By Library Volunteer Andy Ludlum

It was January 15, 1945, a chilly Monday evening near the end of World War II. Saticoy farmer Jack Tobias and his family were eating dinner when they heard an explosion. Jack dropped his fork and raced to join his neighbors at the fire station. Word quickly spread through the group that the explosion had been an enemy bomb. Forty years later, Tobias described Saticoy the next morning as “a rat’s nest.” He told the Ventura County Star Free Press that the “FBI was there and some military units, they even ran a few tanks into town.”

The explosion had occurred in the sandy Santa Clara riverbed about three-quarters of a mile west of the Saticoy bridge and about 200 yards north of Vineyard Avenue. The site was sealed off, but Tobias managed to slip in and get a look. He saw “a hell of a big hole.” There was a crater in the sand between 10 and 12 feet deep and 15 to 20 feet in diameter. There were no injuries and, other than the big hole, no damage. But due to wartime censorship, there was no mention of the explosion in the local newspapers. What most residents of the farming community would not know for another eight months was that the explosion was caused by a bomb carried by a paper balloon launched from a Japanese beach three days earlier.

Japanese School Girls Assembled the Paper Balloons

Five months before the Saticoy bombing, an army officer from the military arsenal in Kokura, Japan came to 15-year-old Tanaka Tetsuko’s school. Tetsuko and about 150 members of the senior class of the Yamaguchi Girls’ High School were conscripted by the military to work on what she was told was a “secret weapon” that would “fly to America.” No one said exactly what they were making, only that it would have a great impact on the war.

The girls wore headbands designating themselves as members of the Student Special Attack Force. Like all soldiers in the Imperial Army, the girls recited the official military code of ethics, promising absolute loyalty to the Emperor, before they began work each morning. They worked exhausting 12-hour shifts gluing together reams of washi paper, made from the inner bark of the mulberry tree. They used a paste made of a potato-like vegetable called konnyaku. The plant was considered so valuable it was designated by the Imperial Army as war material. Tetsuko was proud to serve her country, covering the sheets of paper with a thin layer of paste, letting them dry, then applying a thicker layer of paste with a sightly bluish tint, “like the color of the sky.”

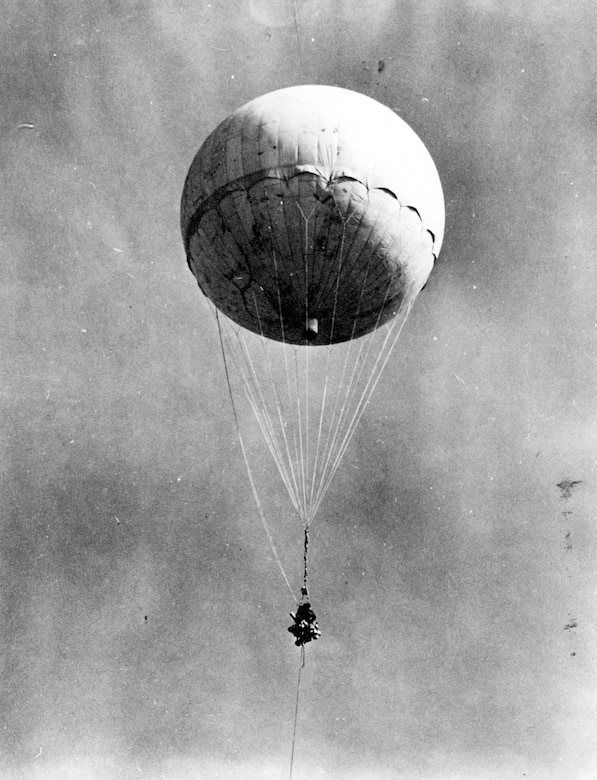

Dozens of these seemingly crude paper sheets were joined to make balloons strong enough to keep hydrogen gas from escaping, even at high altitude. Each balloon measured over 30 feet in diameter and was inflated with 19,000 cubic feet of hydrogen. The balloons could lift 1,000 pounds and carried five bombs, usually a 33-pound high-explosive bomb or a 26-pound incendiary, along with four 11-pound incendiaries. The balloons were known to the Imperial Army by their code name “Fu-Go”, short for fusen bakudan which means “fire balloons” in Japanese.

Little Known Research Reveals the Secrets of the Jet Stream

In the 1920s a Japanese meteorologist named Wasaburo Oishi discovered the high-altitude currents now known as the jet stream. His work was not widely shared in the scientific community and remained in obscurity until the Japanese military realized Oishi’s air currents could be used to carry bombs across the Pacific.

