By Library Volunteer Andy Ludlum

The frail old man, known to everyone in Simi as “Grandpa Stones,” practically had to be carried over the rugged ranch land. His friend, Bob Cannell stayed nearby in case he stumbled. Cannell had introduced Moroni Stones to rancher Tom Robertson, explaining that Stones was a local legend as a “water witch” and, for a $20 gold piece, he’d find water.

Robertson had just purchased the 512-acre Sinaloa Ranch, located in Simi Valley, and in the summer of 1925, he hired a driller to put in water wells along the eastern edge of his property. But the professional had only succeeded in drilling dry holes. Robertson, while subscribing to “sensible skepticism,” decided to give the water witch a chance, despite the driller’s protests.

Stones inched slowly over the ground with a little, Y-shaped peach branch in his hands. Suddenly, the tip of the branch dipped sharply, very close to where the driller had already put down a hole. When they dug at the spot, a “wonderful” artesian well bubbled up with a fine supply of water that supplied three farms for years. Robertson said, “We became firm believers in water witches!”

Water witching is centuries old. The first written references date to 16th century Europe. The dowser or “water witch” gently holds the end of a Y-shaped peach or willow branch (later bent metal wire) in his or her hands while carefully feeling for a downward tug that points to a good spot for a well. It was believed the rod, when held in skilled hands, would point towards underground water like the hands of a compass point towards magnetic north. John Steinbeck’s character Adam in East of Eden watched the action of a forked stick in the hands of a water witch. “He saw it quiver and then jerk a little, as though an invisible fish were tugging at a line.” The practice of dowsing was commonplace in the late 1800s in Simi Valley when new settlers needed to find a reliable source of water. Almost everyone gave it a try, but few had Grandpa Stones’ touch. Even into the 20th century, expensive, hired well drillers couldn’t offer any guarantee they’d find water.

Pico Arrives Among the First Colonists

The first Spanish settlers came to Simi Valley as part of a 240-person colonizing expedition led by Captain Juan Bautista de Anza in 1776. Among them was 43-year-old Santiago de la Cruz Pico. Pico spent his ten-year enlistment providing security at California presidios and missions. When he retired, he asked to settle permanently in Simi, but was denied. The government wanted to keep the old soldier close to the Pueblo of Los Angeles should he be needed as a peacekeeper. In 1795, Pico was finally given a concession, or permission to occupy the 113,000 acre El Rancho Simi. It was not an outright grant as the Spanish believed the land belonged to the King. The Picos raised sheep, cattle, and horses. Like the Chumash people who had been in the valley for thousands of years, the Picos relied on natural sources for their water, such as springs, streams, and rainfall. In the good years, rainfall produced adequate grasses to feed the livestock. During drought, they believed the rancho’s huge acreage would still provide enough feed for the animals. The family’s food supply was grown in gardens near the old ranch house which had year-round water from nearby Tapo Creek.

