By Library Volunteer Andy Ludlum

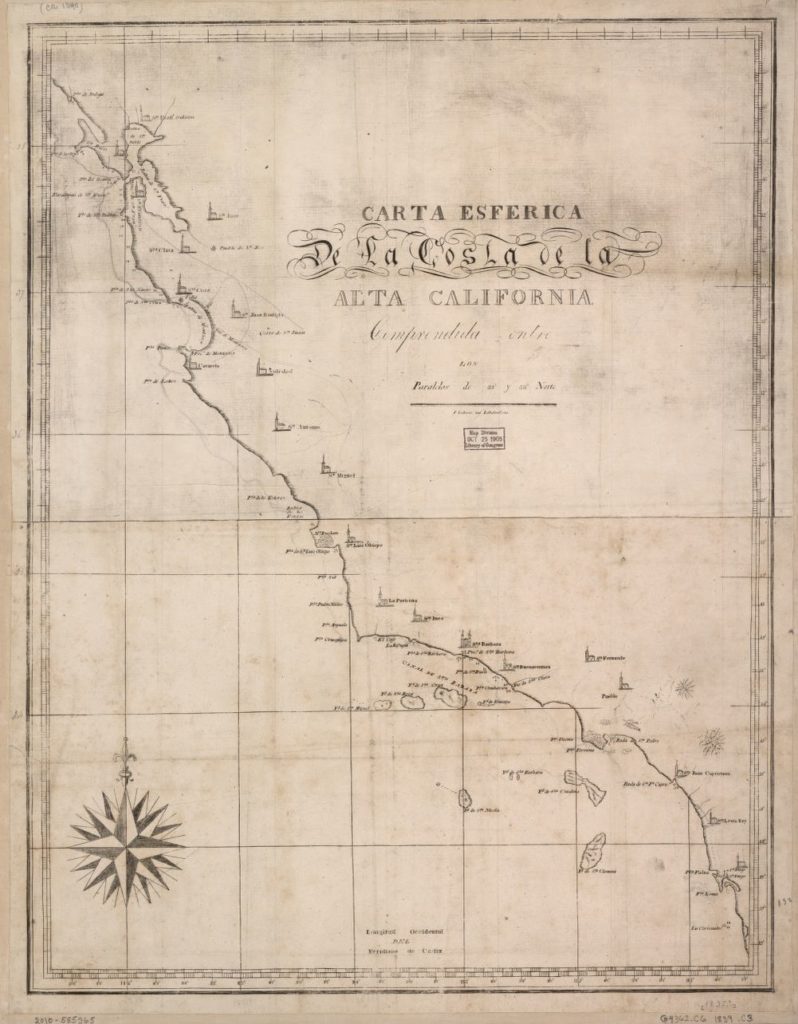

When two pirate ships appeared off the California coast in November 1818, it was a moment the governor of the Royal Presidio of Monterey had been dreading for six weeks. He had been warned that Hippolyte Bouchard, a ruthless Argentine pirate, had set his sights on Monterey believing there was gold and other treasures hidden in California’s Spanish missions. And strange as it may sound, the appearance of the ominous ships triggered events that led to a mother’s tragic loss on a hill above Mission San Buenaventura.

Patriot or Pirate

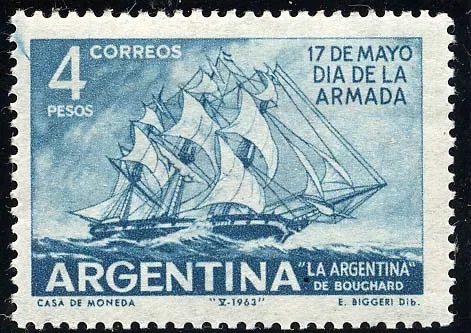

To put the story in context, we first must understand the circumstances that brought such a notorious pirate to California. Bouchard was as much a professional revolutionary as he was a pirate. He was born in France in 1780. He had served in the French naval campaigns against the English. But he became disillusioned with the direction of the French Revolution and went to Argentina to fight in the May Revolution of 1810. The once-expansive Spanish empire was in decline. The French, under Napoleon had taken back the Louisiana Territory and sold it to the United States in 1803. Starting with Mexico in 1810, independence movements sprang up over the next 11 years in the Spanish colonies of Paraguay, Uruguay, Argentina, Chile, and Peru.

