by Library Volunteer Andy Ludlum

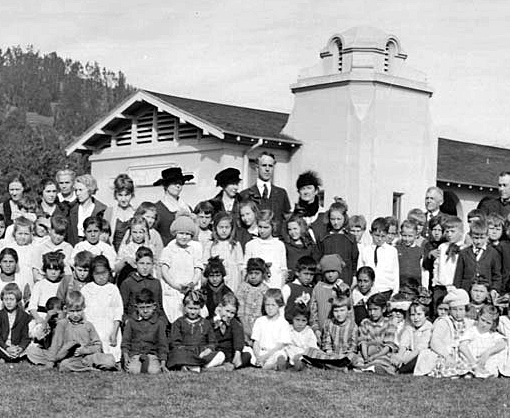

Marjery Misner was described in 1924 by The Los Angeles Times as a “pretty, young teacher.” Near the end of the term, the first-year elementary school teacher in Santa Paula was summoned to the South Grammar School office of the district superintendent, Charles D. Jones. Jones reportedly “raved” at Misner. He said she was an “A-1 teacher, faithful worker, conscientious, and of good character.” But he said her actions two weeks earlier left him with no choice. She could no longer teach in Santa Paula, and he asked for her resignation. What had Misner done to prompt such an arbitrary reaction from Jones? She defied a school board edict – and bobbed her hair. The 29-year-old Misner’s haircut embroiled her colleagues, parents and the school board in a controversy that would make Santa Paula a national punch line.

The Bob Challenged Traditional Views of Femininity

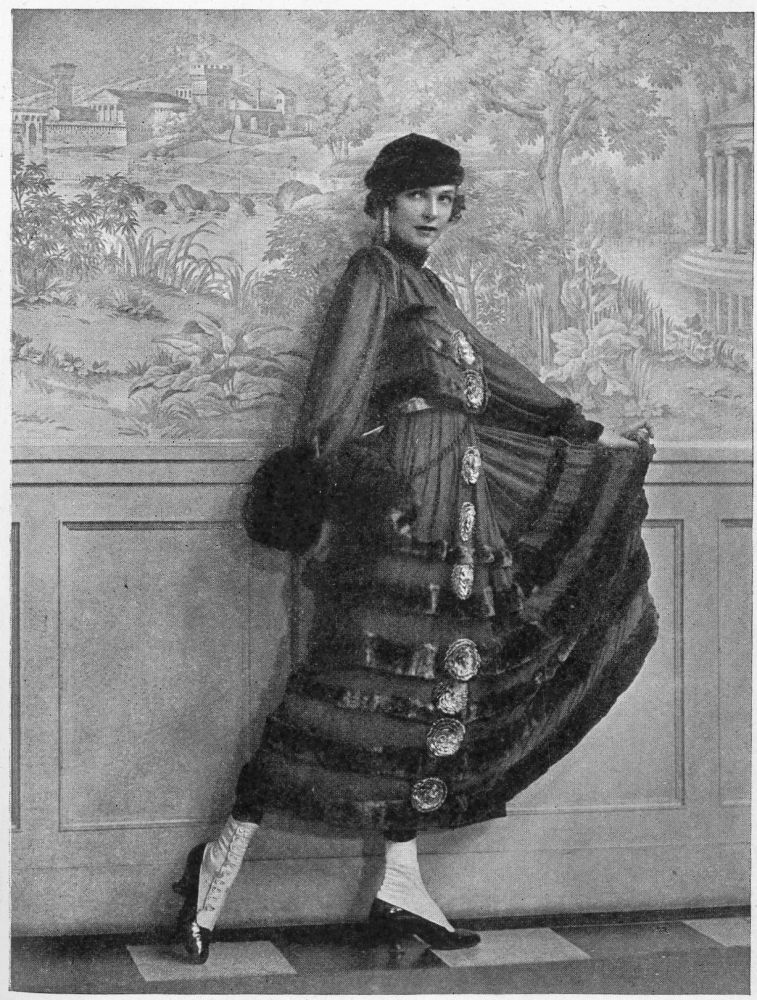

The bob, a distinctive short hairstyle popularized in the 1920s, transcended mere trendiness. Previously, long hair was revered as a hallmark of femininity and allure, contrasting sharply with the perception of short hair as a symbol of masculinity, defiance, and unattractiveness. The groundbreaking bob defied convention and served as a young woman’s bold declaration of modernity and autonomy.

