By Library Volunteer Andy Ludlum

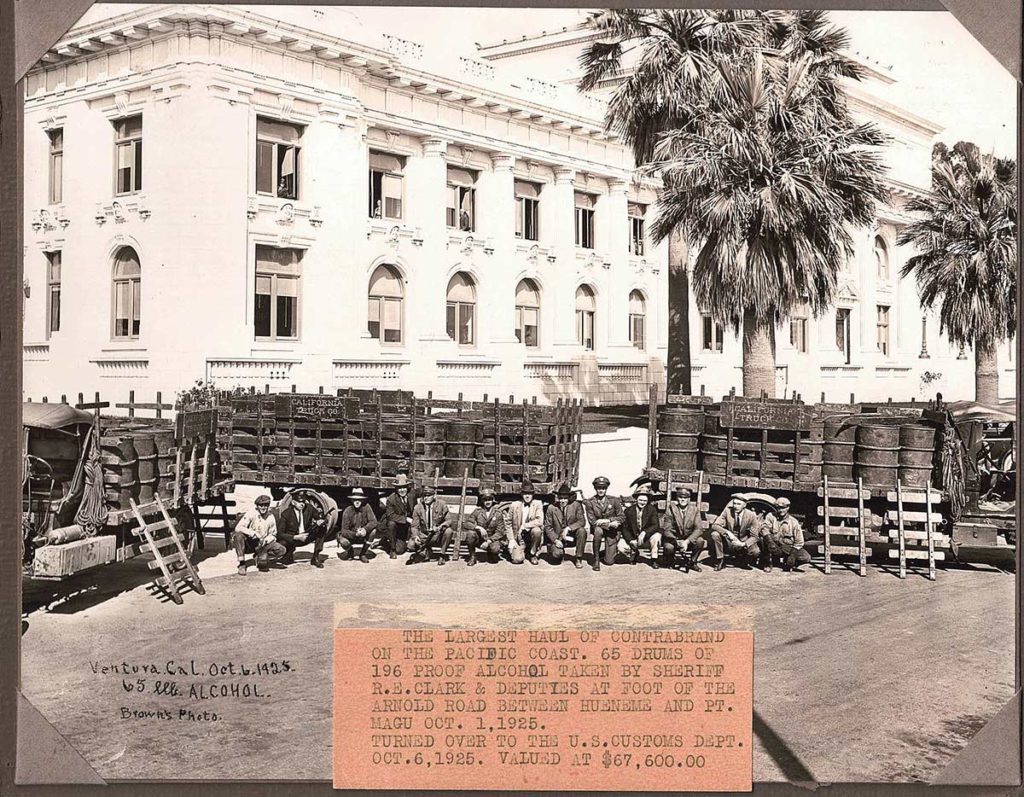

It was the opening day of duck season in October 1925. The last thing the hunters expected to bag along the shore east of Hueneme was dozens of 50-gallon barrels of pure alcohol.

Ventura County and the rest of the nation had been legally dry for nearly five years after voters approved Prohibition with the passage of the 18th amendment. Smugglers towing a raft loaded with the barrels were apparently spooked by the hunters’ gunfire and abandoned their cargo. One hundred thirty barrels drifted in with the tide near Arnold Road. Despite the hunters “keeping watch,” locals scooped up some of the barrels and loaded them in their cars. When Ventura County Sheriff Robert Clark and his deputies arrived on scene, they found tracks in the sand where barrels had been rolled into the waiting vehicles. Sheriff Clark’s son William recalled that three normally reliable people fooled the sheriff into giving them some of the barrels to take to the “poor sisters at St. John’s Hospital who didn’t have any alcohol to rub their patients with.” The sheriff only learned he had been conned when the administrator from St. John’s came to him with the same request. Clark only managed to recover half the barrels that washed ashore that day. Nonetheless, it was celebrated as a great law enforcement victory as he posed with his men in front of the Ventura County Courthouse. It was the largest haul of contraband on the Pacific Coast, 65 barrels estimated to be worth almost $68,000 – more than $1 million today.

This story illustrates one of the key problems with America’s 13-year experiment with Prohibition. While outwardly supportive, at least half the population wanted to carry on drinking and saw the laws as applying to others.

Ventura Considered Temperance for Decades

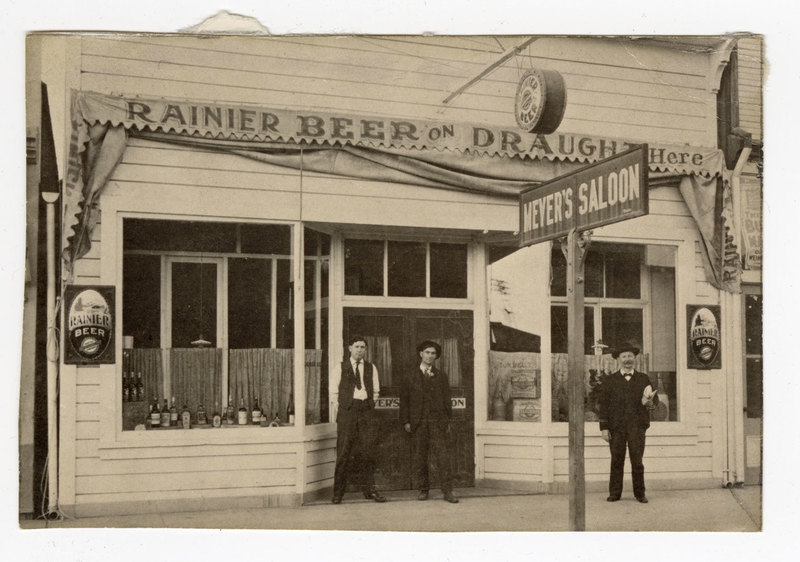

Ventura had a history with temperance long before the passage of Prohibition. In 1881, Ventura was a town of just 1,300 people yet it had 17 saloons. By the turn of the century, Ventura still had 14 saloons and Oxnard had 12. The Anti-Saloon League and Woman’s Christian Temperance Union were the leading proponents of temperance in the county. They targeted saloons because of the toll alcoholism had on families. The groups were behind almost yearly attempts to convince voters to outlaw saloons. In 1903, Ventura County passed an anti-saloon ordinance, though it only applied to the unincorporated areas. In 1906, Santa Paula voted to go dry. Oxnard residents voted overwhelmingly in favor of saloons in 1912. In 1913, after many failed attempts, the city of Ventura voted to go dry by a 168-vote margin out of 1388 votes.

By the time national Prohibition went into effect, over half the population of the United States lived in dry areas. Congress passed the Volstead Act, the enabling legislation for the 18th Amendment which established Prohibition. Congressman Andrew J. Volstead, the sponsor of the law, drank alcohol. President Woodrow Wilson vetoed the Volstead Act, citing both moral and constitutional objections. But Congress overrode his veto the same day. Ratification of the amendment began on January 7, 1919. California ratified the amendment on January 13th and by the 16th it was all over when Nebraska became the 36th state to ratify the 18th Amendment. The law banned the manufacture, sale, and transportation of alcoholic beverages. Prohibition would go into effect one year later on January 16, 1920.