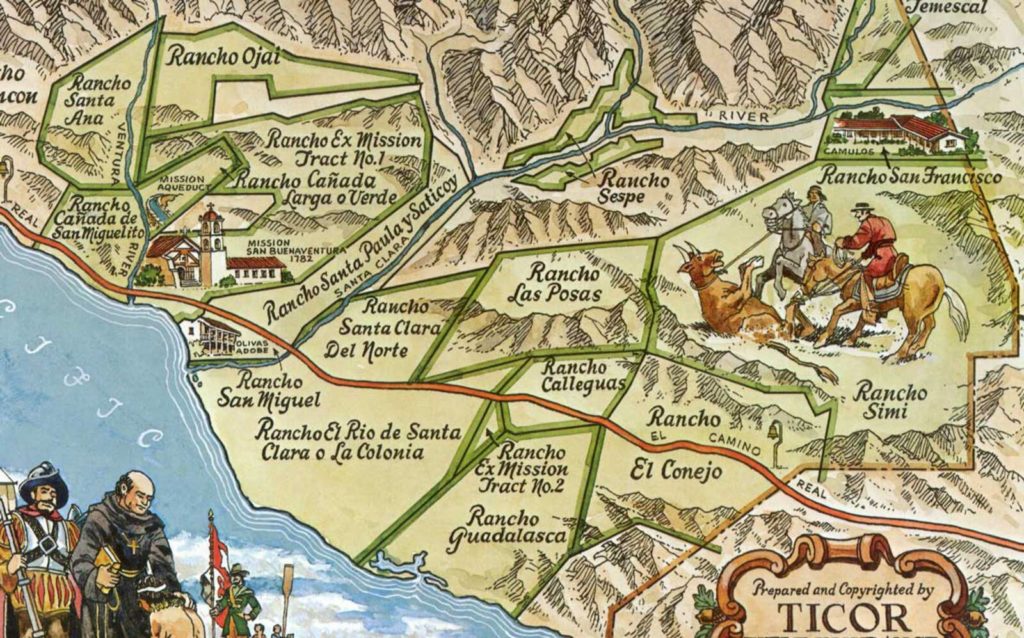

When Mexico won its independence in 1821, the rancho was no longer considered the property of the King of Spain. Pico had died, but title to the rancho was given to his three sons. Around 1832, the Picos sold the land to Don José De la Guerra y Noriega. Known as “El Capitán,” de la Guerra had been an officer in the Spanish army in Mexico for 52 years. For his loyal service, Don Jose was given several land grants, and eventually acquired a half a million acres of California land from San Luis Obispo to what is now the Los Angeles County line. It included several ranchos in Ventura County – Rancho Las Posas, Rancho Simi, and half of Rancho El Conejo.

After 27 years as part of Mexico, California was ceded to the United States in 1848 with the signing of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. Ten years later de la Guerra died, leaving his sons to operate the rancho. Like the Picos, the de la Guerras didn’t believe they needed additional water for their profitable cattle and sheep ranching. They dug a ditch to carry water from springs in the nearby hills to irrigate their vineyards at Rancho Simi. Ironically, it was lack of water that brought about the de la Guerra’s economic downfall. There was a drought from 1862 to 1864. It was so severe that the bodies of dead cows could be seen over the entire ranch. Debts from the failure of the ranching operation and bad management forced the de la Guerras to sell most of the rancho. The family kept the smaller, 14,000-acre Rancho Tapo.

Oil Speculators Buy Rancho Simi

In 1865, the Philadelphia and California Petroleum Company, a group of eastern oil speculators led by Thomas A. Scott, purchased Rancho Simi. Scott made his money investing in the Pennsylvania railroad during the Civil War. When the investors didn’t find any sign of oil, they decided to sell the land. Scott sent 27-year-old Thomas R. Bard to manage the properties. While attempting to sell the rancho, Bard leased land to a few ranchers.

Janet Scott Cameron, who served as a director of the Ventura County Historical Society in the 1960s, wrote that when the first prospective ranchers and farmers saw Simi Valley in the mid-1870s they “would have looked upon a valley whose virgin soil had as yet been unbroken for commercial purposes. No trees save…three or four old sycamores in the center; no fields of grain; not even a house was to be seen. Instead, sheep grazed on native grasses that grew abundantly, and drank from the waters of the Arroyo.”

The early farmers who rented land from Bard paid him one-sixth of their crops. It was a “gentleman’s agreement” with no signed leases. Like the cattle ranchers, the first farmers had little need for irrigation as they “dry farmed” barley and wheat and depended entirely on rainfall. That would change in the drought years.

Early Farmers Search for Water

During the dry year of 1877, on Rancho Las Posas west of Simi, farmer Peter Rice watched as vast fields of barley perished before his eyes. Rice thought he could save a field of corn situated on ground somewhat lower than the rest of the land. He picked a spot on the dry bed of Calleguas Creek and began drilling for water. At a depth of about 80 feet, he struck water. Within two weeks, he had three 7-inch artesian wells pouring water into a ditch leading to the corn field. The crop was saved. But water could only be made to flow on the low-lying parts of the ranch. Bard proposed the water be pumped, using a windmill, to a height of 160 feet where a reservoir could be constructed holding enough water to irrigate 6,000 acres. The Ventura Free Press concluded, “If Holland is kept pumped out by windmills there seems to be no good reason why ranches should not be irrigated in the same manner.”

Among the first ranchers to rent large areas from Scott was Charles Emerson Hoar. In 1872 he was offered Rancho Simi for $1 per acre. When his partners couldn’t come up with their share of the money, he leased 13,000-acres on the east end of the valley and moved into an adobe on the property that came to be known as Hummingbird’s Nest. Hoar eventually purchased the property along with several others in the valley. Ditches and pipes carried spring waters to the fruit orchards around his home. Hummingbird’s Nest became a show place for prospective buyers of land in Simi during the late-1880s.