The new generation’s bobbed hair was a dramatic rejection of the norms of their mothers who laboriously styled their long hair into elegant updos or braids. While their mothers had deliberated over suffrage, the younger women sought greater gender equality through new fashion styles and attitudes. They questioned traditional gender roles, epitomized by the slender, boyish silhouette of the 1920s. Fashion-forward women flattened their chests and even dared to wear trousers, with their short hair serving as the focal point of the iconic “flapper” look of the Roaring Twenties.

Antoine de Paris, considered the first celebrity hairdresser, created the bob in the early 1900s based on artists’ depictions of Joan of Arc. It was popularized in the 1920s by film stars such as Mary Thurman and Colleen Moore.

The choice to bob was not a simple decision for many young women. While they wanted to be fashionable and modern, cutting their long locks was not an easy decision to reverse. Some feared it was a passing trend that might look ridiculous in a year when it went out of style.

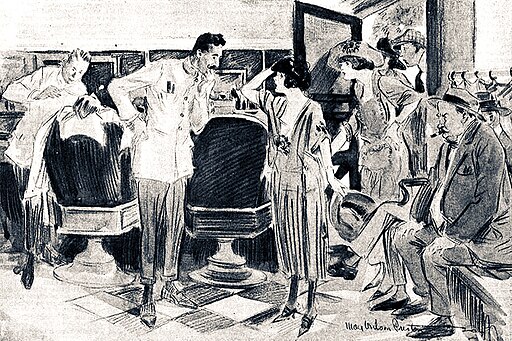

Hairstylists Unprepared for the Bold New Look

Many traditional women’s hairstylists outright refused to perform the highly contentious blunt cut. Other stylists were willing but lacked the expertise, having only used shears for trimming the ends of long hair. Some women turned to men’s shops where barbers were eager to cut their hair and had the scissors and clippers needed to do a neat job. In the larger cities, long lines of women stood outside barbershops. Inside the crowded shops, women sat on the floors waiting their turn to be bobbed. Women’s hairstylists realized that to stay in business they needed to embrace the short hair styles. This gave rise to a new industry of predominantly women-owned hair salons. Do-it-yourself remained an option. Both the Ventura Daily Post and the Oxnard Courier ran ads offering electric clippers to “bob at your home.” The bob also inspired new hair accessories. The still-popular bobby pin got its name from holding the hairstyle in place.

Bernice Bobs Her Hair

In May 1920, the Saturday Evening Post published F. Scott Fitzgerald’s “Bernice Bobs Her Hair.” The short story examined the value of femininity, and of what society expected of a young woman in 1920s. In the story, Bernice is a sweet-but-dull young lady who submits to the barber’s shears and is transformed into a smooth-talking vamp by her fickle society-girl cousin. A character in the story asked Bernice, “Do you believe in bobbed hair?” She replied, “I think it’s unmoral. But, of course, you’ve either got to amuse people or feed’em or shock’em.”

The Ventura County press seemed to relish the controversy. In 1922 The Ventura Weekly Post and Democrat described the activities of visiting entrepreneur Henry Kauve who was buying the long locks cut by Ventura women, presumably for “rehabilitating the dome of some elderly dame.” While Kauve encountered his share of rejection, he told the newspaper the pickings were better in Ventura than in any other town of the same size in the Southland. Kauve added, “Why shouldn’t a girl sell her hair if she wants to wear bobbed hair anyhow?” Another story the same year suggested the bobbed hair fad was just a failed barber shop promotion that has run its course. The Oxnard Press-Courier quoted industry insiders who expected “American girls will be buying their hair back at snug prices.” The Simi Valley Star featured predictable comments from men and women. The men said the bobbed women “sure are crazy” and “look like they had a tumble weed turned upside down on their head.” The women retorted, “It’s my hair and my business” and “doesn’t it feel swell? No more hair pins and hair nets.” Young women were embracing the bob. By 1923, one-third of the women on the University of Southern California campus had bobbed hair.’

The Early Influencers

While it is associated with the 1920s, the bob got its 20th century start in 1915. Ballroom dancer Irene Castle cut her hair short before undergoing an appendectomy. She thought short hair would be easier to wash and comb during her recovery. When Castle returned to the dance floor, she wore a turban to cover her bobbed hair. Friends persuaded her to go out to dinner, sans turban and with her hair down, held in place by a pearl necklace around her forehead. Young women loved the wild new look, and the “Castle Bob” was born. But the bob also generated outrage. Preachers warned parishioners that “a bobbed woman is a disgraced woman.” Men divorced their wives over bobbed hair. One large department store fired all employees wearing bobbed hair. Castle was shocked “to see the outcome of my sacrifice of convenience.” She lamented that she was “largely blamed for the homes wrecked and engagements broken because of clipped tresses.”