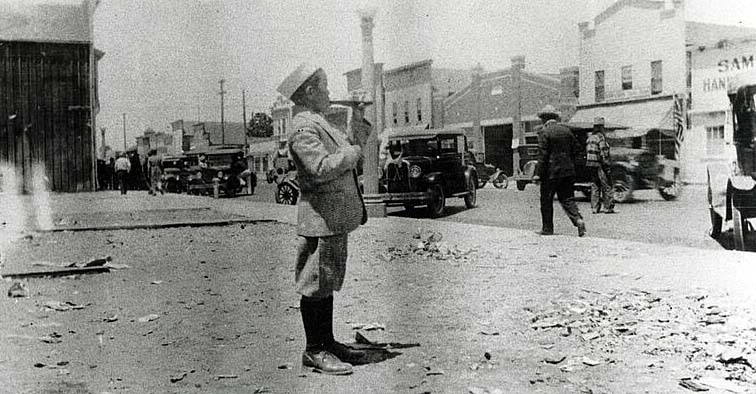

The Prohibition years in Ventura County were tame compared to the popular images of the Roaring 20’s in New York or Chicago, with gangsters, glitzy speakeasies, and widespread corruption. Ventura County in 1920 was isolated and sparsely populated with about 28,000 residents.

Only Oxnard, Ventura, and Santa Paula were large enough to meet the federal definition of an “urban” area. It was the county’s remoteness that made it an ideal place to operate illegal stills. Miles of secluded coves and beaches offered places for rumrunners to land illegal liquor from ships offshore and rush it to Los Angeles.

The Dread 16th of January

The Oxnard Daily Courier referred to the start of Prohibition as the “dread 16th of January. The day is being hailed with the profoundest grief by some and with the greatest joy by others, both of them extremists. The average citizen, on the contrary, has felt it was coming for some time, and feels resigned that it might just as well be now as later.” The Prohibition law’s critical flaw was that it did not prohibit the purchase or consumption of alcohol. People were free to drink in their own home or in the home of a friend. They could keep a stock of liquor in their homes, and they could buy liquor with a medical prescription from a doctor. They couldn’t carry a pocket flask, take liquor to a hotel or restaurant, and drink it in public dining rooms, or give or receive a bottle of liquor as a gift. It was also illegal to buy or sell formulas for home-made liquor or to make anything with an alcohol content above one-half of one percent in the home.

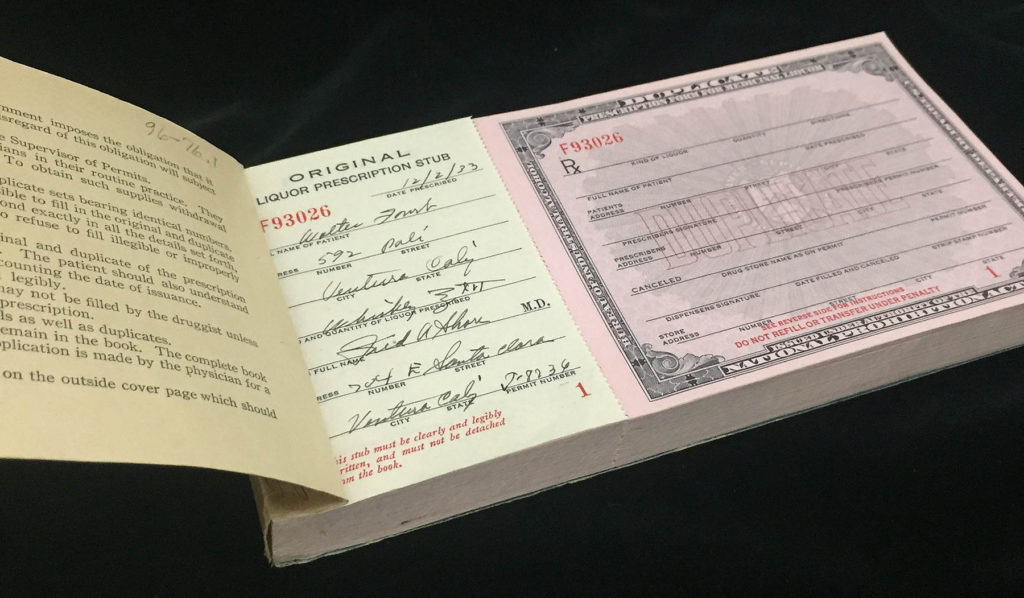

Writing alcohol prescriptions was highly profitable for doctors. Some doubled their annual income. Each doctor was allowed to write 400 “exemption” prescriptions per year. Alcohol was prescribed for dozens of conditions including diabetes, cancer, asthma, snake bite, lactation problems and old age.

On the day before Prohibition went into effect, the last barrels of California wine were put on a ship bound for Asia. The cargo was valued at $1.5 million, more than $20 million today. But Prohibition didn’t dampen the public demand for grapes. Dried grapes were sold in bricks or blocks. They carried a disingenuous warning. “After dissolving the brick in a gallon of water, do not place the liquid in a jug away in the cupboard for twenty days, because then it would turn into wine.”

Some Oxnard saloons stayed open to sell cigars and soft drinks. Henry Meyer leased his property to two men who began selling soft drinks and sandwiches. Former saloon owners asked Oxnard trustees to refund the money they had paid the city for their liquor licenses. In April City Attorney Charles Blackstock advised the trustees that refunding the money would exceed their authority. He added that the fact the owners “are no longer licensed to sell liquor in the city of Oxnard, is not due to any action taken by you.”

The struggle for national temperance quickly became mired in hypocrisy. One of California’s two Prohibition enforcement directors admitted serving liquor to his guests because he was “not a prude.” The nation’s highest law enforcement officer, U.S. Attorney General Harry Daughtery, was implicated in alcohol corruption. The Speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives operated an illegal still. In December 1920 it was revealed by staff cleaning congressional offices in the nation’s capital that many outspoken dry congressmen had hidden private stocks of whiskey in their offices. One senator, known for his spellbinding dry oratory, had stored five barrels of Kentucky bourbon to get through the “terrible drought.”

