By Phil Brigandi

Post edited by Krystell Jimenez, Project Archivist

In this special edition of Journal Flashback we present excerpts from an article in the 1998 double issue of the Ventura County Historical Society Quarterly (Volume 42, Issues 3 & 4). Titled “The Rancho and the Romance: Rancho Camulos and the Home of Ramona”, the article by Phil Brigandi* examines the complexities of the 1884 novel Ramona by Helen Hunt Jackson and how the novel’s popularity coincided with large-scale changes in transportation. New railroad lines in the region allowed for an influx of tourists enamored with a way of life that no longer existed in California and with romanticized images of Californios and the ranchos. The author expertly analyzes how it both shaped perceptions of California and Californio identity. All footnotes are the original author’s unless otherwise stated.

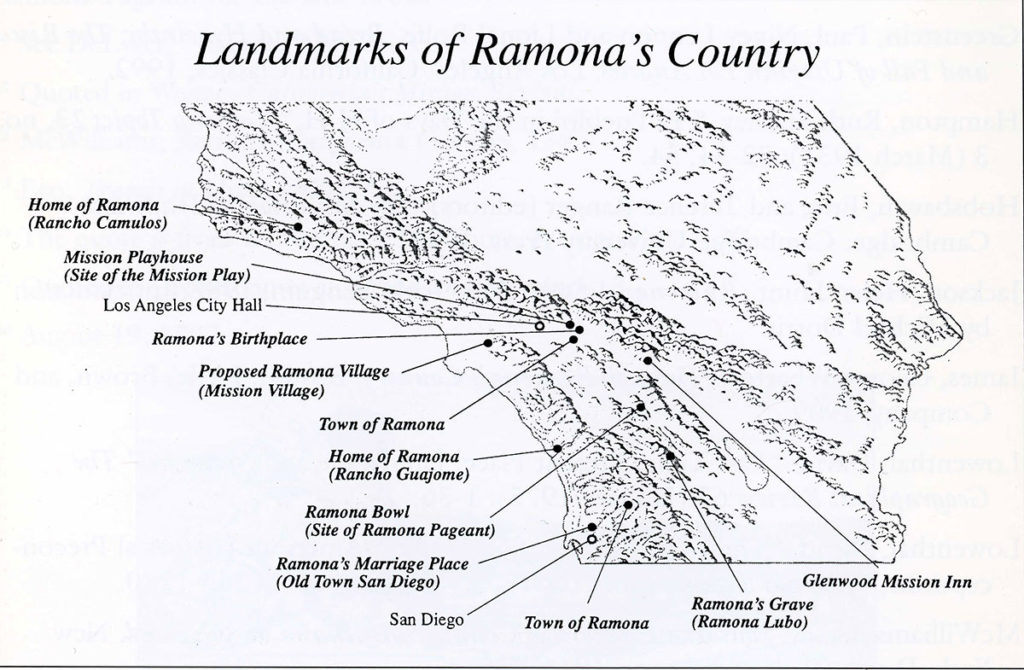

For those unfamiliar with the novel, Ramona is set in Southern California – the author is vague on the specific location. It takes place after the Mexican–American War and the titular character is a mixed-race young woman of Scottish and Native American descent named Ramona.1 She is taken in by a wealthy Mexican ranching family, the matriarch of which, Señora Moreno, is harsh and controlling. Ramona elopes with Alessandro, the son of Pablo Assís, the head of his tribe from Temecula.2 The two experience continuous racial discrimination as they are driven from place to place due to the influx of American settlers.3 Alessandro, who suffers from an unspecified mental illness, is killed by an American settler. Felipe, the son of Señora Moreno, then finds Ramona and brings her back to the ranch, where he marries her and she lives out her life.