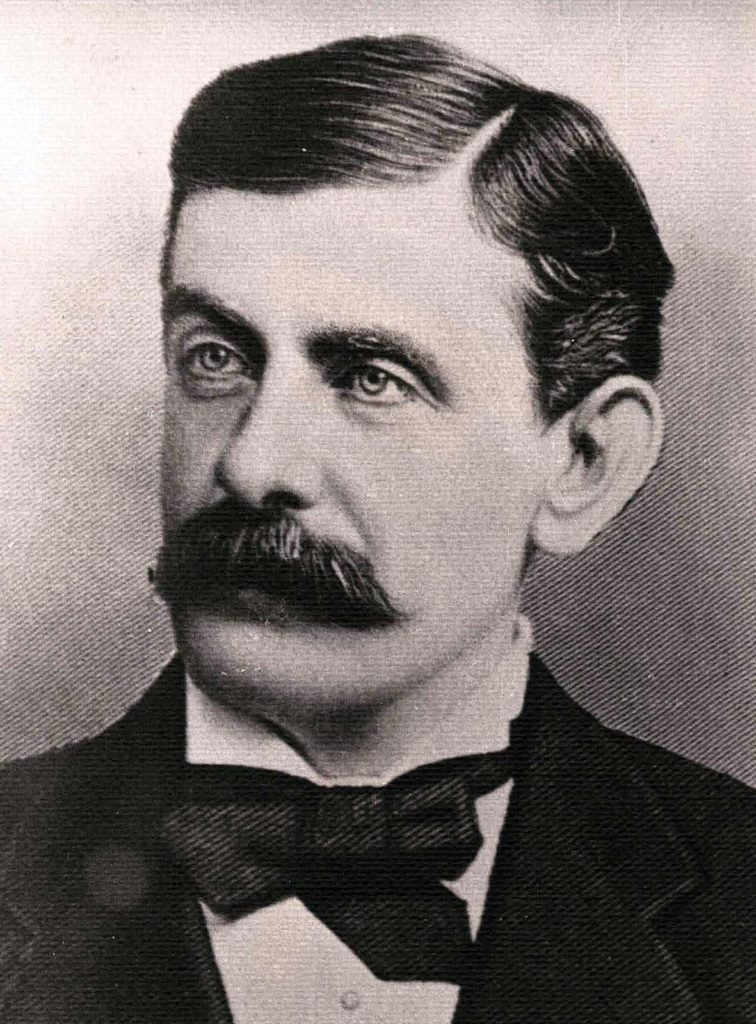

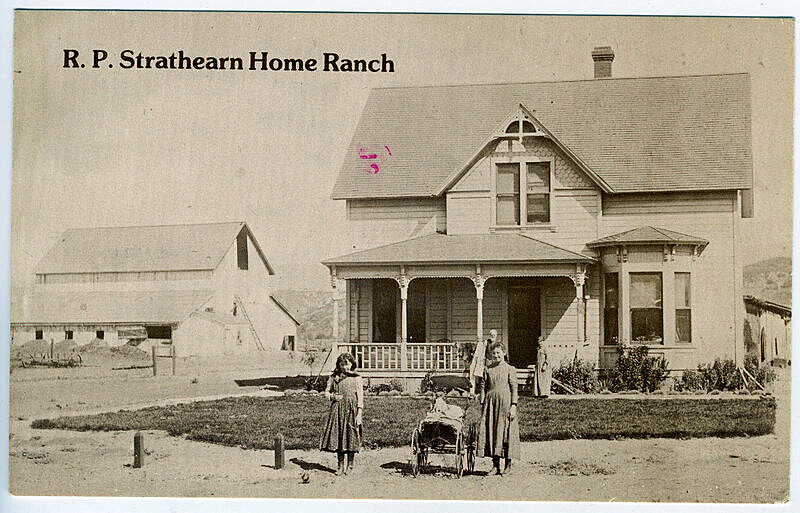

A Scot, Robert Strathearn bought 15,000 acres of Rancho Simi in 1889. Strathearn was a cattle rancher and introduced the first polled (hornless) Angus cattle to Southern California. The black cattle were particularly suited to the climate. In 1892 Strathearn built the front Victorian section of his house onto what remained of the old Simi Adobe. In 1969 the family donated the house and surrounding land to the Simi Valley Recreation and Park District to become the Robert P. Strathearn Historical Park.