Prohibition Was Not Equitably Enforced

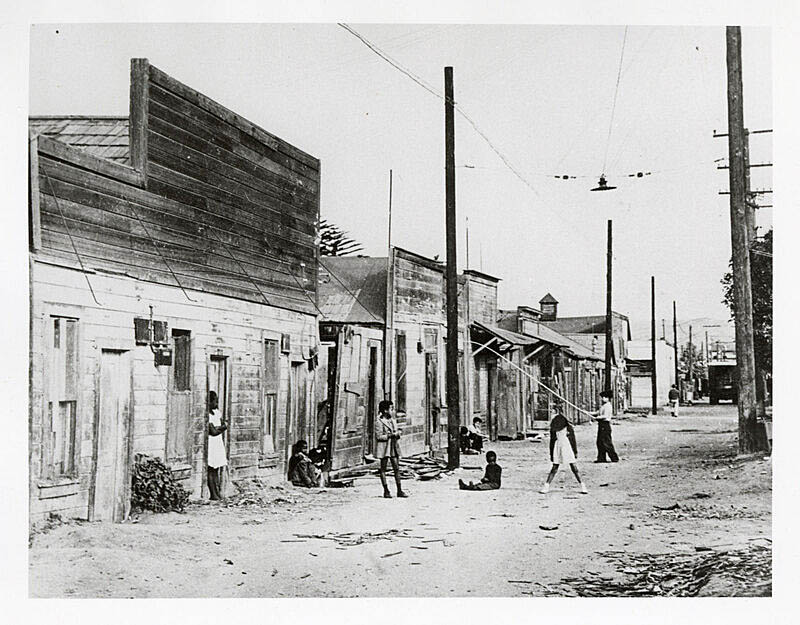

In March 1920 Ventura County Sheriff E. G. McMartin staged a raid targeting Oxnard’s China Alley. The neighborhood of mostly Chinese immigrants became a frequent law enforcement target over the next decade. The Chinese had encountered hatred and racism since coming to Oxnard in the late 1800s to work in the sugar beet factory. China Alley ran through the middle of their largely segregated neighborhood located on Saviers Road (now Oxnard Boulevard) between Fifth and Sixth Streets. Liquor had been openly sold for months in “blind pigs” operating out of houses of prostitution in China Alley. The term “blind pig” refers to lower-class establishments that sold backroom liquor during prohibition. The name is thought to be a slang term originating with police officers bribed to turn a blind eye to the illegal sales. The difference between a blind pig and speakeasy was that the speakeasy was usually a higher-class establishment with food and entertainment.

Compounding early enforcement problems in Ventura County was the fact that there was no corresponding state law to support federal Prohibition. In fact, it had been rejected by the voters five times between 1914 and 1920. The Volstead Act was designed to work in tandem with state enforcement, but “arrangements” between the feds and local police proved to be ineffective.

The reality of Prohibition brought almost immediate public criticism. The Courier editorialized that if Prohibition remained “on the statute books, it should be obeyed.” The paper blamed the growing public resentment on “liquor interests” and said if it was allowed to grow, “it may eventually undo this great reform, and force the repeal of the prohibition amendment.”

Prohibition Led to Social Changes

Prohibition reversed historic employment and social patterns. The theater was reportedly helped by Prohibition. One of the leading stage producers said a lot of the money that had been wasted on liquor was redirected to shows. “Now that there are no more saloons, thousands who used to find diversion in them naturally turn to theaters instead. And despite the much-deplored low standards of the American stage, it does seem those standards are a little higher since the plays have been subjected to the judgement of an entirely sober audience.” Because the family had more money to go around, children were staying in school instead of leaving when they were old enough to work. The Courier reported women in Boston were quitting their office floor cleaning jobs. They no longer felt pressure to support their families because their husbands were no longer “drinking” their wages.

At the end of 1920, a Courier commentary had a stinging rebuke for the Milwaukee Museum which had accepted two bottles of banned 6% beer into its collection. The newspaper suggested, “Why not, while the materials are still at hand, preserve a whole barroom? To make the picture complete, museums could file away, along with the bottles and things, some moving pictures of people under the influence of strong beverages, and phonographic recordings of their conversation, and perhaps some sets of criminal and sociological statistics showing the ultimate effects of alcohol on society.”

Young Woman Opens Ventura County Speakeasy

Fresh out of prison for trying to buy an iron with a stolen check, 18-year-old Sally Stanford arrived in Santa Paula at the start of Prohibition. She had learned about bootlegging from her fellow inmates. In her book “The Lady of the House,” Stanford described her speakeasy as a “one-woman business” in a “beautiful old Spanish house on a palisade overlooking the Pacific…I used to close at ten o’clock. I wasn’t about to shake up the neighbors and risk squeals to the cops.” Even when the law came calling Stanford avoided arrest “because I had planted all the hooch in the backyard under some rose bushes.” She added sarcastically, “My customers were just a lot of nice guys from the region with barely enough left over from the necessities of life, like booze, to pay for the luxuries, like bread, potatoes and shoes.” Stanford would buy gallons of alcohol in bulk, “Five gallons cost twenty-five dollars. This had to be cut, flavored with bourbon extract, colored with caramel, bottled, and labeled, then aged. I used to age mine about 48 hours.” She finished her liquor in the bathtub. “A lot of jokes have been made about bathtub gin, but there never was a container more convenient for the production of high-class hooch. In an emergency, the plug could be pulled, and the evidence was far out to sea.” She bought her raw materials from a place called The Rincon. ”It was popular with bootleggers because the county line ran right through the middle of the house and was so marked.” When the Santa Barbara County Police arrived, “we all rushed to the Ventura County side of the house and thus couldn’t be pinched. It was vice versa when the Ventura County cops dropped by.” Stanford married a San Francisco attorney in 1923 and moved north. She used her bootlegging money to open one of the city’s famous bordellos

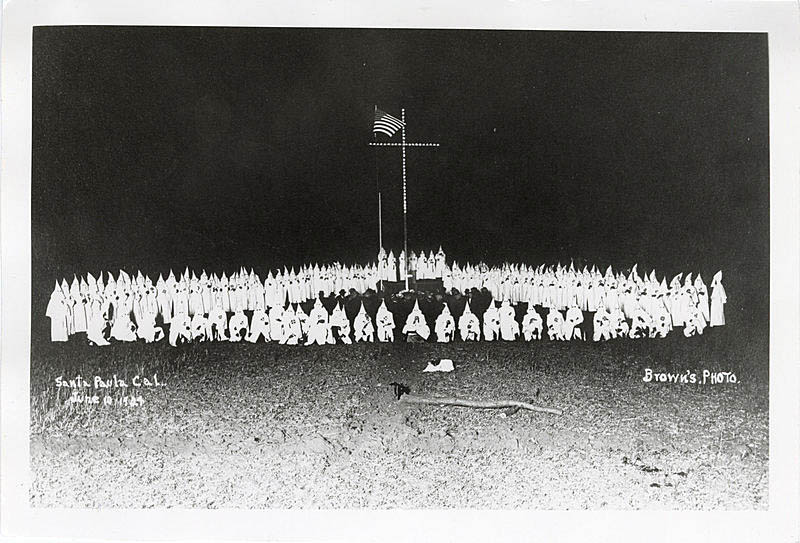

Prohibition and the Ku Klux Klan

Prohibition in part sparked a brief resurgence of Ku Klux Klan activities in Ventura County and throughout the United States in the first half of the 1920s. The Klan made enforcement of Prohibition a centerpiece of its so-called “reform agenda.” In some parts of the country, its vigilante enforcement of liquor laws made it the extreme militant wing of the temperance movement. On August 25, 1921, The Signal newspaper in Santa Clara River Valley endorsed the Ku Klux Klan. The Klan had a regular presence outside Santa Paula. The editorialist said, “The so-called atrocities of the Klan do not seem so cold-blooded or unjustifiable when one digs down underneath for the prime motives of their actions. If the Ku Klux Klan are going to make it their business to cope with booze runners, kidnappers, white slave artists and others who work in the dark, we say hop to it.”

