by Library Docent Volunteer Andy Ludlum

Even after 76 years, John Doughty’s memories as an 8-year-old in 1910 were as clear as if it were yesterday. The Simi Valley man said his mother, Annie, began crying and yelling when she first spotted Halley’s Comet. She fell to her knees and waved her arms up and down in prayer. She was certain the comet was a sign from God, “a cyclone that would burn a hole through the Earth.”

John was “scared to death” by his mother’s reaction but braved a look at the celestial intruder. It was extremely bright and to his young eyes appeared to be the size of the moon, hovering 50 yards above the earth with a 100-yard tail. John remembers his mother telling him and his siblings to clean up and put on their Sunday clothes. “She didn’t know whether we were going to hell or heaven, but she wanted to make sure we were clean when we got there.” When his mother finally realized that nothing was going to happen, the family went back to their regular routine.

The comet that appeared so near in John’s eyes was indeed making one of its closest approaches to Earth, just under 14 million miles. That “100-yard tail” was 24 million miles long in May 1910 and the Earth was on a direct path through the mysterious, gaseous tail.

Halley’s Comet Appears in the Earliest Historical Records

Halley’s Comet has captivated us for thousands of years. It first appears in Chinese historical records in 240 BC. It was named after British Royal Astronomer Edmund Halley when he noted in 1758 that the comet repeatedly returned on a predictable path for millennia. It becomes visible from Earth every 76 years.

Halley is classified as a periodic or short-period comet, meaning it has an orbit lasting 200 years or less. The comet’s path comes nearest the Sun somewhere between the orbits of Mercury and Venus. Its furthest distance from the Sun is roughly the orbital distance of Pluto.

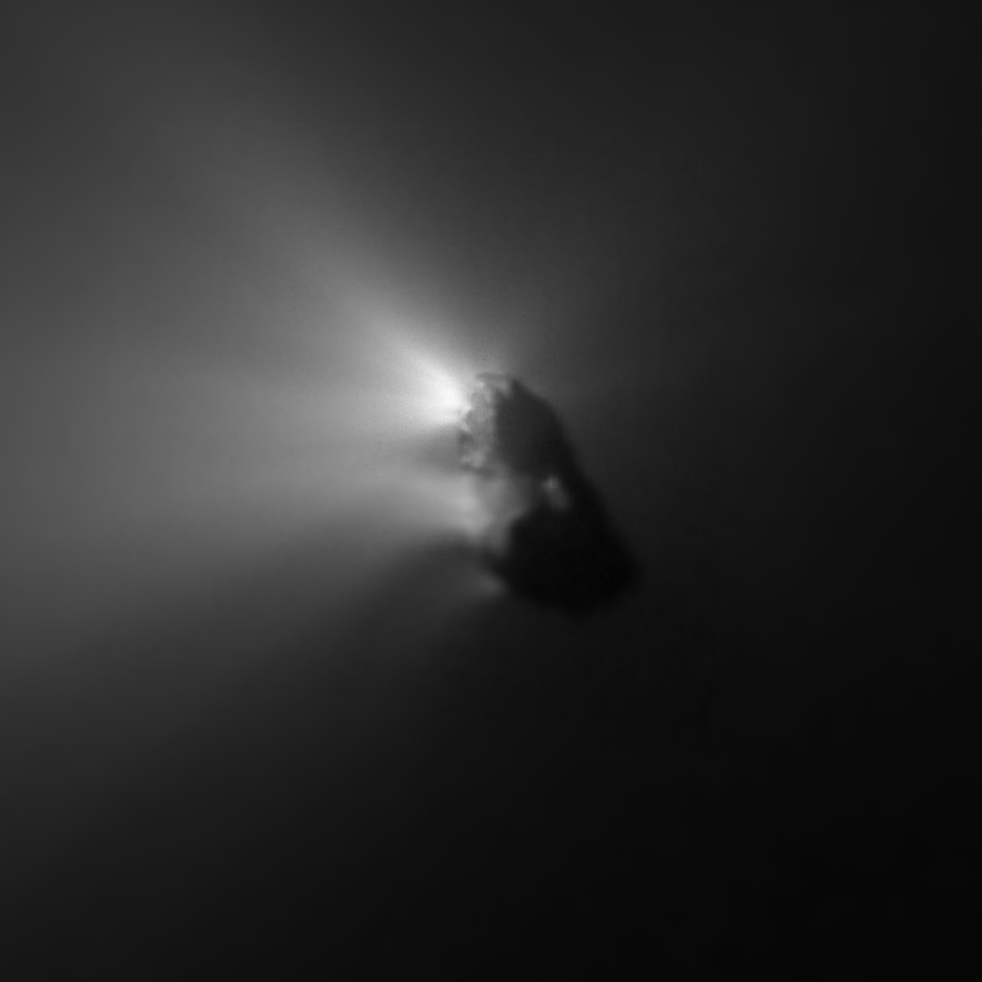

The main body of the comet, or nucleus, is a mix of ice and dust, leading astronomers to call it a “dirty snowball.” As Halley nears the Sun, compounds in the ball with low boiling points begin to vaporize, creating a coma or bright tail of mostly ionized water, methane, ammonia and carbon dioxide that can stretch millions of miles from the nucleus. More recently, astronomers discovered that 90 percent of Halley’s surface is coated in a layer of dark dust that retains heat, leading many of them to change their description of the comet to a “snowy dirtball.” These “non-volatile” materials form a second, fainter tail of the comet consisting of microscopic particles.

