by Library Volunteer Andy Ludlum

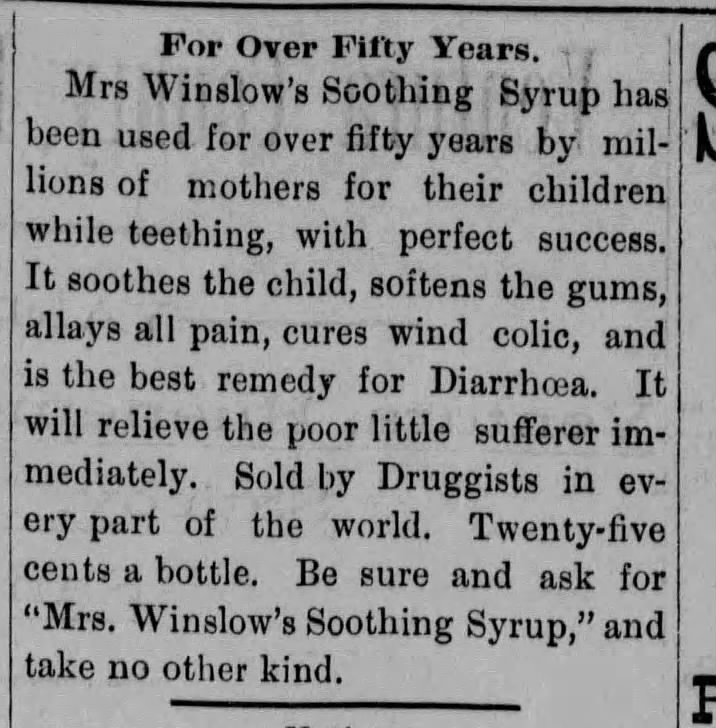

When a baby was teething and wouldn’t stop crying, there’s a good chance that Ventura County parents in the late 1800s reached for “Mrs. Winslow’s Soothing Syrup.” The medicine was produced for years. The makers promised it was “likely to soothe any human or animal,” and could quiet restless babies and small children. Victorian-era parents knew the syrup would finally get their baby to go to sleep. What they may not have known was how much morphine was in this “indispensable” product. One teaspoon of the syrup contained ten times the amount of the drug recommended for a 6-month-old baby. And if the morphine was not enough, the other active ingredient in “Mrs. Winslow’s Soothing Syrup” was alcohol.

Overuse by some parents led to child deaths. In 1911, a section in the American Medical Association publication Nostrums And Quackery called “Baby Killers” singled out Mrs. Winslow’s Soothing Syrup as a dangerous product. Despite the condemnation, the product was not withdrawn from sale for another 20 years.

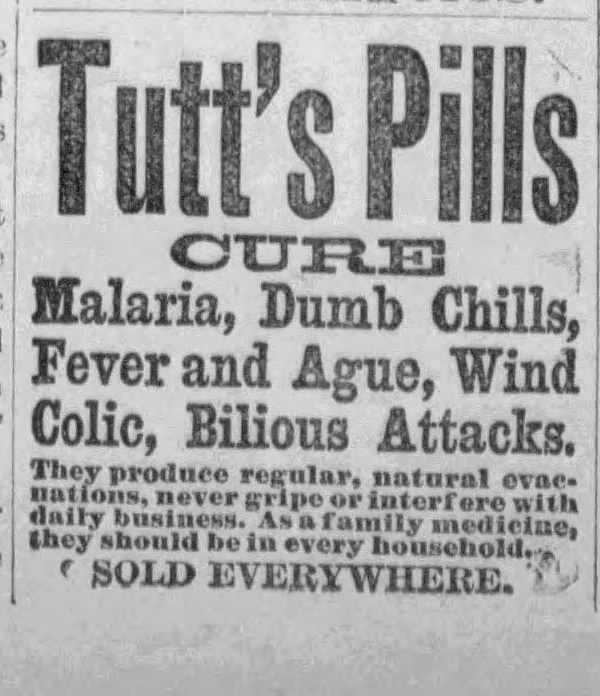

“Mrs. Winslow’s Soothing Syrup” is an example of easily accessible, over-the-counter remedies called “patent medicines.” These popular remedies were often laced with alcohol and contained dangerous levels of opium and other potentially addictive narcotics. Some of the medicines included toxic ingredients such as lead and mercury.

The drugs were aggressively advertised to the public in an era before drug regulation. While makers often touted their products as panaceas and cure-alls, it was rare for any of the patent medicines to deliver the curative powers promised in their exaggerated advertising.

Most Patent Medicine Wasn’t Patented

Patent medicines were most popular from the mid-19th century to the early 20th century. They date back to 17th century England when the inventors of unique remedies were granted “letters patent” by the Crown, giving the makers a monopoly over their formulas. While the colorful names of the drugs were trademarked, for the most part, the medicines purchased in Ventura County were not patented so their formulas would remain secret.

The Appeal of Patent Medicine

When Ventura County was formed in 1873, it had a population of about 3,500 residents. Most were farmers who cultivated hay, citrus fruits, grapes, and beans. Ventura County was like most of America; three out of four people lived on farms or in rural communities.

When these early farmers became sick, they were usually treated at home by someone they knew, not necessarily a trained doctor. Trained doctors were somewhat scarce in the 1800s and one of the county’s first was Cephas Little Bard, M.D., who began practice in the county in 1868. Dr. Bard did not hold his predecessors in high esteem – Bard would later say the county’s early physicians “were very poor,” and added that most “with hardly an exception, were grossly incompetent and in no respect prepared for the exigencies and emergencies of the service.”

Unless there were alarming symptoms or a severe injury, a family member might first be consulted, then a neighbor and finally perhaps a druggist before a doctor was called. Pharmacists in small towns were often “one-stop shopping” for a wide variety of medical needs. An 1880 ad for Delmont’s Drug Store on Main Street in Ventura touts that Dr. F. Delmont “keeps constantly on hand a full assortment of drugs and patent medicines.” Some doctors went into business with the pharmacists. In 1886 the Ventura Weekly Post and Democrat reported that “our genial neighbor and friend Summer Sheppard” has gone into the drug business in Hueneme with Dr. O.V. Sessions, who at the time was Hueneme’s only doctor. The paper added, “We have a high opinion of the doctor both as a citizen and physician and wish the new firm the utmost prosperity.”

While very few women practiced medicine in the late 19th century, the role of “healer” in the household belonged to women. Many women kept books of recipes to treat everything from croup to rheumatism. A bookseller’s ad in the Ventura Free Press in 1886 offered The Home Cookbook and Family Physician, containing simple home remedies to “cure all common ailments.” Many wives and mothers used herbs like lavender, rosemary, wormwood, sage, foxglove, and mint to create herbal medicines to cure family members of headaches, stomach pains, and even more serious conditions such as heart, liver, and kidney ailments.

Herbal medicines were widely used by doctors. Dr. Bard, who practiced until his death in 1902, admired the medicinal use of spring water, herbs, and plants by the Chumash and said, “no one is so close to nature.” The Chumash used dozens of plants and naturally occurring substances from sulfur to the tar that washed ashore to treat many illnesses.