Remote Santa Paula was a favorite spot for bootleggers to fire their stills and avoid the law. In 1921 a Mrs. Orcutt told the sheriff she had been approached by four men wanting to rent her unused garage. At first, she refused, but after the men drove their car into the garage and paid the woman a month’s rent, she relented. It soon got around Santa Paula that a blind pig was operating in town. The local Justice of the Peace went to investigate and questioned the men in Mrs. Orcutt’s garage. When he returned to his office in downtown Santa Paula, he called the Sheriff. By the time the Sheriff arrived, the men had cleared out, leaving behind two large wooden kegs, filled with colored water and a small amount of whiskey to give it an authentic smell. Law enforcement was often satisfied with just driving bootleggers and blind pig operators out of town. The Dew Drop Inn in Camarillo became known as a “blind pig resort,” a place to sample bootleggers’ products. By increasing his presence in Camarillo, Sheriff Bill McGlinchey made it difficult to operate, forcing the proprietor of the Dew Drop to close and move on. Meanwhile Oxnard Police Chief A. J. Murray focused on finding illegal stills and making mostly low-profile arrests.

In 1922, California officially went dry when voters passed Proposition 2, the Prohibition Enforcement Act, or the Wright Act, named for its sponsor, Santa Clara County Assemblyman Theodore M. Wright. Past opposition to a state dry law was muted because, with national Prohibition, the Wright Act was seen as a matter of amplified enforcement through state, county, and municipal police. It did not change existing state laws regulating search, seizure, and arrests by officers. Nor did the act give an officer the legal right to enter a house without a search warrant or the legal right to search before arrest. However, officers were quickly granted the go-ahead, in “emergency cases” when they had reasonable suspicion, to arrest a suspected bootlegger and search him and his automobile without a warrant.

The federal government decided to consolidate the nation’s 42-million-gallon supply of whiskey, brandy, and gin in 14 bonded warehouses, one of which was in Los Angeles. Los Angeles eventually received one million gallons of the supply. Three shifts of guards, armed with Colt automatic pistols and automatic rifles guarded the warehouse around the clock. Internal Revenue Collector Rex B. Goodcell said “ driving a camel through the eye of a needle would be an easy task” compared to what a bootlegger would have to overcome to steal liquor from the warehouse. Meanwhile a nation-wide poll conducted by he Literary Digest found that 38% of respondents favored enforcement of Prohibition. But 41% favored modification, and 21% favored its repeal.

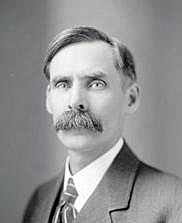

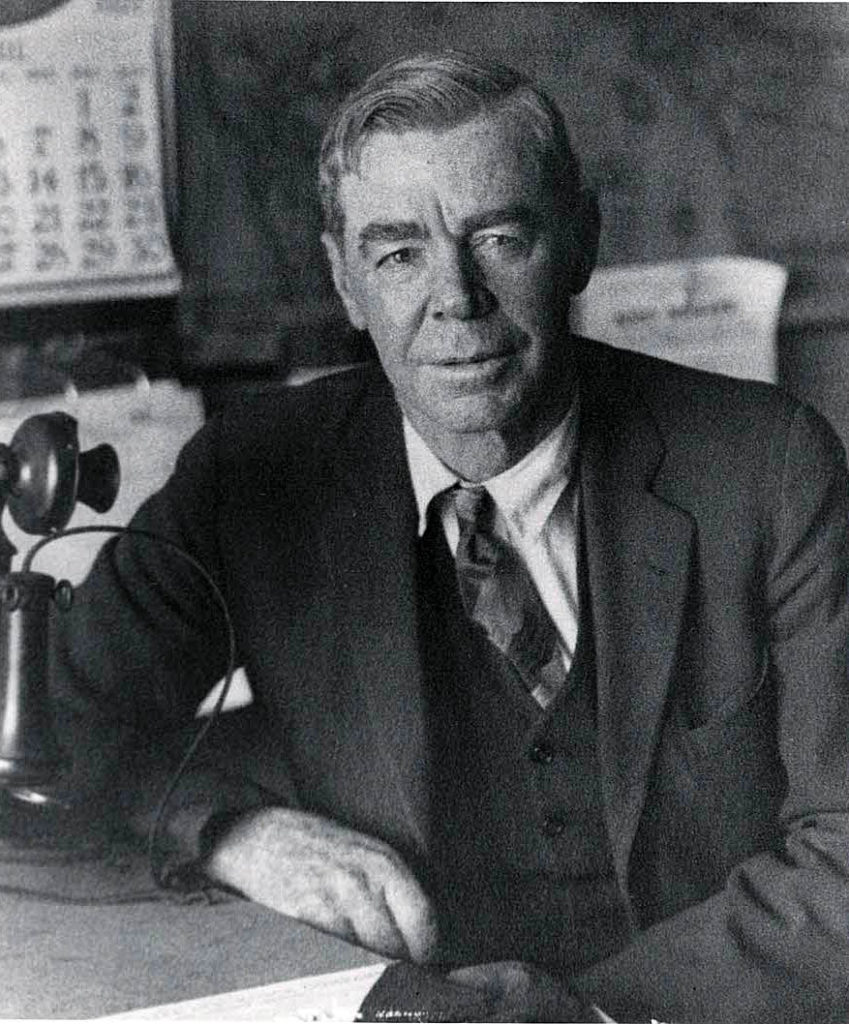

The Lawman in the Black Hat

The year 1922 marked the arrival of perhaps the most influential local law enforcement officer of the Prohibition era. Robert Clark was elected Ventura County Sheriff, replacing tax collector T.W. McGlinchey who was appointed sheriff when E.G. McMartin was killed in the line of duty. Clark was sheriff until 1933 and most of his investigations and arrests involved bootlegging. Clark was known for his signature black cowboy hat, given to him by his terminally ill brother, Hugh. Clark’s son William Pettit Clark in a 1979 oral history interview with the Museum of Ventura County recalled, “Ventura and Santa Barbara Counties were two counties in the state that made a sincere effort to enforce the prohibition law.” In another 1979 oral history, retired Highway Patrolman Robert J. Parr said, “Bob was a great man. You don’t meet many people like him. He gets this grin and gets by with anything.”

One of the most unique smuggling attempts occurred in the summer of 1922. It was reported that a high-powered passenger aircraft had landed in Ventura’s Seaside Park and unloaded liquor. Agents had been following the plane from Los Angeles. Police finally swooped down and arrested the pilot and his passenger at the Santa Barbara Airport, but not before a large touring car, presumably with some of the booze, was seen speeding away. The two men in the plane were turned over to federal authorities.

Oxnard police chief Murray continued to target bootleggers. While he confiscated stills, the bootleggers evaded him. Murray told the Courier it was hard to catch a man in the act of operating a still. He believed the bootleggers were being tipped off to his arrival as sometimes he’d find hot, but unattended stills. Frustrated by just dumping the illegal brew down the sewer, Murray threatened to arrest the property owners if he could not find the still operators. Sheriff Clark raided the Camarillo drugstore operated by Peter Kapp. Gin, wine, and whiskey was confiscated, and his prescriptions were checked for the illegal sale of intoxicating liquors. State authorities charged him with violating the Wright Act and took him to Los Angeles for trial.

In 1923 one rather brazen bootlegger made news when he tried to sell booze to a quiet-living Santa Paula celebrity. Edward C. Converse, known as the “cowboy millionaire,” had come to Santa Paula in 1906 and developed a 6,000-acre cattle ranch. In the summer of 1921, his father, a steel industry tycoon, died leaving Converse and his two brothers a $100 million fortune. Inheriting $33 million had little effect on Converse. He carried on with his life as a gentleman rancher with only a few indulgences, one of which was hiring a butler. The butler was under strict orders never to reveal Converse’s whereabouts to the many opportunists who would come calling. Converse told the Courier he was “at work around his pig pens” when he noticed a large car drive up. He watched a man get out of the speedy, luxury sedan and talk with his butler. He was sent away a few minutes later. The butler told Converse that the man had introduced himself as a “first class bootlegger” who could supply Converse with excellent liquor if he wanted any.