Comet’s Arrival Eagerly Anticipated

In 1910, telescopes were powerful enough to track the comet around its 76-year orbit. Its return was highly anticipated and eagerly reported by the newspapers. On January 5th, the Ventura Morning Free Press reported that Halley’s comet “will give the Pacific Coast a close brush this year on May 18…and the phenomenon will be something spectacular.” The newspaper report promised “as dazzling a piece of heavenly fireworks as this generation has ever witnessed” as the Earth passed through the tail of the “celestial visitor.”

Throughout history, the arrival of comets with their long, ominous tails triggered fears, superstitions, and panic. Halley’s was blamed for earthquakes, illnesses, red rain, and even the births of two-headed animals. But for the rest of January 1910, the impending arrival of the comet was met with wonder and amusement. The Morning Free Press gleefully reported that the Chicago Tribune had objected to reports that Halley’s Comet would be best seen on the Pacific Coast. The paper stated, “California must be requested respectfully to cease interfering in the work of the universe. It is not enough that all the sunshine, all the flowers, all the gentle breezes, and all the delights of nature, which we would enjoy if we could, should be penned up and confined on the Pacific Coast? Must California also cabbage the comet?”

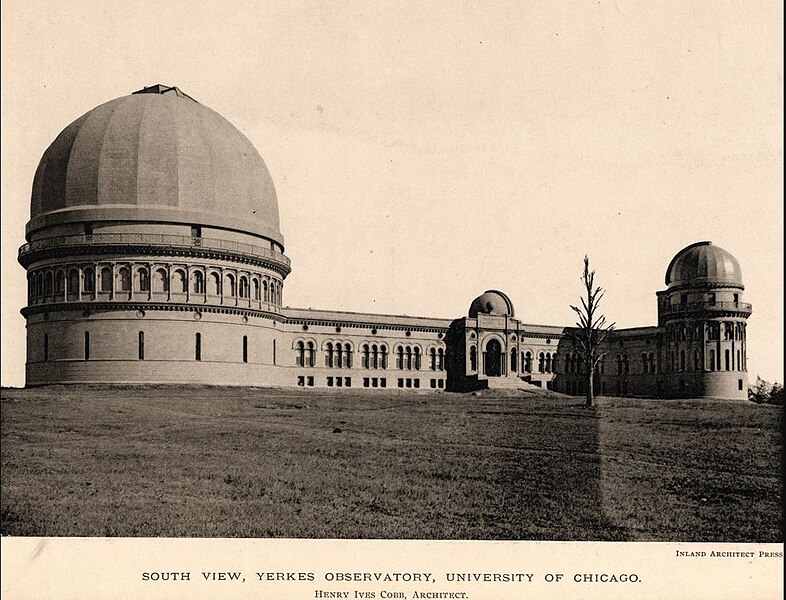

Morning Free Press readers saw regular front page updates on the comet. One noted that Harvard’s Yerkes Observatory had seen a faint tail trailing the nucleus of Halley’s comet. And from the Navy’s Mare Island Observatory came word the comet should be visible to the naked eye between February and July.

While Halley’s 76-year orbit was understood by astronomers in 1910, it wasn’t accepted by some of Ventura’s oldest inhabitants who “pooh-pooh the idea of not having seen the comet before. Frank Newby said he has seen it several times. Charley Whitney even gave dates and brought further proof by naming others who saw it the same time he did.” Amplifying the old-timers’ unreliable recollections, there was about to be a comet mix-up. In late January, the brilliant Comet 1910 A1, also called the Daylight Comet, appeared months before Venturans got their first glimpse of Halley’s Comet.

The Ventura Weekly Post and Democrat editors were all aglow about the “brand new blazer” seen in the evening sky which they expected would be visible for “several weeks to come.” The Morning Free Press quoted an astronomer at Oakland’s Chabot Observatory who called the comet “far more beautiful and pretentious” than Halley’s and “wonderfully bright, brighter even than the glowing Venus.” The Oxnard Courier reported locals saw the comet in the western sky about 6:30 in the evening noting that the “orange color[ed] tail stretched well out toward the zenith and the great glow in the sky attracted people from every part of the county.” Comet 1910 A1 was first spotted by three South African miners as they returned home from work. Five times brighter than Venus, it had a fan-shaped head and a short curving tail. No one who saw the comet in 1910 would see it again as its elliptical orbit takes almost 15,000 years.

Fear of Gasses in Comet’s Massive Tail

While Venturans enjoyed Comet 1910 A1’s nightly displays, astronomers trained their telescopes and instruments on Halley’s which was racing ever closer. As they calculated the comet’s close passage to the Earth, they realized the planet would pass through the comet’s tail which was millions of miles long and growing as it approached the Sun. But in early February, the public’s wonder and amusement with Halley’s grew tense and fearful.

Using the technique of spectroscopy, in which light is analyzed to show its composition, researchers at the prestigious Yerkes Observatory announced the comet’s tail contained cyanogen, a deadly poison. Hydrogen cyanide was a well-known and extremely toxic substance, often used to kill rats in buildings. But things were about to get much worse.

On February 8th, the New York Times ran a short front-page story headlined “Comet’s Poisonous Tail.” The article stated, “Cyanogen is a very deadly poison, a grain of its potassium salt touched to the tongue being sufficient to cause instant death. In the uncombined state it is a bluish gas very similar in its chemical behavior to chlorine and extremely poisonous.” In addition, the Times reported that one of the world’s preeminent popular scientists, Paris-based Camille Flammarion “is of the opinion that the cyanogen gas would impregnate the atmosphere and possibly snuff out all the life on the planet.” The Times dutifully reported that other well-known astronomers disagreed with Flammarion, but the newspaper left most readers with the unsettling thought that the comet could abruptly end life as they knew it.

