by Library Docent Volunteer Andy Ludlum

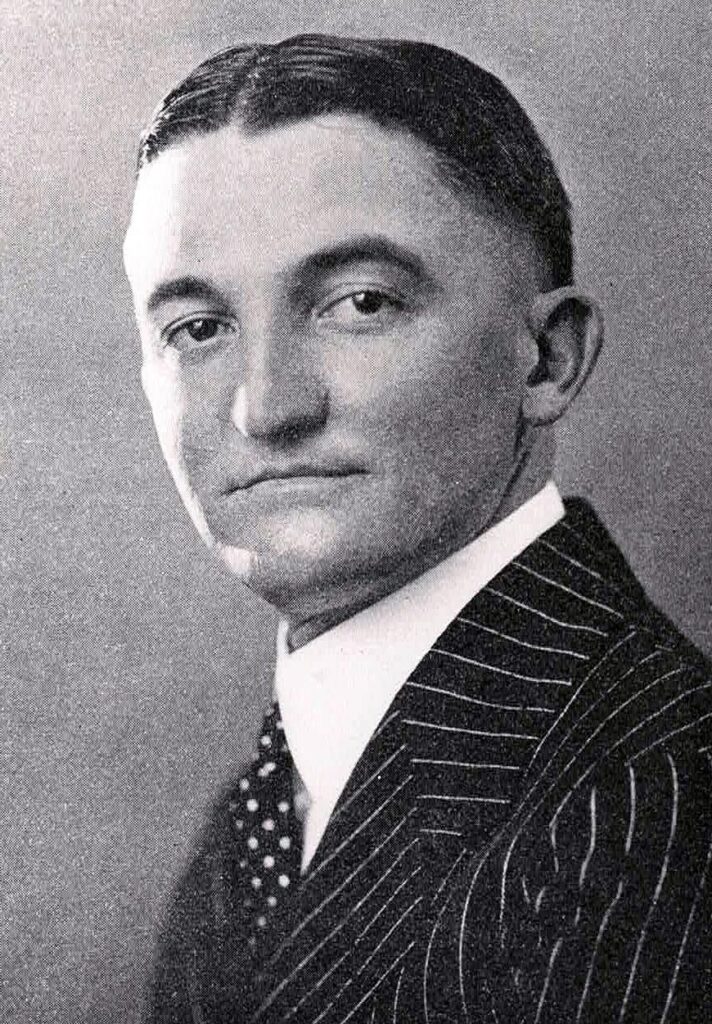

On July 28, 1924, when motions were called for in the case of the People vs. Jesse Mendoza in Ventura County Superior Court, court watchers were stunned when “a tall and stately woman” stepped inside the bar and answered, “ready for the defendant.” Mary Belle Spencer of Chicago became the first woman to represent a criminal defendant in Ventura County history. And this was no routine trial. It was the trial of man accused of committing one of the most gruesome and brutal murders anyone could remember. Spencer practiced law for decades and relished the attention she drew in legal circles. But despite her accomplishments and failures, she was invariably described in the newspapers as “the woman lawyer.”

Female Lawyers Were a Rarity

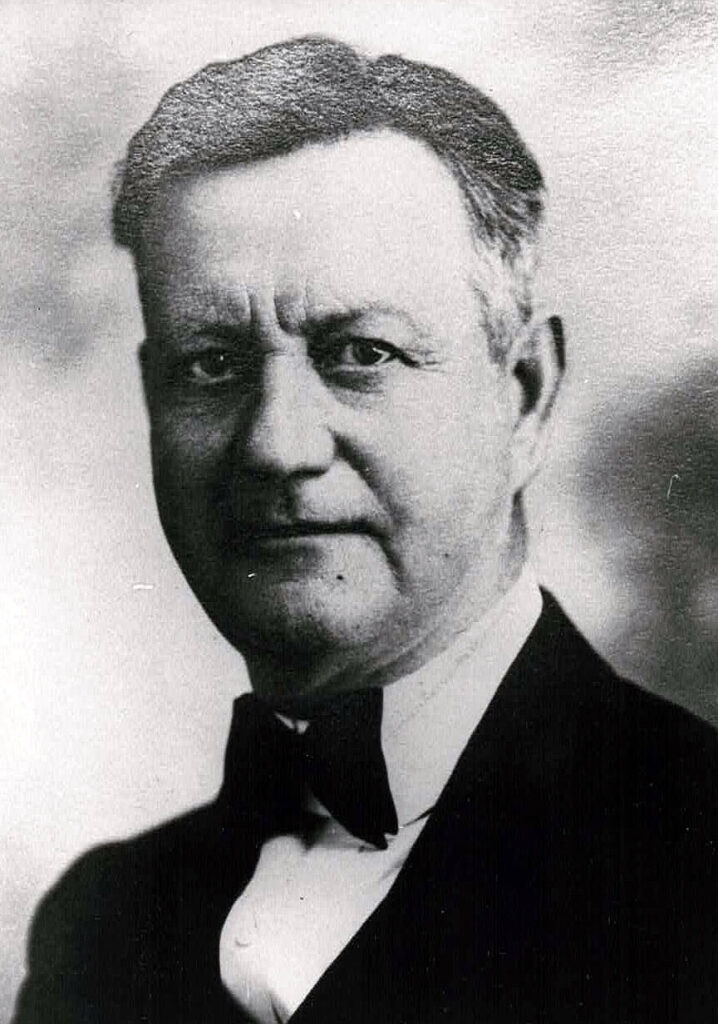

Mary Belle Withrow was born on August 9, 1882, in Platteville, Wisconsin. When Mary Belle was 12, she moved to Chicago with her mother and sister. There she married Dr. Richard Vance Spencer in 1910. Spencer was active with social and civic welfare work including what the Chicago Sunday Times referred to as “the work of Americanizing naturalized citizens.” She enrolled in one of the few law schools that admitted women, Northwestern University School of Law, and graduated in 1918, a time when the legal profession was an unusual career choice for women.

In 1920, there were 125,000 lawyers and judges in the United States. Of those, only 1,738 (.01%) were women. That year, when the 19th Amendment to the Constitution was ratified and granted all women the right to vote, all states began to admit women to the bar.

In California, Clara Shortridge Foltz had to lobby the state legislature and pressure the governor to pass the “Woman Lawyer’s Bill” in 1878, which opened the California state bar to women. Previously, it had been limited to “white male citizens.” When Foltz passed the bar exam, she became state’s first female lawyer.

During the 1920s, while the elite law schools admitted a few women, most attended part-time law schools for women, with classes often held at night. The new women attorneys faced severe obstacles. Many found it virtually impossible to find a job in law offices. Overqualified women often took jobs as stenographers or librarians in law firms. A few went into practice with their husbands or fathers in small local firms.

Spencer’s public career started when she was named as Cook County (Chicago) Public Guardian in 1918. A public guardian is a lawyer appointed to represent minor wards in court. Spencer promised the “bereaved children of Cook County…the conscientious work the fiduciary relationship requires.” Within a year, her handling of a juvenile court case caused a controversy. Spencer had sanctioned the wedding of a 16-year-old ward of the court and George Du Bok, purportedly the girl’s 50-year-old stepfather. Spencer defended her decision by claiming the groom was not the child’s stepfather, but just a man who lived with her mother. A judge found the explanation to be “a distinction without a difference” and took all juvenile court cases away from Spencer. She disputed the judge’s action but resigned in 1921. She said her law practice demanded her full attention.