In February 1924 one of the biggest liquor raids in the history of Oxnard was conducted, not by the Police Chief Murray, but by Sheriff Clark. Clark’s son William recalled “Dad decided things had gone far enough. They raided China Alley and they actually fenced off a certain area in China Alley and made…arrests.” Tipped by informants, Clark and his deputies traveled in three cars to stage an unusual morning raid, targeting all the spots along Saviers Road suspected of selling liquor. Dozens of bottles of liquor were seized and by 10:30 in the morning, Clark had arrested 15 bootleggers.

Raid Causes a Police Department Shakeup

By 1924, Oxnard had developed the unenviable reputation as the “most wide-open town on the coast between San Diego and San Francisco.” A citizen’s group insisted there was flagrant violation of “our good and wholesome laws” and that Murray’s police department had turned a blind eye towards gambling, prostitution, and illegal liquor sales in China Alley. The group called on city trustees to fire the chief and his officers. One member, George Harlan said, “This is a dirty town, the police force is responsible because they don’t enforce the laws, therefore throw them out.” In a front-page article, the Ventura Post chimed in, “It is not a fight of Ventura against Oxnard…it is merely a question of the decent people of Oxnard, Ventura and all other towns in the county standing shoulder to shoulder for the enforcement of the laws.” The Post editorial harshly concluded with racially charged rhetoric, “when the thing is accomplished and China Alley is wiped out and all its ashen-faced oriental dope peddlers and its worse white maquereaux [a French word in this context meaning “pimps”] and blind-piggers are sent south of the Mexican border, it will be the people of Oxnard who will have the credit. They have been long suffering, but they are now awake.”

The trustees called a town meeting. They invited the District Attorney, Ventura County Sheriff Clark, and several “prominent Oxnarders.” Not invited was police chief Murray who continued to resist calls for his resignation. He told the Oxnard Daily Courier he wanted the public to know the truth, “I want a square deal. Either prove me guilty of the charges made or prove me innocent, that my name may be either stained forever or shown clean.” At the meeting, the Reverend Tom Burden said the public had lost confidence in the police department, noting it took Sheriff Clark and his deputies to make arrests in China Alley. He summed up the issue, “Will the city council back up rigid enforcement of the law and if the council demands it, will the city police do their duty?” The meeting ended when the trustees pledged to enforce the law and ask for cooperation and “harmony in the future” between city and county police. Mayor H.H. Eastwood said unless there were specific charges made against Murray, there would be no grounds in asking for his resignation. An editorial in the Courier asked if the resolution was a “whitewash” or an “honest attempt to change conditions in the city?” The newspaper said while there was plenty of blame to be spread around, it remained optimistic about the city making a “new start.”

With the crisis of confidence eased, Murray continued to hunt for illegal stills. He was tipped off about a farm laborer acting suspiciously around a vacant barn on the Canet Ranch in Colonia Home Gardens. Loose floorboards were discovered in the barn. When several were removed, Murray found an underground den seven feet deep, 30 feet long and 10 feet wide. Inside was a huge double still and enough equipment “to make booze for the entire Southland.” Twenty gallons of freshly made booze and 14 barrels of mash were seized.

It was not uncommon for blind-piggers to use underground dens, but Ventura police had to admire the creativity of one bootlegger. While they searched the Garden Street home of a repeat offender, they could smell whiskey but couldn’t find anything. One officer moved a picture on the wall and discovered a cleverly constructed opening where liquor was stored. Moving the picture also triggered a device which dumped the booze into the drain. Officers reacted quickly enough to save enough liquor as evidence.

Battling the Rum Fleet

In 1925 authorities became concerned about their ineffectiveness in combatting a “rum fleet” operating in the international waters off the Southern California coast. The foreign-registered ships carried quantities of liquor from Scotland, Canada, and other countries. In May the Los Angeles Times reported the crew of the Coast Guard Cutter Tamaroa discovered a fleet of five ships 30 miles off Santa Rosa Island. The Tamaroa was hidden in the fog. At dawn, they watched the crews of the ships load hundreds of cases of liquor into two dozen speed boats. When the cutter was spotted, the speed boats scattered, and the larger ships put to sea. It was pointless for the Tamaroa to chase the small “mosquito” boats. The old cutter was soslow it was oftenreferred to as “the sea cow.” The contraband liquor was estimated to be worth $3 million, over $47 million today.

Patrolling the 42-mile Ventura County coastline was difficult if not impossible. There were many remote beaches and inlets for smugglers to hide. Favorite landing spots included Point Mugu, Oxnard, Hueneme, and Faria beach. Once ashore, bootlegging syndicates used cars, trucks, trailers, buses, even gasoline tankers and fertilizer trucks to move the liquor down the coast to Los Angeles in less than two hours. Profits were huge. A case of scotch sold at the ship for $50 would bring $25 a quart by the time it reached the city.

By the fall of 1925, the Coast Guard had transferred Commander L.C. Covell to the California coast. His successes on the east coast had earned him the nickname “The Rum Runners’ Nemesis.” His job was to stop liquor smuggling along the 500 miles of coastline from San Luis Obispo to the Mexican border. Commander Covell’s base of operation was a 51-year-old ice-smashing cutter the “Bear” which had last seen duty in the Arctic. He also had eight “persistent, unrelenting and tenacious” patrol boats capable of chasing down the smugglers’ mosquitos. Each had two high performance motors and a cannon, accurate to a range of 1000 yards, mounted on its bow. The U.S. signed treaties with 16 different countries during Prohibition that, while still upholding the principal of the three-mile limit, allowed searches on suspected smuggling ships anywhere within the distance from the coast that “can be traversed in one hour” based on the speed of the ship. For example, a ship capable of 10 knots could be searched up to 10 miles offshore.

The Demand for Christmas Liquor

Public demand for liquor traditionally grew at Christmas time. The International News Service estimated in November 1925 that liquor ships were waiting off the coast to unload $10 million worth of Christmas liquor, a staggering $157 million today. To stop rumrunners from flooding Southern California, sheriff’s deputies in Ventura, Orange and Los Angeles counties bottled up the roads leading to Los Angeles on November 23. Officers halted and searched every car at 14 roadblocks on major highways. Liquor seized ranged from one pint to 18 cases. Sixty people were arrested, and 23 cars were confiscated. Eighteen people were arrested in stops near the Ventura/Los Angeles County border on Ventura Boulevard near Calabasas, including a Ventura man. The 18 all had less than a quart of liquor and were given suspended sentences and their cars were returned. The major violators in the three-county crackdown were turned over to the feds for prosecution. One Christmas surprise was the popularity of bisque “Mama Dolls” – the kind that call “Mama” with eyes that open and close. Prohibition agents in Key West, Florida investigated after they found the dolls in a speakeasy raid. It was revealed that instead of excelsior stuffing, each doll contained a pint of real Spanish wine.

