By Library Volunteer Andy Ludlum

It was a stand-off worthy of the old Wild West. The taciturn lawman was face to face with a huffing, puffing adversary. Neither was ready to back down.

It was 1903 and the lawman, Ventura County Undersheriff William Reilly, was leading 600 skittish pigs from his Conejo ranch to market in Los Angeles. Reilly referred to his pigs as “broncos.” They had spent their lives feeding freely and weren’t used to people and the noises of modern life. Reilly was especially worried about getting his “fat porkers” over the narrow Calabasas Grade. Should anything spook the pigs, a year’s profits would disappear in the dense brush that grew along the road. Reilly was whistling and cooing to his unruly herd from a horse and buggy while scattering a little wheat to keep the pigs on the road. He was part way up the grade when it suddenly appeared at the top – an automobile – with its horn tooting and its gasoline engine ringing, clanging, huffing, and puffing. Reilly noticed the pigs were getting hard to handle. He hurried up to the auto driver. “Stop that machine!” he shouted, “You will stampede my hogs!” “To hell with your _____ old hogs,” shouted back the driver. “Git out of my way! I’m going through!” The puffing machine continued to approach the pigs, which were grunting restlessly. A crisis had come. Reilly whipped out a long-barreled revolver from somewhere in his overalls and pointed it at the man in the automobile and said, slowly and very deliberately, “Now you stop that machine quick, or I’ll stop it for you.” The disgusted driver complied, and he and Reilly stared at each other as the 600 pigs passed by, grunting along the dusty road past the silent machine. The pigs made it to market and brought a nice price per pound.

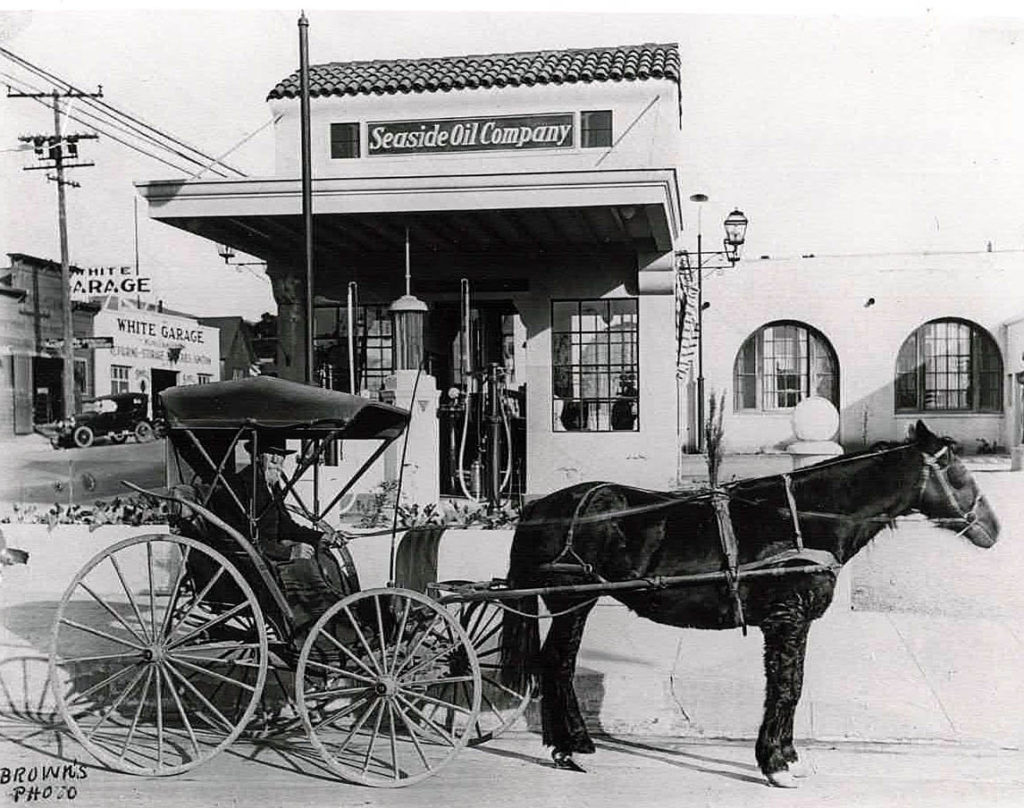

The standoff on the grade happened early in a 15-year period when Ventura County began the sometimes-awkward transition from horses to automobiles.

Noisy and Unreliable Playthings of the Rich

Inventors began tinkering with “horseless carriages” in the 1860s. Built on carriage or wagon chassis, most were noisy and unreliable and could be steam, electric, or gasoline powered. The Ventura Free Press reported in October 1895 that horseless carriages had begun appearing in big U.S. cities. The paper concluded that the high cost of the vehicles “will prevent their coming into common use for some time yet.” But they predicted the horseless carriages would “supersede many methods of locomotion now in use,” and rather darkly suggested the only demand for horses would come from “horse meat canning companies.”

In December of 1896, Dr. O. V. Sessions, Hueneme’s only doctor, received an engine for a horseless carriage from New York. Two weeks later the Free Press reported that he was testing the battery on his “motor wagon” but wouldn’t have it running until the summer. No other mentions of Sessions’ project were made and there were no indications it was ever successful.

Horseless carriages became commonly known as automobiles by the end of the 1890s. Their arrival, even in big towns, attracted considerable attention. The Free Press reported that Los Angeles reporters followed a two-seat automobile through town, even naming it “the Stomachless Steed.”

One early Saturday morning in August 1900, Ventura residents were surprised by “the appearance of an automobile gliding along Main Street noiselessly save for the warning clang of the bell.” Mr. and Mrs. H. C. Turner were on the way from their Los Angeles home to San Francisco, driving the 450 miles in six days.