After leaving the Public Guardian job, Spencer ran for Congress in a special election in 1922 to fill the unexpired term of the late William E. Mason. Spencer promised to oppose “any measure which will interfere with the personal liberty of people.” Spencer was one of six Republicans in the April primary, including another woman, Winnifred Mason Huck, the daughter of the late Congressman. Spencer came in last and was knocked out in the primary. Huck was elected in November and became the first woman in Congress from Illinois and the third woman to serve in Congress.

Spencer’s personal life attracted public attention. The birth of her daughters, Mary Belle, in 1919, and Victoria in 1921, raised what was then a new question: could a woman successfully combine motherhood with a career? Spencer insisted, “I’ve always maintained that a woman’s place is in the home long enough for her to attend to the welfare of her husband and children. After that, it’s where her inclinations lead her. And mine naturally led me to my office. But I didn’t desert my babies. I brought them with me and established them in the care of a trained nurse at a hotel across from the county building so I could be near them.” Spencer’s parenting style and relationship with her two daughters would spark the newspapers’ interest in her family in the years to come. In 1924, an urgent plea for help from the father of an accused murderer would bring Spencer to Ventura County.

The Brutal Murder

Early Friday morning, November 2, 1923, Joe Lopez, a 15-year-old schoolboy, walking near El Rio on the state highway to Camarillo, stumbled on the scene of one of Ventura County’s most gruesome murders. In an alfalfa field, about 75 feet from the highway, lay the body of man. His knees were drawn up to his chin. His face had been hit with such force that it was flattened, and his teeth were scattered about on his chest. A large blood-stained rock covered with hair was found near the body. Lopez rushed home to tell his sister who called neighbors and the police. After examining the scene, Undersheriff Harle Walker concluded the vicious attack had started on the other side of the road where he found tire tracks and the blood-stained handle of a hammer.

At a hastily called inquest, it was revealed that the body had gone undiscovered for at least 24 hours, leading investigators to conclude the murder happened sometime Wednesday evening. County Coroner Oliver Reardon identified the dead man as a “Hindoo,” 35-year-old S. T. Kahlly.

South Asian Discrimination and Exclusion

In the 1920s, any immigrant from South Asia was commonly referred to being a “Hindu” or “Hindoo,” a shortened version of their place of origin (Republic of India) which was then known as Hindustan. Kahlly was likely a Sikh. Most of the South Asian immigrants to California had come from the Punjab region in northern India. Eighty-five to ninety percent of these immigrants were Sikh, another ten percent were Muslim, and a very small percentage were Hindu.

Reardon said Kahlly first came to the country around 1908 as a special representative of his government sent to investigate the agricultural methods used in the United States. After delivering his report, he returned to the United States to grow rice and vegetables in the Sacramento Valley and in Stockton. Inquest testimony revealed that Kahlly had come to Ventura County to farm on land he rented from James O’Conner and from the Babcock company in Oxnard. He employed laborers to work on his farms.

The 1910 census showed half of the 5,424 South Asian immigrants in the U.S. lived in California. Most worked in the state’s agricultural areas including the lima bean and beet fields in Ventura County. While they excelled as laborers and farmers, they were quickly seen as an economic threat, taking away jobs from white men. They were targeted for discrimination and exclusion, following the precedents set with Chinese and Japanese laborers. The press inflamed racist sentiments by warning about an invasion by the “Turbaned Tide.”

A 1915 article in the Oxnard Press-Courier did not reflect the fear seen in other parts of the state. The paper noted “Hindus…have promoted themselves from working on hands and knees to farming operations.” The article explained a man named Fatha Singh had secured the necessary equipment and planned to farm on the J.M. Stewart ranch near Moorpark.

In 1906, Congress restricted naturalized citizenship only to “free white persons” and “persons of African nativity,” essentially excluding Asians from U.S. citizenship. The Oriental Exclusion Act of 1924 denied naturalization and citizenship to Asians in general from 1924 to 1943. California’s Alien Land Law enacted in 1913 held that “aliens” ineligible for citizenship could not own land in the state. The Supreme Court declared the Alien Land Law constitutional in 1923 and it remained California law until 1956.

First Leads Focus on a Red Oldsmobile

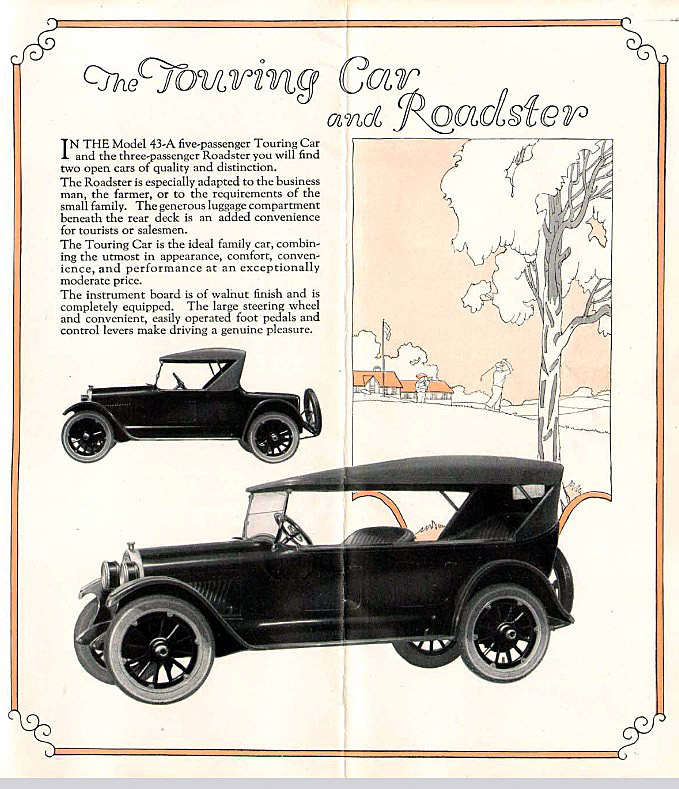

Testimony at the inquest began to piece together the facts of the murder. On the night before his death, Kahlly was in Los Angeles to pick up $250 to pay his workers. He left Los Angeles and returned to Oxnard at about five in the afternoon in a red 1923 Oldsmobile touring car that had been loaned to him by a business partner, Carl F. Bechdolt of Pasadena.

Bechdolt and Kahlly were vegetable farming on shares on land in Oxnard. Typically, the farmer and landowner enter an agreement where they share costs and revenue from the land. The landowner gives his land, and the farmer his work. Together, they share both the cost and profit. Kahlly was said to be an expert in truck gardening, raising vegetables for sale in the markets. He was last seen alive on Wednesday by his friend A. B. Chinta. Kahlly told Chinta he was heading back to Los Angeles.

Oxnard police constable Henry Helmold testified that Kahlly took his car out of a garage Wednesday evening for the trip south. He said a “Mexican” was watching Kahlly and suggested this man and a companion were the murders. Officer Louis Diedrich said he passed near the murder scene about 7:00 p.m. Wednesday and saw a car parked partly on the highway. He saw two men standing by the car. A half hour later he returned and saw the same two men.

Ventura County Sheriff Robert Clark admitted there were plenty of questions and few clues. Kahlly’s gold watch was left on his body. They also found $115 in Kahlly’s hip pocket. His side pockets were turned inside out. Sheriff Clark was unable to determine if Kahlly had paid some of his workers Wednesday or if the killer took some of the money and left in a hurry with the car. He asked the Automobile Club and Southern California police agencies to be on the lookout for the red Oldsmobile.