By 1921, following the lead of the influencers of the time, such as fashion designer “Coco” Chanel and actresses Clara Bow and Louise Brooks, young women began bobbing their hair. The hairstyle was often linked with other “scandalous behavior” such as wearing skirts above the knee, drinking, smoking, and wearing makeup. Opera singer Mary Garden bobbed her hair because she felt “freer without long, entangling tresses.” Garden considered “getting rid of our long hair one of the many little shackles that women have cast aside in their passage to freedom.” The emancipatory spirit was met with resistance elsewhere. A bobbed-hair teacher in Jersey City, New Jersey was ordered by her Board of Education to let her hair grow! The board claimed that women wasted too much time fussing with their bobbed locks.

Misner’s Firing Triggers Outrage and Ridicule

It was not easy being a teacher in the 1920s. Teachers, particularly women, suffered from low social status and low pay. The average annual salary of a worker in the 1920’s was $3,269. But beginning teachers, even in higher-paying California, were paid much less, $2,154 for men and $1,760 for women. According to a history of the Santa Paula Schools, minutes of a trustee’s meeting state that “it is understood that all teachers, by accepting the position (for the following year) do so cheerfully and by doing so agree to remain contented during the school year, or as long as they are teachers in this school.” The trustees set a salary range of $1,600 – $1,900 for the 1923-1924 school year. Three years earlier, 800 teachers formed a union that would become the California Federation of Teachers. During the 1920s, the union would champion a $2,000 minimum annual salary for teachers and object to school boards and school administrators intruding on teachers’ personal lives. There were horror stories of teachers getting fired for failing to vote, infrequent church attendance, criticizing a principal or administrator, and wearing the “wrong” clothing or hair styles. In an era before collective bargaining, most teachers felt helpless and only a few like Misner were brave enough to challenge school authorities.

Misner’s firing triggered a howl of protest. According to The Los Angeles Times, the event generated “more excitement than this community has known for some time.” The trustees and state school officials received hundreds of letters and Misner filed a protest in Sacramento against the board’s action.

The school district trustees, led by H. P. Balcom and A. C. Hardison had passed a resolution over a year earlier to guard against “teachers getting gay and bobbing [their] hair.” The resolution stated it was the board’s “intent to employ no teacher who had her hair bobbed.”

One unsigned protest letter, postmarked Santa Paula, asked the State Commissioner of Elementary Schools, Grace Stanley, “What has hair dress to do with brain power?” Stanley replied that “some of the most intelligent teachers in the state have bobbed their hair.” However, she noted that Misner had worked in Santa Paula for less than a year under a temporary authorization and could be dismissed at the end of her term on the whim of the school board. Stanley concluded, “If she had taught long enough to be a permanent teacher, then it would be necessary for the board in dismissing her to prefer charges and she would be given opportunity to appear before them in her own defense. The only charges which might be brought against her are for incompetence, immorality, or unprofessional conduct. The only one of those charges which bobbed hair could come under would be the last, that of unprofessional conduct, but since the precedent for that particular style of hair dressing has been quite firmly established, it would seem impossible to bring such a charge in good faith.” She added, “My own hair is bobbed, and I can readily understand your feelings…I would suggest that instead of losing her temper it might be well for the teacher you mention to shake the dust from her feet and seek employment in some community that is more liberal in its attitude.”

The excitement in Santa Paula was not dying down. Other teachers expressed a desire to bob their hair. The controversy spread among the parents of school children. Outside of the community, the trustee’s edict was scorned and mocked. A San Francisco woman, who signed her name Mrs. McLean, wrote the San Francisco Call, and said that the “old fogey superintendent…belongs back in the stone age” and insisted that “men stop meddling in such small affairs as women’s hair and dress.” Mrs. McLean added she was “no flapper or jazz baby, but I am 62 years old and know whereof I speak.”

The Stockton Evening and Sunday Record wrote the firing “looks like a case of peeve and arrogance. There’s as much logic to his action as dismissing a man teacher because he wears a moustache.” The San Francisco Examiner sarcastically suggested women should return “to the days of bustles, dragging skirts, high corsets, and leg of mutton sleeves.” The newspaper concluded, “Three cheers for Santa Paula and the year 1873.”

The Fresno Morning Republican lashed out against one of the school trustees by name in a column entitled, “Attention Mr. [A. C.] Hardison, “the educated ignoramus, who bosses the school.” The San Francisco Bulletin railed against “bobbed hair and bigotry” questioning the intelligence of the superintendent when a schoolteacher is dismissed “because her tresses are not trimmed in a manner pleasing to her official superior.” Misner’s story was picked up by dozens of newspapers including the Detroit Free Press, the [Covington] Kentucky Post and Times Star, the [Denver] Colorado Statesman and even the Windsor Star in Ontario, Canada.