Drought Forces the Old Don’s Heirs to Give Up Rancho Tapo

Meanwhile at Rancho Tapo, life at first was simple and pleasant for the de la Guerras. They loved to entertain. Guests would come on horseback from Ventura or Los Angeles for barbeques and dances. Sometimes the Simi farm families were invited to the festive events. Their house was protected from the heat by three-foot thick adobe walls and wide eaves on the roof. There was a ditch that brought water around the hillside from Tripas Canyon. The water irrigated an orchard surrounding the house with walnut, olive, pear, peach, pomegranate, and fig trees. It was drought again that caused the de la Guerras to lose their Tapo property. By the mid-1880s, Rancho Tapo was in mortgage foreclosure. In June 1885 a newspaper ad offered 14,400 acres of fine fruit land with “plenty of water” at $5 per acre.

Stones’ Long Route to Simi

Rancho Tapo was sold to Ventura merchant Abraham Bernheim and a Santa Barbara bank. This is when water witch Stones arrived in the valley. Stones recalled, “I moved to Simi in 1886 and leased part of the old De la Guerra homestead in the Tapo Canyon and lived in the old adobe house. It was in fair condition at the time.”

Stones was born in Missouri in 1847. He and his family crossed the plains by wagon and arrived in Salt Lake City in 1851. Later that year, the family became part of a Mormon colonizing group sent to San Bernardino. His niece, Cora May Bargmann, recalled in a 1976 interview, “Uncle Moroni had a good memory and was fond of expounding on events that had happened such as…their trials and tribulations crossing the country by wagon.”

At age 21, Stones left San Bernardino, moving to Utah and then Nevada. In Nevada, he married Clarissa Alger in 1870. In 1874 Stones and his wife (known by the nickname Lizzie) returned to San Bernardino and Los Angeles County before settling in Simi. Stones quickly became known as having “more than ordinary ability as a farmer as well as being a good mechanic.” His niece said, “He also had a thoughtful or inventive mind. He discovered that by squeezing eucalyptus leaves together one got relief from a cold, so he made up some eucalyptus oil. He passed this information on to all who would listen and someone with ingenuity has it processed. Uncle Moroni never got a cent for the idea.” The couple had four children, a son and three daughters. Bargmann describes her Aunt Lizzie as a good cook who loved her grandchildren. Lizzie, along with another local woman named Sara Willard served as midwives for the close-knit community. In their later years, Moroni and Lizzie become “honorary” grandparents to the entire community and were commonly known as Grandma and Grandpa Stones.

In March 1888, the Ventura Free Press wrote, “At Tapo may be seen some of the most beautiful places of California. With water in abundance, it has produced pear trees seven feet in circumference, almond trees with bark as smooth as willow twigs, grape vines thirty or forty years old, which are still bearing, and olives of the largest size and finest flavor. Last year Mr. Stones…concluded there was no use for irrigation and made no provision for it. The result was as large a crop of grapes, making as fine wine, as many olives and of as good flavor, and an immense crop of corn.”

Stones still managed the old vineyards and orchards and served as foreman of the ranch, now controlled by an English firm that raised horses. They hired cowboys to train the horses and to put on a show when visitors came to the valley. There was a racetrack in front of the old de la Guerra adobe and Stones would supervise horse races featuring the cowboys.