Bouchard joined the Mounted Grenadiers Regiment led by José de San Martín and took part in the Battle of San Lorenzo in 1813. There he captured a Spanish flag and as a reward, was granted citizenship by the free state of the United Provinces of Rio de la Plata, a direct ancestor of the Argentine Republic. The Argentine revolutionaries had no navy to attack Spanish ships, so they turned to privateering. A privateer was someone given a commission from a host country to wage war by fighting and capturing enemy ships as prizes. Depending on the point of view, a privateer was either a patriot or a pirate. Bouchard’s new country gave him a commission in 1815. One of the first Spanish ships that Bouchard captured, a deep draft frigate, was refitted and renamed La Argentina. This would be Bouchard’s flagship in 1817 when he began his two-year, round-the-world voyage targeting Spanish merchant ships.

Pirates Attack the Monterey Presidio

The presidio or “royal fort” had been strategically placed at the southern end of Monterey Bay and was charged with protecting ports, missions, and other Spanish interests in its region. Due to the crumbling Spanish empire, the royal fortress had decayed into a forgotten outpost. Living conditions for the settlers and soldiers were damp, crowded, and unsanitary. Soldiers were paid infrequently if at all. The presidio was not self-sufficient and relied on supply ships from Mexico.

In theory, the presidio maintained a garrison of 90 men for its defense, although half of its soldiers were elsewhere, guarding the missions within Monterey’s jurisdiction. On November 20, when the lookout at Point Pinos sighted the two pirate ships, the governor issued orders to all neighboring militiamen to gather at the presidio. He had just 40 men to face the pirates, 25 from the presidio’s troops, four old artillery men, and 11 militiamen.

In addition to La Argentina, Bouchard’s force included a smaller warship, the Santa Rosa, commanded by an English seaman named Peter Corney. Together they had a crew of 360 sailors and carried 52 cannons.

As well as being outmanned by the pirates, the presidio was outgunned. The fort’s artillery battery, El Castillo, was located on a hill to the west of the harbor. It had ten cannons and plenty of cannon balls but was generally described as “a miserable battery.” But thanks to the advance warning, the governor had time to build a second gun battery, El Mentidero, along the beach. As the pirates entered Monterey Bay under the cover of darkness, they had no idea the second gun emplacement was waiting for them.

In 1818, the presidio had a population of about 400. Most of the settlers on the Monterey peninsula either lived in the presidio or at the mission in Carmel. A small group of Spaniards stayed behind to fire the cannons. Women, children, and men unable to fight were sent to the presidio’s Rancho del Rey San Pedro near Salinas.

The pirates feared the deep frigate La Argentina might run aground, so they used the smaller Santa Rosa to press the attack. The ship anchored so far into the harbor that the hilltop guns of El Castillo could only reach the highest parts of the Santa Rosa’s masts. With nothing to fear from El Castillo, the captain waited until it was light enough to make out targets and began firing on the larger buildings in the presidio. But now the beach-front battery, El Mentidero, opened fire, surprising and trapping the Santa Rosa. If it moved away from the shore, it would be exposed to fire from El Castillo. Quickly the Santa Rosa suffered crippling damage along the waterline.

The Santa Rosa surrendered and the firing stopped. They moved all the cannons to the undamaged side of the ship to raise the damaged side higher out of the water. The crew then jumped into the lifeboats and rowed towards La Argentina which was waiting safely out of range.

Bouchard watched the scene in horror. “After seven rounds of fire I saw with disgust our flag being lowered and people escaping in boats toward my ship.” Five pirates were dead, while the Spanish suffered no casualties.