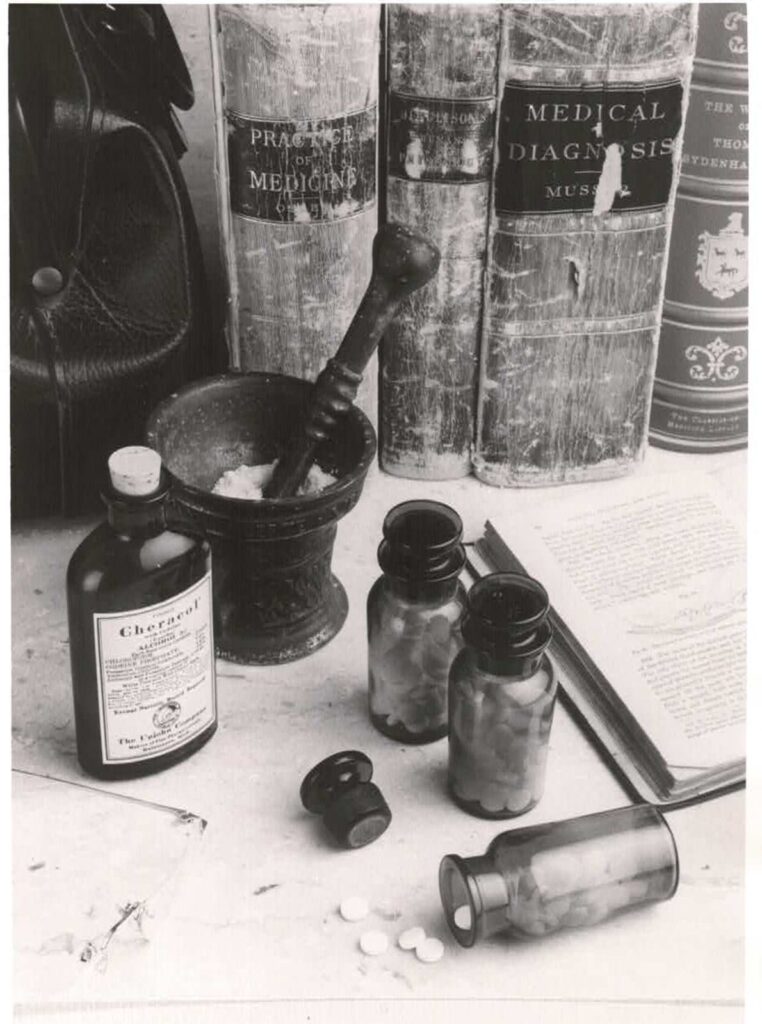

Most of the time, doctors traveled to patients’ homes with a bag filled with drugs: pills, salves, powders and in some cases, a harmless placebo, sugar pills. Some doctors complained patients demanded a prescription as proof something was being done for them. No distinction was made between prescription and over-the-counter remedies. Patients could dose themselves with whatever they could afford, including opiates.

People believed in most cases, that a patient could be expected to recover, with or without the help of a doctor. The Ventura Free Press reported gleefully in 1893, “We are glad to say that Somis is such a healthy place, that a doctor cannot be supported here. Dr. Glass left here for Simi, Monday, where those wishing to see him can find him hereafter.”

Ventura was unique for its size. It opened a hospital in 1887 when they were still considered a big-city phenomenon. But many in the late 19th century thought of hospitals as a place to die and so avoided them.

Doctors were grudgingly appreciated. The Ventura Free Press editors in 1881, complaining about murder convictions being reversed by the California Supreme Court wrote, “It is almost a miracle that any judgements are affirmed, for lawyers, like doctors, seldom think alike.” The same newspaper, five years later, described an Inuit custom in Alaska. “At each visit the doctor is paid. If the patient recovers, the physician keeps the money; if the patient dies the money is returned to the family of the deceased.”

Pioneers of Deceptive Advertising

The second half of the 19th century was the golden age of patent medicines. Medicine makers reached nearly everyone through newspaper advertising and their messages were free from scrutiny or regulation. There were thousands of ads in Ventura County newspapers. Readers were exposed to national campaigns hawking miraculous cures for a surprising array of illnesses. To modern eyes, some look like typical newspaper ads, while others appear to be news stories, indistinguishable from the editorial copy on the page.

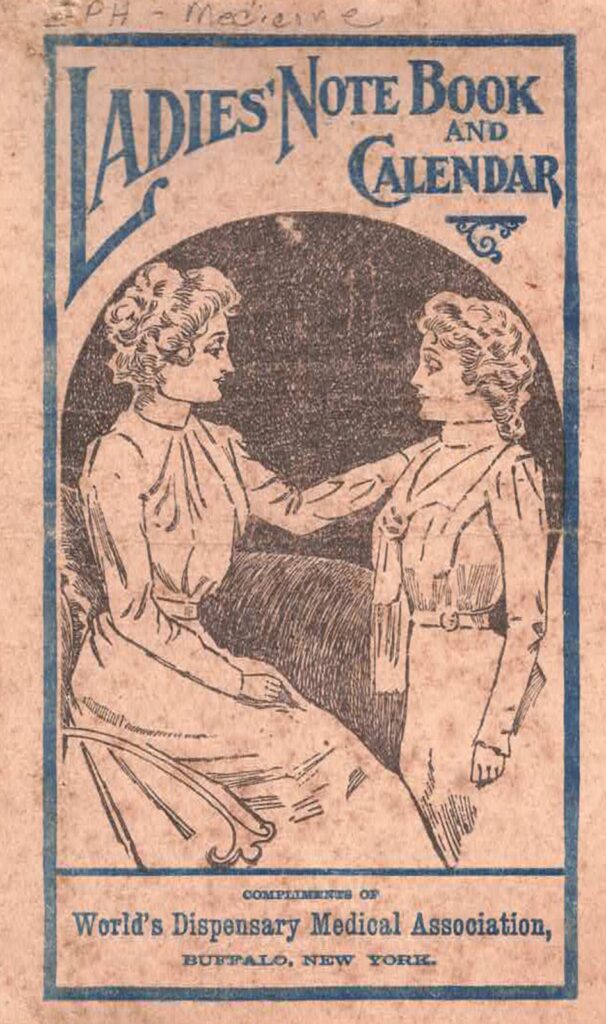

Many of these outlandish ads contained testimonials from users and endorsements from experts and celebrities. The miracle cures were also promoted with an ample supply of posters, trade cards, almanacs, recipe books, calendars, and other freebies.

And there were traveling medicine shows. A showman, often called “doctor” or “professor,” would lure in a crowd with circus-like entertainment to pitch his cures. These shows were big community events and often performed several times a day or on multiple days of the week. The Ventura Weekly Post and Democrat noted in February 1894 that “a free medicine show has been the order of the week, at Union Hall.”

Potent and Addictive Painkillers

Just as it is today, a common medical complaint in 19th century Ventura County was pain. New techniques had led to the development of potent pain medications derived from opium, including morphine, codeine, and heroin. The pain killers were put to extensive use during the Civil War. The Union Army issued nearly 10 million opium pills, plus almost 3 million ounces of opium powders and tinctures.

Doctors saw opioids as all-purpose drugs and prescribed them liberally for everything from coughing to diarrhea. In 1891, the Ventura Free Press reported a doctor, identified as “Dr. Marks,” displayed an ounce of crude opium which he had gathered from the hospital garden “while the poppies were in condition.” The newspaper added Dr. Marks “thinks the business could be made to pay.”

Pharmacists sold opioids as over-the-counter drugs. By 1895, morphine and opium powders had led to an addiction epidemic that affected roughly one in 200 Americans. The typical opiate addict at the time was an upper-class or middle-class white woman.

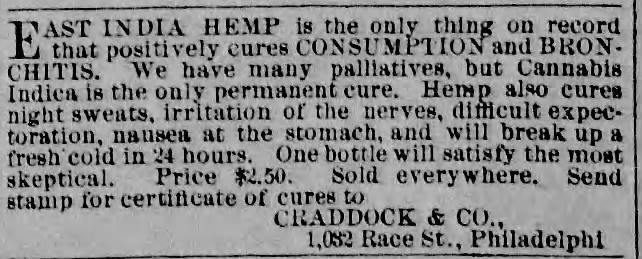

In 1891 the Ventura Weekly Post and Democrat advertised the “East India Cure” which it said would be a “sure cure” for liquor and opium habits and could “be given without the patient’s knowledge.”

New regulations passed between 1895 and 1915 restricted the sale of opiates to patients with a valid prescription. While doctors were aware of the dangers of drug addiction, they had few alternatives to offer their patients.

Some makers took advantage of the public’s increasing awareness of drug addiction. The laxative “Fletcher’s Castoria” was the subject of one of the most significant campaigns in early mass advertising. Castoria ads were common in Ventura County newspapers for decades including a 1907 ad in the Ventura Weekly Post and Democrat which noted the product was an effective “harmless substitute” for soothing syrups and other products containing opium, morphine, and other narcotics. Castoria contained senna, sodium bicarbonate, essence of wintergreen, dandelion, sugar, and water.

