By Library Volunteer Andy Ludlum

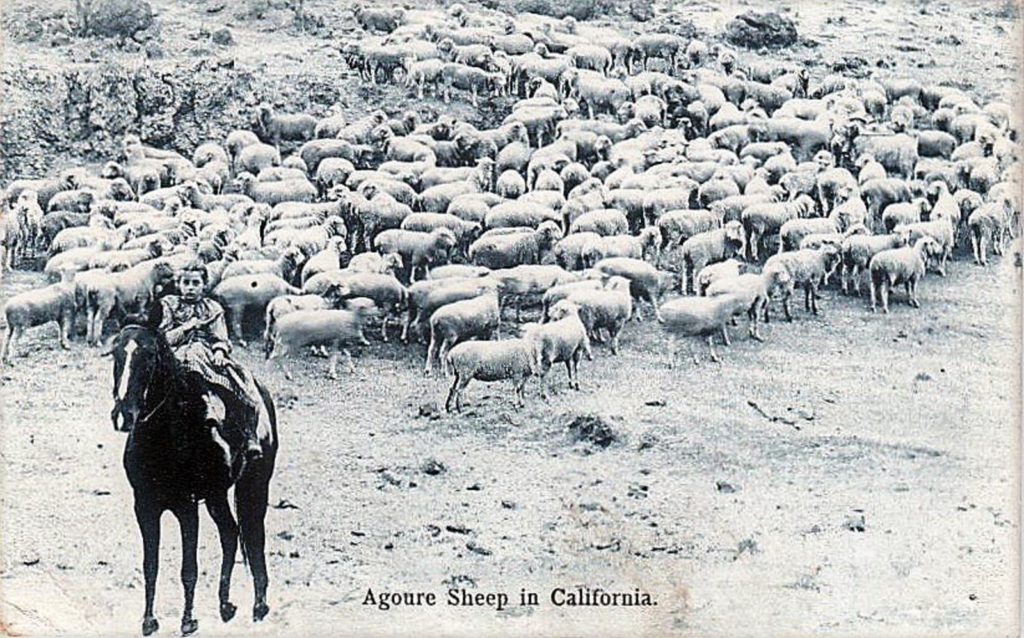

This is the story of an early Ventura County sheep rancher. His remarkable tale has been overlooked and almost lost over time. With hard work, he built a thriving ranch with the biggest sheep herd in California. His untimely death by poisoning led to his family being victimized by a relentless legal predator who tried for eight years to take a piece of the valuable estate. Only a few details were commonly known about the man whose name lives on today in the communities of Agoura and Agoura Hills.

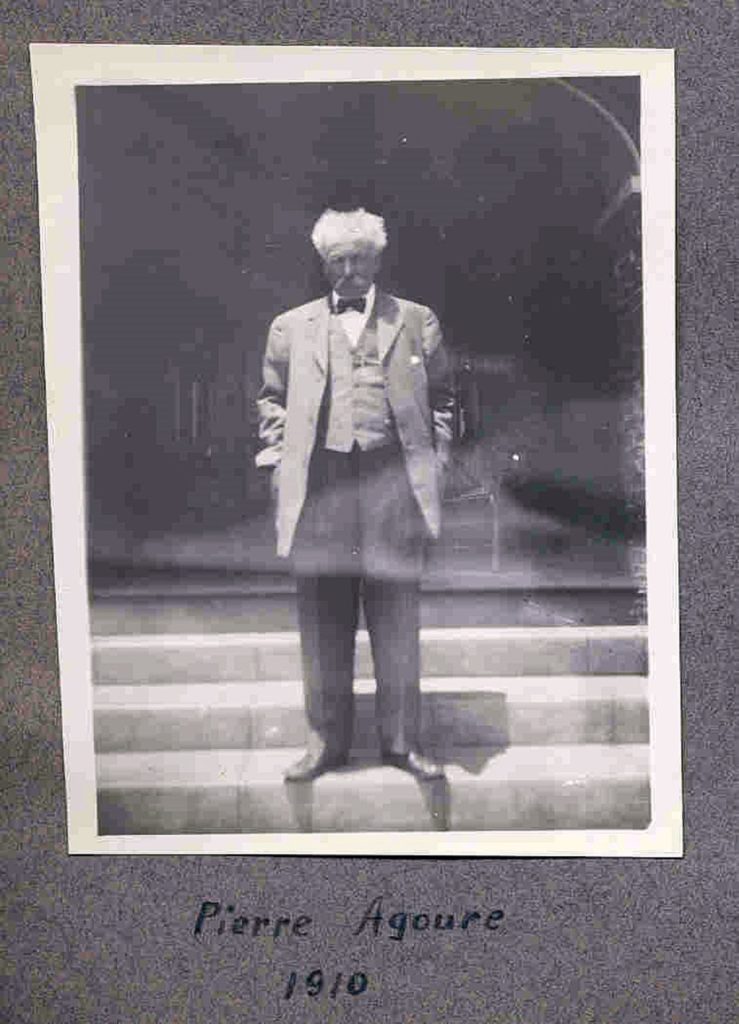

Pierre Agoure was born on May 15, 1853, to a Basque family in the Pyrenees in southern France. He was the second son of Francisco Agoure, a prosperous farmer and stockman. Pierre was one of seven children raised on the family farm and received a public-school education.

By 1870, when Pierre turned 17, economic and political factors began to push many Basques out of Europe. France had declared war on Prussia. The year-long conflict presented a real threat to Pierre of being conscripted into the Army. Also, there was no available land for younger sons to inherit. Second sons like Pierre had few options other than to enter the priesthood.

Pierre found the promise of prosperity in California more alluring than religious life. The teenager stowed away on a ship bound for California. Only Pierre’s older brother remained in France. Of his other five siblings, four eventually moved to Southern California and one to Wyoming.

The voyage took six arduous months. Quickly discovered, the teenage stowaway was put to work. The trip required circumnavigating the treacherous waters of Cape Horn around the tip of South America. Pierre arrived in San Francisco in August 1871. Two months later he came to Los Angeles, landing at San Pedro.

Arrives In the Middle of Mob Violence

Pierre made his way to the pueblo plaza where Olvera Street and Union Station stand today. Los Angeles was a violent city of fewer than 6,000 people and mob justice was commonplace. In October 1871, the teenage immigrant stumbled into one of the most appalling examples of lawlessness in city history.

More than half of the city’s 172 Chinese residents lived along an unpaved alley just off the plaza. The area had become an infamous vice district with gambling, saloons, and brothels. For several years, the Los Angeles News and The Los Angeles Star had been running editorials condemning Chinese immigration and attacking the Chinese as inferior and immoral.

Tensions in the community were high due to a feud between two rival groups over the kidnapping of young women. There was a shootout between several Chinese men in the alley. A city police officer and his 15-year-old brother responded and were wounded. A citizen who attempted to help the officer was killed. An angry mob of 500 people rounded up Chinese men and boys and hanged them on several makeshift gallows. The next morning, 17 bodies were laid out in a nearby yard. According to Pierre’s great-grandson, Pat Nolan, the frightened teenager, who spoke no English, wasn’t certain if the mob hostility was directed towards all foreigners. He was only reassured when he met people speaking the Basque language.

Pierre was hired as a ranch hand by a Frenchman, pioneer rancher Bertrand Riviere, whose land sprawled from present-day South Los Angeles across Western Avenue and into Baldwin Hills. Pierre was paid $20 a month to watch over grazing sheep and to take on the unpleasant jobs such as castrating the animals. He later made $25 a month working on Riviere’s 60-acre dairy farm on Western Avenue. Pierre saved his money and in 1873 bought 400 head of sheep and herded them on the Newhall Ranch (in the Valencia area.) Over the years he gradually acquired more land and sheep. By 1878 he was able to buy the 60 acres on Western Avenue where he had worked for Riviere as a ranch hand.

As his savings grew, Pierre began looking for a partner. He courted Kate Smith, who lived on a ranch 40 miles away. They married in January 1883 and made their home at 723 South Olive Street in Los Angeles. They had six children, five daughters and one son:Juliette, Angele, Bijou, Beatrice, Lester, and Vivian. Pierre became a naturalized citizen in 1890. The U.S. Census of the same year shows the family in their Olive Street home with the children ranging in age from 5 to 15.

California’s Era of Wool

Pierre was building his fortune with sheep at an ideal time. The decade of 1870-1880 became known as California’s Era of Wool. Sheep had become the livestock of choice, as disease and drought had decimated the cattle population in the state. The number of cattle in Ventura County fell to just over 10,000 while the number of sheep peaked at 148,000. By 1880 almost 17 million pounds of wool were produced in California.