But why would the powerful Japanese Army resort to using paper balloons as a weapon? When American aircraft led by Lieutenant Colonel James Doolittle bombed Tokyo in 1942, it was a shock to the Japanese military to learn they were vulnerable to American air attacks. Japan did not have a long-range bomber like the B-29, and they did not have enough aircraft carriers to move the few aircraft they had across the Pacific. An army research institute specializing in covert tools and special weapons was tasked with finding a way to bomb America. They settled on the idea of the Fu-Go. The original plan was to release the balloons from submarines off the west coast of America. That had to be scrapped when all submarines were needed for the Guadalcanal campaign between August 1942 and February 1943. The idea of a balloon bomb floating 6,200 miles on a jet stream conveyor belt was an ingenious response to a lack of resources. In the winters of 1943 and 1944 meteorologists tested transpacific balloons on the jet stream and concluded it would take an average of 60 hours to reach America.

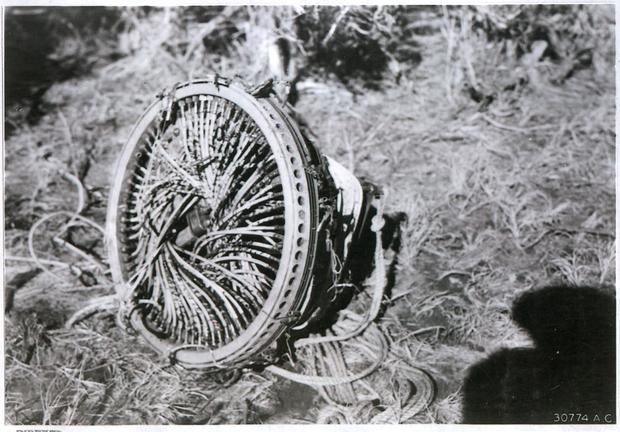

Suspended from the balloon was a chandelier-type ring holding the bombs, the ballast, and a device to regulate the balloon’s altitude. This timing device was connected to sandbags hanging from the chandelier ring. After launch, the balloon rose into the jet stream at about 30,000 feet and began its three-day journey across the Pacific. At night, the hydrogen gas in the balloon would shrink as the air cooled. This would make the balloon lose altitude. If not corrected it would crash into the sea. After a set number of hours, the timing device would trigger a small charge that dropped several of the sandbags into the sea. The lightened balloon would climb back up into the jet stream. It would travel in this up and down pattern across the ocean. After the balloon reached its destination and dropped its bombs, a demolition block containing a picric acid explosive would destroy the control mechanism and most of the chandelier ring to prevent reverse engineering by the Americans.

Jellyfish in the Sky Are Launched

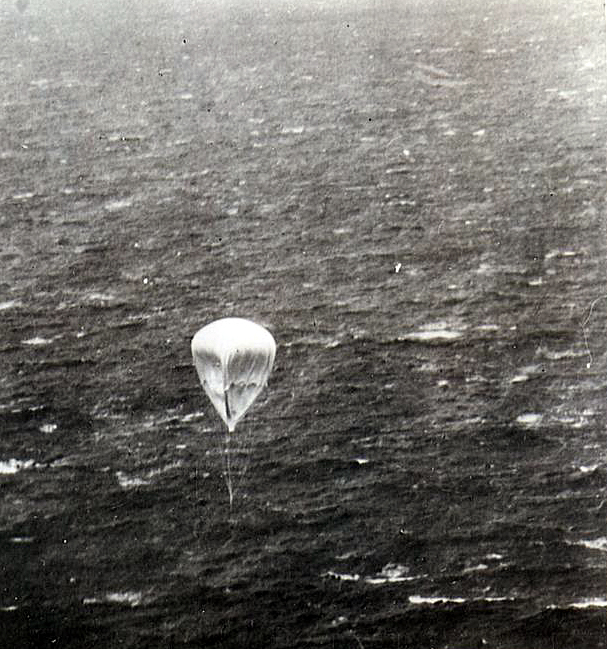

The first balloons were launched on November 3, 1944. The jet steam was strongest between November and March and there were only about 50 days with the right wind conditions. It took 30 men over half an hour to get one balloon ready for flight. When launched in groups, the balloons were said to look like jellyfish in the sky. The Japanese hoped the balloons would land at random sites destroying buildings, starting forest fires, and, most importantly, terrorizing Americans.