The Ventura Morning Free Press fed the idea that a “Hindu” was responsible for the murder, even though Sheriff Clark and District Attorney Edward Henderson said Chinta and Kahlly’s other “Hindu” friends had been cooperative and were not suspects in his murder. The newspaper suggested Kahlly had “picked up one the Hindu boys.” They knew he was carrying the payroll, waited until he reached the lonely spot near El Rio and then slugged him over the head. In a shockingly racist conclusion, the Free Press said, “The theory that a Hindu was responsible is advanced from the fact that it is believed that a white man would shoot the victim while a Mexican would use a knife.” The newspaper claimed Sheriff Clark was “making a careful check of Hindus in the county, particularly in the Oxnard and Camarillo district to determine if any are missing and also to learn the identity of those who can drive a car.”

Sheriff Clark was following a more promising tip, one that would take him on a nine-month manhunt back and forth across the U.S. – Mexico border. The break in the case was reported by the Simi Valley Star. According to their story, late on the Wednesday night of the murder, Arche Mahan, owner of Mahan’s Garage in Moorpark said, “two Mexicans got [him] out of bed to get some gas so that…they could take their aged and ailing mother to the hospital.” The men, he said, were heading south and were “evidently harassed and anxious to be on their way.”

Meanwhile, Kahlly’s remains were cremated at Rosedale cemetery and his ashes were picked up by a friend, Clara Cooley, who took the ashes to Stockton for burial. While the local newspaper editors didn’t know it at the time, Cooley was more than a friend, she had been Kahlly’s employee and business partner. It was revealed that Kahlly had left the Stockton widow “all his possessions” including a $25,000 life insurance policy. While in Ventura, Cooley promised she would “employ all possible means” to hunt down Kahlly’s killer.

News Grows Cold After Arrests Appear Imminent

Just two weeks after the murder, Sheriff Clark and District Attorney Henderson focused on two men. After returning from a three-day trip to “a southern locality,” Clark and Henderson announced they had identified the killers, though they refused to disclose their names and where they were located. They claimed to have enough evidence for a conviction and arrests appeared imminent.

Instead, the story disappeared from the newspapers. In late March 1924, almost five months after the murder, it was revealed Kahlly’s estate was worthless. The $25,000 life insurance policy left for Cooley had lapsed and there were no other funds or property, only $3,000 in claims filed against the estate.

The Lure of a Woman Leads to An Arrest

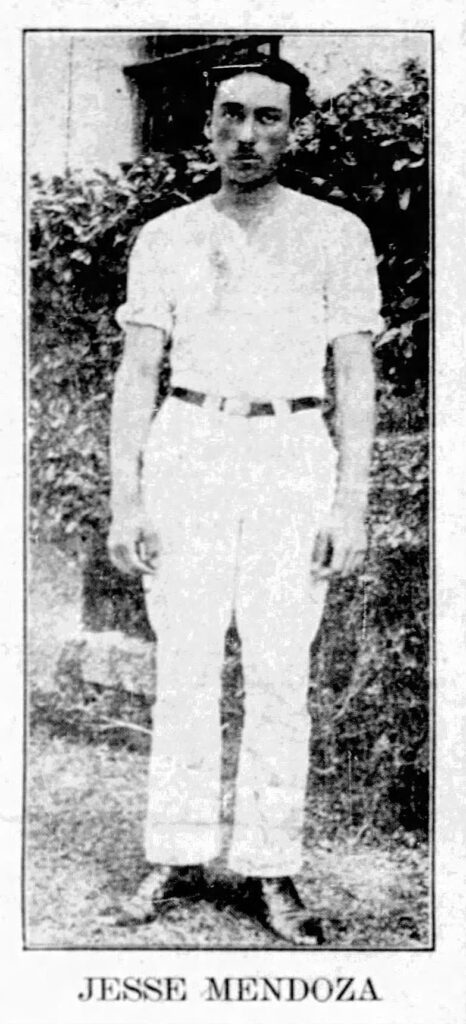

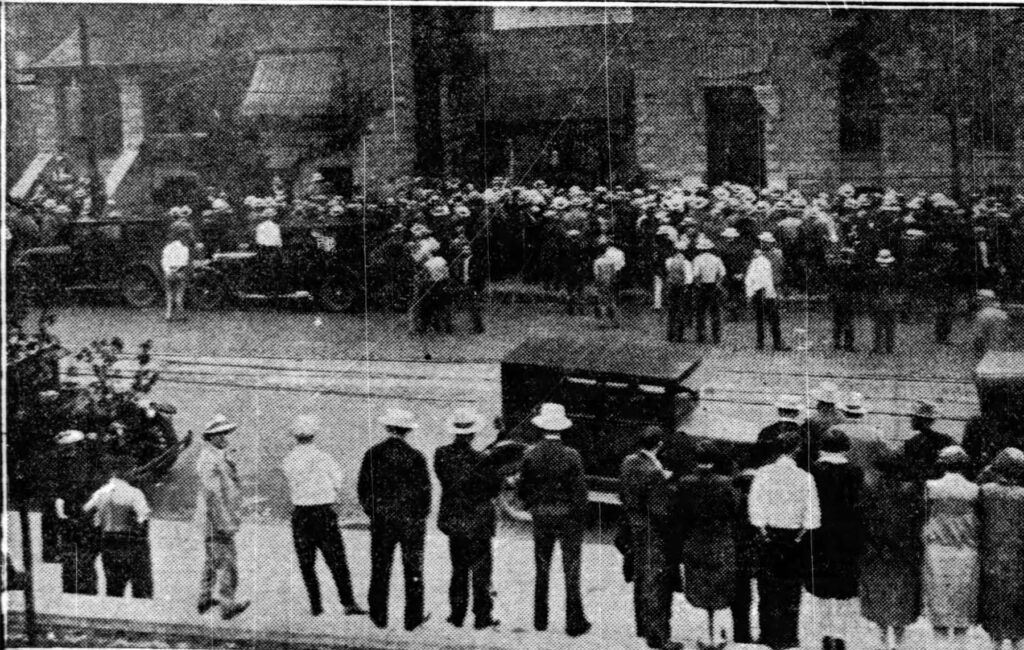

Finally in June 1924 Sheriff Clark arrested 26-year-old Jesse Mendoza in Brawley, an Imperial County town about 25 miles from the Mexican border. The sheriff revealed he had been tracking Mendoza after he heard the account of the two men buying gasoline in Moorpark late on the night of the murder. Mendoza was described as a “hophead” [morphine addict] and convicted forger. Clark and his deputies combed border towns in search of Mendoza. Whenever Mendoza felt he was being “shadowed,” he would disappear over the border. On three occasions, officers nearly captured him, but each time he evaded them by minutes and slipped back into Mexico. Twice, Clark identified places in Mexico where Mendoza was working but he continued to get away before he could be arrested. The break came when Clark received a tip that Mendoza was in Brawley. Clark and Deputy Sheriff Pablo Ayala rushed to the town. According to the Simi Valley Star, Mendoza was lured there “by the opportunity of meeting a woman of whom he was enamored.” Clark informed the Oxnard Press-Courier that “a second Mexican, the man who was with Mendoza is behind bars in the county jail.”

District Attorney Henderson joined Clark to question Mendoza. The Ventura Daily Post’s derisive description of Mendoza was that of a “fox-faced, olive skinned Mexican, with sharp shifting eyes.” He had grown a small mustache as a disguise. According to the Post, while at first denying his identity, Mendoza quickly made a complete confession saying he and a companion wanted Kahlly’s car. When Kahlly refused to loan it to them, a fight started resulting in his murder. Mendoza said Kahlly “fought hard for his life” but was no match for the two men.