In his article, titled “The Rancho and the Romance. Rancho Camulos: The Home of Ramona”, Phil Brigandi states:

No one book has had as much impact on Southern California as Helen Hunt Jackson’s 1884 novel, Ramona. Written to try to change public opinion towards the treatment of America’s Indian4 people, instead Ramona was swept up into Southern California’s growing tourist industry and helped to fuel a mythical image of California history that is still with us today.5

The Ramona Myth (as it has been called) did not so much grow out of the novel itself as out of the tourist industry that capitalized on Ramona’s popularity.6 It cannot be stated too clearly (or too often) that the story of Ramona is fiction, but it was appropriated almost immediately by promoters who did not care whether it was true or not; they only knew that it was good for business. The more tourists Ramona brought to Southern California, the more local promoters tried to capitalize on its fame. Nowhere has the line between fact and fiction been blurred more than at the Rancho Camulos, near Piru in Ventura County.

The Rancho Camulos is actually only the remnant of the Rancho San Francisco, which was granted to Antonio del Valle in 1839.7 After his death in 1841, Antonio’s son, Ygnacio del Valle (1808-1880), took control of the rancho. The del Valles continued to live in Los Angeles until 1861, when they finally moved to Camulos.

Brigandi recounts how Helen Hunt Jackson arrived in Southern California in 1881 in order to write for Century magazine, an interesting episode in which she was introduced to Antonio Coronel:

[A] Mexican pioneer who had come to California as a teenager in 1834. He had devoted the last years of his life to preserving the history and traditions of his adopted homeland. He had a ready supply of stories, which he told in Spanish while his young wife, Mariana, translated for Jackson.8It was apparently the Coronels who first suggested to Jackson that if she wanted to see a good example of an old Mexican rancho, she should visit Camulos.9 On January 22, 1882, while on her way from Los Angeles to Santa Barbara, Jackson made her first and only visit to Camulos. A week later, on January 30, 1882, she wrote to the Coronels: “You will perhaps have heard that I was so unfortunate as not to find Mrs. del Valle at home, so I only rested two hours at her house and drove on to Santa Barbara that night. I saw some of the curious old relics but the greater part of them were locked up and Mrs. del Valle had the keys with her.10”

Brigandi’s article belies the fact that Don Antonio F. Coronel was a prominent Californio politician who served as mayor of Los Angeles in 1853-54. He is often credited as Los Angeles’ first preservationist. His wife Doña Mariana W. de Coronel was a Tejana from the Los Brazos River area who collected Indigenous and Mexican curios. Brigandi’s article also includes photographs of Coronel and his wife acting out “old fiestas” in costume on the veranda of their house for a photographer in 1888. While this episode is gone over rather quickly, it does hint at an interesting complicity of Mexican-Americans and Chicanx peoples in providing depictions of Mexican culture and customs for white audiences. In fact, in a footnote Brigandi states that Jackson suspected Coronel was “playing the part.” The novel is one in which pre-American Mexican life in California is largely romanticized, but both the novel and the subsequent tourist craze are largely the work of white voices. The role that Coronel and his wife played in both preserving Mexican-American life and history in Los Angeles, as stated by Brigandi, and in performing “Mexicaness” for white audiences hungry for authentic but idealized depictions hints at the difficult line Coronel must have had to walk. It also suggests ways in which Californios and other Mexican-Americans may have sought to emphasize their Spanish identity and played on ideas of noble Spanish lineage in order to counter Anglo prejudices. And for all of the wryness in Jackson’s comment about Coronel playing the part, in a footnote Brigandi quotes a letter in which she refers to the family at Camulos being “as Mexican and un-American as heart could wish.” It points to the trap of Chicanx people being both accused of inauthenticity when “playing Mexican” and expected to and even applauded for fulfilling the role – all while overlooking the role white gaze plays in this story.

Regarding Camulos, Brigandi states:

If Jackson was particularly struck by Camulos, she does not say so in her letter. In fact in the next paragraph she writes that “the most interesting part of my journey” was her visit to Mission San Fernando, which she describes at some length. Camulos was not really a typical old Mexican rancho in Jackson’s day. The del Valles had been forced to sell most of their land after the drought of 1863-64. When all the sales and partitions were over, Ygnacio del Valle was left with only 1,344 acres of the former 48,000-acre rancho. Even the del Valle’s 20-room adobe home had been built after statehood, with most of the construction done in the 1860s, and even some in the [18]70s.