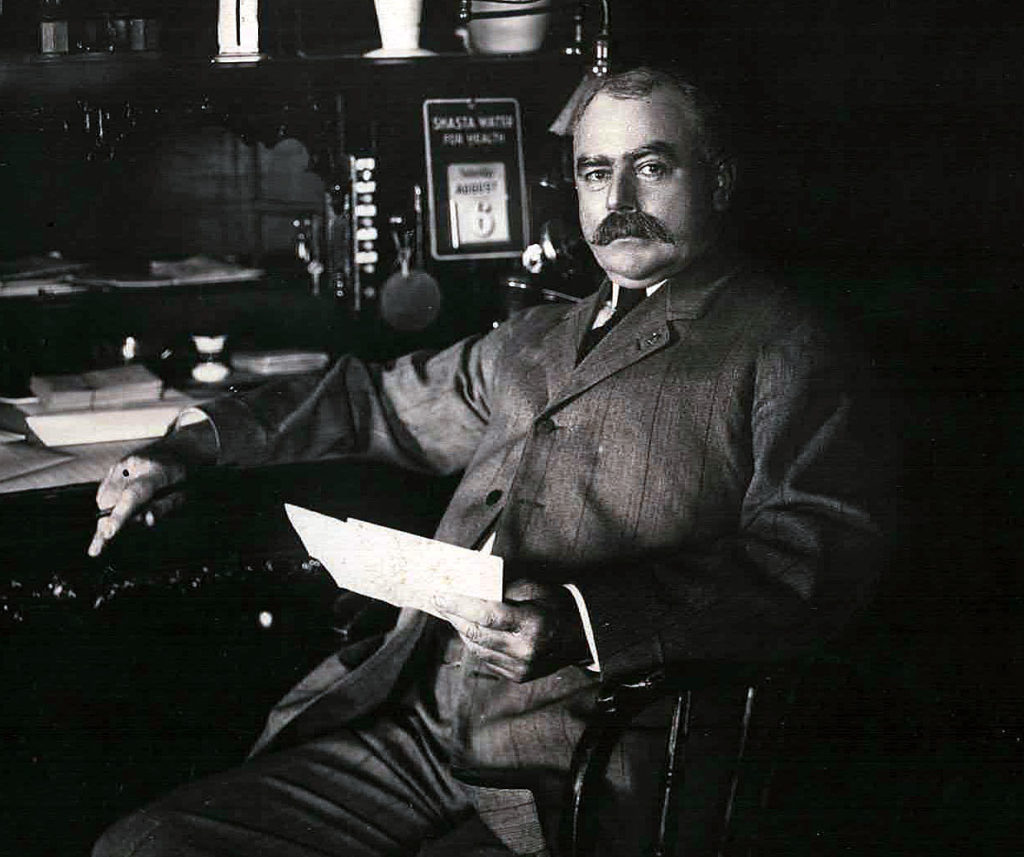

Ed Sheridan in his book History of Santa Barbara, San Luis Obispo and Ventura Counties, lists A.C. Stewart of Santa Paula as being the first automobile owner in Ventura County in 1902. Stewart received a patent for an automobile design in 1899 and opened the Fidelity Machine Shops in Santa Paula. Shortly after Stewart, Dr. J. H. Sloan of Santa Paula bought an automobile. The first vehicle owned in the City of Ventura was brought in by H. A. Giddings in February 1903.

Stewart’s car received regular attention from the Free Press which noted how he is “often seen taking a ride in the new automobile of his manufacture.” Stewart and his wife “attracted much attention and favorable comment” when they drove in the 1901 Santa Paula Fourth of July parade. The couple would regularly entertain their friends by giving them a spin about Ventura.

Stewart even duplicated a local courtship ritual in 1902 when he traveled the “Golden Triangle” by automobile. The triangle was formed by the rugged, unpaved roads connecting Ventura, Ojai, and Santa Paula. Young lovers would announce to family their intentions to “ride the triangle,” which was an unchaperoned, all-day ordeal. The young man would provide a horse and buggy, the young woman would pack food for the trip. Parts of the road were so steep they’d have to get out of the buggy and push, all the time being wary of bears and snakes. It was said if they were still speaking to each other by the end of the long day, they would soon marry.

Stewart began selling automobiles. He advertised a gasoline-powered Oldsmobile in the Free Press, noting it was simple to operate and “economical,” running 30 miles on just a gallon of gasoline. His use of the word “economical” might have been a stretch. The price of the Oldsmobile was $800 ($28,220 in 2022 dollars). According to the 1900 Census, the average annual salary in the United States was about $450.

To promote car sales, the Stewarts regularly shared their driving adventures with the Free Press. The couple and their friends made a round-trip journey to Los Angeles, noting the return trip took only seven hours. Mrs. Stewart and her friend Mrs. L.B. Hogue were often seen driving in Ventura. The newspaper noted, “Mrs. Stewart has become an excellent chaffeuress and takes frequent trips around the county.” In the early 1900s, even a brief appearance of an automobile was a community event. The Free Press reported that Piru was “full of excitement for about two minutes” when an automobile quickly passed through town. “All that was seen was a little streak of dust away off toward the city by the sea. (Ventura).” A car stopping for water and gasoline in Moorpark made the news as did “Oxnard’s automobile,” owned by a young man which was seen “spinning around town at high speeds.” On his first trips through the town, crowds of boys followed him on foot or on bicycles.

Public Fascination Turns to Trouble

Despite the public fascination with automobiles, there were signs that motorized vehicles and horse and buggies wouldn’t coexist without trouble. The Free Press described how an Ojai judge barely escaped injury when his horse was spooked by a motorcycle and ran into a fence, splitting a post in two. Interestingly, in the same column, eight paragraphs above, the newspaper noted that “M. H. Cook has just received his motorcycle and is spinning around town.”

A Santa Paula man, Hogan Herd, broke his collar bone when he was thrown out of a buggy when his horse became frightened by a passing automobile. An automobile owned by citrus rancher Charles Collins Teague, founder of the Limoneira Company, spooked a horse pulling the Santa Paula milk wagon. The terrified horse dashed up the street, eventually overturning the wagon and spilling the milk cans into the road. No one was hurt, “but several local customers had to drink their coffee without cream.”

In 1903 conflicts were still infrequent as the county had only a handful of automobiles. Santa Paula had the most, seven. In July the Free Press suggested, “the automobilists epidemic is getting alarming. Two more prominent citizens are down with acute attacks and others are showing strong symptoms of the disease.” A tongue-in-cheek editorial proclaimed, an “eminent authority says a new ward will have to be added to asylums for those afflicted with motor-mania.”

The newspapers were becoming increasingly critical of drivers’ behavior. The Free Press stated, “Automobiles are numerous about the streets of Oxnard, or rather one automobile makes itself numerous as it is seen flying about several times a day.” Piru residents were up in arms about the “gross carelessness” of drivers racing through town. They complained about narrow escapes from serious accidents caused by the “red devils” driving at high speed. “Red devils” was a common name for these early cars, as red was the most popular color of the day.

The newspaper took some delight in highlighting the unreliability of the early machines, sharing a “rumor” that an auto had lost its brakes, forcing a Santa Paula man to drive up a long canyon road until his “go-devil” ran out of gas. The Oxnard Courier offered its editorial support for a father with its unsympathetic comment that 19-year-old “Miss Alice Roosevelt is said to have wept because her papa wouldn’t let her have an auto.”

New Motorists Had to Pass Though Ventura County

Motorists traveling north from Los Angeles to Santa Barbara or San Francisco passed through Ventura County. Henry Chisholm attempted to set a time record from Pasadena to Santa Barbara. He was making good time in a speedy, “red racer” until he reached Ventura. Instead of taking the Casitas Pass Road, he attempted to go along the beach. The water at the Ventura River crossing was too deep and the “gasoline fire in the machine was extinguished in the stream.” The car was towed to the other bank and the machine was started again. But it was slow-going in the heavy sand and after about eight miles he gave up. Chisholm flagged down the passing southbound train and returned to Ventura. A local man returned with his wagon the next morning and rescued the car just as “the breakers were playing about it.”

In the heyday of El Camino Real, the natural trail along the beach was considered the main route between the Ventura and Santa Barbara missions. Casitas was a steep mountain pass and was too long and out of the way to be favored as the highway of choice. Even when the railroad eventually connected the two cities, there was always a desire to develop a shorter, more direct route to Santa Barbara along the coast. But travelers on foot or horseback had to wait for low tide to make their way along the sandy beaches and around the coastal bluffs

Even though Casitas Pass had been widened into a stagecoach road, the arrival of the automobile brought increasing conflicts. J. W. Taylor wrote the Free Press saying those “who are not able to own an automobile” are forced to travel over the pass “in great fear and mental depression” due to young men driving autos at “reckless, break-neck speed.” He singled out one man who demanded wagon drivers “give him the right of way or he will take a wheel off of them.” Taylor claimed three men in an automobile nearly drove him and his family off a 100-foot bank. He pleaded for protection from such “will-be” murderers. Short of that, he suggested acting on his own, saying “We have guns and maybe we will turn them into rear tire perforators of the horseless carriage.”

The Ventura newspaper editors were outraged in 1903 when the Los Angeles Herald reported that Ventura County roads were bad and unfit for automobiles. The Herald quoted a motorist named Jeness who said, “in the future when he wanted to get to Santa Barbara, he would ship his auto by rail.” The Free Press replied, “We can only weep. If Jeness will just let us know when he passes through by rail, we will see that the clocks are all stopped and the bells tolled and the houses draped in mourning, for it will be a solemn occasion.” County Supervisor Thomas Gabbert told the paper the county had 50 miles of sprinkled roads and another 50 miles of oiled roads. He said maintaining roads is a challenge with the tons of hay, beans, beets, and grain hauled over them every year, “try as we might our roads are bound to be cut up.”

