by Library Docent Volunteer Andy Ludlum

At first glance, the picture is nothing special. It’s a group of 31 men, posed in front of the Ventura Mill & Lumber Company. They are all dressed in their best clothing, suits and hats, most wearing ties. What makes the picture historic is that it was taken on Easter Sunday, the morning of April 8, 1917, two days after the United States had declared war on Germany. The young Ventura men had all volunteered to serve their country as members of a state naval militia. Newspaperman, author, and curator of what would become the Museum of Ventura County, E. M. Sheridan wrote that the photograph finally told the “little sleepy mission town” that “there really was a war and their own land was into it.”

Prelude to War

For most Venturans, the war in Europe was a world away. In 1914, Russia, France, and Great Britian formed an alliance against Germany, Austria-Hungary, and Turkey. The four-year conflict would also embroil Italy, Japan, parts of the Middle East, and ultimately the United States.

Prior to 1917, the United States was officially neutral, though American organizations and private individuals were involved in fund raising, aid efforts, volunteerism, and even combat.

Tensions built between the United States and Germany over attacks on passenger and merchant ships. On May 7, 1915, a German submarine torpedoed and sank the Lusitania, a British cruise liner traveling from New York to Liverpool. There were 123 Americans among the 1,195 men, women and children who died in the attack.

Almost a year later, U-boats fired torpedoes at an unarmed French boat, the Sussex. The Germans contended the civilian ferry was a military craft laying mines to destroy German ships. The Sussex didn’t sink but arrived in port heavily damaged. Eighty people died including two Americans.

President Woodrow Wilson threatened to sever diplomatic relations with Germany unless they pledged to refrain from attacking all passenger ships. Germany agreed to the conditions. But eight months later, in January 1917, the German Navy convinced Kaiser Wilhelm II that the resumption of unrestricted submarine warfare could help defeat Great Britian within five months. As for the pledge, German military leadership insisted the United States could no longer be considered neutral after supplying financial assistance to the Allies and not objecting to an Allied blockade of Germany.

In April, President Wilson denounced Germany’s renewed submarine attacks as “a war against mankind. It is a war against all nations.” He also spoke about the treachery of an intercepted coded telegram sent by German Foreign Secretary Arthur Zimmermann enticing neutral Mexico to declare war on the United States. The telegram suggested Germany would give Mexico “general financial support, and it is understood that Mexico is to reconquer the lost provinces in New Mexico, Texas and Arizona.” The Zimmerman telegram reached Mexican President Venustiano Carranza, but it was officially rejected once a military commission determined that there would be no benefit in pursuing the offer. The Ventura Weekly Post and Democrat wasn’t at all charitable with Carrenza, accusing him of actively negotiating with the Germans. The editors concluded, “Mexico’s treachery is established. Carranza’s activities are limited only by his impotence.” President Wilson asked Congress for a declaration of war against Germany and the United States officially entered the conflict on April 6, 1917.

Naval Militias

At the end of the Civil War, the United States Navy was too large and too expensive for peacetime. By 1871 the Navy had shrunk from 671 ships and 51,000 enlisted men to 52 ships and 8,500 sailors. To be prepared for future needs, Congress directed the Navy to organize a reserve force or a system of state naval militias. States were offered financial incentives. California formed its first naval militia in 1891.

The Navy Department started the practice of allowing state militia members to drill aboard Navy ships. By 1894, five states, including California, trained on decommissioned ships lent to them by the Navy. But these loaners were the worst that the Navy had. Many of the ships were even condemned. Militias found it difficult to conduct proper drills and exercises on ships unsuitable for naval purposes. A more fundamental problem with the militias was they were state run and not under federal control. Properly run state militias showed high levels of readiness. But poorly run, underfunded militias failed inspections, and their sailors performed badly aboard regular Navy ships during summer training cruises.

As World War I was beginning in Europe, the Naval Militia Act of 1914 made it possible for the President, as commander in chief of the armed forces, to call out the naval militias when either a national emergency or a state of war existed.

The United States now had the world’s second largest navy, only Great Britain’s Royal Navy was larger. Even as U.S. involvement in the war appeared imminent, the Navy was still reluctant to allow the state militias to operate the warships it held in reserve for possible hostilities. Assistant Secretary of the Navy, Franklin D. Roosevelt would not give up the ships as “it would materially weaken our force of destroyers available for war purposes.” One congressman from South Carolina sniped at Roosevelt, “As I understand it, you want to encourage these naval militia men, but do not want to give them anything to practice on.”