The next day, still enraged and embarrassed by his defeat, Bouchard sailed a couple miles up the coast where he landed a force of 200 men with mounted cannons. The force quickly captured El Castillo by attacking it from behind. He then opened fire on the presidio. The Spaniards could only resist for an hour. The governor and his men had to abandon the presidio and retreat to the ranch near Salinas. Jubilant pirates began stealing cattle and taking everything of value that they could carry. They set fire to the houses along with the fort, the artillery headquarters, and the governor’s residence. Only the Royal Presidio chapel was spared. Bouchard destroyed El Castillo’s cannons by loading them, burying them barrel-down halfway into the ground, then firing them. The Argentine flag flew over Monterey for six days. Bouchard recovered and repaired the damaged Santa Rosa and sailed south out of Monterey on November 29.

Coastal Presidios and Missions Alerted

The Spanish network along the coast mobilized for further attacks. Lookouts were posted at twenty-five strategic locations. All presidios, missions, and pueblos were put on high alert. Coastal missions like Santa Cruz were evacuated.

The pirates would strike next about twenty miles from Santa Barbara. They anchored off Refugio Canyon and landed near the Ortega Family rancho. They took all the food, killed the cattle, slit the throats of the saddle horses in the corrals and burned the farm. Bouchard then moved on to Mission Santa Barbara. The padres had only a small group of armed and trained converts. But with a clever ruse, they convinced Bouchard the mission was heavily defended. In reality, what Bouchard saw through his spyglass was the same small group of men changing uniforms behind bushes to make it look as if there were more of them. Bouchard sailed out of the harbor without attacking. A rider had been dispatched to Mission San Buenaventura after Bouchard looted the Ortega rancho with a warning that the mission at San Buenaventura could be next.

Mission San Buenaventura Evacuated

Mission San Buenaventura was the 9th of the 21 Franciscan missions and in 1782 was the last of the missions founded by Father Junipero Serra. The mission was built on Chumash land. The village of Shisholop was located less than a mile south of the mission compound. When Serra and the Spanish met the Chumash, their territory stretched along the coast from Malibu to San Luis Obispo. Their sophisticated culture, social systems, trade, and commerce influenced what is now the central coast of California as well as the Santa Barbara Channel Islands.

The Spanish expected the Chumash people would provide the labor to build the mission. The relationship between friars and the Chumash remains highly controversial. In 1773, the Viceroy of New Spain, Antonio Maria Bucareli decreed that “the government, control and education of the baptized Indians should belong exclusively to the missionaries.” This highly paternalistic view stipulated that there would be supervision “in all economic affairs as would a father of a family regarding the care of his household, and the education and correction of his children.”

Conversion was voluntary and in fact most of the Chumash decided against Christianity. However, once they had accepted religion, they were no longer free to change their minds. The friars saw conversions as binding contracts and should a convert run away, he or she would be forcibly returned. Repeat escapees were put in stocks or beaten. In 1818 over 1,300 Chumash converts lived a predictable life at the mission regulated by a bell ringer signaling times for worship, work, meals, recreation, and sleep. They planted crops and raised cattle, making the mission self-sufficient.