Pierre regularly added sheep to his herds and at one time purchased 12,000 sheep from Thomas R. Bard. Robert Cleland, in his book The Cattle on a Thousand Hills, noted sheep farming was not without its challenges. The winter of 1876-77 was abnormally dry. Ranges turned to barren wastes, water sources dried up, and sheep died in “appalling numbers.” On Rancho Los Posas in Ventura County, Bard and his herders “slaughtered 60,000 lambs as fast as they were born.” Pierre lost about 8,000 of his sheep in the dry year of 1898.

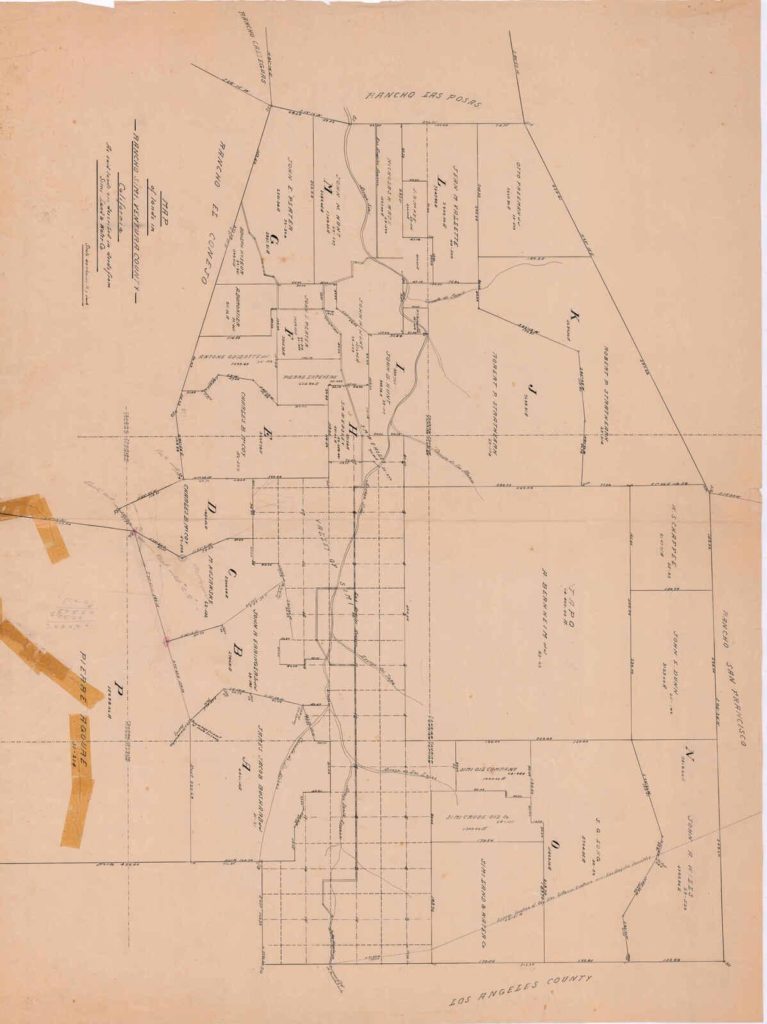

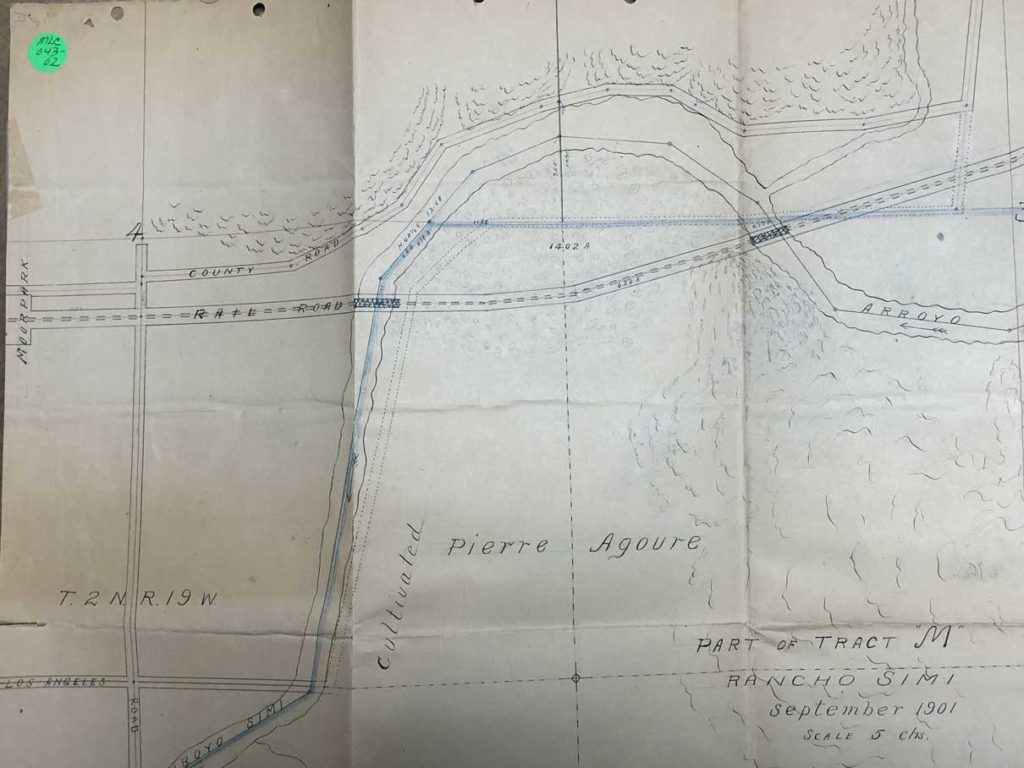

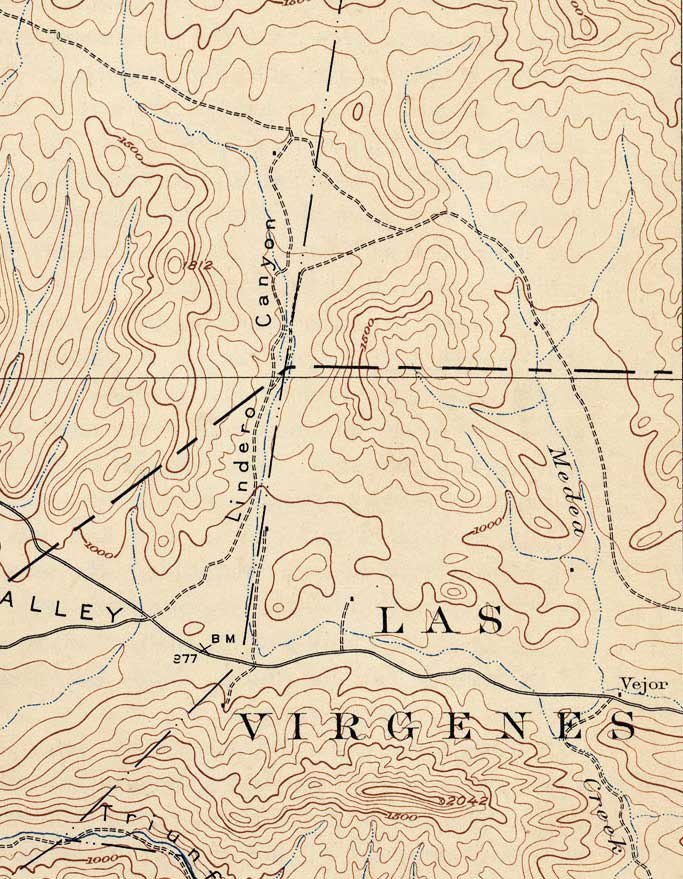

He persevered, later combining cattle raising with sheep and continued to purchase land. By 1906, he owned 16,880 acres of Conejo Valley land, including a portion of Rancho Simi and stretching west into Rancho Las Vírgenes. This included a 1,500-acre ranch near Moorpark and 380 acres near Calabasas.

In addition to his family residence in Los Angeles, Pierre owned the 60-acre ranch on Western Avenue. In 1912, the Los Angeles Times referred to him as “one of Southern California’s millionaire ranch men.”

Pierre spent most of his time on the ranch while his family remained in Los Angeles, where Kate believed the children would receive a better education. Kate and the children visited most weekends at the ranch. Daughter Bijou later recalled getting up at dawn and arriving at the ranch just before sundown.