In 1926 the Coast Guard fired 59 rounds at a rum-running ship called the Grey Ghost on the seaward side of Santa Cruz Island. The Ghost was hit six times and ran ashore east of Valley Anchorage. The Coast Guard confiscated 200 “sacks” of imported whiskey and two half-barrels ofliquor.Sacks were packages holding six bottles jacketed in straw, three on the bottom, then two, then one, with the whole thing tightly sewn in burlap.

In February hammer-swinging Ventura County Sheriff’s deputies smashed more than 1,400 bottles of whiskey and a dozen cases of home brew and dumped it all into the gutter in front of the Ventura County Courthouse. Sheriff Clark and his men had conducted so many raids that the secure storage at the courthouse was too full and “there was hardly any room to move.” A few bottles were kept as evidence for pending cases. The deputies took advantage of a strong winter storm to flush the liquor into the sewer. A similar dumping in the past had ended badly when the liquor flowed down Courthouse Hill and stopped at Main Street.

Efforts began in May to federalize selected state, county, and municipal police officers to combat the illegal liquor trade. The program was tested in California under orders from President Calvin Coolidge. While Coolidge had personally opposed prohibition, he was committed to enforcing federal laws, and criticized the disobedient attitude of the public as a “failure to support the Constitution and observe the law.” Colonel R. E. Frith, the prohibition administrator for southern California began meeting with county sheriffs. Local police were deputized and trained with experienced federal agents. Frith said with their added authority, they would not only “assist their own departments to a more satisfactory degree, but…aid us whenever large conspiracies are detected.”

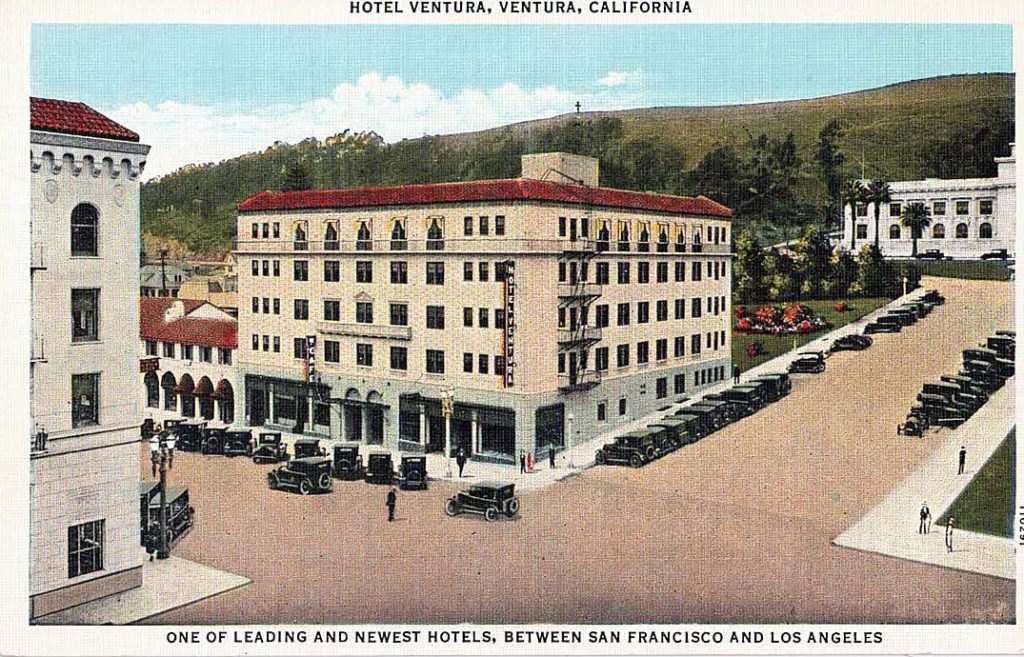

Police Raid Top Ventura Hotel

Proposition 9 appeared on the November state-wide ballot in 1926. It sought to repeal the Wright Act which enforced alcohol prohibition in California. It was defeated. Just days after the election, Ventura police staged what the Courier called “the most sensational raid in city history.” They arrived at the Hotel Ventura with a search warrant and confiscated 75 one-quart bottles of imported brand-name liquor. The hotel had been under surveillance for months. Police called it one of the “the most complete stocks of liquors ever found in one place in the county.” All of it was found in room 400 on the 4th floor of the hotel. Owner Gus Berg pleaded guilty to a charge of possession and paid a $500 fine. Despite his plea, Berg insisted he had no knowledge of the liquor stash and blamed one of his bellboys.

Another long investigation paid off just before Christmas when federal agents raided a Santa Cruz Island resort popular with summer vacationers. A well-known Santa Barbara Channel character, Ira K. Eaton, captain of the Sea Wolf, ran the island lodge. Agents found a dismantled, 100-gallon still buried under an oak tree in Eaton’s front yard. Three hundred gallons of moonshine were found throughout the lodge. Another 100 gallons was found aboard the Sea Wolf. Eaton made moonshine on the island, then took it to the mainland in small kegs where he sold it as “the real stuff just off the ship.”

Throughout 1928, Sheriff Clark made over 40 arrests in Ventura County’s greatest roundup of Prohibition violators. Many were tripped up in an undercover operation operated for several months out of a Hueneme garage run by Clark and his deputies. Two of the men arrested had reportedly transported more than a hundred gallons of alcohol in one run from Los Angeles to sell in Moorpark, Santa Paula, Fillmore and Piru.

While there was growing public demand for the repeal of Prohibition in 1929, federal enforcement became more severe. The Increased Penalties Act made most violations of the Volstead Act felonies. Even seeing someone violate the law and failing to report it was punishable by a three-year prison term. But by year’s end, much of the public’s attention had shifted to the economy when billions of dollars were washed away in just days during the October stock market crash.