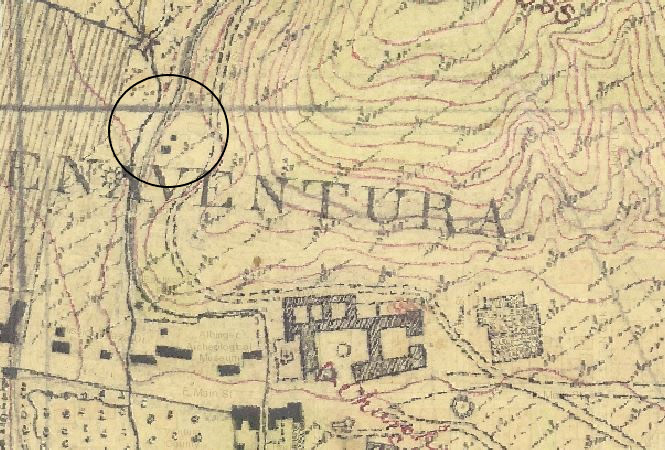

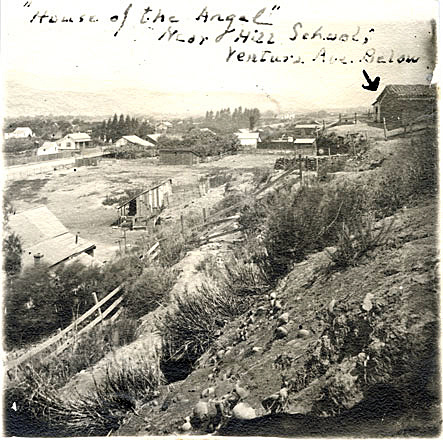

Mission San Buenaventura was not designed as a military outpost, but rather as a “fortress of faith.” But its location near the entrance to the Santa Barbara Channel was clearly strategic. In fact, Father Serra believed the location was better suited than San Diego, Santa Barbara, Monterey “or any other place we have so far discovered.” The mission had been threatened in the past by various marauders. Some came down to the sea by way of the Ventura River canyon, others came along the Santa Clara Valley. When the original mission church was moved further inland to its present location to avoid destructive storm surges and flooding, it was decided to build barracks on the hillside behind the church and train some of the converts as soldiers. They lived in the barracks with their wives and children. The final step of the defensive plan was to build a sentry house about 10 yards northwest of the barracks. This tiny adobe was just high enough on the hill to give mission defenders a good view to the north. According to the story, among those living in the barracks were Juana and Miguel Basilia, both members of the Chumash tribe. They had taken Spanish names when they converted to Christianity. Juana was a new bride of just a year and was said to be the best basket-maker at the mission.

The news of the pirates pending arrival sent the mission priests into panic and frenzy. They had to act quickly, but what could be done? Surely, they were no match for well-armed pirates with ships and cannons. They decided it was better to abandon the mission and flee to the hills than face the murderous pirates. The mission’s livestock, food, and any valuables they could carry were to be taken along.

Miguel was put in charge of an advance team that would march about five miles inland and upstream along the Ventura River to the Santa Gertrudis Asistencia. The asistencia or “sub-mission” had been used in the past during times of crisis. The padres and their converts would wait at Santa Gertrudis until the pirates had come and gone.

Young Woman Left Alone

Juana was supposed to join the main group leaving the mission. But the evacuation was slowed by chaos and confusion. Finally, a long, straggling line of people began to wind northward along the mission water ditch into a canyon leading to the hills. But Juana wasn’t among them. The young woman found herself alone on the hillside overlooking the sea where the pirates might appear at any moment. As darkness approached, Juana went into the little adobe sentry house to rest on a rough couch and pray to the Virgin Mary for advice. She hoped Miguel would come back for her.

The only account of the story is unclear at this point. Juana did not rest for long. She was pregnant and went into labor. There are no further details of what was a difficult, unassisted delivery. When Miguel discovered Juana was not with the main group, he retraced the route and found her unconscious with her arms around her dead baby. When Miguel was finally able to rouse her, he told her she was safe as the pirates had not come. She fell back asleep and awoke sobbing at daybreak.

A tiny grave was dug in the floor of the little adobe. Miguel and Juana wound their first-born in a traditional Chumash shroud made of a marsh plant used in basketmaking and sewn with grasses. Then with Christian prayers, the little body was placed in its final resting place. From that day, the little adobe sentry house became known as the “House of the Angel.” Children would cross themselves when passing the place.

While the pirate Bouchard passed by Mission San Buenaventura, he did attack one last time in California, at San Clemente where the padres had also been warned about his arrival. They had time to take any valuable church artifacts away from the mission. Frustrated once again, Bouchard burned the storehouse, the soldiers’ barracks, and the governor’s house and sailed away.

Pirate Meets a Violent End

After his raid on the California coast, Bouchard went to Peru to fight in its war of independence. It was in Peru that his naval career was most successful, and he rose in rank to Vice Admiral. In reward for his services, the Peruvian government gave Bouchard two ranches. Upon retirement, he opted to stay in Peru. He ran his ranches and a sugar mill with slave labor. In 1837 the local papers reported Bouchard “was suddenly killed by his own slaves two nights ago…for which reason he did not express his last will nor did he receive any sacraments.” He was 57 years old.