In 1903 more entrepreneurs began to sell automobiles. N. Vickers opened the Oldsmobile agency in Ventura in August, adding room for automobiles in his storeroom which held buggies. By the fall, Ventura County had its first Ford dealership. J.F. McIntyre selected the Ford because it “runs with less noise and jar than any machine on the market and is as near an electric as any gasoline machine can be.” Within a month, Oxnard got its first car dealership, also Ford. The Oxnard Courier called the machine “the very best that is possible to buy for a medium price.” Ben Virden bought the first one, a two passenger, two-cylinder vehicle for about $850. The newspaper continued to tout the vehicle: “It is said that a lead pencil can be set on end on the seat of a Ford machine and the vibrations are not sufficient to jar it down.” With Virden’s Ford, Oxnard had four automobiles, which would parade through town on Sunday afternoons.

Harry Hunt of Nordhoff, now Ojai, started an auto bus service. Hunt’s 34-horsepower vehicle carried nine passengers and made two round trips to Ventura daily. Roundtrip was $1.50, one-way was $1. Hunt’s bus service was promoted as a boon for “those dependent on the inconvenient accommodation of the railroad.” Ventura banker C.H. McKevett bought a Haynes-Apperson automobile to avoid “the uncertainties of lumbering local or luxurious limited trains.”

Free Press Said Autos Are Becoming Routine

Automobiles had become so common that the Free Press boldly suggested, “Automobiles no longer astonish our little boys…even our horses are getting used to them, yet it is no fun to meet one on the creek as some of our ladies have found. One of our citizens says he will have to get an auto for his wife, so she need not be the one to be frightened.”

A 1904 letter to the Free Press offered stunning insight into what would soon come, the demand for good roads. “The growing popularity of the automobile will have a decided influence on the road of the future. When the automobile shall have become as common and available as the ordinary road vehicle, as in time it certainly will…highways throughout the country will be improved and new ones will be constructed in localities not now accessible.”

Drivers were testing the limits of their new machines. In the summer of 1904, a two-cylinder Rambler set a record driving from the post office in Nordhoff to the Anacapa Hotel in Ventura in 50 minutes. A.G. Mattison attempted to climb the steep incline to Poli Street from Main Street. He was within a car length of the top when his steam-powered automobile rebelled and started going backwards down the hill. Mattison turned the machine into the sidewalk with such force it flipped over on its seat “with wheels spinning in the air.” Mattison was unhurt.

Trouble in the Passes

In July 1905 the Los Angeles Times reported ranchers in Santa Barbara County had formed a rifle brigade to protect the San Marcos Pass from automobiles. The steep pass had been used by the Chumash for thousands of years to connect the coast and the Santa Ynez Valley. It was the shortest route north out of Santa Barbara. This was the era of record setting attempts by motorists, setting the stage for conflicts between the speeding drivers and ranchers in Ventura and Santa Barbara counties. Ignoring county law, drivers used the pass for their record runs and frightened teams and caused runaways. The armed ranchers vowed to put an end to use of the road by the “devil machines.” Some members of the rifle brigade made a special trip to Santa Barbara to study automobiles and learn how to “puncture the works of the machine with a rifle ball and cripple the machine without injuring the occupants.” Santa Barbara Judge J. M. Taggert, while on business in Ventura, warned the Free Press about the ranchers, “They are the kind that shoot, and they know how to shoot too.”

Ranchers living around Casitas Pass reported similar problems with the “speed maniacs.” They held a meeting in Ventura where they complained that the road was too narrow in many places for two vehicles to pass. They said the “speed maniac” demanded the road and forced the rancher to back up or haul his heavily laden wagon into the brush. Ventura County supervisors had passed a largely ineffective ordinance prohibiting the use of automobiles in the pass. “We must put a stop to this violation of the law,” declared one prominent rancher at the meeting. “We built the road…what right have they to come here and make that pass a death trap?” The rancher called for drastic action, “Men, get your rifles and stop the first man that comes racing through the pass. We won’t have to stop many of them…but let us be quick with the teaching before they do any more damage.” The Los Angeles Herald reported, “when the long stream of wagons left the little city (Ventura) there was a rifle under each seat.” While there was plenty of heated rhetoric, no evidence has come to light that shots were fired on either pass.

The Oakland Tribune railed against the ineffectiveness of law enforcement. The editors pointed to a man who had received a lot of press attention with his attempt to drive from Los Angeles to San Francisco in “railroad time.” His attempt was on public roads and “violated the law of the state every foot of the way.” Yet people gathered at many points along the route to see him pass, including in Ventura County. The Tribune concluded, “Presumably there were sheriffs, constables, and district attorneys among the spectators, yet not the slightest effort was made to enforce the law.”

The Automobile Club of San Francisco proclaimed that the speed and endurance tests were “a menace to public safety.” The Los Angeles Herald described one man’s distain for rich automobile owners. “A rich speed maniac kills somebody. Is he arrested and locked in jail? Not much! The policemen bow to him and say, ‘Pass my lord.’ It is next to impossible to get a warrant out against them.”

The editor of the Free Press deplored forcing the Southern Pacific railroad to run its trains at eight miles per hour though Ventura when automobiles are racing through the streets “at all hours of the day and night at double that speed.’

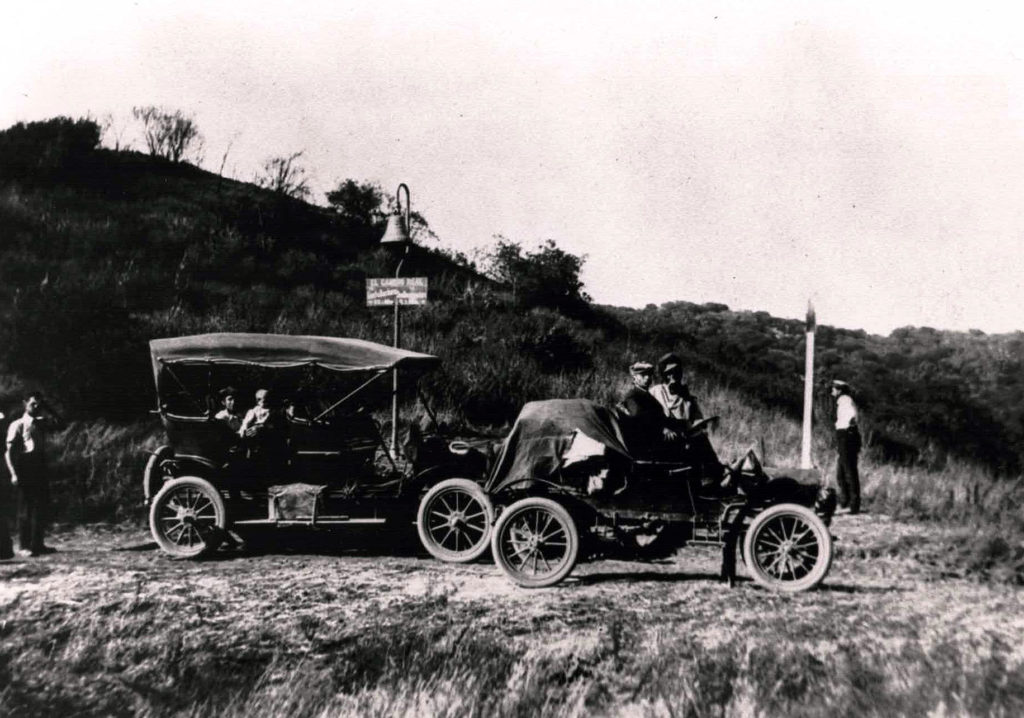

One organizer promoted an endurance test as a “pleasant outing.” In August 1905, 50 automobiles set out from Los Angeles, following 80 miles of roadway that had been sprinkled with confetti to mark the route. The autos left three minutes apart and could not travel faster than 15 miles per hour. They couldn’t pass the car in front of them unless there was a breakdown. Each vehicle left Los Angeles with 600 points. Points were deducted for delays caused by breakdowns and points were lost if the driver was “scorching” (speeding) and arrived in Santa Barbara early.

