Written by Andy Ludlum, Library Volunteer

Recorded interviews in the Research Library’s oral history collection give us a glimpse into the lives of two remarkable women who were members of the earliest African American families to settle in Ventura.

One woman’s story is an example of selflessness and courage, caring for the sick during the deadly flu outbreaks that started with the 1918 pandemic and lasted into the 1920s. She did all this as racial prejudice denied her the opportunity to work, as she had been trained, as a hospital nurse.

Both women experienced the suffering caused by the yearly flooding of the Ventura River. Their stories also reveal the hurt caused to their families by a tragic fire and the circumstances that led to the death of two children.

The Nurse No Hospital Would Hire

According to her own and her family’s recollections, as well as a number of published sources, Cerisa House Wesley’s birth in 1898 was the first recorded birth of an African American child in the city of Ventura. The 1900 Census lists 20 “Blacks” in Ventura County. By 1910 that number had increased to only 31.

As a young woman Cerisa traveled to Harpers Ferry, West Virginia to attend Storer College, one of the first African American colleges, where she studied to be a nurse. Cerisa said since she was a small child she had loved nursing, but she knew at that time it was difficult for African Americans to obtain the training. In the spring of 1918 an influenza outbreak spread worldwide from Army camps in Kansas. With World War I still raging, parts of the U.S. and Europe fell victim to this fast-spreading, unusually severe form of flu. About one in four Americans got the flu and 675,000 people died. Smaller flu outbreaks continued into the 1920’s in Ventura County, most notably in Oxnard. Cerisa returned to Ventura in 1923 as a qualified nurse, but since she was labeled as a “Negro” she was unable to find a job as a hospital nurse. She told Museum of Ventura County docents in a 1980 recorded interview:

Cerisa worked with poor and dying influenza patients in Oxnard, caring for them in their homes. Neighbors and even family members were often reluctant to help, fearing they too might be stricken. Leaders of the nursing profession today acknowledge that during this period, nursing jobs remained predominately limited to whites. African Americans had only limited access to nursing education and employment. These prejudices limited the supply of skilled nurses when they were needed the most.

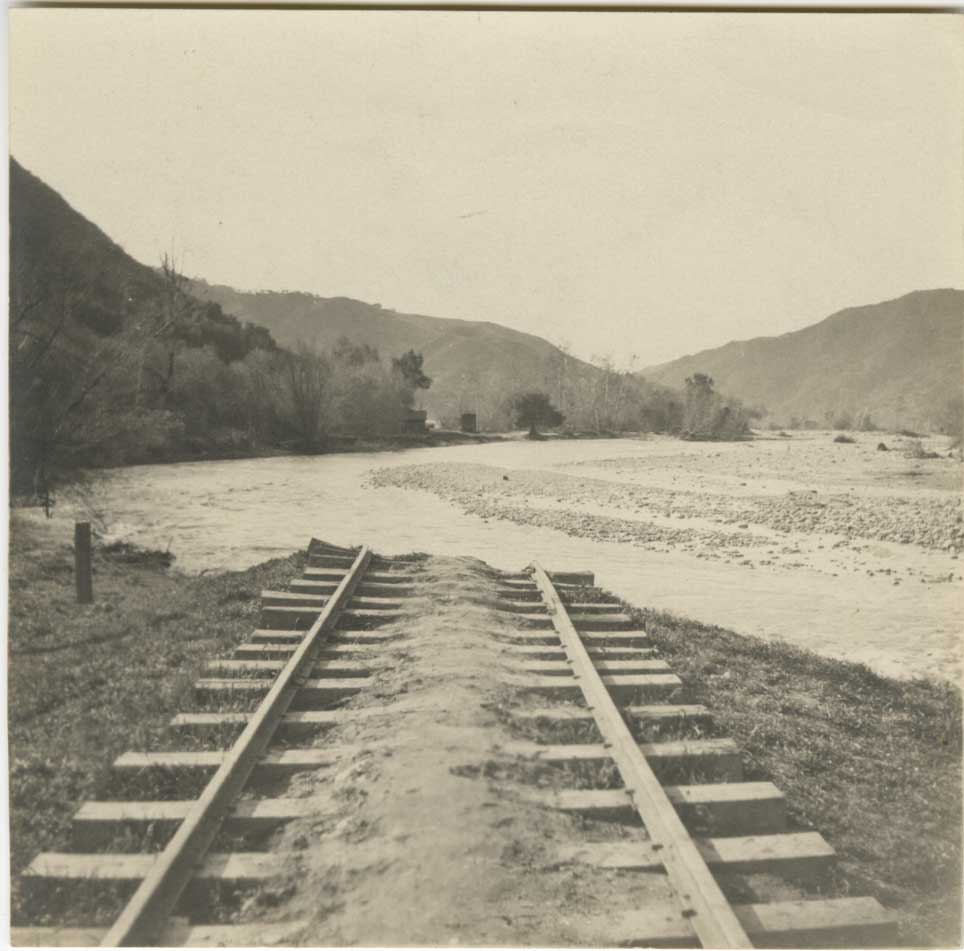

Devastating Annual Floods

Annie Smith was another member of one of Ventura’s first African American families. Born in 1903, she was Cerisa’s aunt even though she was five years younger. Both Annie and Cerisa remember the annual flooding of the Ventura River that would threaten their Front Street home in an area that came to be known in the 1930’s as Tortilla Flats. Cerisa said flooding would come every year until levees were constructed on the river banks:

In a 1979 interview with Museum docents, Annie remembered a particular flood in 1909:

The horses had to swim in to rescue Annie’s mother. And her brother, Rainey, was named because of the storm. Annie said when Rainey died in 1974, it poured rain on the day of his funeral.