The Los Angeles French Community

Los Angeles had a robust French community in the late 19th century. The French were the fastest-growing immigrant population in Los Angeles in 1860. Most settled east and southeast of the old pueblo plaza. The Agoures were devout Catholics. They were members of the Cathedral of Los Angeles and supported church charities. In October 1892, the Times reported that five-year-old Angele, who they dubbed the “baby violinist,” played several selections at a week-long fundraiser put on by “the Catholic ladies of this city” to benefit orphans. The Times said Angele showed great ability and “promise of wonderful proficiency with a little more growth and practice.” Juliette’s 13th birthday party in 1896 made the social pages as did Kate’s hosting of a hay-ride party to a Santa Monica canyon luncheon in honor of a friend who had returned from the West Indies.

The Agoures were active in the community’s 1904 celebration of Bastille Day, the French national holiday commemorating the 1789 fall of the Bastille prison. Three daughters participated in an elaborate musical and literary spectacular. Young women appeared in costume representing countries, states, and provinces of France. Juliette represented France, Bijou appeared as America, and Beatrice as the French province of Alsace-Lorraine. In 1905 the children performed in two benefit performances of the comic opera Princess Phosa. The cast, composed almost entirely of amateurs, featured 117 adults and 260 children. Angele, Bijou, and Juliette practiced for six weeks and performed as part of a double octet. A vocal octet is a performance of a choir singing eight separate parts.

Life in Los Angeles was not without its challenges. In 1897, a neighbor named Barbara Wallace filed a $26,000 damage suit claiming the Agoure’s “ferocious, vicious and mischievous” dog jumped on her as she walked past their Olive Street house. The dog knocked her down and broke her leg. The woman claimed she was hospitalized for 23 weeks and remained crippled for life. A year later the case was still being litigated and there is no evidence in the newspapers that it was ever settled.

In 1901, Kate appeared before the Los Angeles City Council to object to “having dead dogs, defunct cats, frogs and oil in the cellar.” With her sister Julia by her side, Kate described how heavy rains had burst a 32-inch cement storm drain under her house and forced “oil and all sorts of dead animals” into her cellar. According to the Times, Kate did “not mind the trout so much but the oil and cats are beyond endurance.” The city quickly agreed to repair the damage.

A Bank for Farmers and Ranchers

Turn of the century Ventura County was the “agricultural frontier.” The 1890 Census shows the county had a population of just over 10,000. There were 764 farms. Pierre became a major investor in a bank vital to the county’s farmers and ranchers. French immigrant Achille Levy had started a business in Hueneme as an agricultural commodities broker. He would pay farmers for their crops and take them to market for sale. Levy became a banker when his customers asked him to hold on to the proceeds of their sales for safekeeping. Through the Bank of A. Levy, he put the money to work and made loans to ranchers and farmers. The bank operated in Hueneme until 1898 when the American Beet Sugar plant opened in Oxnard. The huge plant sent processed sugar beets and refined sugar directly to Los Angeles and to the east. Because it bypassed the deep-water port in Hueneme, most of the town’s population moved to Oxnard and Levy’s bank went with them. In 1905, the private bank obtained a state charter. Pierre is shown as a significant investor in the Articles of Incorporation, which are preserved at the Museum of Ventura County. Pierre purchased 20 shares in the bank. His $2,000 investment would be worth over $67,000 today.

Life on the Armaga Ranch

The crown jewel of Pierre’s ranching empire was his 15,000-acre ranch in Ventura County. While no trace of it remains today, the ranch, called “Armaga,” was said to be “eight miles from Calabasas on the county road leading to San Francisco.” In a 2020 article for the Oak Park High School newspaper, student Shoshana Medved found a description placing the Armaga ranch house “in Ventura County, two miles [north] from the land” of Rancho Las Virgines.” Her evidence suggests the ranch house may have been near the high school in the Medea Creek area of Oak Park.

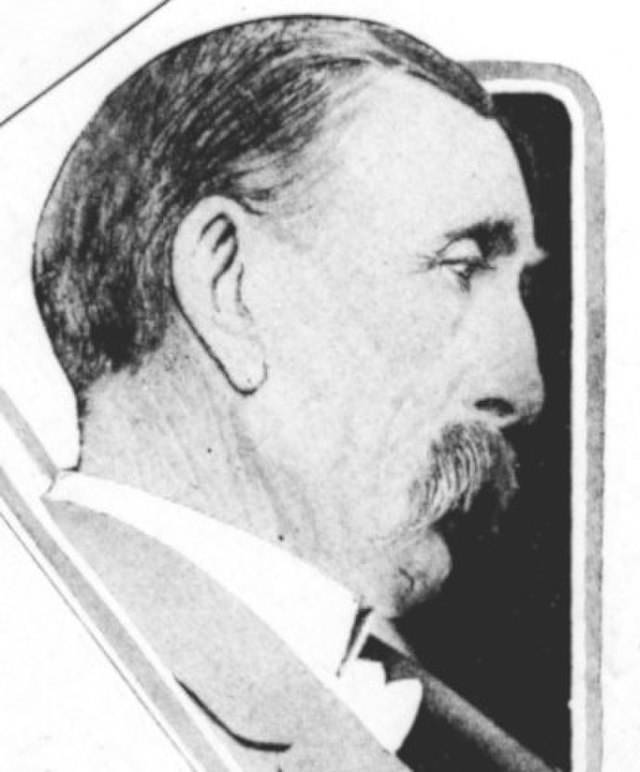

The Times wrote about the ranch in 1912 and described the “undulating hills, grassy slopes, rich valleys and springs of water, the whole surrounded by the rugged peaks of the coastal range. Giant California live oaks and black evergreen oaks of enormous size dot the ranch as far as the eye can see.” Reporter Marshall Taylor appeared equally impressed by the rancher who raised “sheep, cattle, horses, pigs, hay and grain.” He said Pierre “commands instant respect” and described him as “rough in appearance…with his curly white locks, ruddy complexion, and genial countenance, he closely resembles the late Mark Twain.”

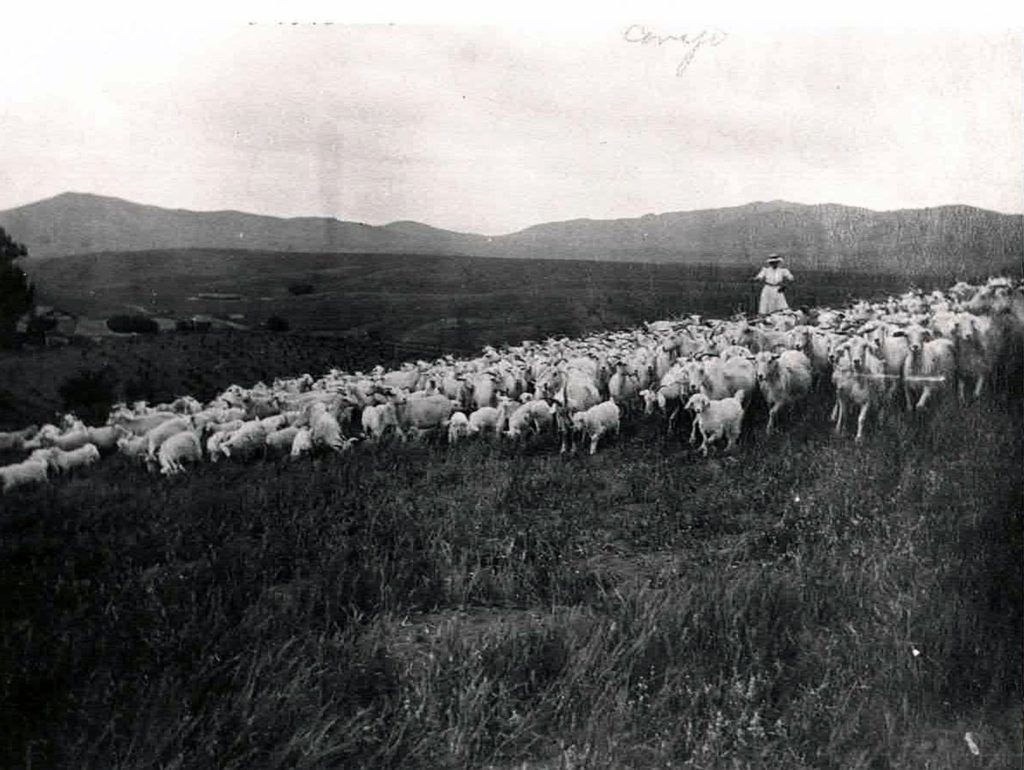

Taylor said Pierre’s “one great boast is that in his earlier days he used to mend his clothes with wire.” He said the ranch is “not a show place, but a typical example of what grit and determination can do in this land of plenty and perpetual summer.” Pierre, with his son and a few ranch hands, had put up “forty miles of wire fencing…entailing the cutting and hauling of thousands of posts; gates, corrals and immense barns and farmhouses.” By this time, Pierre’s sheep herds outnumbered every other herder in the state. It was estimated he had as many at 25,000 animals. He brought in shepherds from the French Pyrenees to tend the flocks. Basque immigrants dominated the sheep herding industry in California. A survey of Ventura County ranchers found only one native American sheepherder, the rest were Basque or Portuguese. One man at the ranch held the record for hand shearing 20 sheep in one hour. Forty 350-pound sacks of wool were clipped annually. In 1911, 1,000 tons of hay were cut, and 5,000 115-pound sacks of wheat were harvested at Armaga.