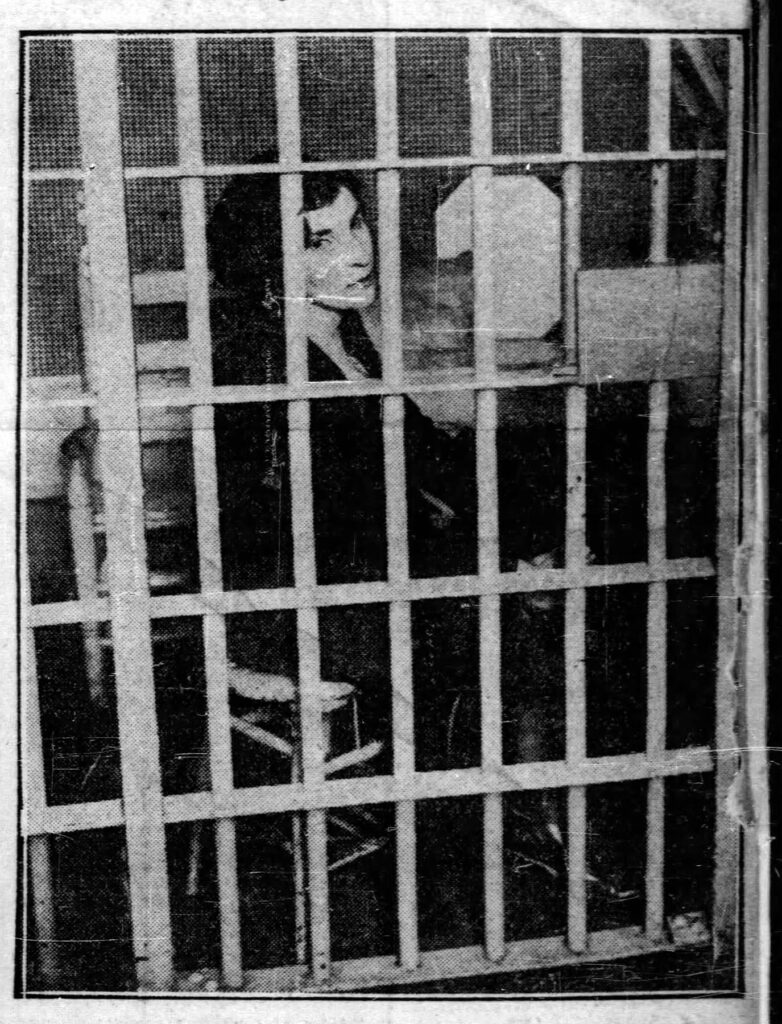

As the Sheriff and his party took Mendoza back to Ventura, they stopped in Moorpark where garage owner Mahan identified Mendoza as one of the two men who stopped for gas on the night of the murder. Once in county jail, the Ventura Daily Post reported Mendoza sat in his prison cell, “muttering to himself of the death cell at San Quentin.” The “morose, nervous and furtive” prisoner was startled by the opening and shutting of the jail cell doors. According to the Post, “Mendoza has not asked for an attorney. He does not want one. He is guilty, he says, and wants to get it over with as soon as possible.”

The Case Against Mendoza Takes Shape

A preliminary hearing was held July 10, 1924, before Judge Malvern Dimmick. District Attorney Henderson called several witnesses including Moorpark Southern Pacific Depot operator Walter Brown. Brown, a Quaker, refused to use the word “swear” in his oath when taking stand and insisted the word “affirm” be used instead. He testified that he helped two men shove their red Oldsmobile up the street to a garage after they had run out of gas.

Garage owner Mahan added some additional details in his testimony. He said he was suspicious of the two men. He said they “did not know where the oil went and neither of them knew much about driving the car.” Mahan said he wrote down the license number of the car, 79414, which matched the number on the car Kahlly was driving.

Oxnard constable Helmold identified the bloody rock and hammer handle found at the scene. Chinta, Kahlly’s friend for 15 years, described how he had identified the body. Chinta was the only witness cross-examined by Mendoza, who was acting in his own defense. Mendoza appeared “distinctly at ease” according to the Ventura Daily Post. He asked his questions in a calm, distinct voice. “A half smile flitted over his face” and he “seemed bored as well as amused” at Chinta’s responses to his questions. Mendoza’s parents had come from Riverside and saw the judge decide there was enough evidence to move ahead with a trial.

Newspaper Labels Spencer as a Modern Portia

Spencer appeared as pre-trial motions were heard in Superior Court. The “famous criminal attorney” had been retained by Mendoza’s father, Macario, and had come to Ventura the night before the hearing in response to his urgent telegram.

The Ventura Morning Free Press referred to Spencer as a “modern Portia.” Portia, a wealthy heiress in William Shakespeare’s play “The Merchant of Venice,” disguised herself as a male lawyer to help her favored suitor in a trial. She cleverly manipulates the outcome, showcasing her intelligence and resourcefulness. Spencer, who the Free Press referred to as “this strange counselor-at-law” surprised the court by not asking for a delay or continuance. Instead, she directed Mendoza to recant the confession he made to Sheriff Clark and District Attorney Henderson and enter a plea of not guilty. The trial was set for August 19th.

Shortly before Mendoza’s trial was begin, District Attorney Henderson revealed the second man wanted for Kahlly’s murder had been behind bars for months in San Quentin. Willie Vegas, who was sent to prison after a burglary conviction in Ventura, was brought back for a preliminary hearing before Judge Dimmick. Familiar witnesses such as garage owner Mahan, testified Vegas was one of the men who stopped for gas. Vegas’ attorney admitted his client was with Mendoza on the morning of the murder, but contended Mendoza picked him up late in the evening after Kahlly’s murder. Vegas’s attorney said Henderson had a weak case, and he called no witnesses to the stand. Judge Dimmick was not convinced, and Vegas was bound over to Superior Court to face trial for murder.

The names and cities of all 50 members of the jury pool were printed in the Ventura Weekly Post and Democrat. The prospective jurors came from Moorpark, Oxnard, Ventura, Santa Paula, Camarillo, Ojai, and Fillmore. They were all men. While suffrage had passed in California in 1911, it was not until 1917 that a woman served on a Ventura County jury, and they were still a rarity in 1924. As jury selection began on August 19th, every chair in the courtroom was filled. People came to see Spencer and she did not disappoint them. The Ventura Morning Free Press wrote that she “made a striking impressive figure in the somberness of the courtroom, being garbed in white.” In one day, she had nearly exhausted the entire jury pool, asking each prospective juror “whether he was prejudiced against the Mexican race, thought Mexicans inferior to Caucasians, or would doubt the veracity of a Mexican if placed upon the witness stand.” Spencer’s examination of each juror “was lengthy and in close detail and in most of them she traced their lives from youth to the present time.” The Free Press concluded, “one gets the impression that a witness might have a tendency to become quite nervous under the attack of questions and cross-examination.” The next day, an additional 35 prospective jurors were called to the courtroom and by 11:30 in the morning, the prosecution and defense agreed on the 12-member jury.

Trial Begins Amid Intense Public Interest

It was standing room only in the courtroom when the trial began after lunch as District Attorney Henderson and his assistant James C. Hollingsworth began presenting their case against Mendoza. Additional witnesses were called along with those who testified at the preliminary hearing. Rancher L. F. Deitrich testified that while driving to El Rio, he saw the maroon car with a black top “with two swarthy men, weighing about 135 to 140 pounds, standing by it.” He said that when he neared, they crouched as if seeking to conceal themselves.

Moorpark restaurant operator D. H. Ashey said Mendoza and companion came in around midnight and asked where they could get gasoline to take Mendoza’s mother to Los Angeles for an operation. Brown, the Quaker railroad dispatcher testified he was in Ashey’s restaurant. He said Mendoza and his companion asked him to help them push their car to Mahan’s garage. He said he somewhat reluctantly gave them a hand with the vehicle.