In fairness, Flammarion’s comments were taken out of context. While a scientist, Flammarion possessed the heart of a poet. Richard Goodrich, in his book Comet Madness: How the 1910 Return of Halley’s Comet (Almost) Destroyed Civilization wrote that Flammarion was “enthralled by the majesty of the heavens and believed that astronomy was a springboard for the imagination. He preferred speculation about what might be over the dry documentation of what was.”

According to Goodrich, newspapers, led by the Associated Press wire service, played up readers’ fears to sell papers. There wasn’t fear mongering in the Ventura newspapers even though much of the initial comet awe and amazement disappeared from their accounts.

While Southern California papers like Pomona’s Progress-Bulletin wrote articles headlined “Will Halley’s Comet Kill Us All,” The Ventura Weekly Post and Democrat proclaimed the “Harmlessness of the Comet’s Tail” quoting San Francisco astronomer Rose O’Halloran who said the “the ethereal appendage may brush both land and sea without any noticeable effect, except, perhaps, a vague yellowish tint in the atmosphere.” The paper also wrote about an argument between two Bakerfield papers, the Californian and the Echo, about whether the comet seen in the evening sky was Halley’s or Comet 1910 A1. The Weekly Post and Democrat doubted either paper knew anything about Halley’s and added “all the concern we have about it is that it keeps its tail up or pointing in some opposite direction from us.”

By mid-February, Halley’s was now visible to astronomers using telescopes. The Ventura Free Press reported that the comet was growing in brilliance and “surrounded by a whitish halo resembling very much the one around the moon when the atmosphere is laden with water vapors.” The account noted that “the comet is suspected of growing an embryonic tail, which the experienced eye just commences to guess at.”

Some Tied to Calm While Others Exploited Public Fears

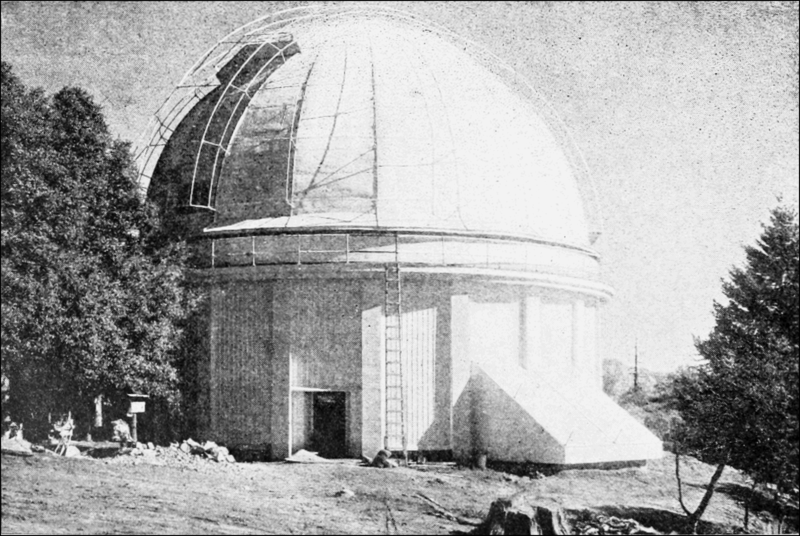

The Ventura Weekly Post and Democrat got right to the point, proclaiming Halley’s was “not an Earth smasher.” The paper quoted French astronomer Henry Chretien, who traveled to use the Mt. Wilson Observatory’s big new telescope to track the comet. “It will be impossible – quite impossible – that Halley’s comet will destroy all the face of the earth when it visits us,” he laughed. “It will be seen only by those having fine instruments, and then not well. As for a union of the hydrogen of earth’s atmosphere and the gases of the comet tail, this will also be quite impossible, and there is little danger of the formation of a deadly poisonous gas inimical to even health, let alone life. The comet gas is far too light to penetrate the earth’s atmosphere.”

Ventura clubs such as the women’s group, The Wednesday Afternoon Club featured discussions on Edmund Halley’s life and the comet. The Ventura Free Press reported wine growers in the state were debating if the comet would have any influence over the 1910 wine crop. This is spurred by a legend promoted by French wine growers that when the comet appeared in 1611, there was a vintage of both exceptional quality and quantity. The so-called “Comet Wine” was highly prized and commanded high prices at European wine auctions.

Halley’s in 1910 brought its share of doomsayers and charlatans ready to exploit the public. A man wrote the Royal Greenwich Observatory in England and claimed the comet would cause massive tides across America as the Pacific Ocean emptied itself into the Atlantic.

Con artists hawked anti-comet (sugar) pills promising to be “an elixir for escaping the wrath of the heavens.” A Los Angeles man, C. B. Green sold comet insurance promising a $500 cash payment to the widow or children of a victim killed by the comet striking the Earth. Policyholders paid 25 cents a week to insure their lives. Green’s contract contained a proviso that death must not be due to fright alone.

Experts Knew “Mighty Little” About Comets

Most people continued to see the comet as a marvel and not as a threat to life itself. But, in 1910, astrophysics was a young enough science to open the door, at least a crack, to doubt. The Los Angeles Evening Post Record collected the opinions of 11 experts and concluded the wise men knew “mighty little” about comets.