Cocaine was another potent pain medication developed during this era. Derived from coca leaves, cocaine was especially prized for relieving toothaches.The Ventura Weekly Post and Democrat, after it ran an article in 1885 about a doctor who was driven to insanity by his excessive use of cocaine, felt obligated to offer a “timely vindication of cocaine.” The paper quoted an “eminent” but unnamed Chicago doctor who insisted there is no such thing as a “cocaine habit.” The doctor claimed to have used cocaine with hundreds of patients without any bad effects. To prove the drug was safe, he used it on himself. He took increasing doses over a two-month period, monitoring its effect. He built up to taking 25 grains of cocaine in a 24-hour period. The doctor said he “failed to form a cocaine habit and proved to [him]self that the drug is not one which enslaves.”

Alcohol was a common, if not the main, ingredient in many patent medicines.“Chamberlain’s Cough Remedy” packed an alcoholic punch.A 1904 Ventura Free Press ad was directed towards mothers of small children. It said,“When you buy…cough medicine for small children you want one in which you can place implicit confidence. You want one that not only relieves but cures. You want one that is unquestionably harmless.”

Other alcohol rich products included bitters. “Hostetter’s Stomach Bitters” was sold as a medicinal tonic. One 1900 Ventura Free Press ad recounted the biblical predictions of a “famous scientist” who believed that the world would come to end in 1914. The ad continued, “it is well for us to get what pleasure we can out of the few years that remain for us to live. One of the surest ways to enjoy life is the possession of good health and a well-regulated stomach.” The product was offered as a cure-all for “dyspepsia, constipation, fever and ague, malaria, rheumatism and insomnia.” The company insisted its secret herbal formula was most effectively delivered by its 47% alcohol content.

That the medicines contained alcohol was no secret. During the Prohibition era, the Moorpark Enterprise criticized “overzealous police” when they came up empty-handed in a 1924 search for illegal liquor at an Oxnard drug store and found “nothing stronger than Mrs. Winslow’s soothing syrup.”

There were several therapeutic oils purported to combat pain. “Dr. Thomas’ Electric Oil” was touted as the “monarch over pain” and promised to stop earache pain in two minutes, toothache or minor burn pain in five minutes, muscle aches in two hours, and sore throats in 12 hours. The oil was concocted by New York doctor Samuel Thomas, known as the “electric physician.” Electricity was marketed as a miracle cure in the late 1800’s and early 1900’s. The product name was changed to “Eclectric Oil,” a portmanteau of “eclectic” and “electric” when the 1906 Pure Food and Drug Act prohibited misleading information on product labels. In this case, electricity was not among the ingredients. “Dr. Thomas’ Eclectric Oil” contained common ingredients such as turpentine, camphor oil (the smell in vapor rub), eucalyptus, thyme, and a variety of fish oils.

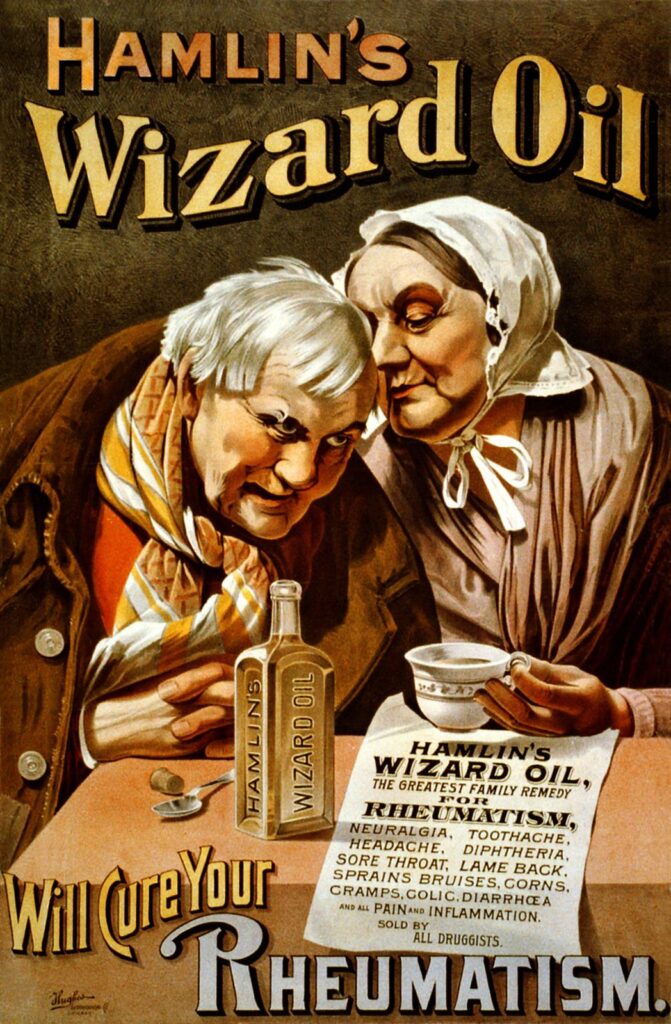

“Hamlin’s Wizard Oil” promised “wonderful healing power” for rheumatism, neuralgia, toothache, headache, earache, croup, sore throat, lame backs, and stiff joints in an 1887 Ventura Free Press ad. It was made of 70% alcohol and contained camphor, ammonia, chloroform, sassafras, cloves, and turpentine. It was said to be usable both internally and topically.

While the exact ingredients of “Chamberlain’s Pain Balm” have been lost over time, it’s likely the cure-all also made liberal use of alcohol. An 1894 Ventura Free Press ad noted “no medicine [was] so often needed in every home” to quiet rheumatism or neuralgia. A 50-cent bottle could be used to “promptly relieve” the pain of cuts, burns, scalds, and sprains. “Chamberlain’s Pain Balm” was said to be equally effective on sore throats, lame backs, and troublesome corns. The bottle label also suggested the balm was effective for raw sores on horses.

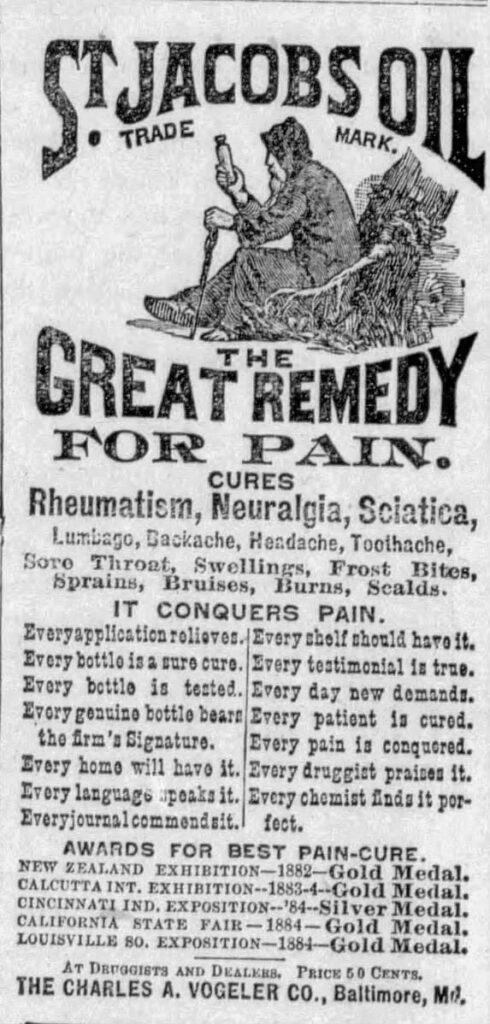

The liniment “St. Jacob’s Oil” was a remedy created by German immigrant August Vogeler. An 1887 ad in the Ventura Free Press called it the “great remedy for pain” and promised cures for rheumatism, neuralgia, and sciatica along with minor aches and pains. The liniment was primarily a turpentine, ether, and alcohol mixture. Capsicum from cayenne peppers was also added which probably made the liniment act like today’s icy-hot rubs. After 1913 chloroform was added as a replacement for the ether.