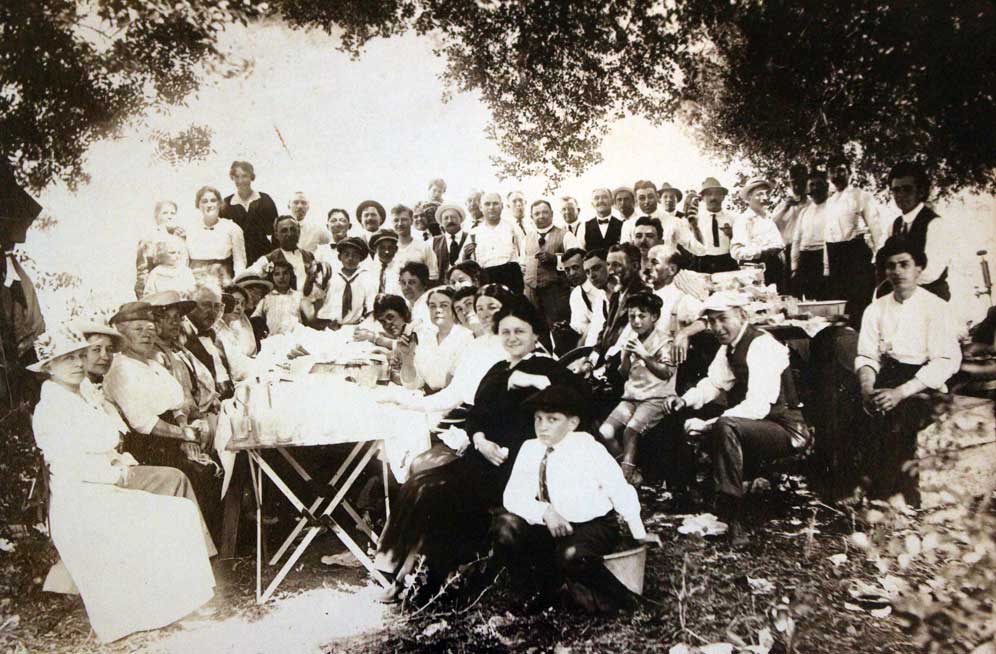

Pierre and Kate held an annual New Year’s Day fiesta on the ranch for all the hands. Trips to the Ventura County ranch were considered a treat for his Los Angeles-based children. In 1906, the Times reported daughters Juliette, Angele, and Bijou were entertaining eight friends on a two-week hunting trip on the ranch, chaperoned by Pierre. J. M. Guinn in his book History of California and an Extended History of Its Southern Coast Counties, describes Pierre’s politics as “true-blue Republican, and although never desirous of personal recognition has nevertheless given time and energy to the advancement of the principles he endorses. He is a worthy and esteemed citizen in every particular…appreciated for the high qualities of character he has displayed.”

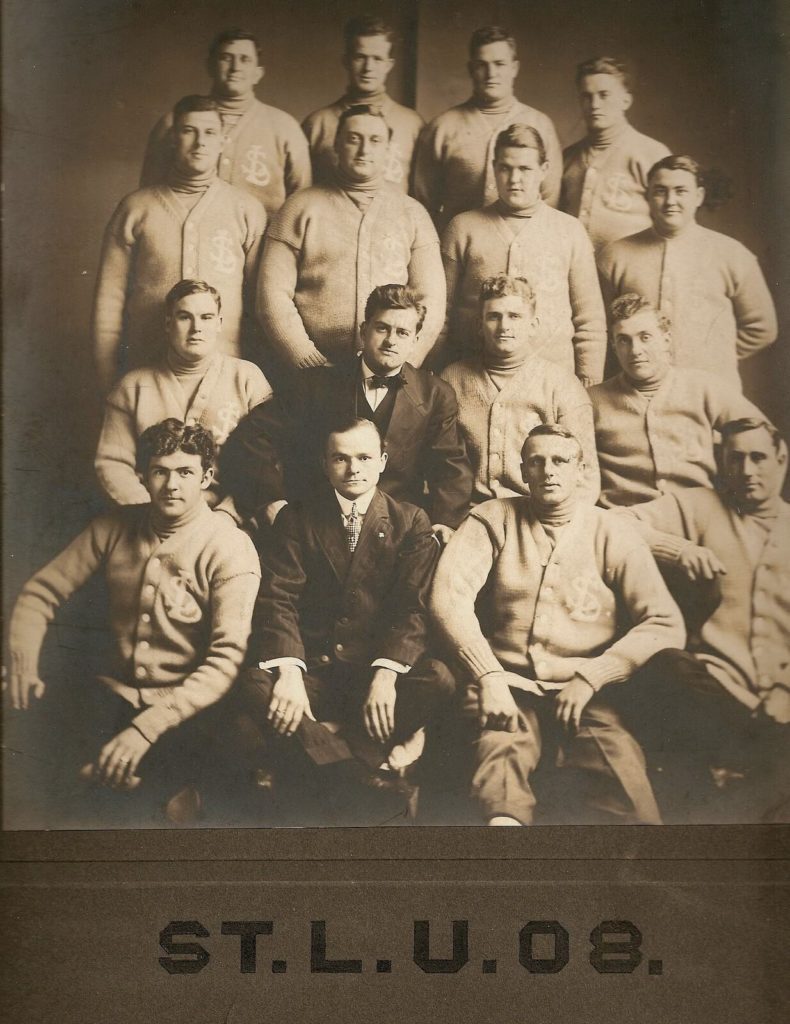

In May of 1906, Pierre’s oldest daughter Juliette married Leo de Celes in El Paso, Texas. The Times noted the marriage united “two of the old pioneer families of the Southland.” Besides his prominent family background, de Celes was a college graduate and “gifted musically.” He sang old Spanish songs in actress Virginia Calhoun’s theatrical adaptation of Helen Hunt Jackson’s immensely popular 1884 novel Ramona.

By 1909 the family had left their Olive Street home and moved to 3955 Western Avenue, very near Western Avenue and Martin Luther King Boulevard today. Family members recall the daughters were not thrilled with the move to Western Avenue, which at the time was on the outskirts of the city, two blocks from the end of the trolley line. They feared boyfriends would not be willing to walk through the dust and mud to visit.

Property disputes were not uncommon. In 1910 Pierre faced neighbor A. D. Morrison in court. He contended he owned a 15-foot-wide road through Morrison’s property leading to his Ventura County ranch. Despite Morrison’s counter claims, Pierre insisted he had held the right of way and easement for more than 20 years. He asked the court for an injunction to prevent Morrison from blocking access to the road.

Accidental Death by Poisoning

The family’s life took a sudden turn when Pierre died on November 29, 1912, at age 59. The death certificate, signed by Los Angeles County Coroner Calvin Hartwell, gave the cause of death as “accidentally taking formaldehyde.” The accidental death determination was accepted, and there is no evidence of any further investigation. It was not unusual that formaldehyde was present at the ranch. In the 1900s, in addition to some agricultural uses, formaldehyde was diluted to create formalin which was used to prevent hoof diseases in cattle and sheep. Formalin belongs to that rare group of poisons which can produce death suddenly when swallowed.