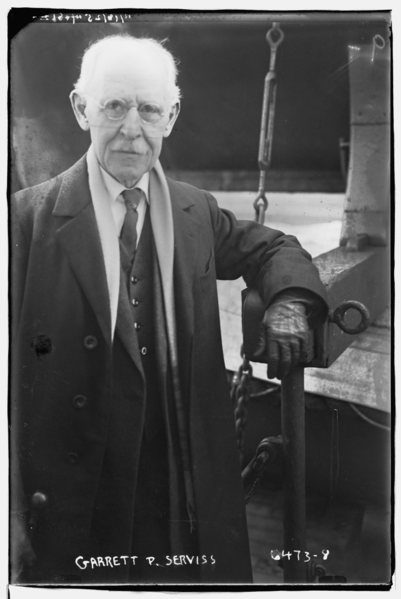

Reacting to Flammarion’s fanciful and frightening prediction, Harvard’s William H. Pickering said the French astronomer “may be right. No man knows.” Astronomer and author Garrett P. Serviss noted that “heavenly bodies are subject to accidents and irregularities” and if something delayed or accelerated the speed of the comet, it might “encounter the Earth” and “there would be disaster unspeakable.” Director of the Meudon Observatory in Paris, Henri-Alexandre Deslandres suggested Halley’s might shoot X-rays which would “condense more water vapor than has been seen since the days of Noah’s great deluge.”

Columbia University’s Harold Jacoby speculated that in the “most improbable” case of the comet striking the Earth, the visible effects would “be no greater than those produced by falling stars.” As for passing through Halley’s tail, Lowell Observatory Director Percival Lowell said the material composing the comet’s tail was so light, nothing would happen on Earth. Dr. John N. Stockwell suggested “the tail is probably gas. It may be harmless and may even do us good.” Other experts predicted no effects on the health, climate, and temperature of the Earth and no visible effects other than light shows and meteor showers.

Religious and Scientific Responses to the Threat

One of the Evening Post Record’s experts was the Reverend Frederic Campbell, Doctor of Science and President of the Department of Astronomy at the Brooklyn Institute in New York. He offered a religious rather than scientific assurance that Halley’s tail posed no threat and called it “unbelievable that the Maker of the universe will permit some chance wanderer to defeat the divine purpose, as shown in human existence and human endeavor of almost countless centuries and put an end to the home of the highest form of life that He has fashioned.”

Beginning in April, the Ventura Free Press published a weekly series of five articles on Halley’s comet written by Campbell. The dense, thousand-word articles described the dimensions, structure, and appearance of the comet as well as the history of its path through the solar system. Cambell didn’t shy away from using astronomical science to assure the readers that Halley’s was not a threat. He pointed out that when the comet was closest to the Earth, it would still be six million miles away, or “24 times the distance of the moon.” As for the long, sweeping tail, Campbell compared it a searchlight which illuminates “the finest particles of dust and moisture which happen in its way, giving an impression of substantiality far beyond the facts.” He said if a child walked through the beam of a searchlight, they would not be disturbed “in the least.” He argued the comet’s tail was the same and called it “one of the most unsubstantial things in the universe.” Yet he still considered the comet to be a special “visitor that has come for quite a sojourn giving every human eye the world over the opportunity not only to witness one of the most marvelous apparitions of the heavens but to watch and study it in all its details.”

The Ventura newspaper editors seized every opportunity to encourage readers to reject the sensational accounts of doom in favor of more level-headed reporting. The Ventura Weekly Post and Democrat quoted astronomer Robert Aitken at the Lick Observatory on Mt. Hamilton near San Jose. Aitken said “the sensational predictions have been made by persons who are not professional astronomers. There is absolutely no danger…In the past the Earth has gone through the tails of comets many times, and generally no one knows of it until after it had occurred, and astronomers made it known.”

The newspaper also printed the comments of French physicist and mathematician Jacques Babinet who described the head of the comet as “very small; so that even the greatest comets are insignificant bodies” except for their “immense airy tails.” Babinet contended the tail contained “no more than one particle to a cubic mile of space.” He called comets “mere airy ghosts of gaseous nature and the most harmless of celestial bodies.” He added if a comet did collide with the Earth, “the harm done would be very slight, and purely local in character. It…would not be worse than we frequently observe in the eruption of a volcano such as Vesuvius.”

The Public Gets its First View of the Comet

Halley’s came closest to the Sun on April 20th and Venturans began to spot Halley’s, first with “field glasses” and then with the naked eye. The Ventura Free Press wrote on April 22nd that clear morning skies gave Saticoy residents their first look at the comet.

With Halley’s rushing towards the Earth at a rate of three million miles a day, the national press found it to be a convenient scapegoat and blamed it for floods and extreme weather. The Oxnard Courier admitted as the comet approached, “old mother earth has been visited by some very freakish storms.” But quoted in The Ventura Weekly Post and Democrat, Columbia University professor Samuel Mitchell said, “It is an absolute certainty that the comet is as innocent as I am of the weather offenses. It can have absolutely no effect on weather conditions.”

The Ventura Free Press turned to the late western humorist Bill Nye for comfort. “If we could get close to a comet without frightening it away,” he said “we would find that we could walk through it anywhere as we could through the glare of a torchlight procession. We should so live that we will not be ashamed to look a comet in the eye, however. Let us pay up our newspaper subscription and lead such lives that when the comet strikes us, we will be ready.”