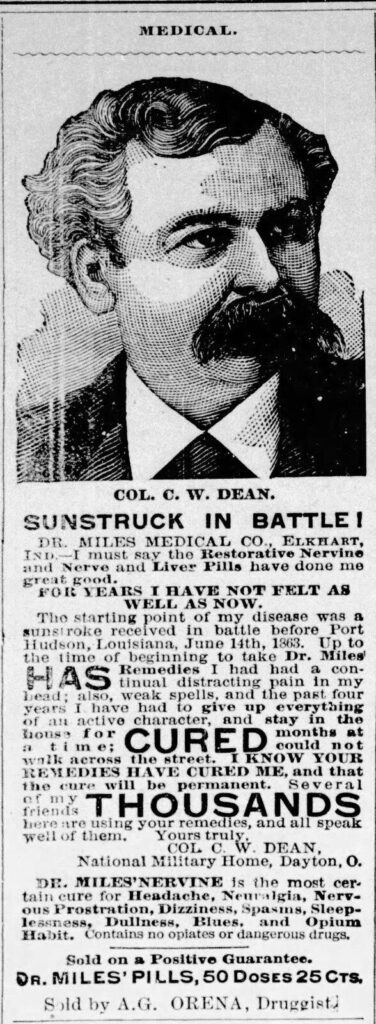

Dr. Miles’ Nervine” was said to treat “nervous” conditions, including nervous exhaustion, sleeplessness, hysteria, headache, neuralgia, backache, pain, epilepsy, and spasms. Frankin Miles was an Indiana eye and ear specialist interested in the nervous system’s connection to overall health. An 1894 ad in the Ventura Weekly Post and Democrat featured the testimonial of Colonel C.W. Dean who had been in constant pain since suffering sunstroke before an 1863 battle. The doctor’s Nervine had cured him and he was enjoying retirement in an Ohio military home.

Thirteen years later, another ad complained that “unscrupulous persons are making false statements” about Miles’ remedies and offered a $5,000 reward to “any person who can find one atom of opium chloral, morphine, cocaine, ether, chloroform, heroin, alpha and beta eucaine, cannabis indica or chloral hydrate or any of their derivatives in any of Dr Miles’ Remedies.” The active ingredient in Nervine was bromide, which was used in over-the-counter products such as Bromo-Seltzer until 1975. Bromide fell out of favor when it was determined as many as 10% of admissions to mental hospitals were caused by chronic bromide intoxication.

Cough Medicine With a Punch

One of the earliest and most prolific producers of patent medicines was James Cook Ayer. In 1838, Ayer worked in a Lowell, Massachusetts apothecary shop. While his boss was on vacation in Europe, he mixed up his first product, a cherry-flavored cough medicine known as “Cherry Pectoral.” Ayer quickly learned the business and bought the drugstore. He created a line of medicines including a strong laxative called “Cathartic Pills,” a blood medicine called “Sarsaparilla,” and a hair restorer called “Hair Vigor.” Ayer eventually owned multiple stores and from a state-of-the-art factory in Lowell, his 150 employees produced vast quantities of medicine that made him an estimated $20 million. Ayer died in 1878, though his products were produced until the 1940s.

While Ayer’s medicines were prescribed by doctors, his success was largely due to the huge sums he spent on advertising. Ayer’s products were pitched for decades in the Ventura Free Press and the Ventura Weekly Post and Democrat. He also distributed millions of free copies of an almanac which interspersed commentary on his products with pages of astrological information, moon phases, times of sunrise and sunset, religious notations, and even unusual facts and humorous anecdotes. The Museum of Ventura County has two of these almanacs in its collection from 1863 and 1865.

While Ayer’s medicines were extremely popular, they wouldn’t pass today’s safety standards. A 1905 ad in the Ventura Weekly Post and Democrat boldly stated, “you can hardly find a home without its Ayer’s Cherry Pectoral.” It added, “Parents know what it does for children: breaks up a cold in a single night, wards off bronchitis, prevents pneumonia.” Ayer’s pectoral probably worked, because mixed in with herbs was a good shot of alcohol and three grains of morphine. (Three grains of morphine would be equal to 194 milligrams. For moderate to severe pain, it is recommended adults be prescribed 10-20 milligrams every four hours as needed.)

Another popular product, “Sarsaparilla” was probably harmless, but lacked any medical benefits. An 1893 ad in the Ventura Weekly Post and Democrat promised it would cure a wide array of “Scrofulous Diseases, Eruptions, Boils, Eczema, Liver and Kidney Diseases, Dyspepsia, Rheumatism, and Catarrh.” Other ads urged consumers suffering from “impure blood, thin blood, debility, nervousness, [or] exhaustion” to trust the brand “you have known all your life.”

One of his most famous products was a hair dressing known as “Ayer’s Hair Vigor.” It promised to restore gray hair to its natural vitality and color. An 1887 Ventura Free Press ad made the fanciful claim it was “not a dye, but by healthful stimulation of the roots and color glands [it] speedily restores to its original color hair that was turning gray.” Despite claims to the contrary, “Ayer’s Hair Vigor” was a colorant and contained a significant amount of lead. A competitor, “Hall’s Hair Renewer” was worse. An 1870 analysis of the preparation found it contained almost three grams of lead per fluid ounce. Ayer bought out Hall in 1870.

Decades of Legal Battles Over Secret Ingredients

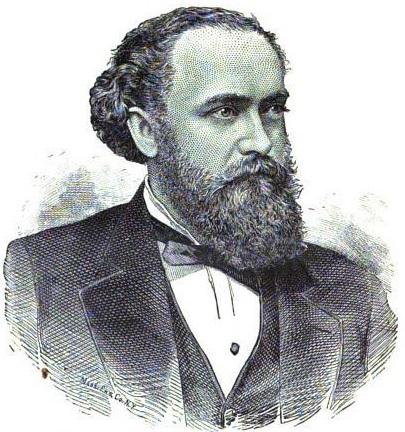

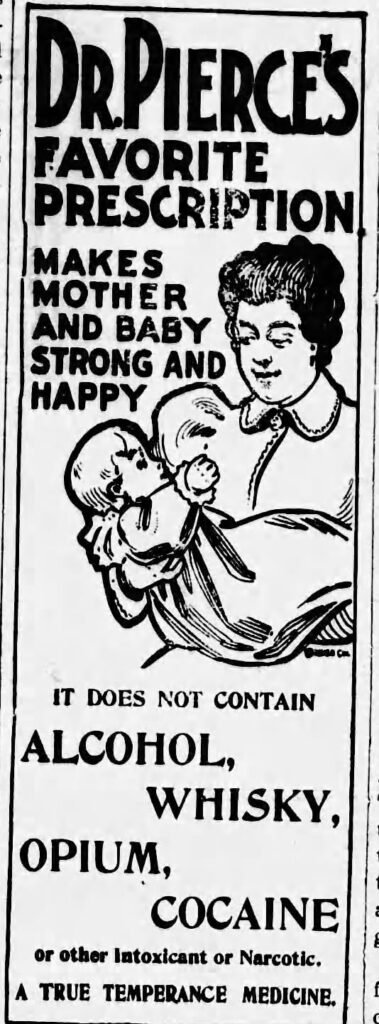

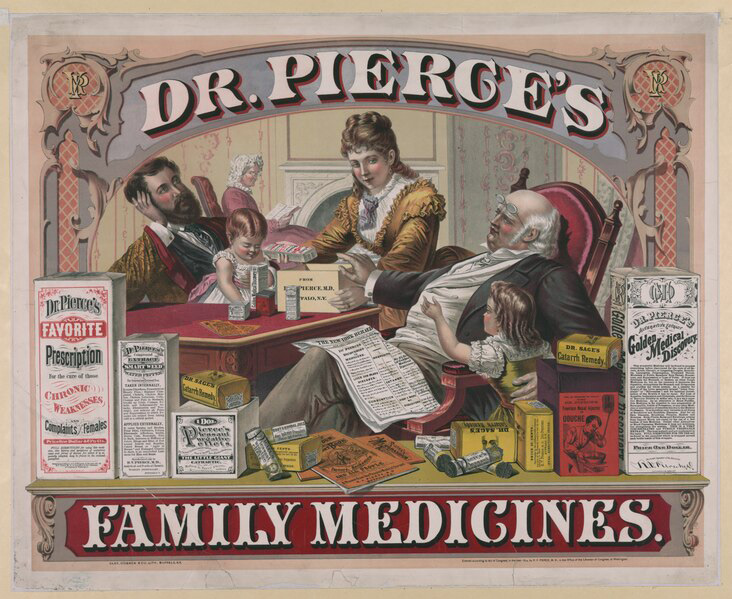

Dr. Ray Vaughn Pierce produced millions of dollars’ worth of patent medicines starting with the “Golden Medical Discovery” which he sold out of a wagon. As sales built, in 1867 Pierce moved his business to Buffalo, New York from where he began to advertise a large family of products. The licorice-flavored “Golden Medical Discovery,” reportedly contained quinine, opium, and alcohol and was advertised as giving men “an appetite like a cowboy’s and the digestion of an ostrich.”