Children Lost in Tragic Fire

As well as flooding, Cerisa and Annie’s families had to contend with another threat, fire. Their wood frame houses were particularly susceptible to embers spread by accident or scorching Santa Ana winds. The tragedy of one particular fire scarred both families and the community for years.

Annie says she was six years old when her mother left her at home with her siblings, five year old Ventura and four month old Jimmy when she went across the street to visit with her sister. When fire broke out in the house, Annie ran across the street to alert her mother. The only problem was she couldn’t talk.

Cerisa remembers looking out the door and seeing Annie’s house go up in flames.

Both children were buried in the city cemetery, two of the now mostly-lost graves in Cemetery Memorial Park.

Surge of KKK Activity in the 1920s

In their recorded interviews, neither Annie nor Cerisa described a great deal of racial tension in the first decades of the 20th century. Annie described Ventura as “quiet, like a big family.” Cerisa’s account is similar. They also did not have much to say about a surge in Ku Klux Klan activity in Ventura County in the 1920’s. Annie says she was never intimidated or harassed and didn’t remember much about the Klan.

In the Library’s microfilm records of the Ventura Free Press, there is a front-page article on a planned Klan rally to be held July 28, 1923 at the Stanley Park Lodge south of Carpinteria. The article matter-of-factly describes what was billed as “one of the biggest open air demonstrations in the history” of the Klan. It concludes with a paragraph quoting, without comment, the “purported creed of the organization” including “the eternal maintenance of white supremacy” and the preservation of the “constitutional rights and privileges of a free born Caucasian race…”

Final Notes on Cerisa and Annie

Cerisa House Wesley died at age 85 on September 8, 1983. Cerisa was never able to use her nurse’s training in a hospital. Instead, she took care of children and worked as a practical nurse. She told a newspaper reporter in 1974 that she didn’t bear any grudges against those who refused to hire her as a hospital nurse. Cerisa also turned down the same reporter’s request to take her picture. “People who know me know what I look like,” she said, “and people who don’t know me don’t care.” In 1974 she was honored by the Ventura County Board of Supervisors for her contributions to the county, including being a founding member of the Olivet Baptist Church, a longtime NAACP member and a volunteer with the County Medical Center auxiliary.

Annie Smith died April 20, 1987. She was 84. Annie worked as a housekeeper for 70 years. She was a member of the Order of the Eastern Star and the Avenue Senior Citizens Committee. She also helped with the Ventura County Fair for over 40 years. When she died, she had two grandchildren, seven great-grandchildren and one great-great grandchild.

Make History!

Support The Museum of Ventura County!

Membership

Join the Museum and you, your family, and guests will enjoy all the special benefits that make being a member of the Museum of Ventura County so worthwhile.

Support

Your donation will help support our online initiatives, keep exhibitions open and evolving, protect collections, and support education programs.

Bibliography:

Books

- Goldwyn, Gail M. with Gibson, Jr., Leroy A. Looking Beyond the Mirror. The Untold Story of Growing Up African American in 20th Century Ventura County, California. 2017 Gail Goodwyn’s Books, Woodinville, Washington. (Not yet in the Library’s collection but available on Amazon.com.)

- African-Americans On The Central Coast. A photo essay depicting aspects of the life of the African-American community in the counties of San Luis Obisbo, Santa Barbara, and Ventura. 1993 Black Gold Cooperative Library System.

Oral Histories

- Interview with Annie R. Smith. April 11, 1979. Conducted by Mary Johnston and Kay Murphy.

- Interview with Cerisa House Wesley. February 5, 1980. Conducted by Mary Johnston and Gerry Browning.

Newspaper Clippings

- Wagner, Dennis. A quest for vanishing treasure. Ventura woman is saving precious memories of yesteryear. Ventura Star Free Press, September 25, 1980.

- Obituary, Anne R. Smith. Ventura Star Free Press. April 23, 1987.

- Mrs. Wesley dies at 85; first black born in county. Ventura Star Free Press. September 10, 1983

- Wheeler, Eugenie. Docent’s re-creation does role model proud. Ventura County Star, February 25, 1999.

- Holt, Bob. The Klan once had clout. Ventura Star Free Press, August 3, 1978.

- Klan reached peak in 1920s. But as quickly as it flourished, it died. Ventura Star Free Press, April 8, 1979.

On Microfilm

- Klan gathering this evening Stanley Park. Ventura Free Press, February 28, 1923.