Simi Land and Water Company

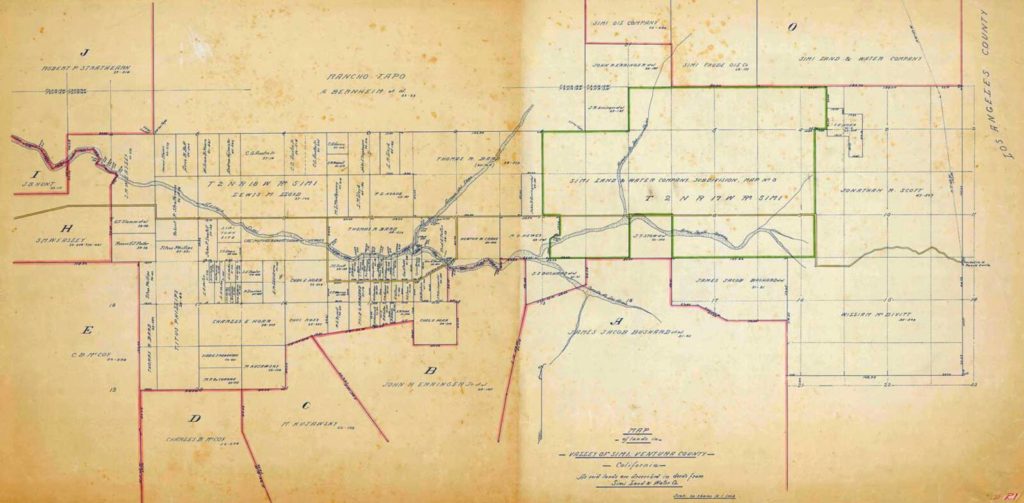

In 1887, Bard sold 96,000 acres to a group of Los Angeles businessmen who formed the Simi Land and Water Company. The company’s purpose was to carve the huge rancho into small farms and ranches and sell the property. Valley land was subdivided into small plots for farming. Hilly portions were cut into larger pieces and sold for cattle and sheep ranches. In 1888, the company built a hotel in the eastern end of the valley. Water from a nearby spring was brought to the hotel through a pipe. Ads touting the advantages of Simi with pictures of the newly built hotel appeared in Chicago and Cincinnati newspapers. The advertisement that attracted the most attention was one showing a man fishing in Simi Creek. It did not promise fish could be caught in the creek. The “fisherman” was sitting in his buggy throwing a line into the creek bed that did have a little running stream at the time.

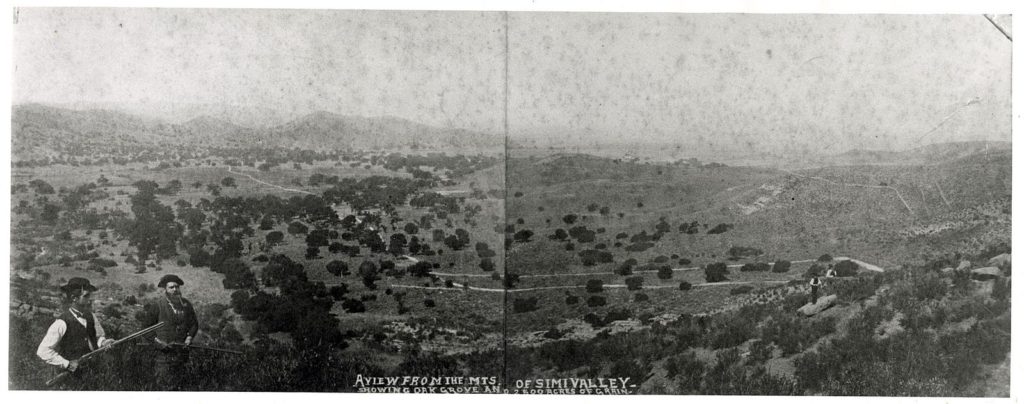

PN5852, Museum Library & Archives collection.

Charles B. McCoy was made the hotel’s resident manager. He ran stagecoach service between San Fernando and the hotel. The first artesian wells were drilled by the Simi Land and Water Company in the late 1880s. About 1917, the old Simi Hotel was dismantled, and the lumber was used to build more homes in Simi.

Three dry years in a row, 1898-1900, made it impossible for the farmers to continue to rely on rainfall. They needed a more dependable water supply to irrigate their crops and for household use. Stones had become established as a reliable finder of water. He had located and drilled artesian wells for many of the valley’s new farmers. Water was commonly found at depths from 50-80 feet and by 1895 each ranch house in the valley had an artesian well.

In October 1892, Stones gave the Ventura Free Press an account of all the wells he had put down. “On the town plot, a well 78 feet deep having a seven-inch pipe with three-inch overflow. J.A. Cutler’s 165 feet deep, water comes to the top. M. Stones, 37 feet deep, three-inch flow, eight feet above ground. Geo. Joslyn’s well 90 feet deep with a small flow over top. A.H. Davis’ 91 feet deep, two-inch flow, four feet above ground. Geo. Bott’s well, 100 feet deep, two-inch flow to the top. R. P. Strathearn’s well 60 feet deep, three-inch pipe, two-inch overflow. C.E. Hoar’s well, 90 feet deep, two-inch pipe, small flow above top.” The overflow measurement was how many inches over the top of the pipe water would flow, even without a pump, and indicated water pressure.