The Strange Story of John Lapique

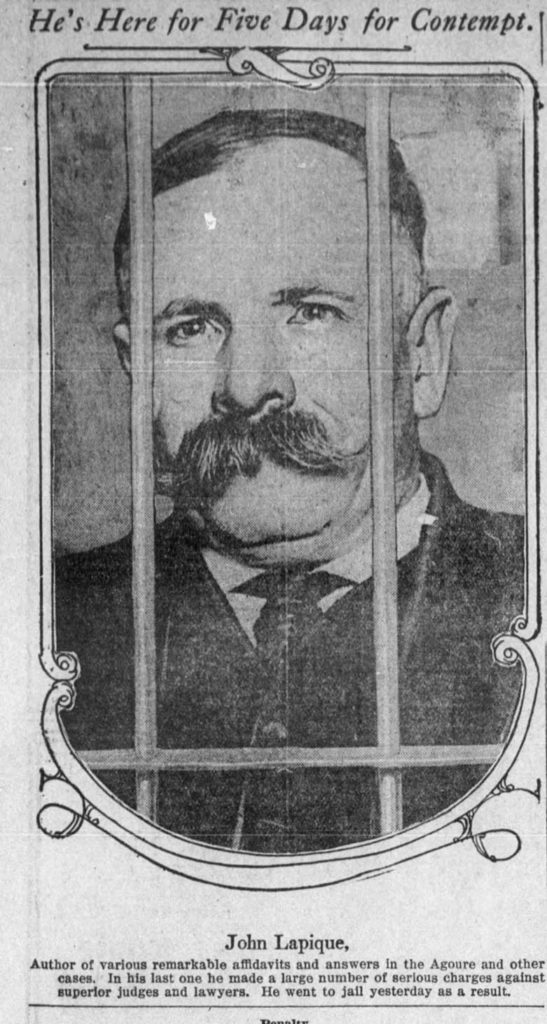

Less than a month after Pierre’s death, a man named John Lapique filed a petition that claimed Kate was unfit to administer the estate. Lapique may be one of the most unusual figures in Southern California legal history. The Times described him as “a Frenchman who buys up claims against old French and Spanish estates, has them assigned to him and then sues. He has been universally unsuccessful and has apparently come to believe all the courts are against him. He is not a lawyer.”

Lapique first appeared in San Francisco newspapers in 1895 when he was accused of swindling a man out of $10,000 in cash and property. Later that year he was convicted of embezzlement for taking advantage of a critically ill and mentally incompetent man by convincing him to deed over all his property. Lapique was held in prison until early 1898 when State Supreme Court reversed his conviction.

In 1899 Lapique was sentenced to nine years in prison after he was convicted of forging a promissory note. He would spend the next four years appealing his case from behind bars. The State Supreme Court granted a new trial, citing insufficient evidence and erroneous rulings. The case was never retried. After getting out of jail in 1904, Lapique filed a $650,000 suit against 42 attorneys and prominent people. He included nearly everyone who had any connection to the many proceedings against him. His lawsuit was dismissed in the fall, but he refiled it a year later. The second suit stalled when the records were destroyed in the 1906 San Francisco earthquake and fire. It would finally be dismissed 11 years later due to lack of prosecution.

The earthquake apparently prompted Lapique to move his “law and collection agency” to Los Angeles. The newspapers referred to him as the “refugee attorney.” Despite making “all kinds of charges,” he failed to oust the executors of the estate of an elderly Los Angeles couple.

Next, in 1907, he targeted the estate of Joseph Toussau. He sought to have Toussau’s young widow declared mentally incompetent and unfit to manage the estate. When the widow’s attorney brought up Lapique’s checkered past in court, he responded by demanding the attorney and other members of his firm be disbarred. Lapique told the judge that their comments had caused the Santa Ana Register to publish an article on him that was “not at all flattering to his character.” Lapique not only failed to prove the widow’s incompetence, but his call for sanctions against the attorneys, which “caused no end of laughter” at the courthouse, was denied by the judge.

Lapique wound up in jail again in 1908 when he was unable to post bond after he was charged with selling property to which he had no title. Representing himself, Lapique displayed a sales contract which he claimed was signed by the owners. Despite repeated, time-consuming objections as well as the testimony of a handwriting expert, Lapique was convicted and sentenced to ten years in prison. From jail, Lapique filed a 100-page appeal. Over the next year, he would appear in court in handcuffs and quibble over technicalities and fine points of law. Weary appeals court judges finally concluded the allegations against Lapique were not proven and he was granted a new trial, which was never pursued. Once again, Lapique filed suit, claiming false imprisonment and named 39 defendants connected with the trial including judges.

In 1910, Lapique inserted himself into an estate that had been settled for 16 years. When French baker Marie Begon died in 1894, her granddaughter was made executor of the estate. Lapique filed suit on behalf of Begon’s estranged husband. He challenged the existence of a valid will and accused the granddaughter of mismanagement. Lapique contended the husband should be entitled to all community property. During the two-year trial, the will was located, and it was revealed the unhappy couple had separated by mutual consent and divided their property between them. The suit was thrown out in 1912.

Lapique Targets the Agoure Estate

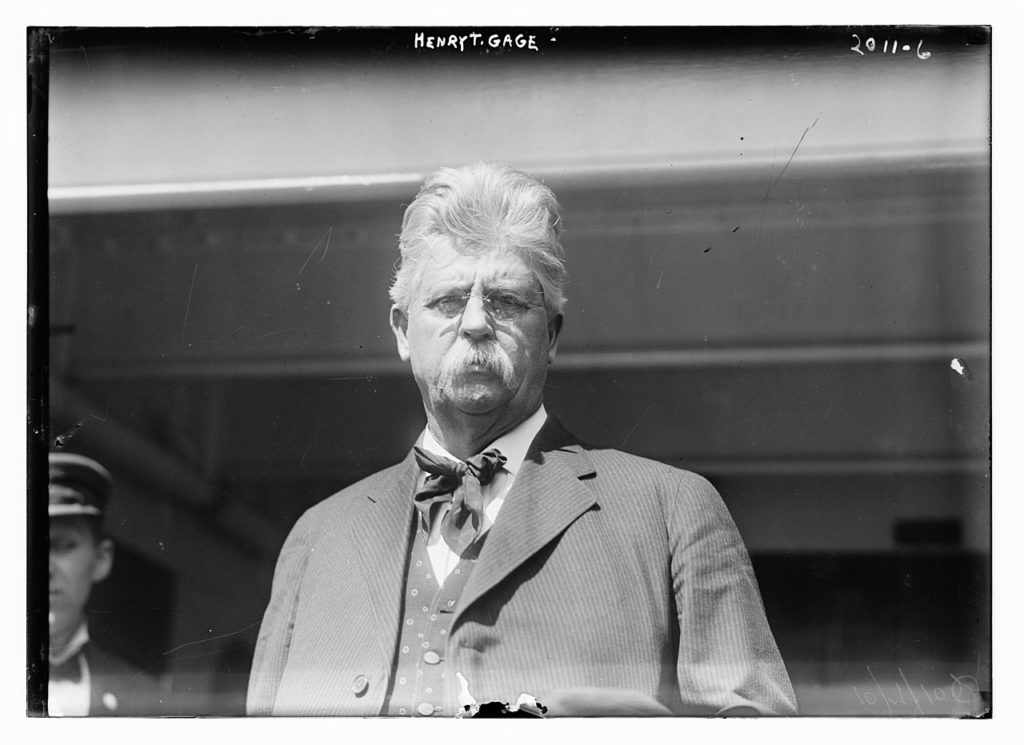

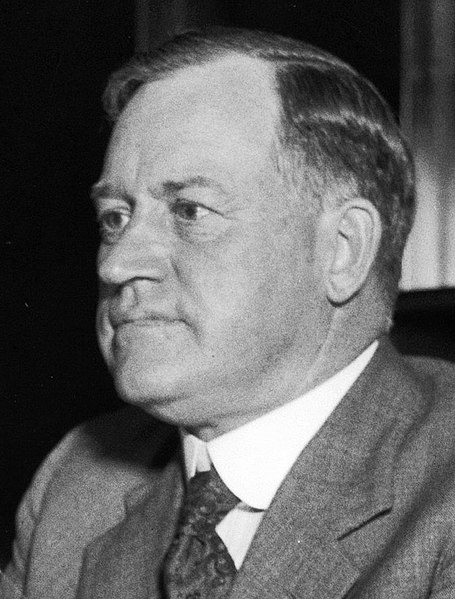

Pierre’s estate was substantial. The ranches, other properties, cash, livestock, as well as large quantities of grain and hay were valued at $500,000 dollars, almost $15 million today. As a wealthy woman, Kate was able to hire two of the best law firms, O’Melveny, Stevens & Millikin and Gage & Foley. Lapique pressed his attack on Kate’s competence in early January 1913, when he filed a petition that her lawyers “characterized as a scurrilous attack.” He attempted to introduce that Pierre’s death was not the result of an accident. That drew an immediate objection from Kate’s attorney Henry T. Gage, a former governor of California. The judge agreed with Gage that the only part of Lapique’s petition worth considering was his contention that he was a creditor of the estate. The judge ruled there was no reason to disqualify Kate and she was appointed executor.