The prosecution presented its case quickly over two days, building a chain of mostly circumstantial evidence. Moorpark garage owner Mahan repeated his testimony from the preliminary hearing and added some new details. He said both men appeared nervous, neither had a hat or a coat. “While they claimed to be rushing their ill mother to Los Angeles,” Mahan testified, “I saw no woman in the car.” Dressed in a spotless white shirt, Mendoza watched every move in the courtroom and listened intently to the witnesses. During a break in the trial, he lit a cigarette and “smoked it thoughtfully.”

Spencer Cautioned by Judge After Outburst

The fireworks came when the prosecution called former undersheriff, then County Recorder R. N. Haydon. Haydon was present along with Sheriff Clark and District Attorney Henderson when Mendoza made his later-recanted confession in Brawley. Spencer fought the admission of Haydon’s testimony. Failing that, she was allowed by Judge Merle J. Rogers to put Mendoza on the stand to make a startling accusation. Mendoza said after his arrest, he was handcuffed and taken to a hotel room to be questioned. He insisted he told the officers, “Willie Vegas killed Kahlly.” He then claimed the men used the “third degree on him” to get his confession. When Haydon started his testimony, a clearly agitated Spencer interrupted him. The Oxnard Press-Courier reported that Spencer “stamped her foot and pounded on the court reporter’s desk” as she said, “I want to make a statement. You said, ‘You’d better talk and if you don’t then blood will come out of your nose.” Judge Rodgers immediately reprimanded Spencer, “There is no occasion to be vehement. Your statement of what happened, Mrs. Spencer, is not evidence. There are limits to which counsel may go and you will conduct this case in an orderly manner.” Haydon responded to the outburst and said, “I never stood over Mendoza and there was never such an occurrence and neither did anyone else in the room.” Haydon also denied Mendoza’s hands were cuffed during the interrogation, “One might have had a cuff, but I am positive that his two hands were not handcuffed.”

Spencer Introduces a Defense Based on a Diseased, Muddled Mind

Spencer began her defense on August 21st to save Mendoza from the gallows. Spencer’s challenge was not lost on the Ventura Morning Free Press as the newspaper suggested “an echo of the Loeb-Leopold trial at Chicago was heard in in the superior court room this morning.” Richard Loeb and Nathan Leopold confessed to the kidnap and murder of a 14-year-old boy for an “intellectual” thrill. Famed attorney Clarence Darrow conducted a defense based upon psychological testimony. His dramatic summation saved his clients from death and is still considered one of the most eloquent attacks on the death penalty in American legal history.

Spencer argued that Mendoza was so ravaged by a “malignant malady” that his mind was “muddled up.” Despite objections by the prosecution, Spencer brought witnesses to the stand who swore they had examined Mendoza, tested his blood, and found him to be “suffering from a malignant disease dreaded by the human race” since the age of 14.

Dr. Ross Moore, a well-known specialist in mental cases from Los Angeles testified that the disease would have a serious effect on Mendoza’s mental and physical condition. He said that, suffering from its ravages, Mendoza’s resistance would be greatly reduced.

While the “dreaded malignant disease” was never named in court, it most likely was syphilis. Despite public anti-venereal disease campaigns during World War I, syphilis carried a social stigma and was not openly discussed. There were no effective treatments, and the disease could invade the nervous system at any stage. Later stage syphilis could cause a wide range of symptoms including altered behavior, sensory deficit, and dementia.

Spencer’s argument to the jury was the “alleged confession” obtained from Mendoza was done through “rough methods” which forced him to concoct a tale in his muddled state of mind. The idea that a confession might have been beaten out of Mendoza came from an offhand remark made by Sheriff Clark. He was heard boasting in the court clerk’s office that he got confessions “by kicking prisoners in the shins.” In his testimony, Clark insisted that the remark was made in jest.

Mendoza’s New Story of the Night of the Murder

Spencer put Mendoza on the stand for his version of the events. He said he had worked for Kahlly and asked him for a ride to Santa Paula. As they were about to leave, Vegas came by and said he wanted to tag along to El Rio where he was going to see some girls he knew from Camarillo. Mendoza testified Kahlly “was intrigued” and wanted to wait with Vegas and meet the girls. They stopped at the alfalfa field between El Rio and Camarillo.

At this point, Mendoza’s story became unclear. He said Vegas and Kahlly were out of the car and started to fight. Vegas struck Kahlly several times with a hammer. Mendoza said he rushed to separate the two men, each of whom had a grip on the handle of the hammer. As he tried to take the hammer away from the men, it was pulled out of his hand and “accidentally struck Kahlly on the chin” with enough force to break the hammer head off the handle. The pair then dragged Kahlly over to the alfalfa patch as he moaned, “you’ll pay some day.” They propped Kahlly up against a tree. Mendoza said Vegas ran off, returned with the heavy rock, and delivered the fatal blow to Kahlly’s face. Vegas then “frisked” Kahlly’s pockets and gave Mendoza $5 for gas. He said Vegas threatened to kill him unless he got in the car and stayed with him during their escape. The Ventura County Star said Vegas appeared calm, “chewed gum” and showed little emotion during Mendoza’s testimony. The newspaper concluded he “seems to take the entire affair more as a theatrical exhibition than anything intimately connected with himself.”

Case Goes to the Jury on a Friday Night

Closing arguments were made on Friday afternoon, August 23rd. The Ventura Morning Free Press wrote that Spencer spent nearly two hours summarizing her insanity defense and pleaded with the jury to spare her client. Assistant District Attorney Hollingsworth was more succinct and according to the newspaper “made a very brilliant argument and is being complimented by attorneys and attendants at the trial.” The case went to the jury about 6 p.m. No one left the courtroom. Spencer sat with Mendoza as they waited for the jury to come in. After just five hours of deliberation, the jury came back with a verdict.

By the slimmest of margins, Mendoza had escaped the gallows. One juror, David Warner of the Ojai Valley was willing to vote for a conviction but was unwilling to see Mendoza hang. The other 11 jurors finally went along with life imprisonment rather than to have a hung jury and a mistrial.

Mendoza was sentenced by Judge Rogers the following Wednesday. With Spencer standing at Mendoza’s side, the judge sentenced him to life imprisonment. He told Mendoza, “This particular case is one of the brutal and diabolical murders in the history of the county, and after hearing the testimony in the case it may be said that the jury has been most generous with you.” Spencer announced she’d “better leave well enough alone” and smiled at the court audience as she said, “there will be no appeal.”

Spencer said, “Had I the trial to do over again I cannot see how I would change my tactics.” She was seen in the county for several days after the sentencing, the last time in Santa Paula where she said she planned to return to Chicago and would remain there for a couple of years before returning to California to make the state her home.

Two days after the sentencing, Sheriff Clark and a deputy took Mendoza to San Quentin. Vegas was soon to join him. District Attorney Henderson asked Judge Rogers to dismiss the murder charges against Vegas. Henderson said the cost of trying Vegas would not be justified as there did not appear to be sufficient evidence, other than Mendoza’s suspect testimony, to convict him. Vegas “smiled broadly” as he was led from the courtroom to be returned to prison to continue serving a five year to life sentence for burglary.

According to the San Francisco Examiner, Mendoza “passed beyond the control of prison regulations” when he died in San Quentin of tuberculosis on April 4, 1933.