Chicago Investors Attempt to Form a Colony in Simi

The newspaper ads caught the attention of a group of Chicago doctors who formed a colonizing company called the California Mutual Benefit Colony of Chicago. The investors bought land and prepared to ship pre-cut lumber to be used to build houses for the new settlement. A group of colonists left Chicago on November 8, 1888, and arrived in San Fernando a week later.

As they rode the stage to Simi, some would-be settlers had second thoughts. The valley appeared to be one immense barley field. Along the foothills there was a dense growth of prickly pear cactus. There was no town, no buildings, no stores, and no conveniences. It was too much for some who gave up and started back for home, forfeiting their holdings to the company, which became known as the Colony.

But others were entranced by what would become their new home. C.G. Austin kept a diary in which he wrote, “The Simi Hotel where we are to stop is a fine-looking building built upon a hill…we found it pleasant. Water is furnished by pipes running up into the mountains and fed there by a mountain stream. We find Mr. McCoy one of the most genial and accommodating landlords.”

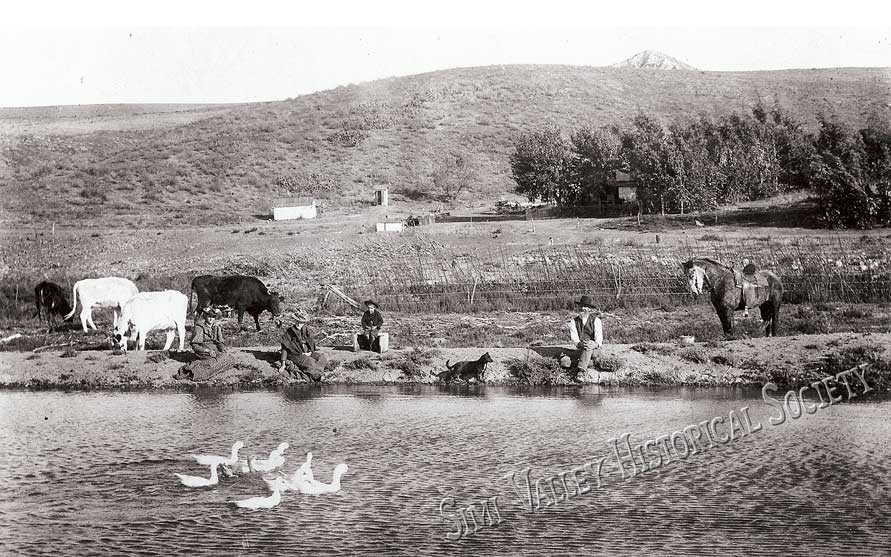

PN2327, Museum Library & Archives collection.

“Through the valley runs a creek called here, Arroyo. At this time its bed for about halfway through the valley is dry. Farther on water seeps out of the ground and by the time it reaches the colony ground it contains a nice stream of seemingly good water.” Austin raved about the two artesian wells, gushing water several feet high, that the Simi Land and Water Company had sunk in the valley.

Colony members could buy their “kit” houses for about $300 and have them shipped by rail from Chicago. As an incentive, the Colony said it would pay the freight expenses for the first 15 houses. Only 12 of these houses were shipped to Saticoy and then hauled to Simi by horse-drawn wagon. There they were to be assembled in the Colony’s town site. The colonists lived in tents while their houses were being built. There were no carpenters in their group, so work proceeded slowly. Stones and other ranchers living in the valley welcomed and helped the newcomers.

All but two of the Colony houses were built on the town site, which was called Simiopolis for a little over six months until it was shortened to Simi. Water for the Colony houses came from artesian wells. Because of strong groundwater pressure, these wells could push water to the second floor of the homes.

The Colony Dream is Crushed by Debt

The Colony began to develop serious financial problems. Many of the original investors bailed. Owners were levied a special assessment to pay past-due interest on loans. Homeowners were now told they were expected to reimburse the $35 “advanced by the colony” to ship the houses from Chicago. The financial problems only worsened and in 1891 the Colony made a deal with the Simi Land and Water Company to give up all their interests in Simi land. Colonists were given credit for what they had paid and were allowed to keep their houses. The Simi Land and Water Company disposed of those parts which it still held and passed out of existence. Stones and his wife eventually moved into one of the Colony houses facing First Street. That house stood until the 1950s.