When the “Golden Medical Discovery” was advertised in the Ventura Signal in 1875, Pierce made the bold claim that his tonic was a “blood cleanser” that could cure all forms of blood disease except cancer. Pierce used an Old Testament quote about “the blood is the life” (Deuteronomy 12:23) to support his contention that the blood is the source “from which we derive our mental as well as physical capabilities” and that it “should be kept pure.” Pierce promised relief from a wide range of skin diseases, from blotches to pimples to more serious glandular diseases.

In the early 1880’s the formulas were published for two of his medicines, “Pierce’s Golden Medical Discovery” and “Pierce’s Favorite Prescription,” and revealed that they contained opium and alcohol. Pierce fiercely denied the accusations, usually through ads with “sworn statements to the contrary.”

As early as 1876, Pierce promoted his cathartic “Dr. Pierce’s Pleasant Purgative Pellets” as being free of the dangerous chemical calomel, a form of mercury that was often found in laxatives of the time. Calomel treatment could leave a patient incapacitated for days. In a Ventura Signal ad, Pierce offered a $500 reward to anyone who could find “calomel or other form of mercury, mineral poison, or Injurious drugs” in his vegetable-based product. A modern examination of the pellets found their active ingredient was stramonium, or Jimson weed, a wild-growing plant of the nightshade family. Jimson weed contains toxic alkaloids that can be lethal in high doses.

Other medicine makers also marketed their products as an alternative to calomel. Dr. Charles Simmons believed indigestion, stomach pain, and constipation were caused by “a disarranged state of the liver.” He offered a “purely vegetable” product called “Simmons Liver Regulator.” An 1886 ad in the Ventura Free Press was headlined, “How to be Rid of Calomel.” Dr. Simmons’ “Great Regulator” was made from milk thistle, a flowering herb related to the daisy and ragweed family that has been traditionally used for liver and gall bladder problems. There is conflicting and inconclusive evidence of the benefits of milk thistle for liver health.

The ingredient controversy would haunt Pierce for two decades. In 1905, Edward W. Bok, the editor of the Ladies Home Journal, published an analysis of “Pierce’s Favorite Prescription” by a German chemist who concluded the drug contained the potentially harmful ingredients. Pierce sued. At the trial he produced three leading chemists who testified that “no digitalis, opium or alcohol is contained in Dr. Pierce’s Prescription.” Editor Bok admitted his German chemist’s tests had been done 25 years earlier and he was forced to issue a retraction.

But not everyone considered Pierce vindicated. The Editorial Board of a publication called The Medico-Pharmaceutical Critic & Guide wrote: “Suppose Dr. Pierce’s Favorite Prescription does not contain any opium, digitalis, opium, or alcohol. First, this does not mean that it never contained any. It is more than probable that when the original report, from which Mr. Bok quoted, was printed, the preparation did contain those ingredients. That is just the curse of the secret nostrum business, that the manufacturers can change the composition at their will and pleasure.”

By 1912, in a promotional “Lady’s Notebook and Calendar” in the Museum’s ephemera collection, “Dr. Pierce’s Favorite Prescription” is offered as a benign cure-all for “weak, over-worked women” that contains “neither alcohol (which to most women is rank poison) nor injurious or habit-forming drugs.”

Thanks to heavy advertising and plenty of freebies like notebooks, Pierce became a well-known figure. In addition to the medicine sales, he was an author, hotel owner, and was elected to the U.S. Congress in 1879.

By the 1920s, advertisements for the “Golden Medical Discovery” were toned down, while still stressing that it was made from native roots and alcohol free. It was touted as a tonic, not a “cure-all”, and was advertised through the late 1950’s.

A Hustler and a Crusader

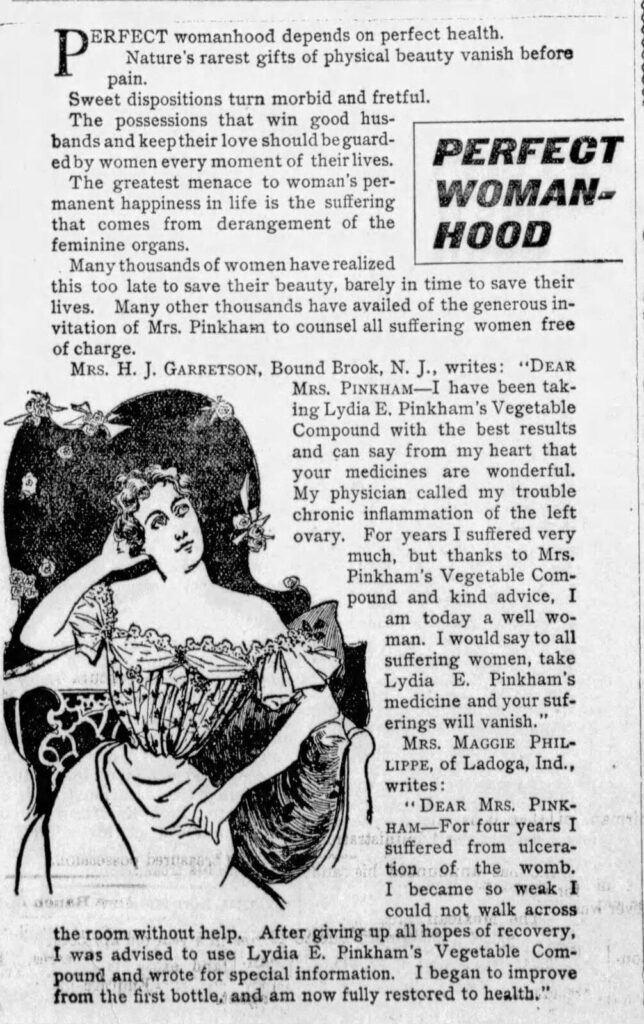

Lydia E. Pinkham is one of the most celebrated and controversial patent medicine producers. Pinkham was dismissed as a quack by the male-dominated medical profession of her time. But her attention to women’s issues, specifically menstrual and menopausal problems, resonated with women who became loyal consumers of “Lydia E. Pinkham’s Vegetable Compound” despite little evidence the herbal/alcohol mix could deliver on her most outlandish claims.

An 1882 Ventura Signal ad promised the medicine would “cure entirely the worst form of female complaints, all ovarian troubles…It will dissolve and expel tumors from the uterus in an early stage of development.” The ad went on to promise it would “under all circumstances act in harmony with the laws that govern the female sex.” The bottles, which sold six for $5, offered relief from “faintness, flatulency, destroys all craving for stimulants, and relieves weakness of the stomach. It cures bloating, headache, nervous prostration, general debility, sleeplessness, depression, and indigestion.”

Pinkham, like many women of her time, brewed remedies at home. She shared her remedy for “female complaints” with her neighbors before offering the “vegetable compound” for sale. Many women preferred to trust recipes shared by other women, even unlicensed practitioners like Pinkham, over male doctors who often diminished women’s concerns as “weakness and hysteria.”

Pinkham built one of the most popular women’s brands of her time through extensive testimonial advertising. Newspaper ads urged women to write to Pinkham. The ads with Pinkham’s “personal responses” continued for years after her death in 1883. It wasn’t revealed that the replies were staff-written until the Ladies Home Journal published a picture of Pinkham’s tombstone in 1905. In 1900 alone, the testimonial ads ran several times a month in the Ventura Free Press, typically with a notation like “Letter to Mrs. Pinkham No. 64,587.” Pinkham’s company also produced books. Nature’s Gift to Women and the Wartime Cook and Health Book are both in the Research Library at the Museum of Ventura County.