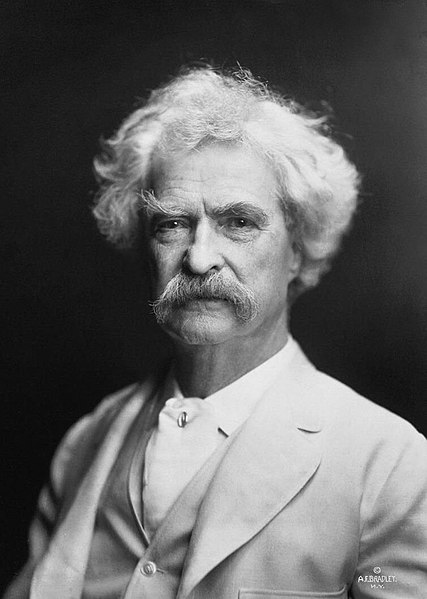

Another American writer, satirist Mark Twain was born in November 1835, two weeks after Halley’s came closest to the Sun on its last trip. In his autobiography, published in 1909, he said, “I came in with Halley’s comet in 1835. It is coming again next year, and I expect to go out with it. It will be the greatest disappointment of my life if I don’t go out with Halley’s comet. The Almighty has said, no doubt: ‘Now here are these two unaccountable freaks; they came in together, they must go out together.’” Twain’s premonition was right. He died on April 21, 1910. King Edward VII of England also died during the comet’s reappearance on May 6. Though both men were in failing health, their deaths were disquieting to the superstitious.

On the day of the King’s death, deep in the pages of The Ventura Weekly Post and Democrat was the advisory that the best time to see the comet was between 3 and 4 o’clock in the morning. The editors noted the information was “from hearsay, as we are not usually scanning the cerulean firmament at that unseasonable hour.”

On Friday May 13, just a few days before the Earth was to encounter Halley’s possibly poisonous tail, The Long Beach Telegram and The Long Beach Daily News offered these tongue-in-cheek soothing words. “Don’t cross a bridge till you come to it, and even if the comet does happen to be the bridge, how delightful it will be to cross over into the other world, not by rowing across a deep, dark river, all by one’s self, but on the tail of the comet, that glowing luminous, glorious light, with millions of one’s fellow beings to keep us company and chatter and exclaim over the beauties on the way.” The editors concluded “since the beginning of the world there have been comet scares, and weird prophesies by uncanny prophets…and the worst that has ever happened has been the terrorizing of the susceptible.”

Scientists At the Ready as Comet Approaches Earth

Halley’s became a fixture on Ventura’s east side. The Ventura Weekly Post and Democrat told readers to look “over the east end of Main Street, where it may be seen any morning after 2:30 o’clock.” The Oxnard Courier mentioned growing public interest in the comet and added, “It is a means of getting people to arise early and it certainly is worth the effort to see.”

Scientists and government agencies were preparing for the fly-by. The bulletin published by U. S. Naval Hydrographic Office asked mariners to watch for ocean disturbances from comet. The Ventura Weekly Post and Democrat editor wrote, “If Uncle Sam thinks it necessary to get excited about our visitor some of us might afford to get up a bit early to take notes. However, we prefer to do our share when the comet begins to make afternoon calls.”

Delicate electrometers and other instruments were installed at the observatory on Mt. Wilson in Los Angeles to measure electrical phenomena and the chemical nature of the gases in the tail. The Mt. Wilson scientists scoffed at the danger from cyanogen gas and didn’t even expect much of a light show, only a slight illumination due to refracted light.

With skeptical scientists ready, most of the public was prepared to put their anxiety aside and witness what, for most, would be a once in a lifetime event. The Ventura Weekly Post and Democrat described the best time to see the comet on May 19th as between 6:30 and 7:30 p.m. in the horizon slightly above where the sun set. In Camarillo about forty people gathered at the church for a social time and to watch the comet. About midnight coffee, sandwiches and cake were served. The fog came up soon afterwards and they all went home concluding that nothing could be seen if they waited. A comet party was held at the Conejo Valley’s Timber School. The Ventura Weekly Post and Democrat commented, “Talk about the Conejo not being up to date. ‘Twill be right in the front row when we are whisked out of existence by the comet, believe me.”

No Choking Gas, No One Sees Anything

On May 19, 1910, Earth passed through the end of Halley’s tail for six hours. As dawn arrived on May 20, it was like any other day. The oceans had not emptied, and people had not choked on cyanide gas. The Ventura Weekly Post and Democrat described Halley’s “passing caress” as so light and delicate that old Mother Earth kept on steadily and cheerfully revolving without acknowledging in any way that she had been hit.” People who watched from rooftops and astronomers with their telescopes concluded they hadn’t seen anything of the tail.

The Los Angeles Evening Post-Record lashed out at French astronomer Flammarion writing that people waiting “for the end of the world by the laughing gas route” were “flim-flammarioned” by a scientist with “ a wonderful imagination…He can get heat out of the center of the earth and can count the boats on the canals of Mars — in his imagination of course.”