On November 5, 1944, a balloon was found 50 miles south of Reno, Nevada. By the time military experts got a look at it there was nothing left but a few scraps. In November and December, balloons were found in Montana, Wyoming, and Oregon. The Montana balloon was first misidentified as a parachute. On December 18, the FBI issued an official announcement saying it was part of a balloon that had an incendiary device and detonator attached. While the balloons were not front-page news, they were not yet kept secret. The official government response to what was falling from the sky was to admit uncertainty.

News Reports of the First Balloon Bombs Are Suppressed

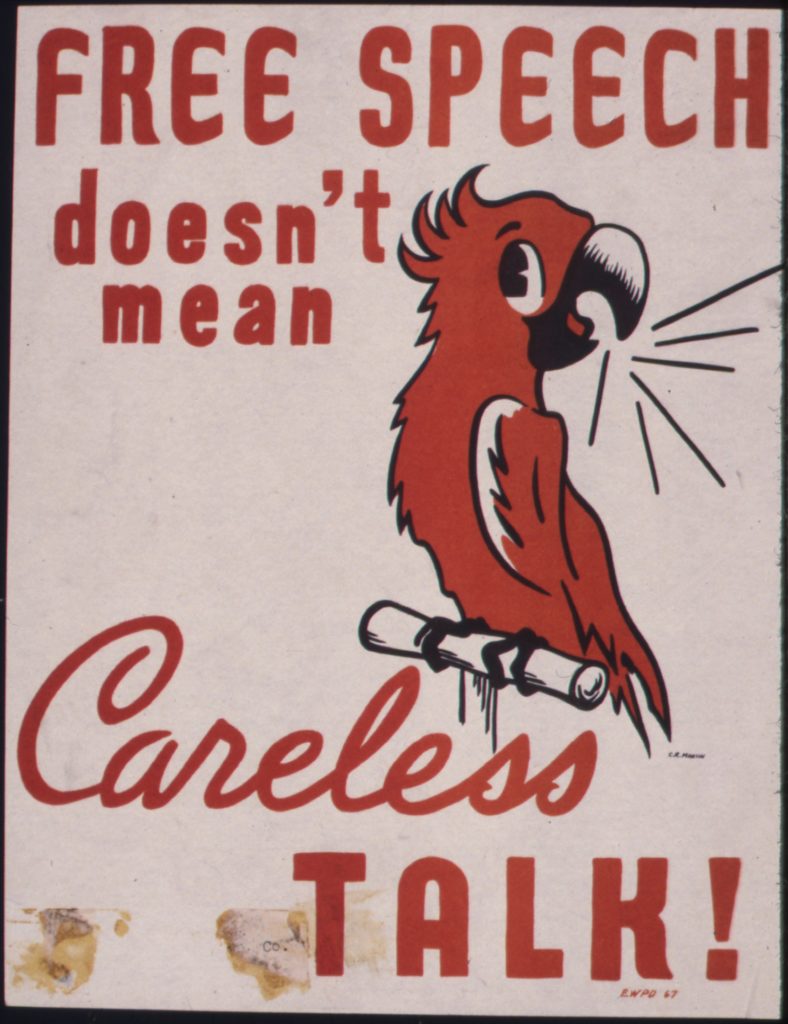

On January 1, 1945, the Associated Press ran a short, three-paragraph story about a balloon found near Estacada, Oregon adding that it was like the one found in Montana. This time the FBI refused to comment. The Portland Oregonian ran a front-page story complete with a picture of soldiers hunting through the woods for more balloon parts. The military was not pleased. While the only formal censorship imposed on the press during the war was on overseas reporting, the government and the military exercised substantial informal control over what news Americans could read or hear by appealing to journalists’ patriotism. The public and the media had been conditioned by War Office informational posters like “Free Speech Doesn’t Mean Careless Talk.” News editors were told any balloons approaching the United States from the Pacific could be enemy attacks. Reporting about the balloons would aid the enemy. Reporters and editors censored themselves even as the public continued to discover more balloon scraps.

In January following the Estacada incident, fragments of more Japanese balloon bombs were found. There were two in Alaska, two near Medford, Oregon, and one in the Canadian province of Saskatchewan in addition to the one that exploded in Saticoy.