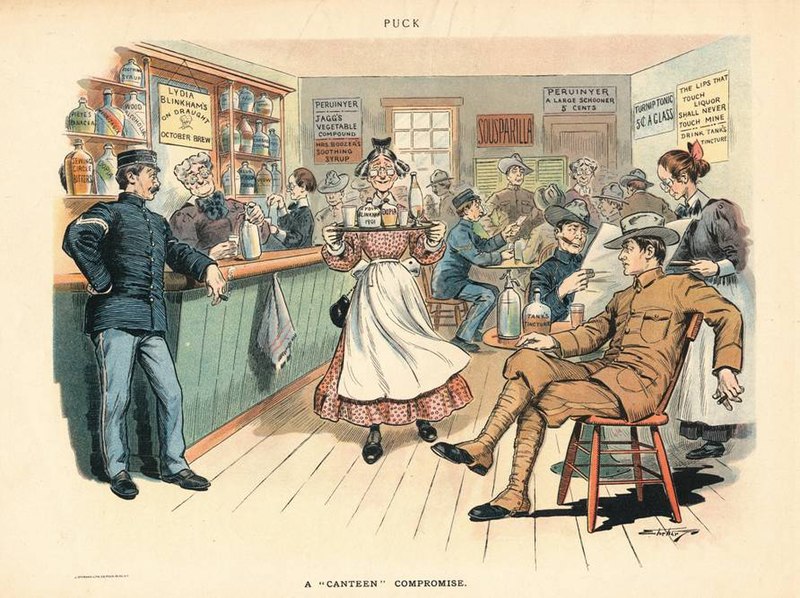

The five herbs used in Pinkham’s original formula were not harmful and had some anti-spasmodic and anti-inflammatory effects. However, 21st century medical trials determined that herbal regimens are not significantly better in relieving menopausal symptoms than placebos. The most effective ingredient in “Lydia E. Pinkham’s Vegetable Compound” was alcohol. The compound was 40-proof or 20 percent alcohol. The potent medicine inspired a World War I song, called “Lilly the Pink” and a 1906 cartoon in the humor magazine Puck that depicted “Lydia Blinkham” (a caricature of Pinkham) serving her medicine to soldiers as a substitute for alcoholic drinks.

In 1922, male medical experts described “Lydia E. Pinkham’s Vegetable Compound” as a “valueless preparation kept on the market for about fifty years by means of lying advertisements and worthless testimonials.” Over a hundred years later, Pinkham is seen both as a shrewd businesswoman, not hesitant to exaggerate, and a crusader for women’s health issues in a day when women were poorly served by the medical establishment.

Rosy Cheeks for Wholesome-Looking Women

“Dr. Williams Pink Pills for Pale People” were advertised in the Ventura Free Press in 1896 as a tonic for the blood and nerves to treat anemia, lack of energy, depression, and poor appetite.

Canadian businessman and politician George T. Fulford bought the patent for the pills in 1890 and turned them into an international brand with testimonial advertising. One Ventura Free Press ad described two men walking down the street. One “has a vigorous, firm, elastic step, his head well up, his eyes bright,” while the other had the appearance of a man who was “broken in health” and had to “whip himself to every task.” The first man had healthy nerves, stimulated by feeding them with the pink pills.

Another ad spoke to women. It noted men seek “wholesome-looking women” with rosy cheeks and good health as their future wives. The ad copy warned, if unaided, a woman’s “regular monthly uterine action” could result in a “pale and sallow complexion and a feeling of exhaustion.” It added that continued use of the pills would “fortify the system against the ravages of the symptoms attending the change [menopause].”

The pills made Fulford a wealthy and influential man. He served in the Canadian Senate. He died at age 53 in 1905, the first Canadian known to have died in an auto accident. The pink pills remained on the market until the 1970s. A modern analysis revealed that the pills contained iron oxide and Epsom salts. Unlike other patent medicines, the pills, with iron as a principal ingredient, were effective in treating anemia.

A Cure for Worms and “Noises in the Head”

Thomas Holloway became a rich man due to the success of “Holloway’s Pills,” a heavily advertised product that promised to cure a surprising range of diseases and ailments. An 1877 ad in the Ventura Free Press urged readers to “mark these facts – the testimony of the whole world.” Testimonials followed with stories of the pills curing headaches, morning sickness, and even “noises in the head.” It promised “Holloway’s Pills” would “invariably cure” kidney disease, asthma, consumption, dysentery, fever, gout, jaundice, kidney and liver complaints, rheumatism, tumors, ulcers, and worms. It is unlikely the pills cured any of these ailments as an analysis showed they contained only aloe, myrrh, and saffron.

Laxative’s Prize Money Giveaway

“Keep the head cool, the feet warm, and the bowels open” was the sage advice offered by makers of the laxative “Smith’s Bile Beans” in an 1894 ad in the Ventura Weekly Post and Democrat. Take two of the tiny pills in the evening and “all day your mind will be clear and cool.” The company encouraged buyers to send their name and address along with the outside wrapper from the bottle to the company. Every day they promised to give away $5 for the first wrapper received in the morning mail and $1 for the next five entries, for a daily total of $10. (The $5 prize would be worth $170 today.) “Smith’s Bile Beans” contained an herb, cascara, that was used for centuries to treat constipation along with rhubarb, licorice, and menthol.

Promised to Grow Hair on Balding Heads

For years, men and women have looked for solutions to prevent hair loss. In the late 1800s, Ventura County residents were inundated with ads for largely ineffective tonics such as the “Skookum Root Hair Grower.” In 1891, a Portland, Oregon man, William C. Halleck registered the name “Skookum Root Hair Grower” as a trademark for a “hair vigor or grower.” An 1894 ad in the Ventura Weekly Post and Democrat, featured a woman with long, flowing locks and described Skookum as a delightful “cooling and refreshing” tonic. Mineral and oil free, it was said to stimulate the follicles, stop hair falling out, cure dandruff, and grow hair on bald heads. Skookum root or hellebore was used by indigenous people in Northwest British Columbia for ceremonial purposes and was seen as an important medicinal plant for the treatment of various skin ailments. It was also respected as one of the most violently poisonous plants on the Northwest Coast. The first clinically proven hair loss medication would not come until 1978 when Minoxidil, sold as Rogaine, was approved by the Food and Drug Administration. Twenty years later, Finasteride, or Propecia, became the second prescribed pill for hair loss, though it is approved for use only by men.

Public Demands Protection from False Advertising

As the 20th century dawned, pressure mounted on patent medicine sellers to end their free-wheeling ways. Doctors and medical associations argued the patent medicines, while not curing illnesses, caused alcohol and drug dependency, and discouraged sick people from seeking proper treatment.

Members of the temperance movement, whose efforts would culminate in the 1920s with Prohibition, also protested the liberal use of alcohol in the medicines. Americans now favored laws to force manufacturers to disclose the ingredients in the remedies and to use more realistic language in their advertising. Action was threatened by several state legislatures.

This was fiercely opposed by the manufacturers. Under the leadership of Frank J. Cheney, whose company sold “Dr. Hall’s Catarrh Cure,” they formed a trade group in 1881 called The Proprietary Association of America. The group’s purpose was to protect the interests of the patent medicine industry against state legislation and regulation. Cheney used a particularly effective tactic known as the “Red Clause” which was printed in red ink and inserted in all newspaper advertising contacts. It said:

It is mutually agreed that this contract is void if any law is enacted by your state restricting or prohibiting the manufacture or sale of proprietary medicines.

The newspapers had grown dependent on the money received from the patent medicine advertising.

Cheney developed a clever advertising scheme that he used for two decades in the Ventura Weekly Post and Democrat as well as newspapers nationwide. He offered a “one-hundred-dollar reward for any case of catarrh that can’t be cured with Hall’s Catarrh Cure.” In 1906 the American Medical Association documented the case of an Arkansas man who requested the reward after consuming 26 bottles without benefit – in fact his case worsened. The company rejected the claim and wrote back to the man saying in many cases, it would require “much more than you have taken for a cure.”