The public, particularly men, remained divided over the bobbing issue. Reader Martin Strong wrote The Long Beach Telegram and The Long Beach Daily News, “To my way of thinking, bobbed hair shows a spirit of ‘I don’t give a damn what people think about the way I do, and that goes for any other thing that I might take a notion to do.’” The Santa Paul Chronicle editors wrote, “If it is the board’s opinion that a lady teacher is more apt to do good and successful work if she wears her hair long, and issues orders to that effect, one accepting employment under such orders is supposed to obey them.”

Others were quick to make the Santa Paula school trustees the butt of jokes. The Simi Valley Star mocked Santa Paula for “living up to its reputation as ‘long-hair’ town in so far as making taboo bobbed hair schoolmarms.” A tongue-in-cheek editorial in the Ventura Daily Post suggested, “It is said the national association of hair pin manufacturers will shortly draw up resolutions expressing regard and esteem for the Santa Paula School Trustees.” In Sacramento, the Superintendent of Education Charles C. Hughes, said he did not care how women did their hair. “The only hair I care about,” said Hughes, “is my own and that is fast slipping.”

Misner Keeps Her Bob and Finds a New Job in Los Angeles

Amid the growing controversy, Misner quickly found a new job. Misner told the Los Angeles Evening Citizen News she was “glad she was fired.” She now had “a far better position in the local [Los Angeles] schools, with the question of hair not entering her working conditions at all.” The Los Angeles Times reported Misner had dropped her protest filed in Sacramento. She said, “My supervisor has advised me not to talk about the matter. I am going to let it drop so far as I am concerned, and do not hold any grudge against the Santa Paula Board.” The Long Beach Telegram and The Long Beach Daily News editors wrote “now that she has a job in Los Angeles, and her hair is still bobbed, she can still call her soul and her personality her own – and she need never soil her shoes again with the dust of Santa Paula.”

Meanwhile, the remaining Santa Paula school teachers asked for a meeting with Superintendent Jones. The Ventura Daily Post reported that the school trustees, “who are bidding for immortality by passing the ‘thou shalt not bob thy hair’ order,” had rejected calls to reverse their decree. They reasoned that changing the rule “would be unfair to the young lady who had already paid the penalty for her bob.” Jones told the teachers the bob ban would stand, at least until the next school year. He emerged from the meeting and claimed, “everything is amicable,” which the Post interpreted as a sign the teachers “have decided not to bob if they had figured on bobbing until the trustees change the order against it.”

The national attention caused by the Santa Paula controversy left the State Department of Education in a bit of a knot. It had to proceed cautiously with what would be seen as a precedent-setting statement. Assistant State Superintendent of Public Instruction Sam H. Cohen unequivocally stated that bobbed hair was not legal grounds for the dismissal of a teacher. He added that the law gives school superintendents no authority to prescribe styles of hair dress for instructors of either sex. While permanent teachers cannot be fired for cutting their hair, temporary teachers may be dismissed at the end of the term, but the way they wear their hair cannot be a factor in the case. The Modesto Bee suggested if the state board took a stand against bobbed hair, their action would have resulted in a shortage of schoolteachers as at least half of the incoming teaching school graduates had bobbed hair.

Santa Paula Voters Have the Last Say in the School Board Election

While the issue might have been settled in Sacramento, the Santa Paula community would still weigh in. Election day was less than two months away. Although school board elections typically attracted limited attention, Santa Paula hosted one of the most fiercely contested school board elections in Ventura County’s history. Voter registration surged in Santa Paula, eclipsing both Oxnard and Fillmore. The election focused on the question of retaining Superintendent Jones. Jones’ opponents waged a write-in campaign against the two trustees who had supported the Superintendent, Balcom and Hardison. Howard Tubbs and Mrs. L. B. Hogue easily outdistanced the incumbents and were elected.

Six weeks after the election, Superintendent Jones resigned. The Ventura Daily Post reported the “reason for Jones’ resignation is not known” while the Simi Valley Star pointed out that after the two trustees who had stood with Jones went down to defeat in the March election, “Jones’ resignation coming at this time is the easier way out.” Jones landed on his feet and found a new job before the end of the month as Superintendent of the Hermosa Beach city schools. The Los Angeles Times made no mention of the bobbing incident, simply stating Jones had been “superintendent of the Santa Paula schools for the last five years and comes here highly recommended.” Santa Paula also moved on. The superintendent of the Santa Cruz schools, George S. Bond, replaced Jones and assumed his new duties at the beginning of the new school term on June 1st.