At first, no one believed that the balloon bombs had come from Japan. Colonel Sigmund Poole, head of the U.S. Geological Survey’s military geology unit was given sand from one of the balloon’s ballast sandbags after he reportedly asked, “Where’d the damn sand come from?” The sand was unique, and Poole’s team of geologists concluded that it came from a beach on the island of Honshu east of Tokyo. Aerial reconnaissance soon discovered two hydrogen production plants nearby, which immediately became the targets of American bombers.

The U.S. military was concerned about the incendiary bombs carried by the balloons. The winter was dry and destructive forest fires could spread quickly. Firefighters were stationed along Pacific coastal forests. Pilots tried to shoot down incoming balloons. But they were traveling at high speed at 30,000 feet and only 20 were hit. Ultimately, the military concluded the most serious threat posed by the balloon attacks was panicking the American public. Through the first months of 1945, the U.S Office of Censorship continued to request that newspaper editors and radio broadcasters not discuss the balloons.

Meanwhile, Japanese authorities were telling their people at home that the bombs were hitting targets. It was a lie intended to boost morale. After the war, Japanese officers told the Associated Press the balloon program was stopped for several reasons. They were running out of kozo, the mulberry tree bark used for the paper production, B-29s had destroyed their two key hydrogen plants, and they had no evidence the balloon attacks were working. The censorship was so effective that the officers said “they finally decided the weapon was worthless and the whole experiment useless because they had repeatedly listened to [radio broadcasts] and had heard no further mention of the balloons.” Ironically, the last balloons were launched shortly before a fateful church picnic in Oregon on May 5, 1945.

Everything Changed After a May Tragedy

It was a beautiful spring day in the quiet logging town of Bly in southern Oregon. Young Reverend Archie Mitchell had just accepted a new post as pastor of the Christian and Missionary Alliance Church. His 26-year-old wife Elsie was five months pregnant with their first child. The Mitchells had invited five children from their Sunday school class, all between the ages of 11 and 14, to join them for a picnic and fishing trip at Leonard Creek, near Gearhart Mountain, eight miles northeast of Bly.

After heading up a one-lane gravel road, Mitchell parked his sedan near the ponderosa pines and began to unload picnic baskets and fishing rods. Elsie and the children went off to explore the forest leading to the creek. When one of the girls stumbled across a strange white canvas on the ground, she called to the rest of the group. “Look what we found,” Elsie called to her husband back at the car. “It looks like some kind of balloon.” Mitchell saw the group gathered in a tight circle around the object. As one of the children reached down to touch it there was a huge explosion. In an instant, Elsie, her unborn child, Sherman Shoemaker, Edward Engen, Jay Gifford, and Joan and Dick Patzke were dead. They were the only people killed by an enemy attack on American soil in World War II.

The tragedy in Bly was too big to keep secret, a funeral for four of the young victims was attended by 450 people. Yet at first, the military tried to downplay the explosion. An intelligence officer from Fort Lewis in Washington secured the site and told reporters to identify the explosion as being of “unknown origin.”

The term “unknown origin” triggered the very panic news censorship was intended to prevent. Newspapers received dozens of calls from scared readers. Bizarre rumors began to spread, such as the U.S. was being bombed by robots, that parts of San Francisco had been wiped out by secret bombs, and that the balloons were carrying deadly poison gas.

On May 22, the press got a joint communique from army and navy intelligence about the balloon bombs. The contradictory statement acknowledged the existence of the balloon bombs, but insisted the attacks were so scattered and ineffective that the chances of a particular spot being hit were just “one in many millions.” A United Press story in the Santa Paula Chronicle quotes the war department as saying the bombs had caused no “property damage” and had not succeeded in “their apparent purpose of starting forest fires.” Nine days later the Office of Censorship realized it was impossible to hide the link between the balloon bombs and deaths in Bly and finally okayed publication of the story.

The Public is Finally Warned About the Balloon Bombs

Although it was a month too late for the Bly victims, the military’s public information policy had changed. Instead of a press blackout, authorities began to warn Americans about the dangers of the balloon bombs. Army intelligence released a short statement intended to be read to all school children living west of the Mississippi. The Moorpark Enterprise on May 24, 1945 described how students at Simi Valley Elementary School were told that the greenish-blue paper balloons were dangerous and should not be approached or touched. The newspaper also revealed a member of military intelligence had asked the newspaper in January not to report any news of the balloon bombs.