Ventura residents were developing a love-hate relationship with the automobile tourists. While happy to sell the travelers food and supplies, they resented drivers speeding through town and didn’t react well to criticism. Los Angeles mining executive H. V. Gleason wrote the Santa Barbara Press in 1905 complaining, “It is a shame that the authorities in Ventura County do not post some signs to direct automobilists who are coming over the roads.” The Free Press responded, accusing the “speed mad” drivers of going too fast to see the existing signposts.

Prosperous Lima Bean Farmers Eye Automobiles

While cars were still expensive for the average person, Ventura County lima bean farmers were emerging as a group with increasing disposable income. Sheridan, writing in the Free Press, noted it was the prosperous bean grower who could “afford to ride in power wagons.” He penned a poem about a grower’s yearning for an automobile.

Now, mother, I’m determined.

An’ I want no talking back –

To get a brand new auto

When the beans is in the sack. …

Our neighbor Dixon’s got one,

A regular crackerjack;

He says ‘twas limas bought it;

When he got them in the sack. …

You bet she’ll be a hummer,

Bright red and all shellac;

An’ Dixon’s won’t be thirty cents

When the beans is in the sack.

One Santa Paula automobile owner, L.B. Hogue, took exception to published remarks about the “utter disregard of the sudden rich for the rights of the people who cannot afford or do not ride in an automobile.” The newspaper supported Hogue and said for “the local auto owners there is nothing but praise nor can any man for a moment find fault with them and the way they run their machines.”

Price Gouging at the River Crossing

A new controversy erupted between out-of-town travelers and Ventura County ranchers and farmers. The President of the Southern California Automobile Association, W. M. Garland, complained the Ventura River crossing at Casitas Pass had been dug out and strewn with boulders, causing automobiles to get stuck. Garland further claimed that predatory farmers waited behind the trees with a team of horses “and all the paraphernalia convenient for immediately taking the automobile out.” He said the farmers were charging exorbitant fees to pull the autos out of the muck. “The minimum charge for the five minutes work is $5 (about $160 today) and in some cases $10 or $15 is charged.” J.B. Train, who lived close to the crossing called Garland’s charges “unqualified falsehoods,” adding the stuck machines are “monsters” and can’t be budged with fewer than four horses. “We have to wade into the river to hitch on and we are wringing wet from toe to crown before the job is done. The price we invariably ask to do this work is not exorbitant.” Garland’s claims were dismissed by the Free Press editors, “With all due respect to Mr. Garland, the Free Press believes he is mistaken and in vulgar parlance is talking through his hat.”

Travel over Casitas Pass was never routine. Mr. and Mrs. H. J. Huiskamp of Montecito were being driven down the grade when the brakes on their big Thomas automobile failed near the top. Their driver kept them on the road, but the speed kept increasing and they feared a “wild plunge down the mountainside.” Finally, at a horseshoe bend, the driver turned the car into the inside bank. The car flipped over, and all three occupants were thrown out. Everyone was uninjured except Mr. Huiskamp who had bad bruises and scratches. The couple spent the night at the Rose Hotel in Ventura and had their badly damaged car shipped by rail back to Santa Barbara the next day.

Autos Become More Popular and Powerful

By 1906 Santa Paula had about 2,200 residents and 30 automobiles. The Free Press reported automobile ownership per capita was greater in Santa Paula than in any town in the country. The newspaper said Santa Paula should be proud of its “large number of lady autoists” and printed the names of nine women who had become “expert drivers.”

A feat that had seemed impossible a couple of years earlier was performed by Los Angeles auto salesman Charles Capito. He ran his big Aero car up Palm Street, between Main and Poli Streets in Ventura. Not only did the 4-cylinder, 21 horsepower auto make it up the steep hill three times, it also backed up and down the hill.

The powerful new cars, especially the higher end models, were still priced out of reach for most people in the county. In 1907 T.W. Sturgis bought a seven passenger, 40 horsepower Maxwell touring car with all the “first class equipment” for $3,300, a sum equal to $105,000 today. A more modest Maxwell, with 20 horsepower, cost less than $1,500 and was advertised in the Free Press as “perfectly simple, simply perfect,” and ideal for beginners who had never owned or operated an automobile.

Winter Storms Trigger Desire for Better Roads

Nature at its worst helped to accelerate the already growing desire for better roads and bridges in the county. There was record rainfall during the winter of 1907. The county had just completed the $30,000 Sespe Highway bridge and called it one of the finest pieces of engineering work west of the Mississippi. But with over 20 inches of rainfall between November and January, flooding was wreaking havoc on roads throughout the county. Supervisor Thomas Clark reported the Casitas Pass Road was washed out in places and blocked by huge boulders. He saw trees standing in the road “as if they had always grown there.”

There was widespread damage to roads in Camarillo, Moorpark, and Oxnard. A bridge between Somis and Moorpark was wiped out. After an inspection tour, county supervisors said they could not estimate the cost of the damage. By March, there had been 25 inches of rain and high water had cut off the community of Bardsdale near Fillmore. To reach Ventura, residents Willis Burson and D.C. Love had to travel over the mountains to Moorpark and from there take a train to the city. Burson and Love joined leading citizens and petitioned the Board of Supervisors for a bridge to cross the Santa Clara River between Fillmore and Bardsdale.

In late March representatives from every part of the county met with county supervisors in Ventura and asked them to hold a bond election to fund bridges and permanent road improvements. The supervisors’ meeting room was packed, even though storm-damaged roads and high rivers had prevented many interested people from attending. Santa Paula citrus rancher Teague told the supervisors that good roads were the most important need of the county. He called it “disgrace” that such a rich country should have such poor roads. He was convinced county residents were willing to pay for good roads and bridges. But the million-dollar price tag was shocking.

The state legislature set up a framework for the improvement of public highways, the roads connecting cities and counties. The “Good Roads Bill” required counties to appoint a three-member highway commission. The commissioners would investigate the condition of public highways and determine which should be improved. Their findings were presented to boards of supervisors and if they approved, they called bond elections to fund the improvements.

A prominent Ventura businessman, Frank Barnard, began promoting the idea of a beach road between Ventura and Santa Barbara. Barnard called the Casitas grade a “wreck” and said something must be done to make travel between the two cities possible. Barnard underestimated the cost and complexity of building a beach road, saying “the whole thing has been laid out so well by nature that it is thought a small sum of $25,000 will do the work.” The Free Press editorialized that while there was growing interest in a coast highway, it would not be feasible without a bridge over the Ventura River at the foot of Main Street. “While the movement for voting bonds is being considered, why not include money for a good bridge right here at home?”

Twelve Miles of Streets and Every Mile Paved

The City of Ventura had an urgent need for street repair. Winter storms had made East Main Street impassable; Santa Clara and Front streets were almost as bad. In July 1907 surveyor J. B. Waud shocked the trustees when he told them it would cost $119,000 to pave the city’s streets. The cautious trustees decided to send Waud to Los Angeles to investigate an innovative process known as petrolithic paving. Four to six inches of soil was dug up. It was soaked with oil and then tamped with a special spiked roller. After two or three treatments the surface was packed almost as hard as cement. Waud became a convert. He saw streets that had been paved five years earlier that “seem today in perfect condition; they are almost noiseless, dustless and afford excellent foothold for horses.” Ventura would go a step further and replace the top two inches of soil with gravel or crushed rock for added durability.

Trustees enthusiastically approved $122,500 to pave every street in the city. Ventura’s paving project would take more than two years to complete. When it was done in November 1909, the Free Press memorialized the moment with a banner headline, “Twelve Miles of Streets and Every Mile Paved.” The city staged a four-day jubilee in celebration of the accomplishment featuring concerts, dinners, speeches, a horse show, an automobile parade and perhaps the most curious, a dynamite detonation, providing “[i]llumination of hills with red fire.” The events drew locals and out-of-towners poured in by train and automobile. The Free Press “conservatively” estimated 10,000 people lined the streets for the grand parade.