The Ventura Morning Free Press took one last barb at Jones when it reported that the superintendent who had triggered a state-wide protest had “become the victim of cupid and has married one of the [Santa Paula] teachers who wore her hair long on his order.” The 42-year-old Jones and 25-year-old Geneva Kincaid were married in Los Angeles in June.

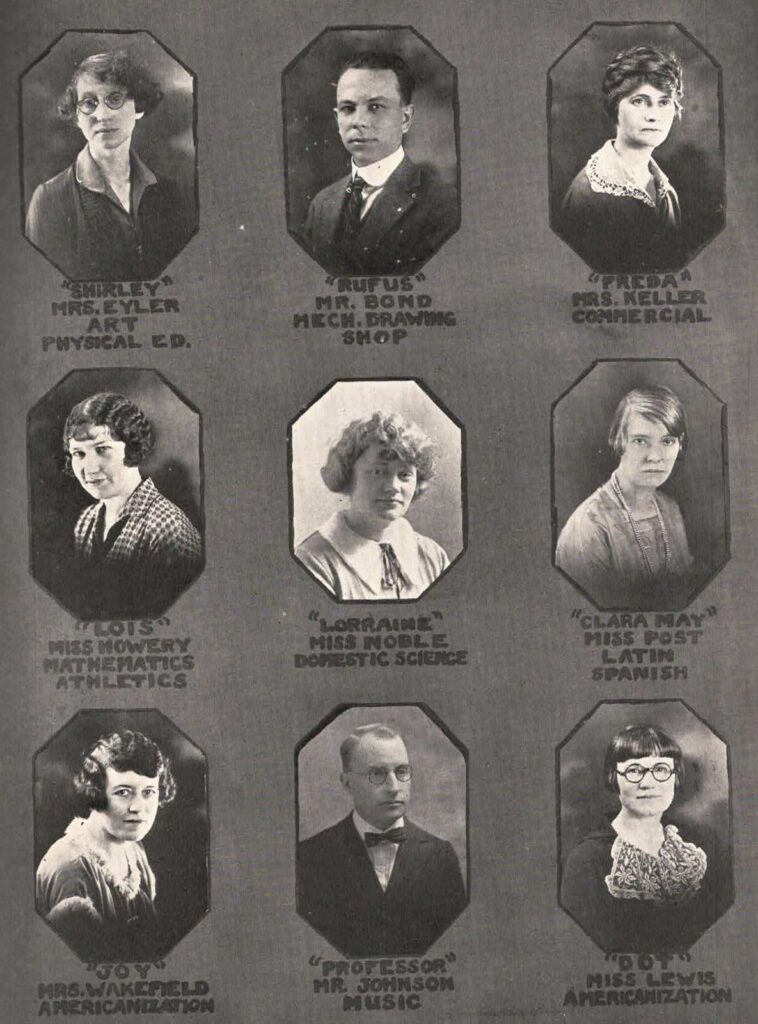

With Jones’ resignation and the ousting of his supporters from the school board, the trustees lost their appetite for restricting the increasingly popular hair style. By the next year, 1925, yearbook photos show most of Santa Paula’s female faculty with short hair styles.

Santa Paula wasn’t the only community struggling with the issue of teacher’s hair styles. The Ventura Morning Free Press reported that New Castle Pennsylvania teachers with long hair would receive a $100 raise, while bobbed haired teachers would get nothing unless they agreed to grow their hair back. In 1924, female graduates with bobbed hair had a hard time getting teaching jobs. But only a year later, Dean Albert S. Hurst of the Teacher’s College at Syracuse University said not a single community listing teaching vacancies with him made any stipulation about the hair length of candidates applying for teaching positions.

In Ventura County, the newspapers continued to enjoy stirring the pot with odd hair bobbing stories from across the nation. The Ventura Morning Free Press reported on a standoff between 17 patrons of a Washington D.C. barber shop and their wives. The men threatened to “let our beards grown until they reach our shoes” if their wives cut their hair. The Free Press editors took an unusual stance when they said, “if man has any inherent right to remove or abridge the hirsute adornment given him by the Creator, woman probably has the same right.”