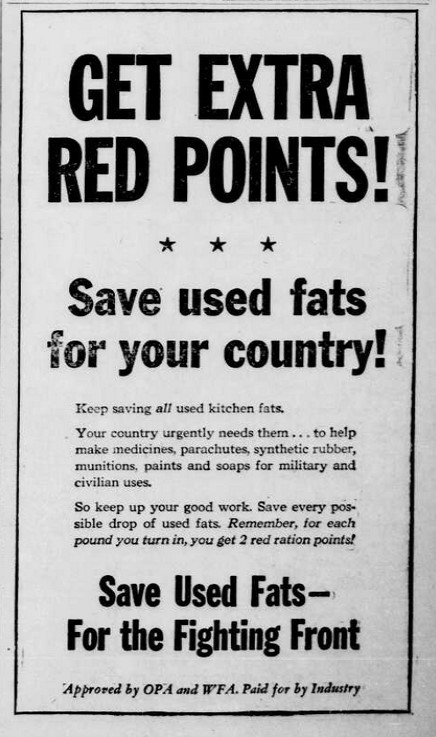

It was not controversial for most Ventura County residents to learn they had been the target of an attack eight months after the fact. The voluntary censorship of newspapers and radio broadcasts had become a culture respected by editors and reporters. The American public was used to sacrifice. Gasoline, meat, and clothing were tightly rationed. Ventura County residents were even asked to exchange used cooking fats for ration points.

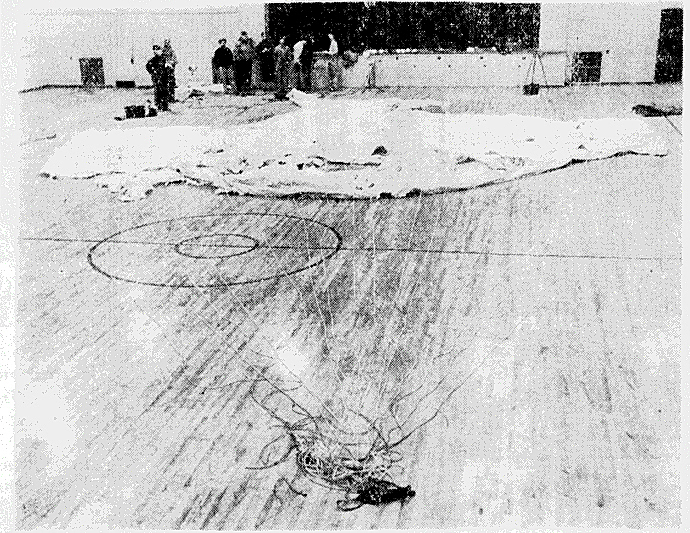

Ventura County readers did not learn about the January balloon incidents until August 21. A front-page story in the Oxnard Press Courier revealed two Japanese balloons had landed in Ventura County. One had exploded, causing the crater in Saticoy. Another, on January 20, had apparently dropped its bombs in the ocean and the balloon had landed in flames near the Mira Loma airport west of Oxnard, leaving only ashes. The article also revealed the balloon from the Saticoy explosion had drifted to the southeast for another 15 minutes before landing on the David L. Strathearn ranch three miles northeast of Moorpark. It was found, two days later, lying in the grass on the side of a hill in an area known as Happy Camp canyon. The article includes a picture of the “aquamarine blue and dusty cream” camouflaged balloon spread out on the gymnasium floor at the Port Hueneme Naval Base.

They were also willing to surrender their First Amendment rights provided it prevented the leak of vital information that could aid the enemy. In November 1946, the Oxnard Press Courier defended not revealing that balloon bombs had fallen in the county, saying “that would have furnished information to Japan and would have encouraged them to send over more balloons in their rather aimless hope of knocking out the Navy harbors and the aircraft plants near here.” Another incident kept from the public happened in March 1945 when a balloon bomb hit a high-tension power line and caused a temporary blackout at a top-secret plant in Hanford, Washington. It was producing the plutonium that would be used in the atomic bomb dropped on Nagasaki five months later.

The Danger Remains Today

Over a five-month period ending in April 1945, the Japanese launched 9,000 fire balloons. The Japanese predicted, perhaps optimistically, that about 900 would make the trip across the Pacific. About 300 were known to have reached North America, from Alaska to Mexico and as far inland as Michigan. Except for Bly, most fell in remote, uninhabited areas and caused no deaths and little damage. But, to this day, experts believe not all the balloons have been found. Hikers and hunters in the Pacific Northwest are advised to be alert and careful. In 2014, two forestry workers in Lumby, British Columbia stumbled across a balloon bomb that had been in the dirt for almost 70 years. The Royal Canadian Mounted Police decided it was too dangerous to move. They packed C-4 on either side of the bomb and “blew it to smithereens.”