The small farmers in the newly sub-divided valley with their orchard planting and water dependent crops had a growing demand for water. By the early 1900s hand pumps and hand dug wells with windmills dotted the valley. In 1904 the Ventura Free Press reported, “Several (water) pumping plants are being started in the valley preparatory to irrigating the crops. I.T. Barnes and F.J. Fitzgerald have already installed plants on their premises and L.M. Lloyd is preparing to put a big plant soon on his ranch. Should irrigation become effective here this valley will blossom as the rose and will rival in beauty and fertility of soil” any part of southern California.

The Water Witch Becomes a Beloved Community Fixture

While water witching is never mentioned, Stones’ activities were regularly reported in the newspapers. It was front page news in the Oxnard Courier in September 1911 when Stones “struck a good flow at about 100 feet” on the property of Ida Kreisher. The article added, “Now Mrs. Kreisher has a good artesian well that flows an inch above a three-inch casing.” Similar articles are written for wells that Stones drilled for Joe Jaques, Frank Pitts, Joe Alger, and George Willard.

Willard’s daughter Elaine recalled in Patricia Havens’ book, Simi Valley, A Journey Through Time, “Everyone had a well “witched’ before drilling. Grandpa (Moroni) Stones was the most noted ‘witcher’ but everyone tried it. Mother tried, thinking it was a bunch of hooey. The willow crotch didn’t do anything in her hands, but when Grandpa Stones walked behind her and put his hands over hers, she peeled the switch of willow trying to keep it from going down (responding).”

Gerald Haigh in his memoir, Straw Roads, described water as,

[P]lentiful in Simi when I was a young boy, supplies from artesian wells. We boys had no radio or T.V. sets, but one thing we did have was a fine old couple living in one of the Colony houses, Grandma and Grandpa Stones. They were the kindest people in the world. We would gather around the kitchen stove after supper and Grandpa would read stories to us. Some stories I still remember were “Riders of the Purple Sage” and “Untamed.” Stories read with such feeling we could see the characters; we could close our eyes and re-live those days of the rugged West. To amuse himself, Grandpa would wait until we were all seated, then he would reach up on a shelf and get a book that had been closed the night before at a very exciting part; he would lay the book down on a little stand near his rocking chair in front of the stove. Then he would roll a Bull Durham cigarette. Then he would fumble around in his pocket for a match. After lighting the cigarette, we thought we were under way. But no. He took the lid off the stove and put in another stick of wood. All this time we could see a gleam of mischief in his eyes.

Water Witching Relied More on Faith Than Science

In 1907 the Oxnard Courier touted the “abundance of water at moderate expense” in Simi Valley. Wells could be sunk for only $1 per foot and could “tap a current of water that would flow over the top all the year round, seldom fluctuating.” The newspaper optimistically concluded, “The fact that this water never gives out even in a dry season is the great secret of the success that attends all agricultural industries in this valley.” Later in the 20th century, demand stressed and depleted the ground water supply.

In 1988, water witch Riley Spencer demonstrated the water finding technique in a television interview for the Saticoy Historical Society. Using a peach limb he noted, “When you get close to the water it’ll go straight down, see?” The limb moved with enough force to snap and sting Spencer’s hand.

While Stones was clearly successful, even legendary, in finding and drilling artesian wells during his years in Simi Valley, when water witching is exposed to scientific scrutiny, it doesn’t hold up. The U.S. Geological Survey noted in many areas “underground water is so prevalent close to the land surface that it would be hard to drill a well and not find water.” The National Ground Water Association claimed that more than 90 percent of the earth’s surface has water within a drillable depth.

Magician turned debunker, James Randi, offered a $1 million prize to anyone who can scientifically prove they have paranormal abilities. “The Amazing” Randi said of the hundreds of dowsers tested, none could demonstrate results that were any better than chance.

After being confined to bed for several months, “Grandpa” Stones passed away at the age of 83 on December 20, 1930. His wife Lizzie had died two years earlier. Moorpark’s Community Church was filled with flowers and packed with his many friends. The Stones were buried at Simi Cemetery.