To keep Camulos alive, the family had switched from grazing cattle and sheep to farming. The ranch became widely known for its wines and brandies, and a large two-story brick winery had been built alongside the adobe around 1871. The del Valles also grew oranges, almonds, grapes, wheat, corn, beans and olives, and made an unsuccessful attempt at growing pomegranates. There were still a few sheep on the rancho at the time of Jackson’s visit, but not like the old days.

Three years prior to Ramona, Jackson had written A Century of Dishonor, which is a nonfiction chronicle of Indigenous peoples’ experiences with the U.S. government. Jackson emphasized the many injustices perpetuated by the U.S. government. Brigandi writes that Jackson was interested in reform of government policies toward Indigenous peoples. He says:

Jackson visited several other ranchos during her tour of Southern California, and a number of Indian villages. Up to that time, her knowledge of the Indians and their plight had come mostly from books and government reports.11 In Southern California, she saw with her own eyes the conditions they were living under and heard their sad tales with her own ears. Whole villages had been dispossessed. Violence against the people often went unpunished. The reservations were poorly located, poorly surveyed, and poorly supplied.

Jackson was already a vocal advocate of Indian reform; now she turned her attention toward Southern California’s Indians. She managed to secure a commission from the government to write a report on the Indians of Southern California for the Department of the Interior, and returned in 1883 to visit as many villages and reservations as she could. Abbot Kinney, later the founder of Venice, California, traveled with her as co-commissioner, but it was Jackson who wrote their graphic final report.

Jackson’s Report on the Conditions and Needs of the Mission Indians (as Southern California’s native people were usually called at the time) is a straightforward, forceful account of what Jackson saw and heard. Yet its recommendation fell mostly on deaf ears.12

Jackson’s intention in writing the novel was to highlight discrimination against Indigenous peoples. She hoped that framing it as a romance novel would allow her to reach readers who would otherwise ignore the issue. In a letter to the de Coronels she said, “People will read a novel when they will not read serious books.”13 It is important to remember that during the time Jackson was writing the novel, the Office of Indian Affairs was actively kidnapping Indigenous children from their families, and residential school attendance was made compulsory in 1891. Despite common perceptions, Jackson actually worked on the novel in Colorado Springs, Colorado, and in New York City during the winter of 1883-84. It was published in serial form in Christian Union on May 15, 1884, and then as a book by Roberts Bros. that November.14 For those curious and wanting to know more, her papers can be found at the New York Public Library and Colorado College.

According to Brigandi, the novel did not have the intended effect. It did not change public opinion on the U.S. government’s policies. It was well-received, but as a romantic and sentimental portrayal of Californio life. Brigandi also highlights the role that the 1880s real estate boom and railroad expansion played in the influx of Ramona tourism:

The timing of Ramona partly explains what happened next. In the late 1880s Southern California experienced its most frantic real estate “boom,” brought on by the arrival of the Santa Fe Railroad. New towns and subdivisions covered the land, and tourists from throughout the United States began to discover Southern California—and Ramona became their guide.

When tourists and new residents began arriving in Southern California many went looking for the places they’d read about in the story. And where there are tourists, there are usually people willing to give them what they want. Some modern writers scoff at Ramona because its biggest influence was in the realm of tourism, not reform. But in California, where tourism has become a multi-billion-dollar part of the economy, they might want to think twice before dismissing its importance.

In recent years Jackson has become a scapegoat for critics who want to attack any mythical or erroneous views of early California, especially regarding the mission system (which Jackson hardly mentions in her story).15 Much of what has come to be called the Ramona Myth existed before Ramona, especially the image of the old California ranchos. Jackson was simply writing down what she heard from old Californios such as Antonio Coronel. His influence on Jackson cannot be underestimated. Meeting him for the first time, she found herself, “…transported, as if by miracle, into the life of a half-century ago … I went for but a few moments’ call. I stayed three hours and left carrying with me bewildering treasures of pictures of the olden time.”16

As Ramona-related tourism grew, claiming a piece of the pie became more and more attractive. But there was only so much local color to go around, and squabbles soon developed, not just over the settings of the story, but over the characters and incidents. The realistic feel of the novel caused many tourists to expect to find the “originals” of the various settings and characters in the story, and once again, people were found who were willing to give them what they wanted.