A Relaxed Public Can Now Joke About the Comet

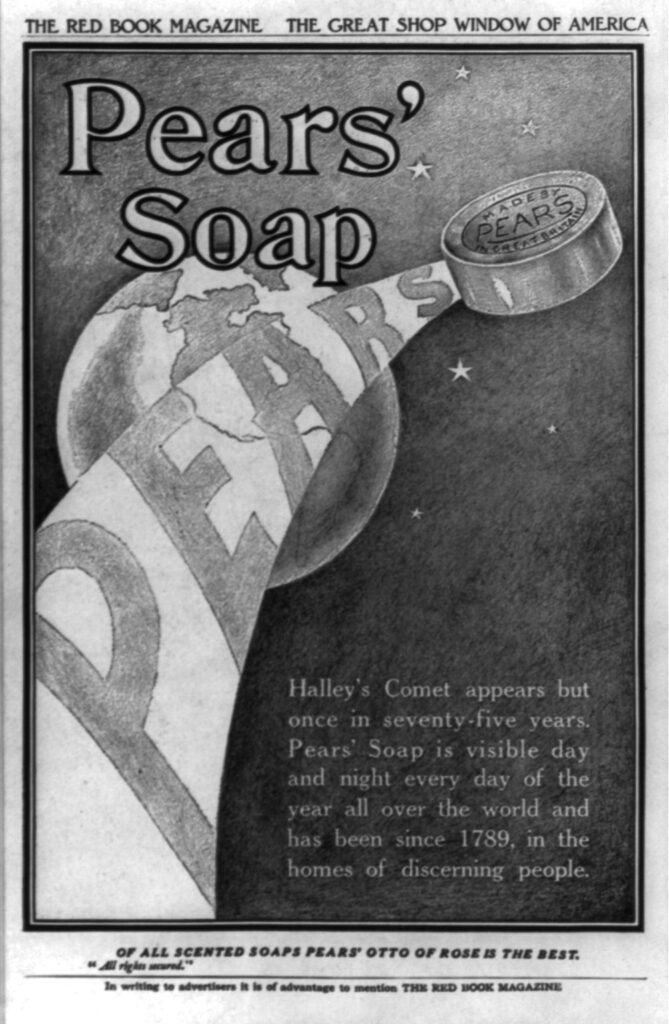

Others took a more jovial approach to the comet’s passing. Songs and poems were composed. Bird’s Custard featured a dish of its product riding on the head of the comet in its advertising while Pears’ Soap used the slogan, “Pears’ soap is visible day and night all over the world.” An Oxnard girl, Mae Bellah celebrated her 10th birthday with a comet party, highlighted with a game of “pinning the tail on the comet.”

After passing safely through Halley’s tail, the newspaper editors poked fun at the superstitious. The Ventura Free Press suggested with the comet “fast hiking away into space,” the public needed “to find something else to lay our troubles to.” When a car taking Ventura County Supervisors to Sacramento broke an axel outside of Santa Barbara, the newspaper reported the Supervisors said it must have been the fault of the comet. The editors insisted the supervisors were “too polite” to say it was due to poor Santa Barbara County roads.

When the Free Press editors wrote about the strength of Republican gubernatorial candidate Hiram Johnson, they pointed out that “Johnson is well in lead of all the Republican candidates at this writing and gaining strength so rapidly that it will take “more than a brush with a comet to wipe away enough of his strength” to bring the other candidates even within shouting distance. Johnson was elected as California’s 23rd governor on November 8, 1910.

But there still was an appetite for stories suggesting the comet had ominous powers. The Ventura Weekly Post and Democrat printed the tale told by Arizona man, L. B. Cannon. On May 9th, Cannon was in the desert about 80 miles northwest of Phoenix. He saw a small, reddish-colored, swirling cloud of dust. He rode his horse into the cloud, but had to retreat immediately as both he and his horse began “coughing severely.” Cannon said there was a sulfurous smell and the dust smarted when it landed on his skin. When the dust had settled, he rode back to find the bushes and ground covered with the reddish powder and several rabbits and birds dead and still warm. They had been overcome by the air-borne poison that Cannon insisted could only have come from the comet.

Special View of the Comet During Total Eclipse

Halley’s had one last show in store. Venturans gathered on their doorsteps or in their yards for evening “rubber neck” parties on May 26th when between 8 and 10 o’clock there was a total eclipse of the Moon. The Ventura Weekly Post and Democrat described the moment when the Earth’s shadow covered the Moon as the “blackness of the heavens added to the brilliancy of Halley’s famed protege. The view afforded of the phenomenon was remarkable, and the like will probably not again be witnessed in a lifetime.”

As the comet continued its path away from the Earth, the Ventura Free Press editor wondered “if some of the newspaper articles which have been read with such interest will be placed away in some nook or corner and be unearthed by some of us 75 years hence when the famous Halley’s comet again makes his appearance.”

A Handful of “Two-Timers” Get a Second Look at Halley’s

Right on schedule, Halley’s did return in February of1986. It was a bit of a disappointment. The comet and the Earth were on opposite sides of the Sun, creating the worst possible conditions for Earth observers in 2,000 years. There were plans to observe Halley’s from low earth orbit on two Space Shuttle missions. Tragically, the mission to record the ultraviolet spectrum of the comet ended in disaster when the Space Shuttle Challenger exploded shortly after liftoff. The second mission aboard the Columbia was cancelled after the Challenger disaster and would not fly until late 1990 after the comet was long gone.