The Oxnard Press Courier told the story of a Detroit woman who beat a barber on the head with rock wrapped in a handkerchief when he began cutting her hair when she had only gone into the shop for a consultation. The Ventura Morning Free Press interviewed 10 men, asking them, “Which do you like best, bobbed or long hair?” Of the 10 men, four approved of bobbed hair. Miss America 1924, 18-year-old Ruth Malcomson of Philadelphia said, “I don’t think I’m a flapper, although I believe I’m a modern girl. I wanted to bob my hair recently, but my mother stopped me. I’m glad she did now.” The Ventura Weekly Post and Democrat on its “Society” page described a tea held by 30 members of the Methodist Church in honor of five church ladies who had recently bobbed their hair. It was dubbed by the paper as the “bobbed hair tea.” Another church lady was not as supportive. The Ventura Morning Free Press quoted a Boston bible teacher who predicted the “mannish” fashion will last only a short time, “until long hair again comes into its former glory.”

The Nation’s Biggest Movie Star Cuts Her Trademark Curls

Through most of the 1920s, the country’s most famous actress, Mary Pickford had stayed out of the bobbed hair controversy. Known as the “girl with the curls,” the silent film star had carefully cultivated an image attractive to women. Pickford said, “I am a woman’s woman. My success has been due to the fact that women like the pictures in which I appear.”

In a 1927 interview, Pickford admitted being attracted to the short hair styles, but had “resisted valiantly.” She acknowledged her golden curls had become her trademark and lamented that “no matter what my desires, that I am dedicated to little-girl roles for the rest of my screen life, and the curls here, of course, are invaluable to me.” She added, “I am by nature conservative and even a bit old-fashioned, which is a dreadful thing to admit in this day and age…there is no use denying the fact, no matter how much I should like to do so, that I am not a radical.”

While perhaps not a radical, Pickford was far from a pushover. After learning movie producers intended to clamp down on actors’ wages, she formed United Artists in 1919 with other filmmakers including D.W. Griffith and Charlie Chaplin. Pickford had become a powerful, creative force in Hollywood with complete control over her films.

Pickford claimed except for her bangs as a child, scissors had never touched her hair. She curled and brushed her own hair, not trusting anyone other than her mother to assist her, because it needed to be handled gently to keep the famous curls in place.

But as she grew older, Pickford worried her golden locks might be holding her back. The curls had given her “a badge of respectability… mothers trusted those curls as they trusted their own consciences.” But, now in her mid-thirties, she felt trapped in her image that was very different from that of the sassy, sexy actresses of the time such as Bow and Brooks. She said she couldn’t go on being “Rebecca and Tess and Pollyanna and Annie” forever. Pickford said, “I want to wear smart clothes and play the lover.” The silent film character she had created was “practically finished” and she feared she would lose the more adult and sophisticated parts that would be coming with the talking pictures.

By early 1928, Pickford was 36 and her career was at its peak. She had co-founded the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences the year before. She was married to the legendary actor Douglas Fairbanks and had released what would be her last silent film, My Best Girl. In March, her greatest supporter and ally, her mother Charlotte, died from breast cancer.

Pickford finally felt free to “take a courageous stand, once and for all.” On June 22, 1928, she walked into Charles Bock’s Fifth Avenue hair salon in New York. Pickford said as Bock gripped the shears, “I had the feeling he needed aromatic spirits of ammonia more than I did.” Off came the 20 or so famous golden ringlets. As she held them in her lap, she said, “Well, they’re gone and I’m glad.” Bock trimmed her remaining hair into a stylish, still curly cut. Pickford paid Bock five dollars and took her curls back to her hotel.

The end of the world’s “most famous and most photographed golden curls” made the front page of the New York Times as well as most major newspapers in the country. She told the Times she had her curls “ready to be pinned on if I ever need them.”

But with her new look Pickford was ready to experiment with the new technology. She made her first talking film, Coquette, where she played against type as a flirtatious, bobbed haired flapper with her skirt above the knee.

It was well received by audiences and critics. In April 1929 the Ventura Morning Free Press noted the picture’s four day run at the Ventura Theater was a chance for the public to “have their first opportunity to hear her speak and also to see her without her famous curls.” The newspaper would add the picture’s “heart-wrenching realism tests the very soul of the Pickford genius. Her appearance in a windblown bob for which she sacrificed her famous curls, will complete the surrender of her admiring world to the new order of things in the amazing Pickford career.” The Ventura County Star claimed her “neat bob is probably the most beautiful blonde hair in Hollywood.”

Pickford won the second-ever Best Actress Academy Award for her performance in Coquette. She said for the great satisfaction of winning the Academy Award, “my curls had been a very small price to pay.” However, after her initial talkie success, Pickford’s career faded as audiences failed to respond to her in similar roles. She appeared in three more films before her retirement from acting in 1933. As for Pickford’s cut curls, she gifted several locks to the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County where they remain one of the most popular items in the museum’s collection.