The good roads fever sparked a demand for roads and bridges that exceeded the money available to pay for them. Saticoy, Bardsdale, Piru, Santa Paula, and Nordhoff all asked county supervisors for bridges. Supervisors knew if they funded all the bridges, there would be little money left for road improvement. Without the road projects, they feared voters would reject the bond issue. The Free Press continued to press the need, “Ventura County is no longer an infant, we have passed the ‘creeping age,’ we are up and going. Make the roads smoother and speed will be greater; give us bridges and we can haul our oranges to the packing houses before they rot or get so large that no one wants them.”

Ventura County Supervisors had a new problem when the contractor building a bridge over the Ventura River at Casitas Pass walked off the job when it was nearly completed. Original iron work had gone into the river during the big winter storms and new iron was used to complete the bridge. Local iron and lumber companies were owed over $10,000 by the contractor, Oakland-based Burrell Construction. Burrell was owed $12,000 by the county, but it was not payable until after the job was finished. The cement floor of the bridge still had to be covered with asphalt and the approaches needed to be completed and fenced. The supervisors hired another firm to finish the work and opened the bridge in November.

In September 1907, the Ventura County Good Roads Commission held a convention and invited six delegates from each of ten road districts in the county. They recommended holding a bond election for roads and bridges “as soon as possible.” But before the end of the year, everything was put on hold because of the “Panic of 1907.” A series of bad decisions had caused widespread public distrust in the banking system and triggered a frenzy of withdrawals. Over a three-week period starting in mid-October, the New York Stock Exchange fell almost 50% from its 1906 high. The Free Press agreed the time was not right to take on more indebtedness believing that “good times will come again. Until they do, however, it is just as well…that we go slow.”

The First Auto Club Road Maps

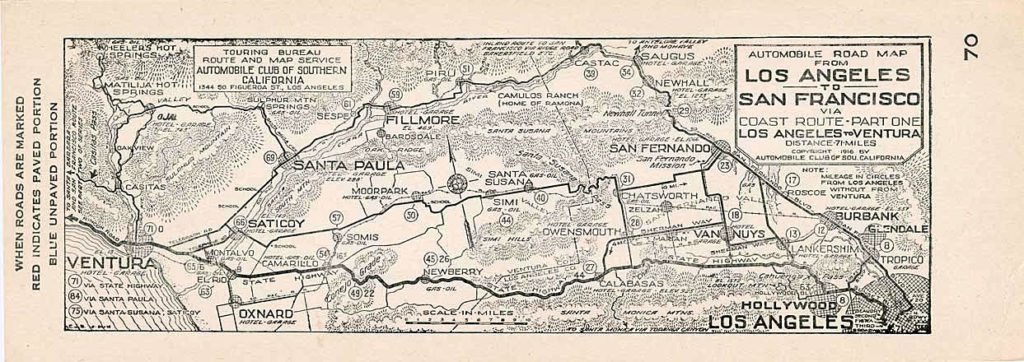

The Automobile Club of Southern California placed 700 redwood guideposts with signs designed by travel journalist Charles Fuller Gates. The signs noted important features on 500 miles of road including hills, turns, ditches, town limits and eventually the best hotels, repair shops, and places to buy gasoline.

By the summer of 1907 Santa Paula had 42 automobiles. The newspaper wrote that Ventura had 20 “that we can count off hand.” The maker of Diamond Tires projected 7,000 automobiles would be sold in California in 1908.

Ventura had its first collision between a train and an automobile in 1907. Machinist A. Palm was thrown from his car into an embankment when it was struck by the southbound Coast Line Limited at the Fir Street crossing. Palm had broken ribs and bad bruises. At first, he said he had attempted to cross the track in front of the train but miscalculated the distance. A day later he changed his story and claimed boys in a Halloween prank had put his automobile on the track and he was trying to move it.

A young Ventura man, Eugene Kimball, an expert who understood every automobile part “like a professional” broke his arm in two places while cranking his car at Mercer’s Garage. A Santa Paula man, probably less of an expert, escaped serious injury when he tried to fill the gas tank of his automobile while holding a lighted lantern in one hand and the gas can in the other. Quick work by his neighbors prevented a barn and outbuildings from being destroyed by the resulting explosion and fire.

End of An Era

In May 1909, as the paving of Ventura’s streets neared completion, another event marked the end of an era. Town trustees adopted an ordinance prohibiting the hitching and feeding of horses on the streets. One trustee called it a nuisance and said Oak and California streets were being turned into livery stables. Another trustee, Floyd Shaw said, “When our streets are finished, it will be no place for them.” A lot was rented near downtown and horse owners were required to hitch their animals in the town corral.

As roads improved, speeders were more determined than ever to break records. Witnesses were aghast when Los Angeles auto dealer Huntly Gordon roared into Ventura on Thompson Boulevard at 80 miles per hour. The car was airborne for 20 feet going over a culvert. At one downtown intersection his Stearns racer skidded and almost overturned. He was last seen leaving town as “a pale gray streak in a cloud of dust” heading north. The town marshall phoned the Santa Barbara police chief. The chief was waiting for Gordon with the Ventura warrant and caught him “fracturing the Santa Barbara speed limit” as well. He was taken before a justice of the peace and fined $100. The Ventura marshal took the morning train to Santa Barbara, arrested Gordon and had him drive them back to Ventura. Gordon pleaded guilty in Ventura and was fined another $100 (over $3,000 today.) The story escalated when the Stearns Motor Company ran an ad in the Sunday Los Angeles Times. It touted Gordon’s record run and suggested the company would pay the hefty fines. The editors of the Free Press accused the company of endorsing anarchy by shamelessly promoting speed tests while “taking a chance on the commission of murder.” An editorial concluded that while most people didn’t ride in automobiles, “the great mass pays the taxes to take up the bonds issued to build the roads. It is the lives and property of the great mass that are at stake in this war on speed maniacs, and it must be a war of extermination – not of the maniacs, maybe, but most assuredly on the practice.”

Some racers tried to take the legal route. J. A. Brassey of the Pioneer Auto Company of San Francisco asked Sheriff Edmund McMartin for permission to break both county and Ventura city speed limits in a record attempt from San Francisco to Los Angeles. Brassey offered to flag the roads and put out notices of when the run would take place. The sheriff and the town marshal concluded they did not have the authority to allow the speed limit to be broken for the purpose of a speed test. Ultimately, McMartin escorted Brassey through town at the speed limit. The marshal jumped on the running board of the big, red Thomas Flyer as it passed the waving crowds. Brassey still broke the record by 32 minutes.

Citizens Organize to Enforce Speed Limits

Ventura town trustees had just agreed on new speed limits. After some debate, the limit was set at 10 miles per hour except on Thompson Boulevard where it was set at 20 miles per hour, the same as the state speed limit. The next year, Oxnard would enact a 15 mile per hour limit. By the end of 1909 citizens began to take an active role in enforcing speed limits. Five men, W.H. Barnes, James Caruthers, Fred Foster, A. Greenfield Poplin, and Ben Dudley appeared before board of supervisors to protest the behavior of the “speed maniacs.” Barnes said state laws regarding speeders should be enforced “before some child or someone else is killed on the Avenue.” Poplin had long complained to anyone who would listen about speeders on the Avenue. He and an associate staked out a half mile stretch of the Avenue and timed cars. When Poplin turned in Ralph Ogilvie for traveling at more than 40 miles per hour, his was the first arrest for speeding on the Avenue. Ogilvie was fined $10. Poplin and the Ventura Avenue “detectives” would file complaints against anyone driving faster than 25 miles per hour. Eventually, more citizens, “armed with one of the finest stopwatches” joined in the crackdown.