Spencer’s Public and Private Life Remains in the Headlines

Spencer never returned to live in California. But her life in Chicago was frequently in the public spotlight. In 1925, she spent a night in jail after refusing to pay a $50 contempt of court fine. As she was led off to jail, Spencer announced, “Send for the newspaper photographers. I want my picture taken behind bars. I am pleased to go to jail. This fine will give me a thousand dollars’ worth of publicity.” Judge Charles A. Williams had warned Spencer “a score [20] of times” for her conduct in the trial of a Mexican man she was defending in a burglary case before he got fed up and held her in contempt. Once in the county jail, Spencer was put through “the same routine as other women prisoners.” She didn’t like the look of the jail dinner and reportedly gave a photographer a dollar with instructions to send up an order of ham and eggs. The next morning, her husband paid the $50 fine, and she was released. Spencer said, “Well thank God, I’m out. One night in a place like this is sufficient.” Meanwhile, the jurors who heard the burglary case issued a written resolution that commended the judge for punishing Spencer, “We feel that the judge was justified in upholding the dignity of court.”

In one of 1926’s most spectacular crimes, Spencer defended a Mexican man in a death penalty case. Robert Torres was one of six convicts accused of killing an assistant warden during a prison break at the new Stateville Prison near Chicago. Spencer, who opposed capital punishment, noted that never in the history of the state had six men been convicted of one murder. She and some of the other defense attorneys argued in vain that only two of the men had committed the actual murder, and the lives of the other convicts should be spared. But the evidence was overwhelming, and all six men were sentenced to hang.

Spencer and the other defense attorneys won an 11th hour stay of execution to bring the case before the Illinois Supreme Court. The court would ultimately grant three stays, delaying the execution until 1927. During the year-long delay, the desperate convicts made two escapes from the less-than-secure Joliet jail. Two of the inmates got away, one was shot dead, and the other men were recaptured. Torres did not attempt to leave his cell during the last jail break. At Joliet, a special, triple-trapped gallows had been built. Spencer and Luis Lupian, the Mexican counsel in Chicago, worked through the night trying to find a judge who would delay the execution while Torres’ sanity could be determined. They were unsuccessful and at dawn on July 15, 1927, the three men were hanged. The Chicago Tribune reported nearly 7,000 people walked through an undertaking room to view their bodies.

In 1933, Spencer joined forces with the mayor and police chief and attempted to stop Sally Rand, the actress turned burlesque dancer, from performing her “peek-a-boo” ostrich feather fan dance at the 1933 Chicago World’s Fair. After Rand was arrested four times in a single day, Spencer brought indecency charges against the dancer. Spencer, “looking very stern and regal” appeared with attorney Jay J. McCarthy, an expert on moral rules and regulations, before Judge Joseph David. They asked the court to compel Rand to perform fully clothed. Judge David wasn’t convinced. He said, “Some people would like to put pants on a horse. If nudity is such a crime, why doesn’t somebody put pants on the nymphs running around in the woods…if Sally Rand wants to go without them, it is alright with me.”

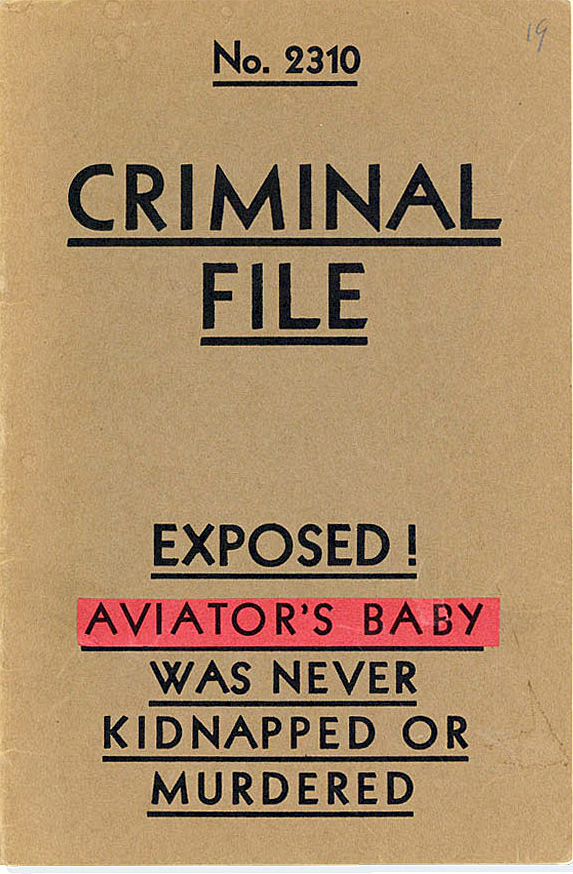

At the end of 1934, Spencer came under the eye of federal authorities as a jury was being empaneled for the “trial of the century” of German immigrant Bruno Hauptmann for the kidnapping and murder of aviator Charles Lindbergh’s 20-month-old son. Two years before the trial, Spencer had written an oddly prophetic pamphlet called No. 2310 Criminal File Exposed, Aviator’s Baby Was Never Kidnapped. The pamphlet describes the trial and acquittal of a “John Doe” and mentions a “Colonel Lindberg.” It was never determined who sent copies of Spencer’s pamphlet to each of the 150 prospective jurors in the Hauptmann trial. The state called it a “malicious and deliberate effort” to tamper with the jury. Spencer denied sending the pamphlet to the jurors. She said she wrote it as a satire “to poke fun at the asininity of our police and court system as a whole.” Spencer added, “I just took a bunch of fictional background from a dozen cases and wove them into something I thought was funny to expose the complete dumbness of the whole legal system.”

Spencer’s “Do-As-You-Please” Daughters

While Spencer’s court cases were often headline-grabbing, it was her child rearing style and her ongoing family dramas that drew the most public attention. The lawyer described as a “bulldog” in the courtroom had a surprisingly easy-going parenting style. She believed her daughters, Mary Belle and Victoria, were entitled to what the newspapers would describe as a “do-as-you-please” childhood. They were indulged, not neglected, and brought up “without repressions and inhibitions.”

The girls were home schooled. They roamed the hills in boy’s pants and boots, hunting and fishing while their “gingham-skirted” contemporaries were trapped in what Spencer saw as “germ laden” classrooms. She believed that “mass education enslaves people” and proudly boasted that “neither of my girls has ever been inside a classroom, yet they know everything. No one taught them to read or write or spell. They just learned.” Spencer added, “Before they could walk or talk, I used to read nursery rhymes and fairy tales to them, but they would just fall asleep. So, I shifted to the advance sheets of the supreme court, and they remained awake. For sheer enjoyment, though, they always preferred to have me read the records of the [Chicago] criminal court. Spencer insisted the girls thrived because she and her husband would never “bind their wings but let them grow up by inspiration” She compared them to butterflies, “My daughters awaken only after they have finished their sleep. Neither have they ever been told when they should go to bed. And they eat as inspirationally as they sleep. Neither of the girls has ever been ill. They’ve never had the mumps, the measles, any of the so-called children’s diseases. They’re the most powerful creatures you’ve ever seen.”

While newspaper editors found the exploits of the free-spirited girls to be a godsend, the Chicago School Board was less enamored. In 1935 they took Spencer’s husband before a magistrate for violating the compulsory education law by keeping his daughters out of school. In her best criminal-lawyer style, Spencer defended her husband for over two hours until interrupted by an annoyed judge who continued the case for a week. Ultimately, Dr. Spencer was ordered to pay a $5 fine. The couple then demanded a jury trial. The two children were their star witnesses. In court, little Mary Belle and Victoria looked like two “perfect ladies,” full of health and vitality and spoke with a vocabulary well above their age level. Daughter Mary Belle testified she received adequate home tutoring from her mother and a former high school teacher. This time, after the jury deliberated for eight hours, the Spencer method was vindicated.