Ninety people boarded two buses provided by Ventura’s Lambert’s Tours and Travel and went to the Griffith Observatory to see the comet in 1986. Several of the passengers on the buses to Los Angeles were “two-timers,” who would see Halley’s twice in their lifetime. Guy Austin of Ventura was 82 and said he was disappointed with the view. He said it wasn’t as bright as he remembered it as a 6-year-old. Another Venturan, 87-year-old Willard Smith remembered his family was scared in 1910. His second view of the comet was far from frightening, “It looked like a hunk of epoxy glue.” Edith Cruden of Camarillo was also not impressed, “It looks like a fuzzy, dirty snowball.” The visit did have a highlight for 85-year-old Celia Temple of Ventura. She was sitting on a bench outside the observatory looking at the certificate she was given as a “two-timer.” She said, “Two little girls came up to me and asked if I really had seen the comet before and were quite impressed. One even told me I looked only 65.”

Halley’s next visit to the Earth is predicted for July 28, 2061. The comet’s solitary journeys through the solar system and past the Sun take a toll. Halley’s nucleus loses mass on each revolution and will most likely disappear after another 2,300 trips or 175,000 years.

Make History!

Support The Museum of Ventura County!

Membership

Join the Museum and you, your family, and guests will enjoy all the special benefits that make being a member of the Museum of Ventura County so worthwhile.

Support

Your donation will help support our online initiatives, keep exhibitions open and evolving, protect collections, and support education programs.

Bibliography

- “Apocalypse postponed: how Earth survived Halley’s comet in 1910.” The Guardian. Last modified December 20, 2012. https://www.theguardian.com/science/across-the-universe/2012/dec/20/apocalypse-postponed-halley-comet#:~:text=The%20technique%20of%20spectroscopy%2C%20in,poison%2C%20in%20the%20comet’s%20tail.

- “Bill Nye, Frontier Humorist.” WyoHistory.org | The Online Encyclopedia of Wyoming History. Accessed November 12, 2024. https://www.wyohistory.org/encyclopedia/bill-nye-frontier-humorist.

- Camarillo Star. “Comet Watcher Relies on Experience.” February 13, 1986, 6.

- Campbell, Frederic C. “Halley’s Comet.” Ventura Free Press, May 13, 1910, 8.

- Campbell, Frederic C. “Halley’s Comet.” Ventura Free Press, April 15, 1910, 8.

- Campbell, Frederic C. “Halley’s Comet.” Ventura Free Press, April 22, 1910, 8.

- Campbell, Frederic C. “Halley’s Comet.” Ventura Free Press, April 29, 1910, 8.

- Campbell, Frederic C. “Halley’s Comet.” Ventura Free Press, May 6, 1910, 8.

- “Comet Fever: 1910.” Grinnell Stories. Accessed November 12, 2024. https://grinnellstories.blogspot.com/2019/05/comet-fever-1910.html.

- “Cyanogen: a Poison, a Comet and a Jedi Story.” Department of Molecular Astrophysics – ASTROMOL. Last modified July 21, 2015. https://astrochem.iff.csic.es/2015/07/21/cyanogen-a-poison-a-comet-and-a-jedi-story/.

- Frost, Asmund. “When Comet Halley Was About to Cover Earth in Cyanide Gas.” Medium. Last modified April 8, 2022. https://medium.com/predict/when-comet-halley-was-about-to-cover-earth-in-cyanide-gas-494b8daee26e.

- Goodrich, Richard J. Comet Madness: How the 1910 Return of Halley’s Comet (Almost) Destroyed Civilization. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield, 2023.

- “Halley’s Comet.” Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia. Last modified November 12, 2024. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Halley%27s_Comet.

- “Halley’s Comet 100 Years Ago.” The Denver Post. Last modified May 25, 2010. https://www.denverpost.com/2010/05/25/halleys-comet-100-years-ago/.

- “Humanities Catastrophic Test: How Halley’s Comet Reappearance Stirred the World.” The Epoch Times. Last modified April 12, 2023. https://www.theepochtimes.com/bright/scientists-charlatans-and-halleys-comet-5132764?welcomeuser=1.

- The Long Beach Telegram and The Long Beach Daily News. “Friday, the Thirteenth.” May 13, 1910, 5.

- Los Angeles Evening Post-Record. “In the Public Eye.” May 30, 1910, 7.

- Los Angeles Evening Post-Record. “It’s Mighty Little Wisest Men Know About Comets.” April 2, 1910, 4.

- Los Angeles Evening Post-Record. “Ready to Watch Comet From Mt. Wilson.” May 17, 1910, 1.

- Morning Free Press (Ventura). “Closer to Earth Than Any Other Known Body in Universe Except the Moon.” January 31, 1910, 4.

- Morning Free Press (Ventura). “Comet Appears to Ventura Gazers.” January 24, 1910, 1.

- Morning Free Press (Ventura). “Comet Seen in the Morning.” January 25, 1910, 1.

- Morning Free Press (Ventura). “Comet to Do Split.” January 28, 1910, 1.

- Morning Free Press (Ventura). “Draws Line at Swiping Big Comet.” January 7, 1910, 1.

- Morning Free Press (Ventura). “Halley’s Comet Has A Tail.” January 12, 1910, 1.

- Morning Free Press (Ventura). “Halley’s Comet Nearest In May.” January 31, 1910, 1.

- Morning Free Press (Ventura). “Halley’s Comet Will Hit Us.” May 8, 1910, 1.

- Morning Free Press (Ventura). “Look Out for Halley’s Comet on February 1.” January 20, 1910, 1.

- Morning Free Press (Ventura). “Venturans See The New Comet.” January 26, 1910, 1.

- The New York Times. “Comet’s Poisonous Tail.” February 8, 1910, 1.

- Oxnard Courier. “Camarillo Items.” May 20, 1910, 7.