Temperance Loses Its Appeal After the Big Crash

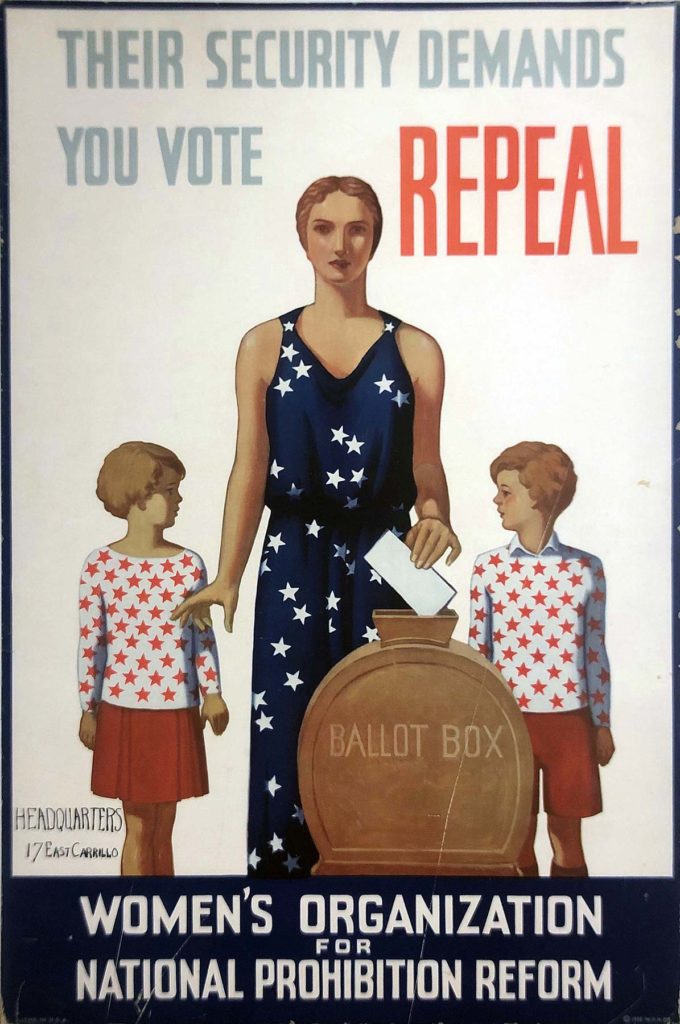

In 1930, The Literary Digest’s nation-wide poll found that 31% of respondents favored enforcement of Prohibition, 29% favored modification, and 40% favored its repeal. Addressing thousands of Quakers attending their annual conference in Whittier in June, Eva C. Wheeler, state president of Woman’s Christian Temperance Union pointed out that saloons had flourished in America for nearly 300 years, and she asked that prohibition, instead of being discarded after a mere decade, be given a 300-year tryout in the interest of fair play. Groups such as the Anti-Saloon and the National Temperance Council promised to oppose any repeal efforts. But social practices were changing.

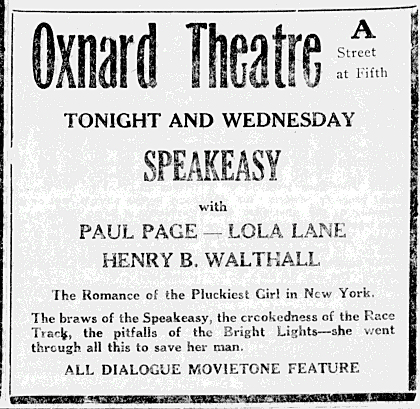

Hard liquor escalated in popularity. Cocktail parties and before-dinner drinks became commonplace. A commentary in the Courier noted that many people drank just “to beat the game.” The non-drinker came to be regarded as a drab, dull, unadventurous figure, out of style and apart from life. The production of home brew had become a national pastime. In Ventura County it was common to mix the strong “hootch” with Nehi lime soda. Speakeasys, bootleggers, and cocktails were the talk of the day. Serialized fiction appearing in the Chronicle was often set in speakeasies. An ad for the movie “Common Clay” at the Oxnard Theatre touted the story of a young woman struggling for respectability, “Men thought her a plaything. They pointed to her speakeasy days and court sentence to prove her frailty. But with her back to the wall, she is more than a match for men or courts of law.”

A major crackdown at the end of the year led to the arrest of 28 people and the seizure of 15 cars and five trucks in Ventura, Santa Barbara, and San Luis Obispo counties. In November and December, joint local and federal raids resulted in the seizure of over $60,000 in liquor, more than $1 million today. Despite enforcement victories, in 1932 The Literary Digest’s poll now showed 74% of the public wanted to repeal prohibition.

Prohibition and the 1932 Election

Prohibition was a dominant issue in the 1932 elections. Nearly every candidate for congress, state legislature and other offices in California’s August primary had declared a position on prohibition. At the summer presidential nominating conventions, the battle lines were drawn. The Democratic nominee, New York Governor Franklin D. Roosevelt promised repeal of the 18th Amendment. The incumbent President, Republican Herbert Hoover proposed a new, somewhat vague, constitutional amendment that satisfied no one. Also on the November 8th California ballot was another measure to repeal the state’s prohibition enforcement law.

On election night, people gathered in a storeroom next to the Oxnard Courier office. A local radio store, Carl’s Radio Den, had installed a large Zenith radio so the crowd could hear the returns. Messengers collected returns from the local precincts and shared them with the waiting crowd at the newspaper office. Record turnout was reported throughout Ventura County. In the end, too many voters blamed Hoover for the nation’s ills, including the Great Depression. Roosevelt became the first Democrat in 80 years to win an outright majority in both the popular and electoral votes. Normally conservative and Republican, California and Ventura County went to the Democrats. Statewide, the Wright Act was repealed by a two to one margin. After the election, a Courier editorial emphasized, “Voters were interested only in one thing. To elect Democrats and to vote wet. Personalities or merit went for nothing.”

Prohibition Ends After 13 Years

On December 6, 1932, Senator John J. Blaine introduced the Blaine Act. It enabled states to ratify the 21st Amendment to repeal national Prohibition. It quickly passed both houses of Congress and was sent to the states for ratification. California ratified the amendment on July 24, 1933. On the afternoon of December 5, 1933, Utah became the 36th state to ratify the 21st amendment ending prohibition after 13 years. Los Angeles restaurants and night clubs arranged for extra entertainment after a heavy demand for reservations. Harry Moore, the Ventura County representative on the State Board of Equalization stressed that beer, wine, or other liquor sellers needed a state license to operate. The repeal of the Wright Act had taken liquor sales licensing away from cities and counties and put it into the hands of the state. Theodore J. Roche, director of the State Motor Vehicle Department expressed hope that California motorists would use “their new-found liberties with sanity and wisdom” and warned drunk driving would not be tolerated. By 1933, more than two million cars were registered in California, three times the number in 1920.

A Courier editorial reminded readers that “after all, liquor is not the only issue confronting the American people.” Nor is it the “complete obsession as it often seemed during the prohibition era.”The editors concluded, “temperance already has a better start in the United States than some extremists have thought.”

Make History!

Support The Museum of Ventura County!

Membership

Join the Museum and you, your family, and guests will enjoy all the special benefits that make being a member of the Museum of Ventura County so worthwhile.

Support

Your donation will help support our online initiatives, keep exhibitions open and evolving, protect collections, and support education programs.

Bibliography

- “1926 Calvin Coolidge – Prohibition Enforcement.” State of the Union History. Last modified September 19, 2015. https://www.stateoftheunionhistory.com/2015/09/1926-calvin-coolidge-prohibition.html.

- “‘Bootleg Hooch’ Held Appeal of the Forbidden.” Accessed November 4, 2021. https://archive.vcstar.com/entertainment/bootleg-hooch-held-appeal-of-the-forbidden-ep-364424093-352291791.html/.

- “Chinese Pioneers of Ventura County Subjects of New Museum Exhibit.” Accessed November 4, 2021. https://archive.vcstar.com/lifestyle/chinese-pioneers-of-ventura-county-subjects-of-new-museum-exhibit-ep-363223143-351993351.html/.

- Clark, William P. “Oral History Interview with William Petit Clark.” By Mary D. Johnston/Museum of Ventura County. October 12, 1979.

- “KKK and WCTU: Partners in Prohibition.” Potsdam State University of New York. Last modified February 23, 2013. http://www2.potsdam.edu/hansondj/Controversies/KKK-and-WCTU-Partners-in-Prohibition.html.

- The Los Angeles Times. “Fair Play for Dry Act Urged.” June 26, 1930.

- The Los Angeles Times. “Firth Acts on Dry Plan.” May 25, 1926.

- The Los Angeles Times. “How “Wasp” Fleet Harries Rum Ships.” December 27, 1925.

- The Los Angeles Times. “Huge Rum Row Off Southland.” May 12, 1925.