Other catarrh remedies offered similar guarantees. An ad in the Ventura Free Press in 1885 promised a $500 reward for a case of catarrh that “Dr. Sage’s Catarrh Remedy” cannot cure. Catarrh, or post-nasal drip, is a cold symptom that is relatively easy to treat at home with nasal rinses and warm water.

In 1905 and 1906 Collier’s magazine ran a series of influential articles by Samuel Hopkins Adams entitled “The Great American Fraud,” which exposed Cheney’s scheming and many of the deceitful and unsafe methods practiced by patent medicine manufacturers.

The Pure Food and Drug Act was signed into law by President Theodore Roosevelt on June 30, 1906. It prohibited the adulteration or misbranding of foods and drugs, as well as false or misleading advertising. The law required manufacturers to label their products with the exact percentage of any “habit forming drugs” in the ingredients including alcohol, morphine, opium, cocaine, heroin, and cannabis.

Ventura County residents did not read much about the new law even after it went into effect on January 1, 1907. The newspapers referred to it as the “new national food law” or the “pure food law.” They reported that the law provided for the purity and proper handling of foods, drugs and confections and prohibited the short weighting of packaged goods.

The Ventura Free Press was not impressed. The newspaper said the bill was crippled during congressional negotiation and noted that “short-measure canned goods, for instance, can still be sold in the future the same as in the past.”

The county newspapers were silent on the impact of the law on popular patent medicines. The Los Angeles Herald said provisions of the new law were effectively “a death blow to all harmful patent medicines.” The law required that medicines sold in drug stores conform with the United States Pharmacopeia, an official publication containing formulas of medicinal drugs along with their effects and directions for their use. If a medicine differed from the recognized standard in the pharmacopeia, it would be considered “adulterated” under federal law and its label had to specify the differences.

To crack down on cheap cough drops made with alcohol and narcotics, the law prohibited the use of “mineral substances, clays, paraffin, deleterious coloring matter and flavors as well as narcotics or alcoholic products in confectionary.” That prompted Oxnard candy seller Bartlett & Hougham to defend the integrity of its “Bon Bons” with an ad in the Oxnard Courier proclaiming, “The Pure Food Law was never needed for us to make pure confections.”

Ventura County fruit and nut growers were relieved to learn that the new law would not prohibit the sulfuring of dried fruits. The Department of Agriculture held that treating the fruit with sulfur fumes or dipping them in lye “would be considered healthful.” Sulfites are used as a preservative on nearly all commercially dried fruits such as apricots due to their antimicrobial properties.

Manufacturers and stores began to label products with a “guaranty” that their medicine complied with the new drug law. A 1907 ad in the Oxnard Courier for ABC Bohemian Beer notes the product is “guaranteed under the Food and Drugs Act” and “promotes health and good cheer, stimulates the heart and brain, means good fellowship without excess, and no headache in the morning.”

It became clear the 1906 law had major shortcomings. It offered no way to remove inherently dangerous drugs from the market and set such a high burden of proof that the government was rarely able to act against a company for making fraudulent claims.

To help make the public aware of the law’s limitations, the FDA created a traveling exhibit in 1933 to highlight about 100 dangerous, deceptive, or worthless products that the agency lacked the authority to remove from the market.

The shocking exhibition was dubbed the “American Chamber of Horrors” and was used to generate public support for a new federal food and drug law: the 1938 Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act. All new drugs had to be proven safe for their labeled use before they could be marketed. Manufacturers were required to provide a complete listing of all ingredients and adequate directions for the product’s use. Amendments to the laws in 1951 established clear distinctions between prescription and over-the-counter drugs. Tests of a drug’s effectiveness were not required until 1962. A “Drug Facts” label has been required on all over-the-counter medicines since 2002.

A Few Patent Medicines Live On

While it was not the norm, some of the patent medicines delivered on their promises and are still sold including Listerine, Bayer Aspirin, Milk of Magnesia, and Richardson’s Croup and Pneumonia Cure Salve, though it is known today as Vick’s VapoRub. Other survivors include Anacin, the laxative Carter’s Little Pills, Doan’s Pills, Geritol, and Fletcher’s Castoria, which has been renamed Fletcher’s Laxative for Kids.

Self-medication with the enormous array of over-the-counter products continues to be a popular form of treatment for many Americans.

Make History!

Support The Museum of Ventura County!

Membership

Join the Museum and you, your family, and guests will enjoy all the special benefits that make being a member of the Museum of Ventura County so worthwhile.

Support

Your donation will help support our online initiatives, keep exhibitions open and evolving, protect collections, and support education programs.

Bibliography

- “Early Pain Theories and Remedies.” ATrain Education. Accessed November 2, 2023. https://www.atrainceu.com/content/1-early-pain-theories-and-remedies-0.

- “80 Years of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act.” U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Last modified July 11, 2018. https://www.fda.gov/about-fda/fda-history-exhibits/80-years-federal-food-drug-and-cosmetic-act.

- “9 Creepy Things That Used To Happen In Doctors’ Offices.” Bustle. Last modified February 16, 2018. https://www.bustle.com/p/9-creepy-things-that-used-to-happen-in-doctors-offices-8098688.

- American Medical Association. Nostrums and Quackery: Articles on the Nostrum Evil and Quackery Reprinted from the Journal of the American Medical Association. 1912.

- Ashcraft, Jenny. “Lotions and Potions in the Papers.” – The Official Blog of Newspapers.com. Last modified July 21, 2023. https://blog.newspapers.com/lotions-and-potions-in-the-papers/?xid=5571&utm_source=Internal&utm_medium=Email&utm_campaign=Find_July-2023.

- Ayer’s American almanac, for the use of farmers, planters, mechanics, mariners, and all families. Lowell, Mass: Dr. J.C. Ayer & Co, 1865.

- Babitz, Arthur. “Ayer’s Cherry Pectoral.” The History Museum of Hood River County. Last modified March 18, 2023. https://www.hoodriverhistorymuseum.org/ayers-cherry-pectoral/.

- “Balm of America: Patent Medicine Collection.” National Museum of American History. Accessed November 2, 2023. https://americanhistory.si.edu/collections/object-groups/balm-of-america-patent-medicine-collection?ogmt_page=balm-of-america-history.

- “Balm of America.” Smithsonian Institution. Accessed November 2, 2023. https://www.si.edu/spotlight/balm-of-america-patent-medicine-collection/history.

- “Changes in Medicine During the 19th Century.” American Battlefield Trust. Last modified October 5, 2023. https://www.battlefields.org/learn/articles/changes-medicine-during-19th-century.

- “Chapter 5: Hair Loss Treatment History.” Peter Panagotacos, MD: Board Certified Dermatologist Cow Hollow San Francisco, CA: Hair Doc. Accessed November 2, 2023. https://www.hairdoc.com/contents/chapter-5-hair-loss-treatment-history.

- “Dr Pierce’s Nasal Douche.” The Quack Doctor – Stories from Medicine’s Past. Last modified October 9, 2018. https://thequackdoctor.com/index.php/dr-pierces-nasal-douche/.

- “Dr Pierce’s Favorite Prescription, Buffalo, New York.” Old Main Artifacts. Last modified July 23, 2018. https://oldmainartifacts.wordpress.com/2018/06/28/dr-pierces-favorite-prescription-buffalo-new-york/.

- “Dr. Pierce’s Pleasant Pellets.” National Museum of American History. Accessed November 2, 2023. https://americanhistory.si.edu/collections/search/object/nmah_1338049.

- “Dr. Pierce’s Pleasant Pellets.” The Quack Doctor – Stories from Medicine’s Past. Last modified October 9, 2018. https://thequackdoctor.com/index.php/dr-pierces-pleasant-pellets/.

- “Dr. Pierce’s Golden Medical Discovery.” Bay Bottles. n.d. https://baybottles.com/tag/dr-sages-catarrh-remedy/.

- “Dr. Thomas’ Eclectric Oil.” Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia. Last modified September 21, 2023. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dr._Thomas%27_Eclectric_Oil.

- “Fletcher’s Laxative.” Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia. Last modified June 10, 2023. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fletcher%27s_Laxative.