A Santa Barbara auto dealer, A.W. McCreedy, pleaded not guilty to a charge of speeding on the Avenue. He appeared in court with a man representing himself as an official of “some automobile club or another.” He claimed the judge had a history of levying excessive fines and threatened to have Ventura taken off the automobile map of California. McCreery demanded a jury trial and was represented by State Senator L.H. Roseberry. The auto dealer maintained he had driven the route with dozens of new cars, but never exceeded the speed limit for fear of overheating the engines. He claimed this car had a slipping clutch and despite holding it as well as he could with his foot, the engine was racing. Poplin testified he’d clocked McCreedy going faster than 30 miles per hour. Senator Roseberry ridiculed Poplin in front of the jury and said if his “blackballing” kept up, Ventura would get a black eye from the motorists of California. District Attorney Don Bowker replied he would rather be blackballed by motorists from Los Angeles to Santa Barbara “than to have one woman or child lose a life at their hands.” The jury agreed and McCreedy was convicted.

Another speeder’s court battles dragged on for over two years. Cadillac speed specialist George Adair set a record from San Francisco to Los Angeles in December 1910, violating speed laws along the way, including in Ventura County. A judge found Adair guilty and assessed a penalty of $50 or 50 days in jail. Adair appealed, appearing twice in superior court and three times in appellate court. He had exhausted his appeals by the summer of 1912. Still, it took a visit by the Ventura constable to Adair’s Los Angeles home to get the man to finally “bring out the coin.”

Another Los Angeles man thought he’d fooled the law when he rushed a supposedly sick youth from Matilija Springs to a Los Angeles hospital. J. Hauser suspended a cot from the roof of a car in which the “sick” victim was riding. He slapped a fake Red Cross symbol on the wind shield. When a complaint was filed in Ventura, Hauser was brought back to explain himself to a judge. It turned out the young man “in dire straits” had sprained some of the muscles and ligaments in his back, but not seriously enough to warrant a high-speed trip to the hospital. Hauser was fined $15.

Mound resident J.A. Peters wrote the Free Press objecting to people throwing pop and beer bottles in the roads. Peters said the bottles were crushed by passing wagons. The glass, he complained, damaged expensive automobile tires. His suggestion: “It seems to me persons who have bottles to throw away could just as easily toss them to side of the road as to drop them in the middle of it.”

While numbering in the dozens only a few years earlier, by the end of 1911, there were 600 automobiles in Ventura County. It was estimated another 300 would be purchased in 1912. Prices were dropping. The basic runabout that sold for $900 in 1910 cost $590 in 1912. When Henry Ford began producing the Model T in 1913, prices dropped as low as $290. The automobile was becoming an affordable necessity for average Ventura County residents.

Coastal Highway Goes from Dream to Reality

More cars meant more pressure for road improvements. J.M. Sharpe of Saticoy told the Board of Supervisors, “Ventura Boulevard has spoiled us for good roads. We want the same kind of roads everywhere.” No project was more challenging, and at times elusive, than the dream of building a coast highway between Ventura and Santa Barbara. There was widespread support in both Ventura and Santa Barbara to have a permanent road along the coast, especially when winter rains made Casitas Pass treacherous. All the land was in Ventura County, so no Santa Barbara County tax money could be used. In addition, the sparsely populated mountain district didn’t generate enough of a tax base to pay for the improvements. The Free Press supported the idea, while noting that the project would likely have an “immense cost” and added “there should be state aid in the construction of the road.”

Meanwhile a group of five Santa Barbara entrepreneurs proposed building a $200,000 private toll road along the beach parallel to the Southern Pacific tracks. They asked for a 50-year franchise with an option for the county to buy back the road in the future. The board of supervisors rejected the idea.

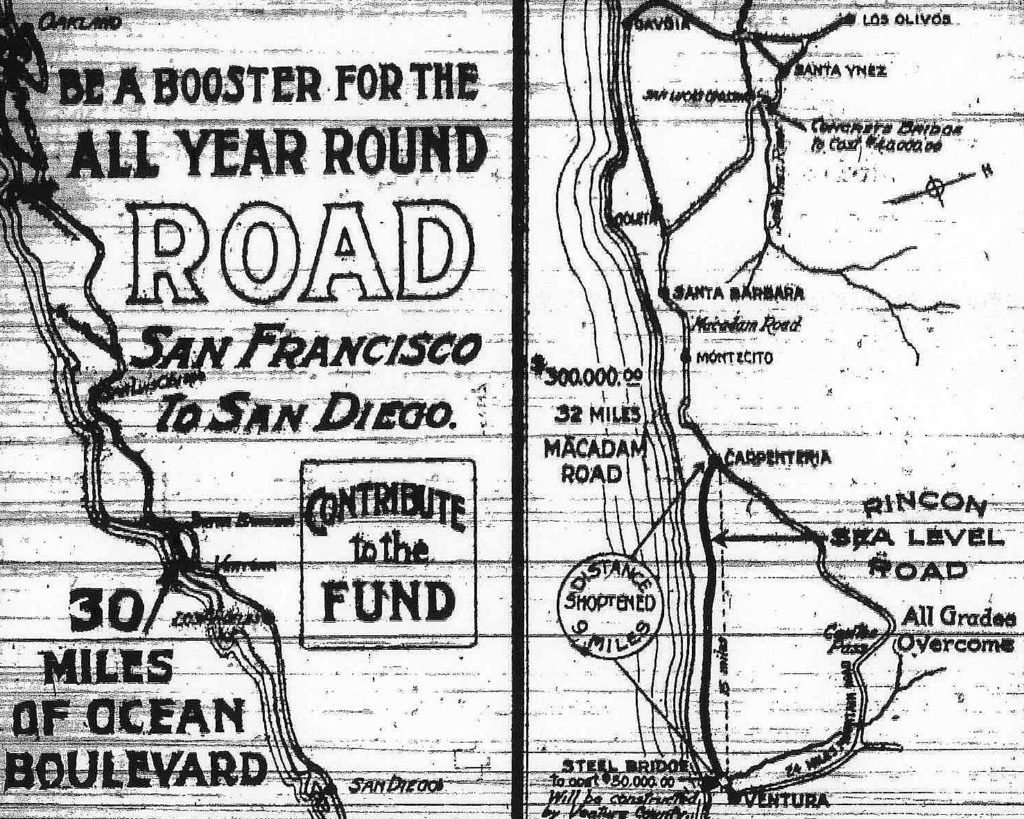

In early 1911, civic boosters started raising funds for the road with private donations. Venturans E.P. Foster, John Lagomarsino, W.A. Hobson, and Sol N. Sheridan were leaders in the fundraising effort along with Franklin E. Kellogg, secretary of the Santa Barbara Chamber of Commerce. The pitch for donations promised the road would be “one of the scenic wonders of California.” The Free Press even suggested it would make California’s coast even grander than the Italian Riviera. As a practical matter, the road would supersede the Casitas grade and shorten the distance to Santa Barbara by nine miles. Ventura County Supervisors agreed to contribute $50,000 and it was thought the donations would raise the additional $50,000 needed to bridge the Ventura River and grade the sea-level road, creating a grand, 30-mile ocean boulevard.

Increasing attention focused on state funding. In December 1910, the “State Highways Act” took effect. It authorized the issuance of $18 million in bonds for a “continuous and connected state highway system.” It created a three-member California Highway Commission to construct and maintain the highway system. The Free Press urged Ventura County to send a delegation to Sacramento to lobby for a share of bond funds, saying “There can indeed be no proper coast highway without the Rincon Road and bridges over the Ventura River.”

Numerous small donations came in. A public appeal in Ventura raised $4,750 in one day when “almost every man approached” promised “as much as he could afford to give.” The Santa Barbara Chamber of Commerce appealed directly to its members asking for a $5 donation to raise $1,500. The Secretary of the Automobile Club of Southern California, Sybel Geary, called the road “one of the most important undertakings” in the state. The club donated $2,500.