Spencer once bragged, “My girls have never knuckled to anyone, not even their parents,” something she would learn in 1936 when her 16-year-old daughter Mary Belle ran off to Indiana to marry 21-year-old Edward Wright, a former high school football star. Spencer wanted to have the marriage annulled. She insisted her daughter was “only 16 and too young to know what it was all about.” Spencer ran into an unsympathetic judge and unbending Indiana law. She was told there was no way to annul a marriage that she was not a party to. Spencer then petitioned a Chicago court to annul the marriage on the grounds that Wright had untreated tuberculosis. In her suit, she claimed he “wickedly and feloniously” falsified his condition to Mary Belle and that he broke the law by taking a minor child across state line. But Spencer’s daughter was ready to “fight with every ounce of strength we have.” She added, “I don’t care if Mamma is a darn grand lawyer. If we have to, Edward and I will hire ourselves a lawyer that will protect us in our right to be together.” Ultimately Spencer decided to “let the annulment bill remain without action for the time being. I know Mary Belle so well that it won’t be necessary to proceed with it. She’ll want her freedom soon enough and she’ll go to court herself and ask for it.” She took one last poke at her estranged daughter, “It nauseates me to think of Mary Belle puttering around in that drab kitchen frying pork chops and getting grease in her beautiful auburn hair. It’s part of her growing pains – this marriage business. When she’s had her fill of it – and fried pork chops – she’ll be ready to return to her life’s work and use her mentality for something worthy of it.”

Spencer and her younger daughter Victoria also ended up in the headlines in 1938. Police were called to the Spencer home where they found Spencer holding 20-year-old Melvin Draben whom she had “shellacked” with a milk bottle and a hammer. When Draben brought 17-year-old Victoria home from a date at a tavern, she complained to her mother about his behavior. Spencer claimed Draben had “seized her wrists” when she asked him to leave. She said she swung the milk bottle and hammer in self-defense. Draben was arrested for disorderly conduct. He then pressed charges against Spencer. Cooler heads prevailed and within two weeks, both sides withdrew the charges against each other.

Turbulent Career Ends in a Quiet Death

The Chicago Daily News marked Spencer’s death on July 1, 1942, with the observation that the “turbulent career of Mary Belle Spencer has ended – in the quietness of death.” The newspaper added the “woman attorney who has been in and out of the news most of her life for scores of different reasons, died late yesterday in a hospital – St. Luke’s – an undramatic ending to a tempestuous life.” Spencer had been ill for several months but had continued to practice law from her Chicago office until five weeks before her death at age 59. She was living with her daughter Victoria in a Chicago suburb. Her other daughter, Mary Belle, her husband and three children lived in nearby Chicago Heights. Spencer’s husband died in 1938 after a heart attack.

Make History!

Support The Museum of Ventura County!

Membership

Join the Museum and you, your family, and guests will enjoy all the special benefits that make being a member of the Museum of Ventura County so worthwhile.

Support

Your donation will help support our online initiatives, keep exhibitions open and evolving, protect collections, and support education programs.

Bibliography

- “About Us.” Hindu American Foundation. Last modified September 18, 2022. https://www.hinduamerican.org/hinduphobia-history.

- American Bar Association. “ABA Profile of the Legal Profession – Lawyer Demographics.” Accessed April 7, 2024. https://www.abalegalprofile.com/demographics.html.

- “Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders in California.” United States Department of the Interior, National Parks Service. Accessed April 7, 2024. https://ohp.parks.ca.gov/pages/1054/files/CA_MultipleCounties_AsianAmericans-and-PacificIslanders-in-California%20MPS_MPDF_SLR.pdf.

- “The Association of the Bar of the City of New York – Women Lawyers.” Alexandra Kardaras Site. Accessed April 7, 2024. https://www2.nycbar.org/SLEOP/WomenChangingtheLawforWomen.htm.

- The Belleville News-Democrat (Belleville, Illinois). “Factional Fights in G.O.P. of Illinois.” April 11, 1922, 1.

- Bhandari, Shreya. “History of South Asians in the United States.” NASW Press. Accessed April 7, 2024. https://naswpress.org/FileCache/2024/02_February/South%20Asians%20in%20the%20United%20States-Sample%20Chapter.pdf.

- “California’s Women Lawyers: 134 Years and Counting.” Archived Issues. Accessed April 7, 2024. https://www.calbarjournal.com/March2012/TopHeadlines/TH4.aspx#:~:text=In%201920%2C%2072%20years%20after,associations%20in%20California%20were%20formed.

- Chicago Tribune. “4 Klein Killers Break Jail Third Time; One Slain.” June 14, 1927, 8.

- Chicago Tribune. “A Lawyer and Pioneer.” July 9, 2023, 14.

- Chicago Tribune. “Joliet Convicts, Awaiting Rope, Gain Freedom.” March 12, 1927, 2.

- Chicago Tribune. “Joliet Slayers Again Granted Hanging Stay.” March 9, 1927, 17.

- Chicago Tribune. “Mary B. Spencer, Former Public Guardian, Dies.” July 2, 1942, 25.

- Chicago Tribune. “Mary Belle and Daughter’s Suitor end Court Battle.” February 24, 1938, 3.

- Chicago Tribune. “Six Convicts to Die for Klien Murder.” November 27, 1926, 1.

- Chicago Tribune. “Spencerian Drama.” February 7, 1938, 7.

- Chicago Tribune. “Thousands View 3 Bodies After Joliet Hanging.” July 16, 1927, 5.

- Chicago Tribune. “Woman Glad to Enter Jail For Publicity of It.” April 30, 1925, 5.

- Chicago Tribune. “Woman Lawyer Glad She’s Out After Jail Night.” May 1, 1925, 19.

- Chicago Whip. “A Woman for Congress.” April 8, 1922, 6.

- Daily News (New York). “Sally Rand Find Courts Are Kind.” November 13, 1938, 18.

- Daily News (New York). “‘Problem Girl’ Defies Mama on Marriage.” August 28, 1936, 3.

- Daily Republican-Register (Mount Carmel, Illinois). “Inroads Made in Small Lines.” April 12, 1922, 1.

- Falck, Susan. Evolution of Ventura County Agriculture: 1782-2000. Ventura, CA: Ventura County Museum of History & Art., 2005.

- “The First Female Lawyer in California: Clara S. Foltz.” Contra Costa County Bar Association. Last modified March 17, 2021. https://www.cccba.org/article/the-first-female-lawyer-in-california-clara-s-foltz/.

- “Fox Movietone News Story 23-688.” Digital Collections – University of South Carolina Libraries. Accessed April 7, 2024. https://digital.tcl.sc.edu/digital/collection/MVTN/id/6888/.

- The Fresno Bee. “Hauptmann Jury Panel Tampering Attempt Charged.” December 24, 1934, 1.

- The Fresno Bee. “Rebuffed by Law.” August 25, 1936, 1.

- “Hint Arrest in Jury Tampering – Booklet Sent to Jury Panel (Mary Belle Spencer).” Newspapers.com. Last modified December 24, 1934. https://www.newspapers.com/article/the-kane-republican-hint-arrest-in-jury/133266637/.

- The Lake County Register (Libertyville, Illinois). “New Congresswoman Reared in Political Atmosphere at Capital.” November 15, 1922, 5.

- “The Legal Profession in the Early Twentieth Century.” De Gruyter. Last modified October 1, 2008. https://www.degruyter.com/document/doi/10.12987/9780300135022-004/html.

- “The Lindbergh Case.” Google Books. Accessed April 7, 2024. https://books.google.com/books?id=99gyrLNk8kwC&pg=PA274&lpg=PA274&dq=The+story+of+Mary+Belle+Spencer&source=bl&ots=8N666mzDct&sig=ACfU3U1sEfMxRWbyrOpswB5fpgSnqY7cPQ&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwjqhonh172EAxXAh-4BHYJIBR04KBDoAXoECAMQAw#v=onepage&q=The%20story%20of%20Mary%20Belle%20Spencer&f=false.