Make History!

Support The Museum of Ventura County!

Membership

Join the Museum and you, your family, and guests will enjoy all the special benefits that make being a member of the Museum of Ventura County so worthwhile.

Support

Your donation will help support our online initiatives, keep exhibitions open and evolving, protect collections, and support education programs.

Bibliography

- Appleton, Bill, and Simi Valley Historical Society. Santa Susana. Charleston: Arcadia Publishing, 2009.

- Cameron, Janet S. “Early Days in the Simi Valley.” The Ventura County Historical Society Quarterly 13, no. 1 (November 1967), 3-10.

- Cameron, Janet S. “Early Transportation in Southeastern Ventura County.” The Ventura County Historical Society Quarterly 10, no. 1 (November 1964), 14.

- Cameron, Janet S. “The California Mutual Benefit Colony of Chicago.” The Ventura County Historical Society Quarterly 3, no. 4 (August 1958), 1-13.

- “Dowsing: Real Deal or Too Much Zeal?” The Salt Lake Tribune. Accessed March 16, 2022. https://archive.sltrib.com/story.php?ref=/business/ci_2959255.

- “Early Days on the Simi.” Simi Trail Blazers – Simi Trail Blazers. Last modified October 2006. https://www.simitrailblazers.com/newsletters/10-06.pdf.

- “George Isreal Willard.” Find a Grave – Millions of Cemetery Records. Accessed March 16, 2022. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/73720151/george-isreal-willard.

- Haigh, Gerald. Straw Roads: A Story of Simi Valley from 1908 to 1960, Ventura County, California. Simi Valley: Simi Valley Historical Society, 1975.

- Havens, Patricia. On the Tapo: Simi Valley’s Finest Agricultural Development. Simi Valley: Simi Valley Historical Society & Museum, 2021.

- Havens, Patricia, and Simi Valley Historical Society and Museum. Simi Valley: A Journey Through Time. Simi Valley: Simi Valley Historical Society & Museum, 1997.

- “Henry Moroni Stones.” Find a Grave – Millions of Cemetery Records. Accessed March 16, 2022. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/109500726/henry-moroni-stones.

- “Last of Simiopolis.” Daily News. Last modified August 29, 2017. https://www.dailynews.com/2005/11/13/last-of-simiopolis/.

- Miller, Crane S. “The Changing Agricultural Landscape of the Simi Valley From 1795 to 1960.” The Ventura County Historical Society Quarterly 13, no. 4 (August 1968), 20.

- Moorpark Enterprise. “Simi Pioneer Passes Away at Burbank.” December 25, 1930.

- Oxnard Courier. “Good Flow of Water Struck in Simi Valley Well.” September 8, 1911, 1.

- Oxnard Courier. “Memorial Day Services Held at Simi Church.” June 15, 1911, 4.

- Oxnard Courier. “Simi People Have a Week of Many Happenings.” October 2, 1911, 8.

- Oxnard Courier. “Simi Preparing For Its First Institute.” September 29, 1911, 5.

- Oxnard Courier. “Simi Woman’s Club Holds Meeting Oct. 26.” November 2, 1911, 1.

- Saticoy Historical Society. “Interview of Riley Spencer.” 1988.

- Sheridan, Ed M. “Woman Tells Colonization of the Great Simi Valley.” Ventura County Star, April 9, 1929.

- “Simiopolis.” Strathearn Historical Park and Museum. Accessed March 16, 2022. https://www.simihistory.com/portfolio-items/simiopolis/.

- Steinbeck, John. East of Eden. London: Penguin, 2003.

- “Strathearn House.” Strathearn Historical Park and Museum. Accessed March 16, 2022. https://www.simihistory.com/portfolio-items/strathearn-house/.

- Ventura Free Press. “Jottings From Old Jeff.” November 30, 1878, 3.

- Ventura Free Press. “Simi Simmerings.” October 21, 1892, 5.

- Ventura Free Press. “Simi.” May 20, 1904, 6.

- Ventura Free Press. “What May Be Seen?” March 30, 1888, 3.

- “Water Witching.” Wheat & Tares. Last modified October 16, 2021. https://wheatandtares.org/2021/10/17/water-witching/.

- “Water.” The Ventura County Historical Society Quarterly 5, no. 4 (August 1960), 1.