- Oxnard Courier. “Comet Party Enjoyed by Little Folks.” June 24, 1910, 5.

- Oxnard Courier. “Comet Searches Western Horizon and Then Disappears.” January 28, 1910, 1.

- Oxnard Courier. “Comet View By Many Last Night.” May 27, 1910, 1.

- Oxnard Courier. “Editorial.” April 29, 1910, 5.

- Oxnard Courier. “Newsletter from Camarillo Section.” May 13, 1910, 2.

- “The Panic of Halley’s Comet in 1910.” Facts-Chology. Last modified January 16, 2023. https://factschology.com/factschology-articles-podcast/halleys-comet-panic-1910#google_vignette.

- Progress-Bulletin (Pomona, California). “Will Halley’s Comet Kill Us All.” February 8, 1910, 1.

- “REVIEW: Comet Madness.” Meaghan Walsh Gerard – Writer. Photographer. Woman of Letters. Accessed November 12, 2024. https://www.mwgerard.com/review-comet-madness/.

- Simi Valley Star. “Glimpse of Comet in 1910 Was Enough.” January 19, 1986, 2.

- Simon, Matt. “Fantastically Wrong: That Time People Thought a Comet Would Gas Us All to Death.” Wired. Last modified January 7, 2015. https://www.wired.com/2015/01/fantastically-wrong-halleys-comet/.

- “The Space Review: Review: Comet Madness.” The Space Review: Essays and Commentary About the Final Frontier. Accessed November 12, 2024. https://thespacereview.com/article/4553/1.

- The Ventura Weekly Post and Democrat. “Harmlessness of the Comet’s Tail.” February 25, 1910, 2.

- “Through the Comet’s Tail.” Ian Ridpath: Astronomy Writer, Broadcaster, Lecturer. Accessed November 12, 2024. https://www.ianridpath.com/halley/halley12.html.

- Ventura County Star. “For Some, Second Look at Halley’s is Not So Hot.” January 12, 1986, 35.

- Ventura Free Press. “Claim That Comet Influences Wine Crop.” March 4, 1910, 5.

- Ventura Free Press. “Comet Shines While Moon Is Eclipsed.” May 27, 1910, 1.

- Ventura Free Press. “County News Told By Our Correspondents.” May 13, 1910, 6.

- Ventura Free Press. “Editorial.” May 20, 1910, 4.

- Ventura Free Press. “Happenings of a Week in the City and County.” April 22, 1910, 5.

- Ventura Free Press. “Look Them In the Eye.” April 22, 1910, 4.

- Ventura Free Press. “Newsy Notes From Saticoy.” April 22, 1910, 6.

- Ventura Free Press. “Saticoy People and Their Doings.” May 27, 1910, 6.

- Ventura Free Press. “Secures Fine Articles.” April 15, 1910, 5.

- Ventura Free Press. “Suburbanites and Their Doings.” February 11, 1910, 6.

- Ventura Free Press. “Supervisors Are Stalled En Route.” May 20, 1910, 3.

- Ventura Free Press. “They Are On Their Way.” May 20, 1910, 2.

- Ventura Free Press. “Venturans See the New Comet.” January 28, 1910, 2.

- The Ventura Weekly Post and Democrat. “Bill Nye Discusses the Comet Question.” May 20, 1910, 4.

- The Ventura Weekly Post and Democrat. “Comet Bids Adieu to Morning Skies.” May 20, 1910, 2.

- The Ventura Weekly Post and Democrat. “Comet Not Responsible for Weather Freaks.” April 29, 1910, 3.

- The Ventura Weekly Post and Democrat. “Comet and Moon Act According to Program.” May 27, 1910, 8.

- The Ventura Weekly Post and Democrat. “Editor’s Comments.” May 13, 1910, 2.

- The Ventura Weekly Post and Democrat. “Halley’s Comet Appears in “Twilight Time”.” March 18, 1910, 8.

- The Ventura Weekly Post and Democrat. “Information About Straggling Comet.” January 28, 1910, 2.

- The Ventura Weekly Post and Democrat. “Information About Straggling Comet.” January 28, 1910, 2.

- The Ventura Weekly Post and Democrat. “Its Tail Threatened.” February 4, 1910, 7.

- The Ventura Weekly Post and Democrat. “Not An Earth Smasher.” February 25, 1910, 4.

- The Ventura Weekly Post and Democrat. “Of Local Interest.” January 28, 1910, 9.

- The Ventura Weekly Post and Democrat. “Of Local Interest.” May 20, 1910, 7.

- The Ventura Weekly Post and Democrat. “Of Local Interest.” May 6, 1910, 7.

- The Ventura Weekly Post and Democrat. “Part of Lost Tail is Heard From.” May 27, 1910, 4.

- The Ventura Weekly Post and Democrat. “Say Halley’s Comet Will Be Harmless.” April 15, 1910, 6.

- The Ventura Weekly Post and Democrat. “Sufficiently Near to be Local Feature.” April 13, 1910, 6.

- The Ventura Weekly Post and Democrat. “Supervisors Meet With Mishap.” May 20, 1910, 5.

- The Ventura Weekly Post and Democrat. “The Latest in Comet Movements.” February 11, 1901, 2.

- The Ventura Weekly Post and Democrat. “What We Know About Comets.” April 22, 1910, 6.

- “What Was the Halley Comet Panic of 1910?” TheCollector. Last modified August 19, 2024. https://www.thecollector.com/halley-comet-panic-1910/.