Hairstyles Often Go Beyond Fashion Statements

Throughout the 1920s, so-called experts predicted the end of bobbed hair. The Oxnard Press Courier reported that insiders at the International Hairdressers’ Congress in Paris in 1924 believed that bobbed hair like hooped skirts had become passé. They said, “all Europe has quit bobbing” and in six months America will find it to be “atrociously unpopular, if not in utter bad taste.”

Of course, bobbing has never gone away.

Make History!

Support The Museum of Ventura County!

Membership

Join the Museum and you, your family, and guests will enjoy all the special benefits that make being a member of the Museum of Ventura County so worthwhile.

Support

Your donation will help support our online initiatives, keep exhibitions open and evolving, protect collections, and support education programs.

Bibliography

- “1920s: The Condition of the Teachers.” California Federation of Teachers. Accessed February 7, 2024. https://www.cft.org/post/1920s-condition-teachers#:~:text=The%20’Jazz%20Age’%20wasn’,to%20a%20principal%20or%20administrator.

- “Beyond the Bob: 1920s Hairstyles for the Rapunzels Among Us.” History Research Shenanigans. Last modified February 2, 2015. https://historyboots.wordpress.com/2013/07/26/beyond-the-bob-1920s-hairstyles-for-the-rapunzels-among-us/.

- “The Bob.” The Hair Archives. Last modified September 10, 2019. https://www.hairarchives.com/private/1920s.htm.

- Bradley, Irene. “The Long and Short of It.” Simi Valley Star, February 23, 1922.

- Duke, Mabel. “How Moviedom’s Famous Blonde Cares for Hair.” Ventura County Star, October 11, 1929, 9.

- The Fresno Morning Republican. “Two Mouthfuls o’Nothing.” February 16, 1924, 4.

- “History Daily.” History Daily. Accessed February 7, 2024. https://historydaily.org/the-bob-a-revolutionary-and-empowering-hairstyle/3.

- Long Beach Telegram and Long Beach Daily News. “Cato on Bobbed Hair.” February 24, 1924, 14.

- Los Angeles Evening Citizen News. “Rush to Defend Bobbed Hair for School Teachers.” February 13, 1924, 1.

- Los Angeles Evening Express. “Bobbed Hair is Knot Before School Board.” February 9, 1924, 1.

- Los Angeles Times. “Bobbed-Hair Teacher Fired.” February 10, 1924, 122.

- Los Angeles Times. “Bobbing of Hair Brings No Regrets.” February 13, 1924, 19.

- Los Angeles Times. “Santa Paula Gets a New School Head.” May 18, 1924, 104.

- Los Angeles Times. “School Head Named for Hermosa Beach.” May 21, 1924, 12.

- “Mary Cuts Her Hair.” Mary Pickford Foundation. Last modified June 20, 2018. https://marypickford.org/caris-articles/mary-cuts-her-hair/.

- “Mary Pickford Secretly Has Her Curls Shorn; Forsakes Little-Girl Roles to Be ‘Grown Up’.” TimesMachine: Tuesday March 20, 1979 – NYTimes.com. Last modified June 23, 1928. https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1928/06/23/91529851.html?pageNumber=1.

- “Mary Pickford: From the ‘Girl With the Curls’ to ‘Woman’s Woman’.” Silent London. Last modified January 13, 2014. https://silentlondon.co.uk/2012/03/08/mary-pickford-from-the-girl-with-the-curls-to-womans-woman/.

- The Modesto Bee. “Bobbed Hair Vindicated.” February 12, 1924, 4.

- Morning Free Press (Ventura). “Bobbed Hair Said Opposed to Bible.” July 9, 1925, 2.

- Morning Free Press (Ventura). “Bobbed Hair is No Bar to Teachers.” June 9, 1925, 4.

- Morning Free Press (Ventura). “Bobbed Hair is Stirring Row at Santa Paula School.” February 9, 1924, 1.

- Morning Free Press (Ventura). “Bobbed Name Latest Fad of School Teacher.” February 11, 1924, 1.

- Morning Free Press (Ventura). “County News Clippings.” July 22, 1924, 4.

- Morning Free Press (Ventura). “Half Minute Interviews.” February 16, 1925, 4.

- Morning Free Press (Ventura). “Men Bob Hair, Why Not Women.” February 13, 1924, 1.

- Morning Free Press (Ventura). “One Contest in County School Elections.” March 29, 1924, 1.