Work began in November 1911 when enough, but not all, of the money was raised. One million board feet of lumber was ordered for the causeways. They would be built on eucalyptus pilings driven above the high-water mark. The three-inch timber planking of the causeway was covered with asphalt. Other parts of the road followed the Southern Pacific Railroad’s right of way along the coast.

Six months later, $35,500 had been spent on the road and 2,000 feet of decking still needed to be completed. Funds were exhausted and the work came to a halt. The joint county committee overseeing the road asked the State Highway Commission to take over the Rincon project. Ventura County Supervisors followed with a similar resolution and pointed out that the county had already signed a $50,000 contract for construction of a key component of the coast highway, the concrete arched bridge over the Ventura River just west of the Ventura city limits.

County Supervisor Clark made three visits to the Commission offices in Los Angeles and conducted critical negotiations with Commissioner N. D. Darlington. In late August 1912, the State agreed to take over the Rincon Road and asked for bids to complete the work. The Free Press called it a “great triumph.” The state began work on a 6,000-foot-long planked trestle road about ten feet above the beach. A sea wall would be built to safeguard the road.

By November, the road was “soft in places, rough in others,” but passable. At the Ventura River crossing a temporary bridge was in place. The road was inspected by the four men largely responsible for its completion: Supervisor Clark, S. Sheridan, Good Roads pioneer A. McAndrew, and board of supervisors’ advisor George Farrand. Farrand had opposed the toll road idea and correctly predicted the road would ultimately be taken over by the state. The four men made the 29-mile trip from the Bank of Ventura to the Arlington Hotel in Santa Barbara in 1 hour and 30 minutes. Three thousand people attended the formal opening of the road on November 24, 1912, celebrating with a “monster barbecue.” Drivers from all over Southern California were in attendance, including 2,000 from Los Angeles.

Clearly there was a rush to open the road. Drivers immediately complained and contracts were let for several projects to make the coastal road suitable for automobiles. Heavy rain in 1914 washed out one side of the planked roadway. One driver picked his way through the beach and back to the road by getting traction on spots where kelp had been deposited on the sand.

In 1914, the California Supreme Court rejected challenges to a new motor vehicle law that insured there would be a fund for road improvement and maintenance. Under the old law there was no provision for taking care of the state’s $18 million highway system. The state would spend hundreds of thousands of dollars improving the road. Even before the work was completed, the Free Press in 1915 complained that the Rincon highway, while still in “its infancy,” had become a speeder’s racetrack.

While Ventura County’s quick transition from horses to cars was marred with conflict, sometimes armed, it also ushered in an era of unprecedented investment in roads and bridges. An automobile-based economy led to new service jobs and a state highway system that would connect the county with the rest of the state. It also facilitated a population boom that would have longstanding and profound impact on the growth of the county.

Make History!

Support The Museum of Ventura County!

Membership

Join the Museum and you, your family, and guests will enjoy all the special benefits that make being a member of the Museum of Ventura County so worthwhile.

Support

Your donation will help support our online initiatives, keep exhibitions open and evolving, protect collections, and support education programs.

Bibliography

- “100 Years and Miles to Go.” Los Angeles Times. Last modified July 12, 2000. https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-2000-jul-12-hw-51296-story.html.

- “Before Paved Roads, There Is the Auto Club.” Cal@170 by the California State Library. Last modified September 9, 2020. https://cal170.library.ca.gov/december-13-1900-before-paved-roads-there-is-the-auto-club/.

- “The Casitas Pass Stagecoach Road.” Ojai History – Sharing the History of the Ojai Valley. Accessed July 6, 2022. https://ojaihistory.com/the-casitas-pass-stagecoach-road/.

- Gidney, Charles M., Benjamin Brooks, and Edwin M. Sheridan. History of Santa Barbara, San Luis Obispo and Ventura Counties, California. 1917.

- “The Golden Triangle-The Spooner Trail.” Ventura Breeze. Last modified June 17, 2020. https://venturabreeze.com/2020/06/17/the-golden-triangle-the-spooner-trail/.

- “Judith Dale: San Marcos Pass – A Historic Gateway to Santa Barbara County.” Lompoc Record. Last modified March 22, 2022. https://lompocrecord.com/lifestyles/columnist/judith-dale-san-marcos-pass-a-historic-gateway-to-santa-barbara-county/article_d4cf8d35-50a3-5a86-90b5-424607d56cd0.html.

- Los Angeles Herald. “Big Club Scores ‘Speed Maniacs’.” August 12, 1905, 9.

- Los Angeles Herald. “Cold Lead for Auto Speeders.” July 31, 1905, 5.

- Oakland Tribune. “The Auto Speed Mania.” August 1, 1905.

- Oxnard Courier. “Editorial.” July 20, 1903, 4.

- Oxnard Courier. “First Automobile Agency for Oxnard.” October 30, 1903, 1.

- “Roads.” SCVHistory.com | Santa Clarita Valley History Archives | Research Library | SCV History in Pictures. Accessed July 6, 2022. https://scvhistory.com/scvhistory/chs1996goodroads.htm.

- “Southern California Automobile History: The Era of the Horseless Carriages.” San Bernardino Sun. Last modified July 25, 2017. https://www.sbsun.com/2016/08/22/southern-california-automobile-history-the-era-of-the-horseless-carriages/#:~:text=The%20first%20manufactured%20passenger%20automobile,Gaylord.

- “Traffic On Ventura Avenue: Horse and Buggies to Roller Skates.” Museum of Ventura County. Last modified July 19, 2021. https://venturamuseum.org/journal-flashback/traffic-on-ventura-avenue-horse-and-buggies-to-rollerskates/.

- Ventura Free Press. “A Long Automobile Trip.” August 10, 1900, 2.

- Ventura Free Press. “A Protest to Supervisors.” July 20, 1906, 8.

- Ventura Free Press. “Accident in Casitas.” June 22, 1906, 8.

- Ventura Free Press. “Adair Fights Case Goes to Court of Appeals.” May 26, 1911, 3.

- Ventura Free Press. “Advantages of the Rincon Sea Level Road to the Traveling Public.” July 28, 1911, 8.

- Ventura Free Press. “An Automobile Incident.” February 20, 1903, 2.

- Ventura Free Press. “At the Courthouse.” March 8, 1907, 7.

- Ventura Free Press. “Auto Speed Maniac Fined Cost $200 to Break Record.” April 30, 1909, 8.

- Ventura Free Press. “Automobile Club People Raise Coin at Los Angeles.” August 6, 1911, 8.

- Ventura Free Press. “Automobile Tires Endangered When Bottles Are Thrown into the Road.” August 4, 1911, 5.

- Ventura Free Press. “Automobiles Coming.” August 4, 1905, 1.

- Ventura Free Press. “Bad Roads.” February 1, 1907, 1.

- Ventura Free Press. “Bad Roads.” January 25, 1907, 8.

- Ventura Free Press. “Big Crops Mean More Automobiles.” October 13, 1911, 6.

- Ventura Free Press. “Broke His Arm.” December 27, 1907, 5.

- Ventura Free Press. “California’s Coast Grander Than Italy’s Famed Rivera.” July 21, 1911, 1.

- Ventura Free Press. “Comment.” April 8, 1904, 5.

- Ventura Free Press. “County Unanimous for Good Roads.” March 29, 1907, 1.

- Ventura Free Press. “Daring Trip Over the Rincon in An Auto.” January 9, 1914, 8.

- Ventura Free Press. “Editorial.” June 5, 1903, 4.

- Ventura Free Press. “Editorial.” December 30, 1904.

- Ventura Free Press. “Editorial.” July 20, 1906, 3.