Brigandi expands on how exactly Rancho Camulos came to be connected with the novel:

Somewhere in all of this Ramona hoopla, someone noticed that the Moreno Rancho, where Ramona was raised, was rather like the Rancho Camulos. Not exactly, but close enough for the tourists. By 1885 Ramona-reading tourists had begun to visit there, and some unknown booster had dubbed the rancho “The Home of Ramona.” Two other factors soon helped bring Camulos into prominence—and with it, helped to spread the notion that Ramona was in some way “real.”

In April 1886, Edwards Roberts, a brother (but not a partner) of the Roberts brothers who had published Ramona, made a tour of California, writing up his impressions for the newspapers.17 In April, he visited Camulos, and announced to the public, “What I sought is this which I have found, – the Camulos ranch, the home of Ramona, whom “H.H.” created, and described as living with the Señora Moreno in this house from which I write to-night. Yes, here lived the heroine of the novel which many call the American novel, long watched for and now come at last.”

Roberts’ article, published in the San Francisco Chronicle, signaled the start of an intentional effort by the publishers, the Robert Bros., to capitalize on Rancho Camulos. Roberts’ travel accounts were later published as Santa Barbara and Around There by the Roberts Bros. in 1887.18 His original article was then added as an appendix to Ramona under the title “Ramona’s Home: A Visit to the Camulos Ranch, and to Scenes Described by H.H.” It continued to be printed in trade editions of the book for over 40 years. It further contributed to the idea that the story was not mere fiction.19

Brigandi further explains:

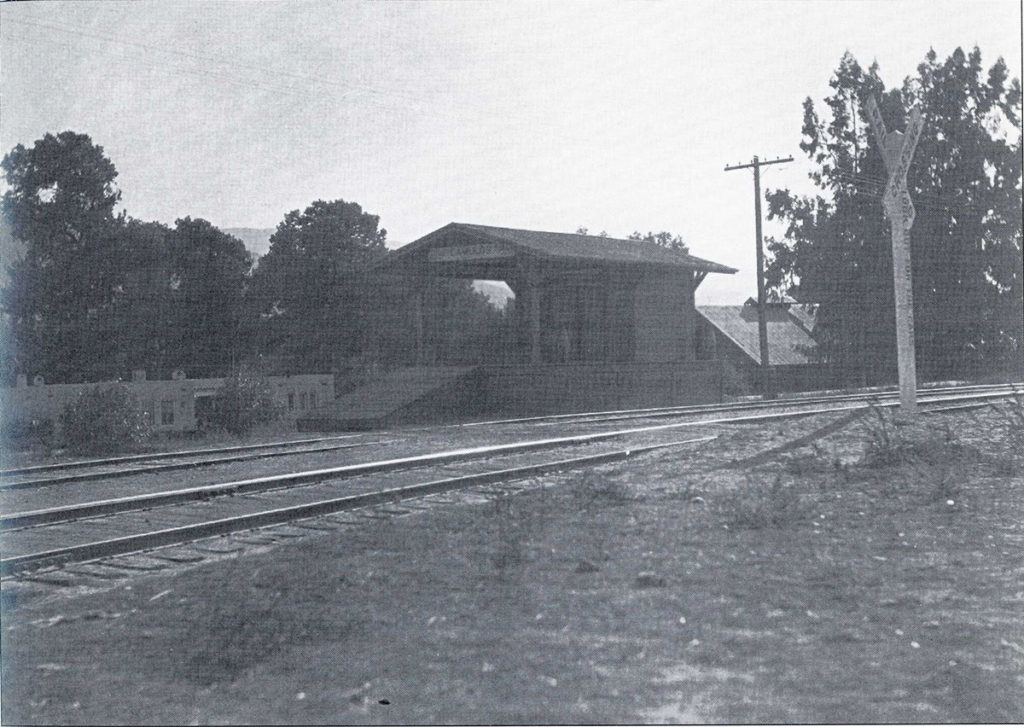

The second factor that put Camulos on the “Ramonaland” map, was the arrival of the Southern Pacific Railroad, which built its line from Los Angeles to Santa Barbara across the ranch in 1886-87 (regular service to Ventura began on May 18, 1887). Ygnacio del Valle’s son, Reginaldo, used his influence to have a small station established right on the ranch. The Southern Pacific—always looking for ways to drum up business—was quick to capitalize on the growing fame of Camulos. As they rolled into the station, the conductors would call out, “Camulos! Home of Ramona!”