- Morning Free Press (Ventura). “Penalty for Bobbed Hair.” April 1924, 2.

- Morning Free Press (Ventura). “Theaters.” May 1, 1929, 3.

- Morning Free Press (Ventura). “Theaters.” April 30, 1929, 3.

- Morning Free Press (Ventura). “Tresses and Beards.” August 25, 1924, 2.

- “The New Woman of the 1920s: Debating Bobbed-Hair.” History Matters: The U.S. Survey Course on the Web. Accessed February 7, 2024. https://historymatters.gmu.edu/d/5117/.

- Oxnard Press Courier. “Ad: Hand Toilet Clippers.” November 19, 1924, 4.

- Oxnard Press Courier. “Beauty Congress Meeting in France Sounds Death Knell of Bobbed Hair.” March 28, 1924, 2.

- Oxnard Press Courier. “Beauty Queen Will Not Let It Affect Her Head, She Says.” October 22, 1924, 6.

- Oxnard Press Courier. “Bobbed Haired Girls Will Buy Back Locks is Expert Prediction.” June 7, 1922, 4.

- Oxnard Press Courier. “Girl Hits Barber With Rock For Giving Her a Bob She Didn’t Want.” September 9, 1924, 3.

- Raitt, Robert L. Campus on the Hill : The Story of Santa Paula High School and a Century of Community Yesterdays. Santa Paula, CA: Santa Paula Union High School Alumni Association, 1988.

- Riverside Daily Press. “Bobbed Hair No Bar to Teaching in Sacramento.” February 13, 1924, 2.

- San Francisco Bulletin. “Bobbed Hair and Bigotry.” February 13, 1924, 14.

- San Francisco Examiner. “Bobbed Locks Defended.” February 10, 1924, 5.

- San Francisco Examiner. “Put ’em in Stripes.” February 11, 1924, 22.

- “The Scandal of Mary Pickford’s Curls.” Let’s Misbehave: A Tribute to Precode Hollywood. Accessed February 7, 2024. https://www.precodemisbehaving.com/2013/07/the-scandal-of-mary-pickfords-curls.html.

- Simi Valley Star. “Couldn’t Make Fish of One and Foul of Another.” February 21, 1924, 1.

- Simi Valley Star. “Superintendent Jones Takes the Easy Way Out.” May 22, 1924, 1.

- Simi Valley Star. “U.S.C. Co-eds Keep Shorn Locks Short.” March 15, 1923, 3.

- Simi Valley Star. “Venturans File Protest Against Concessions.” February 14, 1924, 5.

- Spivack, Emily. “The History of the Flapper, Part 4: Emboldened by the Bob.” Smithsonian Magazine. Last modified February 26, 2013. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/arts-culture/the-history-of-the-flapper-part-4-emboldened-by-the-bob-27361862/.

- Stockton Evening and Sunday Record. “Record Passed by the Censor.” February 9, 1924, 22.

- Ventura County Star. “Film Notables Receive Honors for 1929 Work.” April 4, 1930, 10.

- Ventura Daily Post. “Ad: First class electric clipper.” July 16, 1924, 2.

- Ventura Daily Post. “Bobbed Hair Rule Starts Emancipation Complex Among Girls.” February 20, 1924, 1.

- Ventura Daily Post. “Editorial.” March 2, 1924, 2.

- Ventura Daily Post. “Far Seeing Santa Paula Trustees Made Ruling Year Ago.” February 10, 1924, 1.

- Ventura Daily Post. “Santa Paula Teacher Fired for Bobbing Her Hair She Claims.” February 9, 1924, 1.

- Ventura Daily Post. “Santa Paula’s Anti Bobbing Rule to be in Effect This Year.” February 17, 1924, 1.

- Ventura Daily Post. “School Chief of Santa Paula Quits.” May 16, 1924, 1.

- Ventura Weekly Post and Democrat. “Hair Gatherers Do Flourishing Business Here.” June 30, 1922, 8.

- Ventura Weekly Post and Democrat. “Society.” November 27, 1925, 6.

- ““Do You Believe in Bobbed Hair?” Asked G. Reece in the Same Undertone. “I Think It’s Unmoral,” Affirmed Bernice Gravely. “But, of Course, You’ve Either Got to Amuse People or Feed’em or Shock’em.”.” Clarke Historical Museum. Accessed February 7, 2024. https://www.clarkemuseum.org/blog/do-you-believe-in-bobbed-hair-asked-g-reece-in-the-same-undertone-i-think-its-unmoral-affirmed-bernice-gravely-but-of-course-youve-either-got-to-amuse-people-or-feedem-or-shockem.