Within two weeks, Lapique filed suit seeking $1 million in damages from Kate and her children. He now claimed Pierre’s death had ended a partnership between the two men to acquire property worth $1 million. Lapique also asserted that Pierre’s death was caused by “poison which had been negligently and carelessly left” about the dead man’s house by his family. Three days later, the presiding judge of the Superior Court, Frank R. Willis, dismissed the suit and added, “citizens should not be harassed by legal proceedings instituted by irresponsible persons and that the court should not waste time and incur expense considering such pleadings.” Willis’ decision was sustained by another judge, W. I. Morrison three months later. While he gave Lapique an opening to amend his suit, he added a warning that if he failed to prove his serious charges “he may be prosecuted for libel.”

In September 1914, Lapique sought to have Judge James C. Rives halt the distribution of the estate. He made the sensational charge that the family had “conspired to kill Agoure for two years” and finally “did put him out of the way by administering formaldehyde.” Judge Rivas declared the manner of Pierre’s death was not on trial in probate court and he would only hear testimony on the property involved in the case. Lapique presented what he claimed was a partnership agreement and wanted Kate to be compelled to pay him $27,000 for his services.

On the stand, Kate declared the agreement was a forgery. “He (Lapique) had nothing to do with the estate at all. That’s manufactured, all that stuff.” “Have you filed an accounting, Mrs. Agoure?” asked Lapique. “I don’t have to answer him, do I?” she appealed to the court. Judge Rives told her to answer. “Will you state whether you have filed any account in the estate of Agoure?” repeated Lapique. “It’s none of your business,” Kate snapped. “Mrs. Agoure, we are trying this case,” began the judge. “We will get along better if you confine yourself to the questions.” Later, he said if it were not for the fact that she was an elderly woman, he would fine her for contempt. “I will pay a fine,” Kate retorted. “I can’t stand that man.”

Lapique Accuses Judges of Bias

In October, Judge Rivas decided Lapique’s claims were invalid and ordered a partial distribution of $350,000 to Kate and the children. A month later Lapique sought to reverse the order. In a sensational affidavit he repeated his assertion that Pierre had been murdered. He also accused 13 superior court judges of bias and prejudice and demanded the case be transferred to another court. Additionally, he accused several county officials, including the county clerk and district attorney, of prejudice against him.

Kate’s attorney, W.I. Foley, asked Judge Rives to confer with the other superior court judges on a contempt charge against Lapique. Judge Rives referred the estate claims to Judge Frederick W. Houser and the contempt proceedings to presiding judge J. Perry Wood. Rives had a sharp parting warning for Lapique. He said the court would deal “justly, fairly and manfully” with him, but would teach him his reckless behavior could not continue. “I have to say to you Mr. Lapique, that you have just about reached the end of this kind of charges. Certainly, that affidavit is not to go unnoticed or unchallenged by the court.”

Convicted of Contempt of Court

In December Judge Wood asked Lapique why he should not be punished for contempt. Lapique said, “I am not an attorney-at-law; whatever I do here is done in good faith. If you don’t think my answer is sufficient, I desire to introduce some evidence, I desire to be heard.” “Be seated,” Judge Wood said, “You will have to be taught that this business of filing affidavits against everybody and everything must stop. This mass of charges you have filed is inflammatory and you are in contempt.” As he was taken to jail, Lapique said, “I will get Judge Wood for this unfair treatment. All I want is a fair deal. I will have him impeached. The next time we meet it will be before the State Senate at Sacramento.”

Judge Wood sentenced Lapique to pay $500 on the contempt charge. He was ordered to remain in county jail until the fine was paid. He would spend 250 days in jail working off the fine at $2 a day. Shortly after the sentencing, Pierre’s son Lester filed a libel suit against Lapique.

Lapique Gets Five Stiff Punches

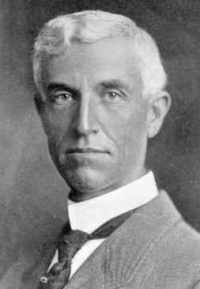

In January 1915, Lapique was brought from his jail cell to oppose the distribution of the estate once again. In addition to his claim of $27,000, Lapique now demanded that a portion of the estate be given to two of Pierre’s relatives in France. He told Judge Houser their claim should be considered before any distribution was made. But pandemonium broke loose when Lapique told the court, “It has not been shown that Kate Agoure is the legal wife of Pierre Agoure.” Not 10 feet away, real estate man Walter Brinkop, the husband of Kate’s daughter Bijou, with “blood boiling…sprang from his chair and ran swiftly to Mr. Lapique.” Brinkop landed “five stiff punches” to Lapique’s head and sent him sprawling on the lawyer’s table.

Kate and her daughters “ran screaming from the courtroom” as two sheriff’s deputies and several spectators dragged the former football player away. “He assaulted the name of a good woman,” shouted Brinkop, breathing hard. Brinkop was taken into custody and Judge Houser gave him the choice of paying a $100 fine or serving 50 days in jail. Family attorney H.W. O’Melveny said, “I will make out a check for the amount now.” Brinkop apologized to Judge Houser but added he could not “suffer a statement such as Mr. Lapique has made” and let it go without objection. He later told a reporter, “At $20 a punch, it was worth it.” As Lapique was taken back to county jail he was heard saying, “it didn’t hurt.” The Times reported Bijou came up “to her stalwart husband, grave concern in her eyes, but a sense of triumph in them for the punishment of a man whose scandalous charges have been a source of anguish to her mother.” When court resumed later in the day, the judge ruled the French heirs claim to the estate was too remote, especially since Pierre had a brother and sister living in Southern California. O’Melveny argued that the $150,000 set aside was more than sufficient to deal with any claims against the estate. Lapique’s motion was denied.

The Attempt to “Get Judge Wood”

Lapique followed through on his threat to “get Judge Wood.” In April 1915, Lapique petitioned the State Legislature to impeach Judge Wood as well as Judge John M. York who had replaced Wood as presiding judge a month earlier. The petition accused the respected jurists of misconduct in office. While Wood and York had no public comment, other superior court judges called it a “farce and unworthy of the attention of the Assembly or anyone else.” Assembly Speaker Clement C. Young said while he found the charges “frivolous and farcical,” he would pass them on to State Attorney General Ulysses S. Webb for further investigation. Young said he could not refuse to recognize the constitutional right of any citizen to address the legislature for redress of grievance. He added he expected the Assembly judiciary committee would dismiss the charges. Before the committee acted, Lapique filed a second misconduct complaint, naming two justices of the State Supreme Court, one associate justice of the Third District Court of Appeals, and eleven judges of the Los Angeles Superior Court. In May the Assembly judiciary committee called the complaint “unworthy of serious consideration” and threw it out.

At the same time, Lapique lost in the State Supreme Court. He had appealed Judge Willis’ 1913 dismissal of his $1 million damage suit alleging Pierre’s death was caused by the family’s negligence. The court found it “utterly without foundation” and refused to take up the appeal. The opinion stated that “citizens should not be harassed by legal proceedings instituted by irresponsible persons.” The justices added, “Nothing quite so preposterous has, to our knowledge, ever been presented in any court.”

Criminal Libel Suit Against Lapique Begins

Hearings had begun in the criminal libel suit Lester had filed against Lapique for accusing him of murdering his father. Still a county jail inmate, Lapique promised police court Judge R. P. Chesebro that he would make the case historic as the “most thoroughly fought of any case ever” in the city courts. More than 200 witnesses were called including former governor Gage, all the judges of the superior court, 20 prominent attorneys and many leading physicians. The Times decried the $5,000 worth of time wasted in one day as prominent citizens waited to testify.

Lapique made excessive demands. He wanted the Assistant Surgeon of the Los Angeles Central Receiving Hospital to bring the records of every case he had treated over the preceding two years. Many of Lapique’s subpoenas were rejected by Judge Chesebro who refused to allow witnesses to testify about “plots” against Lapique.

Lapique sat at a table “so burdened with documents that a janitor, at the close of the session, thought them refuse and started to cart them away in a garbage can, getting to the door with several dozen before he could be stopped.”