Brigandi explains that Jackson’s geographical descriptions are likely intentionally vague and hint at a location that doesn’t exist. Referring to characters and locations in the novel, he writes:

…the statues at the Moreno Rancho come from Mission San Luis Rey, and Jose can ride from there to Temecula and back in one night to fetch Alessandro’s violin. It takes old Father Salvierderra six days to walk to the rancho from Santa Barbara, and Ramona and Alessandro can ride from there to San Diego in just two days; yet when a doctor is needed in an emergency, the Señora Moreno sends to San Buenaventura.

In other words—geographically speaking—there is no such place as the Moreno Rancho, and Helen Hunt Jackson never said that there was one. What she did say was that the “Indian history” (as she called it) in the second half of her story was all based on actual events; not her characters, not her settings.

Still, Camulos’ fame as the “Home of Ramona” spread. More and more tourists came, and more and more authors wrote up the place for the papers. The more the claim appeared in print, the more people accepted it. It acquired that strange authority the printed word seems to carry with so many people.

Brigandi also highlights that the Ventura County newspapers had almost nothing to say about this touristic phenomenon:

The interest seems to have been stronger outside of the county. If Camulos had been located next to a major city, with a progressive chamber of commerce, it probably would have received more local boosting. In one of the few early references in the local papers, on August 19, 1887 the Ventura Free Press noted, “We learn that a good many ‘pilgrims’ visit the Camulos to view the scene of Mrs. Helen Hunt Jackson’s Ramona. That [this] is more or less annoyance to the residents can easily be conceived. Their first inquiries often are: ‘Where is Ramona? Where is Phillipi20[sic]?’ and all the characters of the novel are minutely inquired for as though Ramona were reality and not fiction…”

Brigandi continues:

During the 1880s and 1890s, tourist excursions-organized by private companies, sometimes with the help of the Southern Pacific Railroad, often visited Camulos. Probably most of them were polite and well mannered, but those weren’t the tourists the del Valle family remembered. They had a wealth of horror stories of what they took to calling the “Boston manners” of the tourists. “For several years subsequent to the publication of ‘Ramona,’ [in] 1884,” Davis and Alderson relate, “tourist excursions to California were mainly those conducted by a Boston firm, and were composed of New England people. Camulos ranch, the home of Ramona, was one of the California places of greatest interest to them; and, by special arrangement, the Southern Pacific train stopped at the ranch for sufficient time to permit the tourists to visit the home of Ramona.

“Senator [Reginaldo] del Valle yet grows indignant when talking of the conduct of the New Englanders. They were rude, he asserts, and wholly ill-mannered. They picked the flowers and fruit, swarmed over the yard and gardens, took valuable articles as souvenirs, and invaded the dwelling uninvited; and, on one occasion, when in the room described in the novel as having been the sleeping apartment of Ramona, a woman threw herself on the bed, exclaiming, ‘Now I can say I have laid on Ramona’s bed.”21

… A decade later, another writer in the Overland noted, “… unfortunately, there were some instances not only of ignorance, but of ill-breeding. During the ‘boom,’ when land agents were advertising town lots and running excursions to this place, some of the visitors went beyond the bounds of propriety and consideration of the rights of the good people of Camulos, until at last they were refused admittance. Trophy-hunters gone mad would have carried off the bells that hung by the little chapel, had it been possible. One morning before the family had arisen, a stout, florid-faced tourist, sporting sandy side-whiskers and an air of pomposity, rushed into a private apartment, threw up the curtains and exclaimed, ‘Where is Ramony? We want to see Ramony!’22

Brigandi explains that the lack of nearby hotels, restaurants or other amenities often meant that the del Valle family provided meals and lodging for uninvited guests on multiple occasions.23 This constant stream of intrusions finally led the family to issue the following notice:

