Ban Off, Conditions Are Again Normal.” January 27, 1919.

- Ventura Daily Free Press. “Directors Night at Bath House Successful Affair.” April 24, 1919.

- Ventura Daily Free Press. “Flu Epidemic Not So Bad Reports Show.” January 14, 1919.

- Ventura Daily Free Press. “Plunge Draws Big Sunday Crowd.” April 28, 1919.

- Ventura Daily Free Press. “Program for Bath House Opening.” April 12, 1919.

- Ventura Daily Free Press. “Ventura’s Fine New Bathhouse Will Open on Tuesday.” April 21, 1919.

- Ventura Daily Free Press. “Ventura’s New Bath House Will Be Opened on April 21.” March 4, 1919.

- Ventura Daily Free Press. “Ventura’s Splendid Bath House Formally Opened to the Public.” April 23, 1919.

- Ventura Daily Free Press. “Welcome Home Our Soldier Heros.” April 28, 1919.

- The Ventura Daily Post and Daily Democrat. “16 New Cases of Influenza Tuesday.” January 15, 1919.

- The Ventura Daily Post and Daily Democrat. “26 New Cases of Flu Yesterday.” January 10, 1919.

- The Ventura Daily Post and Daily Democrat. “35 New Cases of Flu Yesterday.” January 12, 1919.

- The Ventura Daily Post and Daily Democrat. “April 22 is Date Set for Opening of Bathhouse.” March 5, 1919.

- The Ventura Daily Post and Daily Democrat. “Attends Meeting of Bathhouse Men.” January 16, 1919.

- The Ventura Daily Post and Daily Democrat. “Bathhouse Jammed With Sunday Crowd.” April 29, 1919.

- The Ventura Daily Post and Daily Democrat. “Bathhouse Leaflets Widely Circulated.” April 13, 1919.

- The Ventura Daily Post and Daily Democrat. “Bathhouse Opening to be Big Event.” March 21, 1919.

- The Ventura Daily Post and Daily Democrat. “Bathhouse Tickets Sell in Good Shape.” April 5, 1919.

- The Ventura Daily Post and Daily Democrat. “Bathhouse Will Open in February.” January 1, 1919.

- The Ventura Daily Post and Daily Democrat. “Big Crowd at Bathhouse Opening.” April 23, 1919.

- The Ventura Daily Post and Daily Democrat. “Brilliant Ball Marks Second Night of Bathhouse Opening.” April 24, 1919.

- The Ventura Daily Post and Daily Democrat. “Crack Swimmers of West Will be Here April 27.” April 10, 1919.

- The Ventura Daily Post and Daily Democrat. “E.F. Bond Passes Away of Influenza.” January 18, 1919.

- The Ventura Daily Post and Daily Democrat. “Eleven New Flu Cases Yesterday.” January 18, 1919.

- The Ventura Daily Post and Daily Democrat. “Epidemic Again Closes Ventura.” January 9, 1919.

- The Ventura Daily Post and Daily Democrat. “Epidemic Here Still Maintains Pace.” January 16, 1919.

- The Ventura Daily Post and Daily Democrat. “Everyone Qualifies for Flu on Island.” January 31, 1919.

- The Ventura Daily Post and Daily Democrat. “Flu Ban to be Lifted in This City on Sunday.” January 24, 1919.

- The Ventura Daily Post and Daily Democrat. “Flu Holding Up Same Old Clip.” January 17, 1919.

- The Ventura Daily Post and Daily Democrat. “Flu Situation Better Over County.” January 30, 1919.

- The Ventura Daily Post and Daily Democrat. “Flu Situation in Good Shape Here.” January 23, 1919.

- The Ventura Daily Post and Daily Democrat. “Forrest Willison Dies of Influenza.” January 7, 1919.

- The Ventura Daily Post and Daily Democrat. “Get Tickets for Opening Night.” April 18, 1919.

- The Ventura Daily Post and Daily Democrat. “Great Time at Bathhouse Opening.” March 29, 1919.

- The Ventura Daily Post and Daily Democrat. “How Much is Your Bath Anyhow?” April 9, 1919.

- The Ventura Daily Post and Daily Democrat. “Joe Stuart Dead of Influenza.” January 18, 1919.

- The Ventura Daily Post and Daily Democrat. “Many Schools Still Closed From Flu.” January 26, 1919.

- The Ventura Daily Post and Daily Democrat. “Merchants Have Bathhouse Tickets.” April 3, 1919.

- The Ventura Daily Post and Daily Democrat. “Mild Flu in Some Localities.” April 3, 1919.

- The Ventura Daily Post and Daily Democrat. “Miss Esther Basset, Teacher, Dead of Flu.” January 18, 1919.

- The Ventura Daily Post and Daily Democrat. “Moorpark Without Any Flu Yet.” January 14, 1919.

- The Ventura Daily Post and Daily Democrat. “Mrs. Lee Thompson Dead of Influenza.” January 18, 1919.

- The Ventura Daily Post and Daily Democrat. “Not a Single Case of Influenza Here.” January 22, 1919.

- The Ventura Daily Post and Daily Democrat. “Steady Decline in Flu Situation.” January 19, 1919.

- Ventura Free Press. “”Flu” Cases in Ventura Now Show Some Decrease.” January 11, 1919.

- Ventura Free Press. “To Urge Bonds for Bath House, Committees Boost Plan, Citizens United on Proposition.” September 24, 1915.

- Ventura Free Press. “Ventura Should Provide a Bath House and Plunge.” July 14, 1911.

- “Ventura Walking Tour.” In Keys to the County, Touring Historic Ventura County, 28. Ventura: Cherie Brant, in collaboration with the Ventura County Museum of History & Art, 2006.

- “Ventura-Pier-Interpretive-Panels.” Ventura, CA | Official Website. Accessed February 6, 2020. https://www.cityofventura.ca.gov/DocumentCenter/View/3110/Ventura-Pier-Interpretive-Panels-PDF?bidId=.