- Ventura Free Press. “Editorial.” November 30, 1906, 4.

- Ventura Free Press. “Editorial.” August 31, 1906, 4.

- Ventura Free Press. “Editorial.” May 14, 1909, 4.

- Ventura Free Press. “Editorial.” May 7, 1909, 4.

- Ventura Free Press. “Editorial.” December 1, 1911, 4.

- Ventura Free Press. “Everyone Favors Autos but Oh You Speed Maniacs.” December 17, 1909, 5.

- Ventura Free Press. “Fake Red Cross Fails.” September 1, 1911, 3.

- Ventura Free Press. “First Arrest for Speeding on Ventura Avenue.” December 24, 1909, 3.

- Ventura Free Press. “George Adair, Speeder, Must Pay Fine.” May 3, 1912, 3.

- Ventura Free Press. “Good Hill Climber.” November 16, 1906, 1.

- Ventura Free Press. “Good Roads Movement.” April 5, 1907, 1.

- Ventura Free Press. “Good Roads People in Convention.” September 13, 1907, 1.

- Ventura Free Press. “Happenings of A Week in The City and County.” July 28, 1911.

- Ventura Free Press. “Horseless Carriage.” October 4, 1895, 4.

- Ventura Free Press. “Hueneme Happenings.” December 25, 1896, 8.

- Ventura Free Press. “Hyde Chaffee Wants to Know About That Red Cross Auto.” August 25, 1011, 2.

- Ventura Free Press. “Immediate Work on Rincon.” March 10, 1910.

- Ventura Free Press. “Immediate Work on Rincon.” December 6, 1912, 1.

- Ventura Free Press. “In Legal Tangle.” August 23, 1907, 3.

- Ventura Free Press. “Kicking About Signs.” August 25, 1905, 8.

- Ventura Free Press. “Letter to the Editor.” June 24, 1904, 6.

- Ventura Free Press. “Letter to the Editor.” April 6, 1906, 4.

- Ventura Free Press. “Local Speeders Caught on the Avenue.” August 4, 1911, 5.

- Ventura Free Press. “Many Turns of This Legal Battle.” January 19, 1912, 8.

- Ventura Free Press. “May Take Rincon Road and Finish Its Construction.” June 21, 1912, 1.

- Ventura Free Press. “Miscellaneous Items.” August 22, 1902, 2.

- Ventura Free Press. “Miscellaneous Items.” April 25, 1902, 5.

- Ventura Free Press. “Miscellany.” June 22, 1900, 5.

- Ventura Free Press. “Money Still Needed for Rincon Road.” May 31, 1912, 2.

- Ventura Free Press. “Moorpark.” February 28, 1902, 7.

- Ventura Free Press. “More Gasoline Buggies.” August 16, 1907, 5.

- Ventura Free Press. “Need Bridge City Ticket.” March 8, 1907, 3.

- Ventura Free Press. “Needed His Gun.” November 13, 1903, 2.

- Ventura Free Press. “News from the Courthouse.” May 17, 1907, 3.

- Ventura Free Press. “News of Our Neighbors.” November 1, 1907, 6.

- Ventura Free Press. “Nordhoff.” December 11, 1903, 6.

- Ventura Free Press. “Nordhoff.” December 18, 1903, 6.

- Ventura Free Press. “Nordhoff.” April 8, 1904, 6.

- Ventura Free Press. “Ojai.” September 28, 1900, 6.

- Ventura Free Press. “Our City Trustees Favor State Aid for Coast Road.” February 12, 1909, 1.

- Ventura Free Press. “Oxnard Has Raised Speed Limit.” June 23, 1911, 2.

- Ventura Free Press. “Oxnard News.” April 18, 1902, 7.

- Ventura Free Press. “Oxnard.” June 26, 1903, 6.

- Ventura Free Press. “Oxnard.” November 6, 1903, 8.

- Ventura Free Press. “Petrolithic; What it Is, How Made, Success.” August 9, 1907.

- Ventura Free Press. “Piru Notes and Personals’.” November 22, 1901, 8.

- Ventura Free Press. “Preparing for the Bonds.” July 12, 1907, 1.

- Ventura Free Press. “Request to Commission to Take Rincon Road.” July 12, 1912, 3.

- Ventura Free Press. “Rifles for Autos.” July 28, 1905, 8.

- Ventura Free Press. “Rincon Beach Road Funds Fine Growth.” July 28, 1911, 1.

- Ventura Free Press. “Rincon Road is Opened Inspected by Venturans.” November 1, 1912, 1.

- Ventura Free Press. “Rincon Sea-Level Road Opened.” November 29, 1912, 1.

- Ventura Free Press. “Road Commission Waiting.” November 29, 1907, 3.

- Ventura Free Press. “Santa Barbara Motor Driver is Tried Here.” August 4, 1911, 3.

- Ventura Free Press. “Santa Paula Celebration.” July 5, 1901, 8.

- Ventura Free Press. “Santa Paula News in Brief.” May 30, 1902, 12.

- Ventura Free Press. “Santa Paula News in Brief.” August 1, 1902, 8.

- Ventura Free Press. “Santa Paula News.” March 21, 1902, 8.

- Ventura Free Press. “Santa Paula Notes.” March 13, 1903, 12.

- Ventura Free Press. “Santa Paula Notes.” February 13, 1903, 8.

- Ventura Free Press. “Santa Paula Notes.” July 3, 1903, 8.

- Ventura Free Press. “Saturday Night Reflections.” August 6, 1905, 4.

- Ventura Free Press. “Sespe Bridge is Accepted.” January 11, 1907, 2.

- Ventura Free Press. “Speed Ordinance.” May 21, 1909, 7.

- Ventura Free Press. “Speed Specialist Fined Fifty Will Appeal Case.” February 3, 1911, 3.

- Ventura Free Press. “Speedy Autos.” July 31, 1903, 6.

- Ventura Free Press. “Storm Damage in the Casitas.” January 18, 1907, 1.

- Ventura Free Press. “Struck by Train.” November 8, 1907, 8.

- Ventura Free Press. “The Beach Road.” February 22, 1907, 1.

- Ventura Free Press. “They Mean Business.” August 4, 1905, 8.

- Ventura Free Press. “This Week at The Courthouse.” June 7, 1912, 3.

- Ventura Free Press. “Triangle Trip.” May 2, 1902, 4.

- Ventura Free Press. “Uncle Sam’L.” May 10, 1907, 1.

- Ventura Free Press. “Ventura County Roads.” July 31, 1903, 3.

- Ventura Free Press. “Ventura Visitors and Ventures.” November 8, 1907, 5.

- Ventura Free Press. “Ventura Visitors and Ventures.” October 9, 1903, 5.

- Ventura Free Press. “Ventura to Have Good Streets Jubilee.” November 5, 1909, 1.

- Ventura Free Press. “Ventura’s Jubilee Begins.” December 3, 1909, 7.

- Ventura Free Press. “Victory For Home People.” August 30, 1912, 3.

- Ventura Free Press. “Want Road.” January 25, 1907, 8.

- Ventura Free Press. “Want Toll Road on the Coast.” September 24, 1909, 3.

- Ventura Free Press. “Wants Permission to Race on County Roads.” May 21, 1909, 3.

- Ventura Free Press. “Waud Says Bond Issue Most Ready to be Submitted.” July 19, 1907, 1.

- Ventura Free Press. “We’uns Too.” April 19, 1907, 1.

- Ventura Free Press. “Will Complete Bridge.” September 6, 1907, 3.

- Ventura Free Press. “Will Stop Stabling Horses in Streets.” May 21, 1909, 1.

- Ventura Free Press. “With Our Automobilists.” May 17, 1907, 8.

- Ventura Free Press. “Would Take Ventura Off the Automobile Map Of Southern Part Of The State.” July 14, 1911, 3.

- Ventura Free Press. “Editorial.” March 12, 1915, 4.