UNMANNERLY TOURISTS

The “Home of Ramona” Closed to Visitors

Because of Their Rudeness and Thievery

Our young friend, Ulpiano Del Valle is, ordinarily, one of the gentlest and most accommodating of men; but a limit is reached occasionally when he is compelled to draw the line. … Mr. Del Valle has been compelled, as a matter of self-protection, to cause the following general notice to the public to be published: “It is with regret that I am compelled by the law of self-protection to deprive pleasure seekers of seeing the home of Ramona, but patience has ceased to be a virtue. On the 12th inst., the Santa Barbara excursion train was delayed here for twenty minutes by an accident, and a mob of 300 of both sexes took advantage of the opportunity to raid the orchards as thoroughly and steal as many oranges as the time would permit, even invading the private grounds and apartments of the house. Entreaties by the one ranchman around did not avail to stop the disgraceful occurrence.

“As this is the third, and by odds, the worst invasion by such a lawless mob of marauders, of which the malicious behavior of a majority of its members would degrade professional tramps, I am obliged to state through your courtesy that while I am manager no other such band of loose excursionists will be permitted to enter within the grounds of the Camulos Rancho.

U.F. Del Valle.”24

According to Brigandi, the del Valles were not above “exploiting the Ramona Myth when it was to their advantage” and cites jokes by the family about building a “Ramona Hotel” and the use of the phrase “Home of Ramona” on the labels used to pack oranges.25 However, we would be remiss in assuming that because the del Valles had hoped to capitalize on a popular myth – one that they did not create – that they should then accept blatant disrespect and violations of their privacy. This also belies the likely tension between a Mexican family that represented a relatively privileged and landed class of people and Anglo tourists who, while fascinated with the romance of the ranchos, still likely held racist and biased views towards Mexican-Americans.

Indeed, Brigandi adds:

While Ramona gave many readers an interest in Southern California’s Indian and Hispanic past, that sympathy did not always extend to the descendants of those people. One of the del Valle girls (apparently Belle) never forgot an experience she had shortly before the turn of the century.

Being in an art-store in Los Angeles, she was shown one of these caricatures called “The Home of Ramona,” the dealer assured her that it was a “facsimile of the original” and that “a pack of greasers lived there at the present time,” without a thought that the cultured young lady before him was one of them.26

By 1910, interest in excursions to Camulos slowed, despite there still being some interest in the story. Photographers and artists had also been inspired by the novel, and the Ventura Free Press reported in 1887 that Ventura County’s own J.C. Brewster had “just returned from the Sespe and Camulos where he obtained a large number of views. Among others was a set of views illustrating the home of Ramona.”27 Brewster went on to publish a set of 13 Camulos photographs that included recreations of scenes from the novel, some of which included del Valle family members posing as characters.

Then city editor of the Los Angeles Times, Charles F. Lummis was reportedly a friend of the del Valle family and published a small book in 1888 of original photographs titled The Home of Ramona: Photographs of Camulos, the fine old Spanish Estate Described by Mrs. Helen Hunt Jackson as the Home of Ramona. The book matched descriptions of images of Camulos with quotes from the novel. The book’s cover also plays on Catholic imagery, using a rosary, and other images that evoke a sentimental view of Mexican ranch life.

The ranch also served as the setting for D.W. Griffith’s 1910 film “Ramona.” Brigandi is right to remind readers that Griffith was the director of “The Birth of a Nation.”2829 Publicity for the film emphasized cooperation with the book’s publisher and the opening title noted, “This production was taken at Camulos … the actual scenes where Mrs. Jackson placed her characters in the story.”30

Brigandi concludes that

The contemporary documentation for Helen Hunt Jackson’s knowledge of Camulos consists of exactly six words in her diary and three lines in two letters written more than a year and a half before she had even conceived of the novel she would call Ramona. Every later claim that she used Camulos as the model for the Moreno Rancho is based either on an interpretation of the novel, or on the recollections of someone who knew her.

… The continuing belief that the Rancho Camulos was “The Home of Ramona” is based as much on repetition as anything else. Like other parts of the Ramona Myth, the more times this claim has appeared in print, the more it has been accepted as true. This uncritical acceptance of the printed word is a part of the basis of the Ramona Myth that has not yet been explored. Most authors have only speculated on why the Myth spread, not how. That same acceptance of the printed word is part of what keeps the Ramona Myth alive today.