On July 2, 1915, after deliberating for just five minutes, the jury found Lapique guilty of criminal libel. Lapique boasted at his sentencing that in 12 years, there had only been two months when he didn’t have some action pending the superior courts. He was sentenced to one year in county jail. He would begin serving his sentence in October, after completing his 250-day sentence for contempt. After serving his two jail terms, Lapique filed a $175,000 suit against Kate for false imprisonment. After a series of legal defeats, his suit was dismissed by the federal court of appeals in January 1921. Kate died the next year.

Family Begins to Sell Off the Ranch

After Pierre’s death, his son Lester managed the Armaga ranch. It even appeared in the movies. In 1922 the western “Man to Man” was filmed there and featured some of the ranch cattle as “extras.” Eventually the family began to sell off pieces of the ranch. In 1924, in one of the year’s biggest farmland deals, 15,098-acres sold to a group of Los Angeles investors represented by realtor Joe Toplitzky. The sale price was not disclosed but the Los Angeles Herald estimated the land sold for more than $1 million. The first subdivided tracts of 10 ranches became known as Independence Acres.

Since the ranch was first developed, Calabasas had been the postal center for the district. Residents petitioned for a closer post office and 10 names were submitted to the U.S. Postmaster. Agoure, the last and shortest name on the list, was selected. The “e” on Pierre’s name was changed to an “a” to match the pronunciation of Agoure. Since 1928, Pierre’s name has lived on in the communities of Agoura and Agoura Hills.

In 1927, Publisher William Randolph Hearst bought 15,000 acres of ranch land stretching from Chatsworth Lake to Newbury Park, including Rancho Simi Tract P, which was owned by Pierre. The Hearst Corporation sold the land to the Albertson Company in 1943. In 1954, Albertson sold 5,000 acres to NBC radio stars Jim and Marian Jordan (Fibber McGee and Molly). The Jordans later sold some of the land to entertainer Bob Hope and celebrity attorney Joe Ross. The property eventually became the unincorporated Ventura County community of Oak Park in 1966. The last 1,465 acres of land owned by the Agoure family were sold by Pierre’s daughter Angele in 1963. The ‘baby violinist” was 78 years old and represented in the $1.1 million transaction by her son Peter Vail.

Lapique Goes After Leonis Estate

In May 1919, Lapique inserted himself into the estate Miguel E. C. de Leonis which had been the subject of protracted legal disputes since his death in 1889. A Basque sheepherder, Leonis acquired land in what is now the West Hills portion of Los Angeles in the 1850’s. He aggressively added acres by bullying, suing, or buying up homesteaders. He ultimately controlled land from the west end of the San Fernando Valley into part of Ventura County. He died after falling and being run over by his wagon while returning from court in Los Angeles.

Lapique claimed to have a judgement against the half-million-dollar estate and began badgering Los Angeles County Clerk Harry Lelande to sign over a deed to some of the land. Lelande was at first reluctant, but after Lapique threatened suit, he signed. The Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors caught wind of the unauthorized transaction and forced Lelande to resign.

In August, Lapique was behind bars again, unable to post bond after being indicted by the grand jury for filing three suspect deeds with the county clerk. By obtaining repeated continuances he avoided entering a plea for 18 months. In February 1921 the county jail’s “oldest inhabitant” was granted his 47th continuance. Two years of fighting his case on technicalities finally paid off when the indictment against him was dismissed and he was released from jail.

In 1922 Lapique filed suit against judges, attorneys, and prominent citizens, asking for $255,000 in damages for false imprisonment. One of the named defendants was Chief Justice of the State Supreme Court C.J. Wilbur. The high court would dismiss all his claims in 1923, calling his appeals frivolous. In ten years, Lapique had filed and lost 52 cases seeking title to the Leonis estate. In February 1928, the U.S. Supreme Court dismissed his last appeal after learning Lapique had died, unnoticed, sometime in 1927. When Leonis’ widow died, her son, Juan Menendez moved into the Leonis adobe with his family. Menendez sold the property to the Agoure family in 1922. They lost the property to foreclosure in 1931. The Leonis adobe still stands in Calabasas.

Great grandson Nolan admits history may have overlooked Pierre’s contribution to the growth of Ventura County. One reason could be that the land he developed, bordering two counties, may have been perceived as too far away from the economic centers of Los Angeles and Ventura. A history of the French in Oxnard refers to Pierre’s ranch as being in the “outlying area.” As for his legacy, Nolan called Pierre an “upstanding guy” who “never got behind in his taxes,” employed lots of people, and cared about his community. “He was low key, not fancy. He was just a rancher.”

Make History!

Support The Museum of Ventura County!

Membership

Join the Museum and you, your family, and guests will enjoy all the special benefits that make being a member of the Museum of Ventura County so worthwhile.

Support

Your donation will help support our online initiatives, keep exhibitions open and evolving, protect collections, and support education programs.

Bibliography

- “Agoura Hills, California.” Familypedia. Accessed November 14, 2022. https://familypedia.fandom.com/wiki/Agoura_Hills,_California.

- “Boarding Houses and Handball Courts: The Fleeting Story of Los Angeles’ French Town.” KCET. Last modified January 1, 2017. https://www.kcet.org/history-society/boarding-houses-and-handball-courts-the-fleeting-story-of-los-angeles-french-town.

- Citizen-News (Hollywood, CA). “Historic Simi Site, Agoure Ranch, Sold.” September 12, 1963.

- Cleland, Robert G. The Cattle on a Thousand Hills: Southern California, 1850-1880. San Marino, California: Huntington Library Publication, 1951.

- The Evening Bee (Sacramento, CA). “John T. Adair.” July 3, 1895.

- The Evening Mail (Stockton, CA). “Wins Case as His Own Lawyer.” May 26, 1909.

- “Farming With Formaldehyde.” Mercy For Animals. Last modified April 6, 2020. https://mercyforanimals.org/blog/farming-with-formaldehyde/.

- “Forgotten Los Angeles History: The Chinese Massacre of 1871.” Los Angeles Public Library. Accessed November 14, 2022. https://www.lapl.org/collections-resources/blogs/lapl/chinese-massacre-1871.

- “Formaldehyde.” Illinois Department of Public Health. Accessed November 14, 2022. https://www.idph.state.il.us/cancer/factsheets/formaldehyde.htm.

- “French in LA.” LA Walking Tours. Accessed November 14, 2022. https://www.lawalkingtours.com/french-in-la.

- Grise, Carmen. History of the French in Oxnard and vicinity scrapbook. 1993.

- Guinn, James M. A History of California and an Extended History of Its Southern Coast Counties: Also Containing Biographies of Well-known Citizens of the Past and Present. Los Angeles: Historic Record Company, 1907.

- “Henry Tifft Gage.” Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia. Last modified September 5, 2022. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Henry_Gage.

- “History of the French Community in L.A.” SkyscraperCity Forum. Last modified May 8, 2007. https://www.skyscrapercity.com/threads/history-of-the-french-community-in-l-a.367672/.

- Independent (Long Beach, CA). “Agoura Ancestor.” August 21, 1970.

- It’s Been a Great 100 Years, Bank of A. Levy. 1882-1982. Oxnard, CA: Bank of A. Levy, 1982.

- Las Virgenes Enterprise (Woodland Hills, CA). “The Name Agoura.” May 22, 1969.

- Los Angeles Daily Star. “Murder! Terrible Outrages!” October 25, 1871.

- Los Angeles Evening Express. “$1,000,000 Is Paid for Ranch Property.” October 4, 1924.

- Los Angeles Evening Express. “$175,000 Claim for Jailing Is Dismissed.” January 12, 1921.

- Los Angeles Evening Express. “Gets Own Case to Its 47th Continuance In Court.” March 1, 1921.

- Los Angeles Evening Express. “Lapique In Court Gets Delay of One Month.” August 28, 1919.

- Los Angeles Express. “Judge Flayed by Plaintiff in Court.” November 12, 1914.

- Los Angeles Express. “Lapique Fine $500 On Contempt Charge.” December 15, 1914.

- Los Angeles Express. “Lapique Fined for Contempt.” December 8, 1914.

- Los Angeles Express. “Lapique Found Guilty of Criminal Libel.” July 2, 1915.

- Los Angeles Express. “Lapique Granted Time for Supplemental Bill.” December 28, 1908.

- Los Angeles Express. “Lapique Held to Superior Court.” May 5, 1908.

- Los Angeles Express. “Lapique Is Defeated in Agoure Efforts.” January 19, 1915.

- Los Angeles Express. “Lapique Secures Reversal of Court.” May 26, 1909.

- Los Angeles Express. “Lapique To Appear on Contempt Charge.” November 28, 1914.