The story of the little adobe was passed on over the years. Children attending the Hill School, which was built on the hill 55 years later in 1873, would drop their voices to a whisper and point at the little adobe and say to one another, “that is the House of the Angel.”

Second Life for the House of the Angel

The little adobe did have one other life of note. Around the end of the Civil War, it became the secret meeting place for Ventura Republicans. Much of Southern California had been settled by people from the southern states. There were few Republicans in Ventura and in 1864 to be associated with the “Party of Lincoln” was unpopular if not dangerous. The first Republican club had grown out of a secret association of Union sympathizers called Freedom’s Defenders. They would hold their meetings in the old adobe. Reportedly, their meetings took on an air of mysticism with secret passwords, special grips, and hand signals.

Over the years, the adobe structures surrounding the mission were torn down. The account of the House of the Angel was written by E.M. Sheridan, the first curator of what would become the Museum of Ventura County. While he presented it as fact, not legend, Sheridan’s story was written more than 110 years after the events, around 1930. By then the Hill School was gone and Sheridan was one the few people alive who had even seen the ruins of the little adobe. Fact or legend, without Sheridan’s account, the story of the House of the Angel might have been lost.

Make History!

Support The Museum of Ventura County!

Membership

Join the Museum and you, your family, and guests will enjoy all the special benefits that make being a member of the Museum of Ventura County so worthwhile.

Support

Your donation will help support our online initiatives, keep exhibitions open and evolving, protect collections, and support education programs.

Bibliography

- “The Attack on Monterey – Meet the Argentine Privateer Who Captured Spain’s California Capital.” MilitaryHistoryNow.com. Last modified September 5, 2016. https://militaryhistorynow.com/2016/09/05/the-attack-on-monterey-meet-the-argentine-privateer-who-captured-spains-california-capital/.

- “The Good Pirate.” Welcome to the California Missions Resource Center | California Missions Resource Center. Accessed August 8, 2021. https://missionscalifornia.com/stories/good-pirate.

- “Hipolito Bouchard and the Raid of 1818.” Accessed August 8, 2021. http://mchsmuseum.com/bouchard.html.

- “Hippolyte Bouchard.” Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia. Last modified May 16, 2004. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hippolyte_Bouchard.

- Kamiya, Gary. “When Argentina Attacked Monterey: Part I.” San Francisco Chronicle. Last modified November 11, 2017. https://www.sfchronicle.com/news/article/When-Argentina-attacked-Monterey-Part-I-12348567.php.

- Knecht, Robert L. “When Pirates Attacked California: The Refugio Bay Pirate Cache.” The Astorian. Last modified December 6, 2018. https://www.dailyastorian.com/news/when-pirates-attacked-california-the-refugio-bay-pirate-cache/article_a5501668-cb73-5b8a-b9e1-06937e093216.html.

- “Moments in Time: The Continuing Story of Hipolito Bouchard.” The Capistrano Dispatch. Last modified September 28, 2018. https://www.thecapistranodispatch.com/the-continuing-story-of-hipolito-bouchard/.

- Sheridan, Edwin M. “The Story of the “House of the Angel”.” In Historical Writings, 1920s and 1930s. Ventura: Compiled by Yetive M. Hendricks, 1993.

- Sheridan, E. M. “Early County Republicans Unpopular; Met in Secret.” Ventura County Star, November 25, 1929.

- “Spanish Empire.” Info:Main Page – New World Encyclopedia. Accessed August 8, 2021. https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Spanish_Empire.

- Stickel, E. Gary. San Buenaventura Mission Archaeological Excavations. Los Angeles: Environmental Research Archaeologists, 1997.

- Weber, Francis J. The Mission by the Sea. A Documentary History of San Buenaventura Mission. Los Angeles: Archdiocese of Los Angeles, 1978.