Make no mistake, we can and must talk about the Ramona Myth—it is a fascinating part of Southern California’s history—but only our history since 1884. For our earlier history we must look elsewhere.

What Brigandi’s article teaches us is the power of the written word to redefine and reframe a story. Jackson set out to write a novel that would focus attention on the oppression of Indigenous peoples and yet over 100 years later it’s still not what we remember when we discuss the novel. The tourists’ fascination with the novel did not center on the rights of Indigenous Californians or the ways in which they were and continue to be dispossessed of their land. In addition, the novel romanticized Californio life and yet led to an influx of tourists who had no reservations about disrespecting the Mexican family living in the home they seemed to feel so strongly about. Brigandi’s statement that the more “the claim appeared in print, the more people accepted it” is warning that all who read and investigate history should heed. Like always, our Journal Flashback posts are not meant to be the last word on the topics discussed and there are so many more aspects to this story than we have time here to explore. Indeed, this post has only skimmed the surface. We hope we have highlighted an aspect of Ventura County history, shared some resources, and inspired someone to do their own research and continue the discussion.

*Brigandi was an Orange County historian who took a special interest in the Ramona phenomenon. He published several books on the topic and on Southern California history, including an Images of America series book on Orange County. He also served for 12 years on the Orange County Historical Society’s Board of Directors.

- Editor’s note: The book never specifies what group of indigenous people Ramona’s mother is from. This makes clear that while well-intentioned and progressive in some senses, the novel still played on one-dimensional understandings of indigenous and non-white peoples.

- Editor’s note: While the book says that Alessandro and his band are from Temecula, it does not definitively state whether or not they are Luiseño, again highlighting how Indigenous peoples are treated like a monolith in the book.

- Editor’s note: Another common critique of the novel is how it ignores that it was Spanish and Mexican settler who first displaced Indigenous Californians and that the mission system was not benign.

- Editor’s note: This is the original author’s terminology. The museum has since changed its practices and will not use this word in current posts, materials, or articles.

- The most recent (and best) account of Helen Hunt Jackson’s efforts is Valerie Sherer Mathes’ Helen Hunt Jackson and Her Indian Reform Legacy (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1990).

- The “Ramona Myth” is really a beast with two heads. The first is the belief in the literal truth of Ramona, both the specific details (characters, settings, etc.) and in its general picture of life in Old California. The term has also been used (usually in a derogatory sense) to label any inaccurate view of early Southern California, especially concerning the Indians, the Spanish missionaries, or the Mexican rancheros. The most influential discussion of the Myth is still Carey McWilliams’ Southern California: An Island on the Land (First edition, 1946; second edition, Santa Barbara: Peregrine Smith, Inc., 1973) 70-83. McWilliams argues that the lack of reminders of earlier human history in Southern California fostered the Myth: “The newness of the land seems, in fact, to have compelled, to have demanded, the evocation of a mythology which could give people a sense of continuity in a region long characterized by rapid social dislocation” (71). The problem with this reconstruction, it seems to me, is that every part of the United States – even those with very visible pasts such as New England – has its own romantic regional myths, often fueled by fiction. For an interesting response to Mc Williams, see Franklin Walker’s A Literary History of Southern California (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1950) 123-132. Walker decries McWilliams’ “wholehearted condemnation” of Jackson, and adds, “In writing Ramona she was not motivated by a desire to create a romantic past or to make money but to point out what she considered to be a disgraceful injustice.” He blames the Myth on “the extraordinarily persistent, tendentious, and to certain degree nauseating activities of the Ramona antiquarians …. “ The most recent study of the Myth (soon to be published by the University of California Press) is Dydia DeLyser, “Ramona Memories-Constructing the Landscape in Southern California Through a Fictional Text” (unpublished master’s thesis, Syracuse University, 1996).

- For the general history of Camulos, I rely on Wallace E. Smith, This Land Was Ours: The Del Valles and Camulos (Ventura: Ventura County Historical Society, 1977).

- Jackson herself seems to have suspected that he former los Angeles mayor and California State Treasurer was playing the part. In “Echoes in the City of Angels” she notes that he would sometimes correct his wife’s translations, “… for he well understands the tongue he cannot or will not use for himself.”