- Los Angeles Times. “Mother Beats Off Daughter’s Beau.” February 8, 1938, 2.

- Los Angeles Times. “Murder Mystery Solved.” June 23, 1924, 14.

- Morning Free Press (Ventura, CA). “Hundreds Hear Opening of Trial Ventura.” August 19, 1924, 1.

- Morning Free Press (Ventura, CA). “Jury Convicts Jess Mendoza, Recommends Life in Prison.” August 23, 1924, 1.

- Morning Free Press (Ventura, CA). “Jury Secured; Trial is Begun.” August 20, 1924, 1.

- Morning Free Press (Ventura, CA). “Little Items of News From This County.” September 15, 1924, 1.

- Morning Free Press (Ventura, CA). “Mendoza Murder Statement Result of Weakened Mind, Ruined By Disease, Claim.” August 21, 1924, 1.

- Morning Free Press (Ventura, CA). “Portia Comes to Defend Mendoza.” July 28, 1924, 1.

- Morning Free Press (Ventura, CA). “Seek Kahlly Car In Attempt to Solve Murder of Hindu.” November 3, 1923, 1.

- Morning Free Press (Ventura, CA). “Vegas Cleared of Kahlly Death.” September 4, 1924, 1.

- “Notes for Mary Belle Withrow.” Susan T. Miller’s Website – Thurtell and Related Families. Accessed April 7, 2024. https://www.thurtellfamily.net/geotf/gp/nti02600.html.

- Oakland Tribune. “Chicago’s Problem Child, 16, Elopes With Young Athlete.” August 24, 1936, 17.

- Oxnard Press-Courier. “Ashes of Hindoo to be Buried in Stockton.” November 14, 1923, 1.

- Oxnard Press-Courier. “Mendoza Guilty; Life in Prison is Recommended.” August 23, 1924, 1.

- Oxnard Press-Courier. “Murdered Hindoo Left No Money, Only Debts.” March 25, 1924, 1.

- Oxnard Press-Courier. “Sheriff Clark Nabs Murderer of S.T. Kahlly.” June 21, 1924, 1.

- Oxnard Press-Courier. “State Expected to Rest Its Case Today.” August 21, 1924, 1.

- Oxnard Press-Courier. “Two Mexicans Suspected of Hindoo Murder.” November 3, 1923, 1.

- Oxnard Press-Courier. “Woman, Noted Lawyer of Chicago to Defend Kahlly Murder Suspect.” July 29, 1924, 1.

- Oxnard Press-Courier. “Hindoo as Farmer Trying His Skill.” May 17, 1912, 3.

- “The Press: God & Baby.” TIME.com. Accessed April 7, 2024. https://content.time.com/time/subscriber/article/0,33009,847822,00.html.

- “Restriction of Immigration of Hindu Laborers.” University of Washington Libraries. Accessed April 7, 2024. https://www.lib.washington.edu/specialcollections/collections/exhibits/southasianstudents/docs/hindu-immigration-hearings-before-the-committee-on-immigration.-part-3.

- San Francisco Examiner. “Failed When She Wore Clothes – Succeeds when She Doesn’t.” September 24, 1933, 83.

- San Francisco Examiner. “Spare the Rod, Spoil the Child.” October 18, 1936, 97.

- Simi Valley Star. “Believe Hindoo’s Murderers Located.” November 15, 1923, 5.

- Simi Valley Star. “Dead Man’s Beneficiary Joins Hunt for Murderer.” December 20, 1923, 1.

- Simi Valley Star. “Local Man May Furnish Clue to Brutal Murder.” November 8, 1923, 5.

- Simi Valley Star. “Mendoza Preliminary.” July 10, 1924, 5.

- Simi Valley Star. “Murder Charge Filed Against Mendoza.” July 17, 1924, 1.

- Simi Valley Star. “Slayer of S. T. Kahlly Behind Bars.” June 26, 1924, 1.

- Simi Valley Star. “Willie Vegas Held On Murder Charge.” August 14, 1924, 4.

- Simi Vally Star. “Judge Call Woman Attorney to Order.” August 21, 1924, 5.

- “South Asian American, Punjabi Immigrants, South Asian Immigrants | Lesson Plan Curriculum | The Asian American Education Project.” The Asian American Education Project. Accessed April 7, 2024. https://asianamericanedu.org/early-south-asian-pioneers-in-california.html.

- “Spencer, Mary Belle.” AbeBooks | Shop for Books, Art & Collectibles. Accessed April 7, 2024. https://www.abebooks.com/book-search/author/spencer-mary-belle.

- “To Be White, Black, or Brown? South Asian Americans and the Race-Color Distinction.” Washington University in St. Louis Open Scholarship Repository. Accessed April 7, 2024. https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1548&context=law_globalstudies.

- Ventura County Star. “Judge Henderson, Lifelong County Resident, Dies at 92.” March 5, 1987, 2.

- Ventura County Star. “Remember Mary Belle? She Created a Sensation Here.” December 29, 1934, 1.

- Ventura Daily Post. “Attorney Mary Belle Off to See Governor.” August 28, 1924, 1.

- Ventura Daily Post. “Charge Vegas As Second Man In Murder Case.” August 13, 1924, 1.

- Ventura Daily Post. “City Briefs.” August 29, 1924, 3.

- Ventura Daily Post. “Defense of Mendoza is Started In Murder Case.” August 22, 1924, 1.

- Ventura Daily Post. “Jesse Mendoza Slayer of Former Wealthy Hindoo Under Arrest.” June 21, 1924, 1.

- Ventura Daily Post. “Lack of Evidence Causes Dismissal of Vegas Action.” September 5, 1924, 1.

- Ventura Daily Post. “Life in Prison Recommended by Jury in Case of Mendoza.” August 23, 1924, 1.

- Ventura Daily Post. “Mendoza Is Up For Preliminary.” July 9, 1924, 1.

- Ventura Daily Post. “Mendoza Repudiates Confession in Kahlly Murder to Not Guilty.” July 29, 1924, 1.

- Ventura Daily Post. “Mendoza Silent as Shadow of Noose Looms.” June 22, 1924, 1.

- Ventura Daily Post. “Mrs. Spencer Drops From Sight Leaving Her Baggage Here.” August 30, 1924, 1.

- Ventura Daily Post. “Special Venire of 35 Summoned in Murder Case.” August 20, 1924, 1.

- Ventura Daily Post. “Vegas Bound Over on Kahlly Murder Charge.” August 14, 1924, 1.

- Ventura Weekly Post and Democrat. “Identity of Two Murderers of Hindoo Land Boss is Made.” November 16, 1923, 1.

- Ventura Weekly Post and Democrat. “Kahlly Murderer Makes Confession.” June 27, 1924, 3.

- Ventura Weekly Post and Democrat. “Murderer of Hindoo May Be Arrested.” December 21, 1923, 4.

- Ventura Weekly Post and Democrat. “Venire Summoned in Murder Case.” August 15, 1924, 4.

- Ventura Weekly Post and Democrat. “Woman Lawyer Know Here is in Contempt.” May 8, 1925, 6.

- Walker, Elizabeth. “Her Daughters Never Went to School But “They Know Everything”.” The Californian (Salinas, CA), December 8, 1934, 7.

- “Women in the Legal Profession from the 1920s to the 1970s: What Can We Learn From Their Experience About Law and Social Change?” Scholarship@Cornell Law: A Digital Repository | Cornell University Law School Research. Accessed April 7, 2024. https://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1011&context=facpub.