- Los Angeles Express. “Lapique to Argue His Case at Length.” July 10, 1908.

- Los Angeles Express. “May Be Prosecuted If Charge Unproved.” March 24, 1914.

- Los Angeles Express. “Reflection On Woman Ends in Attack.” January 18, 1915.

- Los Angeles Express. “Walter Brinkop, Dealer in Realty, Strikes John Lapique in Legal Controversy Over Million-Dollar Estate.” January 18, 1915.

- Los Angeles Herald. “A Heavy Claim.” September 29, 1897.

- Los Angeles Herald. “Asks Investigation of Estate’s Condition.” July 31, 1910.

- Los Angeles Herald. “Begon vs. Begon.” November 3, 1893.

- Los Angeles Herald. “Big Cast for Princess Phosa.” May 4, 1905.

- Los Angeles Herald (Los Angeles). “Deaths.” June 12, 1896.

- Los Angeles Herald. “File Suit to Quiet Title to 15,000 Acres of Land.” September 11, 1910.

- Los Angeles Herald. “Freed From Jail, Sues Prosecutors for $50,000.” May 20, 1910.

- Los Angeles Herald. “Gets Ten Years Despite His Ingenious Defense.” August 1, 1908.

- Los Angeles Herald. “Lapique, Still Fighting For His Liberty, Files Appeal.” August 23, 1908.

- Los Angeles Herald. “Makes Own Defense But Is Convicted.” July 12, 1908.

- Los Angeles Herald (Los Angeles). “Report Many Sales of Agoure Pk. Lots.” November 1921.

- Los Angeles Herald. “Sentenced To Prison; Still Fights For Liberty.” October 17, 1908.

- Los Angeles Herald. “Would Reopen Eighteen-Year-Old Will Contest.” September 2, 1910.

- Los Angeles Record. “County Clerk Lelande Out.” May 13, 1919.

- Los Angeles Record. “Lapique Gets Legal K.O.” January 12, 1921.

- Los Angeles Record. “Lapique Sues Court Officials for $50,000.” May 19, 1910.

- The Los Angeles Times. “A Bad Dog and the Law.” September 29, 1897.

- The Los Angeles Times. “A Birthday Celebration.” December 6, 1896.

- The Los Angeles Times. “A Lot in Dispute.” March 9, 1894.

- The Los Angeles Times. “Agents’ Fees.” February 25, 1898.

- The Los Angeles Times. “Agoure Estate Partial Distribution.” October 11, 1914.

- The Los Angeles Times. “Agoure Hunting Trip.” March 23, 1906.

- The Los Angeles Times. “Bastille Day.” July 14, 1904.

- The Los Angeles Times. “Community Profile: Agoura Hills.” October 11, 1996.

- The Los Angeles Times. “County Clerk Lelande Resigns By Request.” May 13, 1919.

- The Los Angeles Times. “Court Ignores Poison Tale.” September 18, 1914.

- The Los Angeles Times. “Courthouse Notes.” December 20, 1912.

- The Los Angeles Times. “Cowboy and Ranch Life Two Hours from Los Angeles.” January 1, 1912.

- The Los Angeles Times. “Deaths.” November 30, 1912.

- The Los Angeles Times. “Five Punches, Twenty Apiece.” January 19, 1915.

- The Los Angeles Times . “Five Thousand Dollars Wasted Upon Lapique.” July 1, 1915.

- The Los Angeles Times. “Hayride.” August 10, 1899.

- The Los Angeles Times. “His Attack Is Flash in Pan.” January 8, 1913.

- The Los Angeles Times. “Into Court and Then Out Again.” September 21, 1906.

- The Los Angeles Times. “Judge Says Nay.” January 19, 1907.

- The Los Angeles Times. “Judges’ Critic Facing Music.” November 24, 1914.

- The Los Angeles Times. “Lapique Again.” April 22, 1915.

- The Los Angeles Times . “Lapique Case to Be Tried Today.” June 30, 1915.

- The Los Angeles Times. “Lapique Fails in Final Effort on Land Claims.” January 10, 1928.

- The Los Angeles Times . “Lapique Given a Year In Jail.” July 3, 1915.

- The Los Angeles Times . “Lapique Given Coup De Grace.” January 12, 1921.

- The Los Angeles Times . “Lapique Stays In.” October 18, 1919.

- The Los Angeles Times . “Loses Claim While Shut in Jail.” June 17, 1915.

- The Los Angeles Times. “Mister Lapique Now Inside Looking Out.” December 9, 1914.

- The Los Angeles Times. “Mr. and Mrs. De Celes Return.” August 19, 1906.

- The Los Angeles Times. “Neighborhood Spotlight: Agoura Hills.” February 24, 2018.

- The Los Angeles Times . “Now He Wants ‘Em Impeached.” April 10, 1915.

- The Los Angeles Times. “On False Evidence.” July 9, 1919.

- The Los Angeles Times. “Orphans’ Fair.” October 26, 1892.

- The Los Angeles Times. “Romance Unites Pioneer Families.” May 23, 1906.

- The Los Angeles Times. “Storm Pipe.” March 1, 1901.

- The Los Angeles Times. “Supreme Court Dismisses Last of Lapique Suits.” February 25, 1928.

- The Los Angeles Times. “Told to Stop Court Delays.” February 2, 1921.

- The Los Angeles Times. “Wants Right of Road.” September 11, 1910.

- Medved, Shoshana. “Discovering the Forgotten History of OPHS Land.” Talon. Last modified December 17, 2020. https://oakparktalon.org/10572/showcase/discovering-the-forgotten-history-of-ophs-land/.

- “Miguel Leonis.” Accessed November 14, 2022. https://basquesincalifornia.eus/second-period-1849-1960/pioneers/miguel-leonis/.

- Modesto Morning Herald. “Los Angeles County Clerk Asked to Quit.” May 13, 1919.

- The Morning Echo (Bakersfield, CA). “Charges Thrown Out in Impeachment Case.” May 7, 1915.

- “Pierre Agoure.” Find a Grave – Millions of Cemetery Records. Accessed November 14, 2022. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/17763915/pierre-agoure.

- The Record (Los Angeles, CA). “$1,000,000 Suit Ended by Death.” December 10, 1927.

- The Record (Los Angeles, CA). “Million Dollar Suit Dismissed.” January 24, 1913.

- The Sacramento Bee. “Lapique Found Guilty of Libel.” July 2, 1915.

- The Sacramento Bee. “Lapique Sues for $2,000,000.” May 19, 1910.

- The Sacramento Bee. “Report Will Be Made on Impeachments Asked.” April 12, 1915.

- The Sacramento Bee. “Suit Against Lapique Begins.” June 30, 1915.

- The San Francisco Call. “Family Sued for Death.” January 21, 1913.

- The San Francisco Call. “Grants Lapique Another Trial.” June 8, 1902.

- The San Francisco Call. “Grieving Over His Loss.” July 11, 1895.

- The San Francisco Call. “Prisoners Sent to Jail.” October 21, 1900.

- San Francisco Chronicle. “Justice Wilbur And Others Are Accused In Suit.” April 9, 1922.

- The San Francisco Chronicle. “Lapique Wants Heavy Damages.” July 3, 1904.

- The San Francisco Examiner. “Asks For Impeachment of Los Angeles Judges.” April 10, 1915.

- Santa Ana Register. “Lapique Makes Another Move.” January 11, 1907.

- Santa Ana Register. “Lapique Would Have Keech Disbarred.” January 18, 1907.

- Swanson, Mark T., Naval A. Station, and United States. Army. Corps of Engineers. Los Angeles District. Historic Sheep Ranching on San Nicolas Island. 1993.

- “The Toxic Effects of Formaldehyde and Formalin.” PubMed Central (PMC). Last modified February 1. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2124506/.

- “Two Early Basque Towns.” Accessed November 14, 2022. https://basquesincalifornia.eus/second-period-1849-1960/two-early-basque-towns/.

- Ventura County Star-Free Press. “Old Agoura Ranch Land in Big Sale.” September 7, 1963.

- Ventura Daily Democrat. “Pierre Agoure.” December 3, 1912.

- White, Eugene. “California Banking in the Nineteenth Century.” In American Economy Program. New Brunswick, New Jersey: Rutgers University, 1997. Presentation.

- ““As a Native Daughter of California” — Parsing Virginia Calhoun’s Claim on Ramona.” Lewis Center for the Arts. Last modified March 15, 2016. https://arts.princeton.edu/events/parsing-virginia-calhouns-claim-on-ramona/.