- This claim first appears in print in C.F. Lummis’ fifth 1888 booklet, The Home of Ramona. In 1913 Mariana Coronel is quoted as saying Jackson “would gladly have located the scene of ‘Ramona’ at our hacienda, and doubtless would have done so but for the suggestion made by Don Antonio himself, and insisted upon by him, that Camulos was the more fitting place.” C.C. Davis and W.A. Alderson, The True Story of “Ramona” (New York: Dodge Publishing, 1914), 192.

- Quoted in Davis and Alderson, The True Story of “Ramona” (1914), 179. In a letter to Abbot Kinney five days later she added, “Mrs. Del Valle away from home, unluckily, so I staid [sic] only the morning at the ranch: but it was a most interesting place, and the daughters, cousins, sons and sons, sons and daughters all as Mexican and un-American as heart could wish.” Quoted in Smith (1977) 177.

- Most of this research was distilled into her book, A Century of Dishonor (Boston: Roberts Bros., 1881), which was most recently reprinted by the University of Oklahoma Press (1995) with a new introduction by Valerie Sherer

- Jackson made eleven specific recommendations, including the proper survey and marking of all reservations and the removal of white settlers, the appointment of a special attorney to represent the Indians, and the distribution of farm implements to the reservations. Her report was later included as an appendix to A Century of Dishonor.

- Jackson to Coronels, November 8, 1883. Quoted in Walter Lindley and J.P. Widney, California of the South (New York: D. Appleton & Co., 1888), 201-202.

- This chronology is important to bear in mind because of the many claims and counter-claims about the genesis of the story. There were any number of people who later stated that Jackson had discussed Ramona with them while she was in Southern California, or had written all or part of it in their homes.

- It is ironic, I think, that a book that was so far ahead of its time-not just in its portrayal of the Indians, but of its Mexican and female characters as well-is now attacked for not meeting some arbitrary modern standard of “political correctness.” If we can see further today, it is only because we stand on the shoulders of people like Helen Hunt Jackson. To ignore their contributions from the past also condemns to oblivion our own contributions at some future date when styles have again changed. I might add that I sometimes wonder how many of these critics (it’s interesting how many of them are artists, and not historians) have actually read Ramona. Recent artistic attacks on the Ramona Myth include the stage play L.A. Real and the “video installation” entitled Ramona’s Bedroom (Los Angeles Times, April 22, 1993).

- “Echoes in the City of Angels,” Century magazine, December 1883. Coronel’s recollections, dictated for Hubert Howe Bancroft in 1877, have only recently been published as Tales of Mexican California (Santa Barbara: Bellerophon Books, 1994).

- Raymond Kilgour, Messrs. Roberts Brothers, Publishers, Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1952), 230. Roberts Bros. was founded by Lewis and Austin Roberts in 1861, and bought out by Little, Brovvn & Co. in 1898.

- Phil Brigandi, “The Rancho and the Romance,” The Ventura County Historical Society Quarterly, Volumes 42, Numbers 3 & 4 (1998), 15.

- Brigandi, 16.

- Editor’s note: For clarity, the author has used this phonetic spelling of the way Anglo visitors would likely have pronounced the name Felipe, the son of the Moreno family in the novel.

- Davis and Alderson, The True Story of “Ramona” (1914), 106-107.

- Eleanor F. Wiseman, “Hacienda de Ramona,” Overland Monthly, February 1899.

- Brigandi, 20.

- Ventura Weekly Democrat, February 28, 1896.

- Brigandi, 22-23.

- Wiseman, “Hacienda de Ramona,” Overland Monthly, February 1899.

- Brigandi, 27.

- Brigandi, 30.

- Editor’s note: “Birth of a Nation” was a 1915 silent film often remembered for its racist portrayal of the Ku Klux Klan as heroes who restored order to the South and African-Americans as unintelligent and sexually aggressive. It is interesting to note that Griffith would go on to direct this film after Ramona. It might be stating the obvious, but for clarity’s sake the cast of Ramona was all white, despite being a novel about mostly non-white people.

- Brigandi, 30.