- Mayer, Jonathan. “The Wine Vote, Why California Went Dry.” The California Supreme Court Historical Society. Last modified 2013. https://www.cschs.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/03/CSCHS_2013-Mayer.pdf.

- Oxnard Daily Courier. “”Mama Dolls” Filled With “Kick” Liquid.” February 2, 1924.

- Oxnard Daily Courier. “Airplane Booze-Runners Stopped Here on Way North.” April 28, 1922.

- Oxnard Daily Courier. “American Temperance.” December 8, 1933.

- Oxnard Daily Courier. “Beer In Museums.” November 30, 1920, 2.

- Oxnard Daily Courier. “Big Cargo Drifts in Near Hueneme.” October 1, 1925.

- Oxnard Daily Courier. “Booze Crooks Try to Trick Santa Paula Woman.” July 18, 1921.

- Oxnard Daily Courier. “Booze In Big Quantities in Custody of U.S.” September 11, 1922.

- Oxnard Daily Courier. “Both Parties Claim California, Election Returns Tonight.” November 8, 1932.

- Oxnard Daily Courier. “Calif. Laws Not Changed by Wright Act.” December 28, 1922.

- Oxnard Daily Courier. “California Wine Going to the Orient.” January 15, 1920.

- Oxnard Daily Courier. “Chief Murray Wants Square Deal in Fight.” February 18, 1924.

- Oxnard Daily Courier. “Chief Murray Warns Property Owners on Bootlegging Renters.” March 29, 1923.

- Oxnard Daily Courier. “City Attorney Holds It Would Be Illegal to Refund License.” April 14, 1920.

- Oxnard Daily Courier. “Confiscate Cars at County Line.” November 23, 1925.

- Oxnard Daily Courier. “County Officers May Search Cars.” December 29, 1922.

- Oxnard Daily Courier. “Democrats Staking All on Repeal.” June 30, 1932.

- Oxnard Daily Courier. “Dew Drop Inn at Camarillo Closed.” September 29, 1921.

- Oxnard Daily Courier. “Duval’s Fine Run.” November 10, 1932.

- Oxnard Daily Courier. “Enforcement of Liquor Law Will Be Rigid.” December 5, 1933.

- Oxnard Daily Courier. “Fifteen Bootleggers Nabbed in Biggest Raid on Booze Joints Ever Staged in Oxnard History.” February 9, 1924.

- Oxnard Daily Courier. “First a Bootlegger Then the Undertaker.” August 13, 1923.

- Oxnard Daily Courier. “Five Billion Washed Away.” October 28, 1929.

- Oxnard Daily Courier. “Foil Huge Coastal Liquor Plot.” May 7, 1928.

- Oxnard Daily Courier. “Had Cleverest Hiding Place for His Liquor.” December 1, 1924.

- Oxnard Daily Courier. “Island Resort Raided by Drys, Eaton Arrested.” December 20, 1926.

- Oxnard Daily Courier. “Just a Beginning.” February 27, 1924.

- Oxnard Daily Courier. “May Be Legal to Buy Liquor Tomorrow P.M.” December 4, 1933.

- Oxnard Daily Courier. “Meeting of Citizens Formulates Demand for Enforcement of Local and State Laws Upon Officials.” February 11, 1924.

- Oxnard Daily Courier. “Nab Ringleaders of Powerful Liquor Gang.” May 16, 1928.

- Oxnard Daily Courier. “Nearly 1500 Bottles of Booze Smashed in Ventura by Sheriff.” February 3, 1926.

- Oxnard Daily Courier. “Not Many Changes in Saloons at First to Be Made Here.” January 15, 1920.

- Oxnard Daily Courier. “Peter H. Kapp Arrested in Federal Raid.” August 10, 1923.

- Oxnard Daily Courier. “Politically Speaking.” June 24, 1932.

- Oxnard Daily Courier. “Private Meeting of Trustees Tomorrow.” February 25, 1924.

- Oxnard Daily Courier. “Prohibition Enforcement.” September 20, 1920, 2.

- Oxnard Daily Courier. “Prohibition Helps Theaters.” May 10, 1920.

- Oxnard Daily Courier. “Raiders Seize Liquor Worth Over $60,000.” January 10, 1931.

- Oxnard Daily Courier. “Roosevelt’s State Total Grows.” November 9, 1932.

- Oxnard Daily Courier. “Sheriff’s Raid Nets 7 Arrests.” March 30, 1920.

- Oxnard Daily Courier. “Smart to Be Legal.” November 29, 1933.

- Oxnard Daily Courier. “Sobriety and Scrubbing.” June 21, 1920, 2.

- Oxnard Daily Courier. “Some Dry Leaders Must Have Liquor.” December 8, 1920.

- Oxnard Daily Courier. “The Anti-Dry Reaction.” March 15, 1920, 2.

- Oxnard Daily Courier. “Trustees Pledge Themselves to Law Enforcement At Meeting in Bank With Prominent Citizens.” February 26, 1924.

- Oxnard Daily Courier. “Ventura’s Leading Hotel in Biggest Raid; Owner Fined.” November 6, 1926.

- Oxnard Daily Courier. “What County Thinks of Oxnard.” February 12, 1924.

- Oxnard Daily Courier. “Will Release All Nabbed for Booze.” November 24, 1925.

- Parr, Robert J. “Oral History Interview with Robert J. Parr.” By Georgeanna Holland/Museum of Ventura County. November 16, 1979.

- “Prohibition in America (U.S.): Timeline.” Alcohol Problems and Solutions. Last modified September 26, 2021. https://www.alcoholproblemsandsolutions.org/prohibition-in-america-u-s-history-timeline/.

- “Repeal in America: 1933 – Present.” Alcohol Problems and Solutions. Last modified September 26, 2021. https://www.alcoholproblemsandsolutions.org/repeal-america-u-s-timeline-history/.

- Smith, Burton. “Cowboy Is Multimillionaire.” The Los Angeles Times, February 5, 1922, 15.

- Stanford, Sally. The Lady of the House; the Autobiography of Sally Stanford. New York: Putnam, 1966.

- “The Three Mile Limit: Booze on Boats.” In the Spirit of the Law. Last modified November 27, 2019. https://inthespiritofthelaw.com/2019/11/27/the-three-mile-limit/.

- Thulin, Lila. “What Caused the Roaring Twenties? Not the End of a Pandemic (Probably).” Smithsonian Magazine. Last modified May 3, 2021. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/are-we-headed-roaring-2020s-historians-say-its-complicated-180977638/.

- Ventura Free Press. “Decisive Majority Settles the Saloon Question in Ventura For All Time.” September 26, 1913.

- Ventura Free Press. “Saloons Close October 10th.” October 3, 1913.

- Wheeler, Eugene D. Shipwrecks, Smugglers and Maritime Mysteries. Ventura, CA: Pathfinder Publishing, 1986.

- Yerger, Rebecca. “Rebecca Yerger, Memory Lane: Jackass Brandy and Other Prohibition Tales.” Napa Valley Register. Last modified September 15, 2021. https://napavalleyregister.com/lifestyles/real-napa/columnists/rebecca-yerger/rebecca-yerger-memory-lane-jackass-brandy-and-other-prohibition-tales/article_29974f22-f89c-5318-ac71-ccb8a908cdea.html.