As a middle-aged woman, Tanaka Tetsuko, the Japanese teenager who had been so proud to paste together balloons as a member of the Student Special Attack Force looked back on her wartime work with shame. She said, “We only learned some forty years later that the balloon bombs we made had actually reached America. They inflicted some casualties, among them five children and a woman on a picnic in Oregon. When I heard that, I was stunned. I made those weapons. Some of us got together and felt we would like to organize an effort to apologize. I started with my classmates but encountered strong resistance.”

Make History!

Support The Museum of Ventura County!

Membership

Join the Museum and you, your family, and guests will enjoy all the special benefits that make being a member of the Museum of Ventura County so worthwhile.

Support

Your donation will help support our online initiatives, keep exhibitions open and evolving, protect collections, and support education programs.

Bibliography

- “Balloons That Bombed : 49 Years Ago, Japanese Explosives Drifted Into the Footnotes of Ventura County History.” Los Angeles Times. Last modified January 16, 1994. https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1994-01-16-mn-12517-story.html.

- “Beware Of Japanese Balloon Bombs.” NPR.org. Last modified January 20, 2015. https://www.npr.org/sections/npr-history-dept/2015/01/20/375820191/beware-of-japanese-balloon-bombs.

- Hornyak, Tim. “Winds of War: Japan’s Balloon Bombs Took the Pacific Battle to American Soil.” The Japan Times. Last modified July 25, 2015. https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2015/07/25/national/history/winds-war-japans-balloon-bombs-took-pacific-battle-american-soil/.

- “An Ill Wind: How American Secrecy Stopped a Japanese Terror Attack.” HistoryNet. Accessed November 19, 2020. https://www.historynet.com/an-ill-wind-japanese-terror-attack.htm.

- “In 1945, a Japanese Balloon Bomb Killed Six Americans, Five of Them Children, in Oregon.” Smithsonian Magazine. Last modified May 22, 2019. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/1945-japanese-balloon-bomb-killed-six-americansfive-them-children-oregon-180972259/.

- “Japanese Balloon Bombs “Fu-Go”.” Atomic Heritage Foundation. Accessed November 19, 2020. https://www.atomicheritage.org/history/japanese-balloon-bombs-fu-go.

- “The Japanese Balloon Bombs of World War 2.” Amusing Planet – Exploring Curiosities. Last modified May 28, 2018. https://www.amusingplanet.com/2018/05/the-japanese-balloon-bombs-of-world-war.html.

- “Japan’s Secret WWII Weapon: Balloon Bombs.” National Geographic. Last modified May 27, 2013. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/news/2013/5/130527-map-video-balloon-bomb-wwii-japanese-air-current-jet-stream/.

- “Killer Balloons Over America – America in WWII Magazine.” America in WWII Magazine: The War. The Home Front. The People. Accessed November 19, 2020. https://www.americainwwii.com/articles/killer-balloons-over-america/.

- Klein, Christopher. “Attack of Japan’s Killer WWII Balloons, 70 Years Ago.” HISTORY. Last modified May 5, 2015. https://www.history.com/news/attack-of-japans-killer-wwii-balloons-70-years-ago.

- Moorpark Enterprise. “Valley School Children Cautioned on Japanese Paper Balloons.” May 24, 1945.

- Oxnard Press Courier. “9,000 Bombs Sent up in Jap Balloons.” January 16, 1946.

- Oxnard Press Courier. “Balloon Bomb Attacks Fewer at War’s End.” August 16, 1945.

- Oxnard Press Courier. “Balloon-Bomb Not Effective.” May 23, 1945.

- Oxnard Press Courier. “County Gets Two Jap Balloons.” August 17, 1945.

- Oxnard Press Courier. “Jap Bomb Explosion Near Saticoy Revealed By Navy.” August 21, 1945.

- Oxnard Press Courier. “The Hand of the Censor.” November 30, 1946.

- Santa Paula Chronicle. “Balloon-Borne Bombs of Japs Attack U.S.” May 22, 1945.

- Santa Paula Chronicle. “Explosion of Nip Balloon Bomb at Saticoy Cited.” August 16, 1945.

- Ventura County Star Free Press. “The day they bombed Saticoy.” August 12, 1985.