- “For Bald Heads! (My Ears Are Burning).” Chinook Jargon. Last modified December 28, 2017. https://chinookjargon.com/2017/12/28/for-bald-heads-my-ears-are-burning/.

- “Good For Everyone Herbal Tonic.” Edgar Cayce’s Association for Research and Enlightenment | Edgar Cayce’s A.R.E. | Edgar Cayce’s A.R.E. Accessed November 2, 2023. https://www.edgarcayce.org/about-us/blog/blog-posts/good-for-everyone-herbal-tonic/.

- “Hair Raising Stories.” Accessed November 2, 2023. https://www.hairraisingstories.com/Products/AYER_HV.html.

- “History of Patent Medicine.” Hagley. Last modified June 21, 2017. https://www.hagley.org/research/digital-exhibits/history-patent-medicine.

- “Home Remedies and Quack Cures: Hall’s Catarrh Cure.” Digging History. Last modified April 2, 2020. https://digging-history.com/2013/11/16/home-remedies-and-quack-cures-halls-catarrh-cure/.

- “Just a Moment…” Just a Moment… Accessed November 2, 2023. https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/medicine-and-dentistry/stramonium.

- Kam, Katherine. “Antique Medicines.” WebMD. Last modified May 7, 2006. https://www.webmd.com/a-to-z-guides/features/look-back-old-time-medicines.

- Landrigan, Leslie. “James Cook Ayer, Sarsaparilla King of Lowell, Mass.” New England Historical Society. Last modified May 4, 2022. https://newenglandhistoricalsociety.com/james-cook-ayer-sarsaparilla-king-lowell-mass/.

- “Large Outbreak of Jimsonweed (Datura Stramonium) Poisoning Due to Consumption of Contaminated Humanitarian Relief Food: Uganda, March–April 2019 – BMC Public Health.” BioMed Central. Last modified March 30, 2022. https://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12889-022-12854-1.

- “Let’s Comb Through The History Of Hair Loss.” Fortitude Functional Nutrition. Last modified January 12, 2023. https://fortitudefunctionalnutrition.com/blog/lets-comb-through-the-history-of-hair-loss.

- “List of Patent Medicines.” Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia. Last modified September 10, 2023. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_patent_medicines.

- Los Angeles Herald. “Pure Food Law in Effect Jan. 1.” July 29, 1906, 41.

- “Lydia Pinkham.” Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia. Last modified October 27, 2023. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lydia_Pinkham.

- “Medicine in 1860s – Holloway’s Pills.” Web Hosting – Faculty and Staff – University of Victoria. Accessed November 2, 2023. https://web.uvic.ca/vv/student/medicine/holloway.htm.

- Moorpark Enterprise. “Dry Haul in Raid on Oxnard Drug Co.” March 6, 1924, 1.

- Morning Free Press (Ventura). “Sulfuring of Dried Fruits.” January 30, 1907, 1.

- “Mrs. Winslow’s Soothing Syrup.” Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia. Last modified April 3, 2023. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mrs._Winslow%27s_Soothing_Syrup.

- Oxnard Courier. “Ad – Begin the New Year Right.” January 25, 1907, 8.

- “Patent Medicines to Cure Any Ailment.” California Secretary of State. Accessed November 2, 2023. https://www.sos.ca.gov/archives/trademarks/patent-meds.

- “R. V. Pierce, M. D., Buffalo, N. Y., Dr. Pierce’s Golden Medical Discovery.” Bay Bottles. Last modified July 27, 2023. https://baybottles.com/2022/01/28/r-v-pierce-m-d-buffalo-n-y-dr-pierces-golden-medical-discovery/.

- Ridge, Gerald K. “Brief History of Ventura County Medicine.” Journal Western Medicine, September 1965.

- Sheridan, E. M. “Good Old Days When Children Were Plenty.” Ventura Weekly Post and Democrat, November 7, 1923.

- Sheridan, E. M. “Late Dr. Bard Tells of Pioneer Doctoring.” Ventura County Star, January 13, 1930.

- “Simmon’s Liver Regulator.” Accessed November 2, 2023. https://maryfransmuse.weebly.com/simmons-liver-regulator.html.

- “Skookum Root: Ethnobotany of Hellebore (Veratrum Viride) in Northwest British Columbia | Ethnobiology Letters.” Ethnobiology Letters. Accessed November 2, 2023. https://ojs.ethnobiology.org/index.php/ebl/article/view/1298/639.

- “Snake Oil Was Cheap, Widely Available and Had Some Curative Benefits. But What Was Actually in It?” ABC (Australian Broadcasting Corporation). Last modified October 16, 2021. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2021-10-17/snake-oil-traditional-medicine-history-bad-reputation/100485044.

- “The Story of George Taylor Fulford I and His Pink Pills for Pale People.” Museum of Health Care Blog. Last modified October 14, 2021. https://museumofhealthcare.blog/the-story-of-george-taylor-fulford-i-and-his-pink-pills-for-pale-people/.

- “Substance Abuse and Addiction.” WebMD. Accessed November 2, 2023. https://www.webmd.com/mental-health/addiction/default.htm.

- Trickey, Erick. “Inside the Story of America’s 19th-Century Opiate Addiction.” Smithsonian Magazine. Last modified January 4, 2018. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/inside-story-americas-19th-century-opiate-addiction-180967673/.

- Ventura Free Press. “Ad – A Nerve Food Found.” October 2, 1896, 7.

- Ventura Free Press. “Ad – A Short Talk on Medicine.” July 24, 1896, 3.

- Ventura Free Press. “Ad – Best Cough Medicine for Children.” April 8, 1904, 8.

- Ventura Free Press. “Ad – Chamberlain’s Pain Balm.” December 28, 1894, 6.

- Ventura Free Press. “Ad – Delmont’s Drug Store.” April 17, 1880, 3.

- Ventura Free Press. “Ad – How to be Rid of Calomel.” October 1, 1886, 4.

- Ventura Free Press. “Ad – The End of the World in 1914.” November 16, 1900, 6.

- Ventura Free Press. “Editorial.” July 10, 1896, 4.

- Ventura Free Press. “Local Brevities.” August 7, 1891, 5.

- Ventura Free Press. “Pure Food Bill.” July 6, 1906, 4.

- Ventura Free Press. “Somis Scraps.” November 10, 1893, 2.

- Ventura Free Press. “The Game Laws.” September 24, 1881, 1.

- Ventura Free Press. “The Home Cookbook.” April 23, 1886, 4.

- Ventura Signal. “Ad – Lydia Pinkham.” September 23, 1882, 3.

- Ventura Signal. “Ad-Dr. Pierce Golden Medical Discovery.” December 11, 1875, 5.

- Ventura Weekly Post and Democrat. “A Medical Firm Gives Away Cash.” December 8, 1893, 1.

- Ventura Weekly Post and Democrat. “Ad – $5,000 Reward.” April 12, 1907, 4.

- Ventura Weekly Post and Democrat. “Ad – A Sure Cure for the Liquor or Opium Habits.” August 7, 1891, 3.

- Ventura Weekly Post and Democrat. “Ad – Ayer’s Sarsaparilla.” October 19, 1906, 2.

- Ventura Weekly Post and Democrat. “Ad – Dr. Pierce’s Favorite Prescription.” October 27, 1899, 3.

- Ventura Weekly Post and Democrat. “Ad – Dr. Pierce’s Pleasant Purgative Pellets.” February 12, 1876, 9.

- Ventura Weekly Post and Democrat. “Ad – The Fact.” August 4, 1893, 4.

- Ventura Weekly Post and Democrat. “Ad-Eclectric Oil.” June 15, 1906, 5.

- Ventura Weekly Post and Democrat. “Cocaine.” December 24, 1885, 2.

- Ventura Weekly Post and Democrat . “Local Brevities.” September 30, 1886, 3.

- Ventura Weekly Post and Democrat. “Local Brevities.” February 2, 1894, 3.

- “What It Was Like To Be Sick In 1884.” AMERICAN HERITAGE. Accessed November 2, 2023. https://www.americanheritage.com/what-it-was-be-sick-1884.

- Wills, Matthew. “The Bitter Truth About Bitters.” JSTOR Daily. Last modified July 1, 2021.