The day the United States entered the war, Secretary of the Navy Josephus Daniels called the state naval militias into federal service as National Naval Volunteers. By September, 852 officers and 16,000 enlisted men had entered federal service. Over the next year, an overwhelming majority of militia men saw some form of service in the regular Navy.

Recruitment and Turnout

The first mention of forming a naval militia in Ventura was on March 23, 1917, when the son of an oil tycoon, Los Angeles businessman Edward L. Doheny Jr. came to Ventura. With local man, C.W. Smith, Doheny called on local business leaders to gauge interest in forming a naval militia.

A week later, the large courtroom at the Ventura County Courthouse was packed as young men listened to an appeal to enlist in the naval militia. Attendees at the rousing, patriotic gathering were thrilled as Civil War veteran W.E. Shepherd regaled them with stories of his days in the Union Army’s Third Iowa infantry. The 75-year-old retired lawyer knew how to tell a story; he’d been the editor of the Ventura Signal for six years in the 1870’s. A militia captain pitched the young men on the advantages of the Navy over the Army. The men were assured if enough of them signed up, a section and even a division of the militia would be organized in Ventura. Ralph Oberg, an employee of Fazio & Newby’s grocery store on Main Street was the first young man to answer the call. Fourteen other men committed that night including Charles P. Daly and the local organizer Smith. Almost two dozen more men indicated they were considering enlistment. The Ventura Morning Free Press concluded, “If war is declared someday this city and its people will look back to this memorable meeting at the courthouse when the first patriotic slogan was sounded, and when a dozen or more of her young men responded to the call for enlistment in the naval militia.”

Shepherd, Smith and Daly continued to recruit more young men to sign up for the militia. With less than two dozen assured, they were short of the 60 men needed to form a full company with Ventura as its headquarters. Community leaders wanted a company “independent from any other county” and chafed at the idea of “their boys” being used to complete the Santa Barbara contingent.

At another large, enthusiastic meeting of mostly young men at the courthouse on April 3, attendees were urged to come forward and sign up for the militia to prove “that the provocation which has led up to the crisis is such that every red-blooded American is in hearty sympathy with the action of the American government.” At the meeting Daly introduced a resolution supporting “the President of the United States in declaring that the acts of Germany have been such as to constitute actual war and in declaring that we will not choose the path of submission and suffer the most sacred rights of our nation and our people to be ignored or violated.” Daly’s family grocery store was designated as the place where recruits could get more information or sign up.

The Morning Free Press reported 41 men had “enrolled to signify their willingness to fight for their country if need be.” The names of more of the city’s sons appeared on the list including Waldo Dingman Jr., the son of Ventura photographer Waldo Henry Dingman who took the Easter Sunday photo of the first volunteers. The Ventura County Board of Supervisors passed a resolution promising county employees who enlisted that they would get their jobs back when they returned. The Merchants’ Association passed a similar resolution. Grocer Fazio & Newby Co. promised “any of the young men in our employ who enlist and who serve in army or navy will be given back their positions when they return to Ventura.”

Once the United States entered the war, Secretary of the Navy Josephus Daniels ordered the Navy to mobilize. This included putting all ships in commission and calling the naval reserves and the naval militia to federal service.

The next evening the Ventura volunteers were given the oath of office and were told their company had been assigned to the new Eleventh division of Los Angeles, instead of being part of the Santa Barbara contingent. Their orders were to board the train to Los Angeles the next morning. The Morning Free Press reported there was a “large throng at the Southern Pacific station Sunday as the Ventura boys left for the city and many weeping mothers and fathers as well made the scene a memorable one. Three rousing cheers for the boys were given as the train pulled out.”

In Los Angeles, the young men underwent physical examinations. Eighteen of the 30 young men passed, including Daly and Dingman. For boys under 21, parental consent had to be given. The Morning Free Press noted that “telephone messages were hot between headquarters and parents” and in all but one case parental permission was granted. Harold Oberg, the first Venturan to sign up for the militia, was rejected because of poor eyesight. He returned to Ventura and his old job with Fazio & Newby. While others also returned home, some stayed in Los Angeles to look for wartime service.

Daly and Smith both received commissions in the naval militia. Smith was commissioned as a first lieutenant and Daly as a second yeoman. Emmett Ammons, who the Morning Free Press described as a “popular youngster” was named a boatswain’s mate.

During the short stay in Los Angeles, some family members were allowed to visit the volunteers. Details of their trips were eagerly printed by the newspapers. Photographer W. H. Dingman and his wife made a day trip to the naval camp at Exposition Park. They described the Ventura boys as “all enthusiastic and happy and all doing well.” Before the end of April, the Ventura men who enlisted in the naval militia would find themselves aboard the U.S.S. St. Louis.

The U.S.S. St. Louis

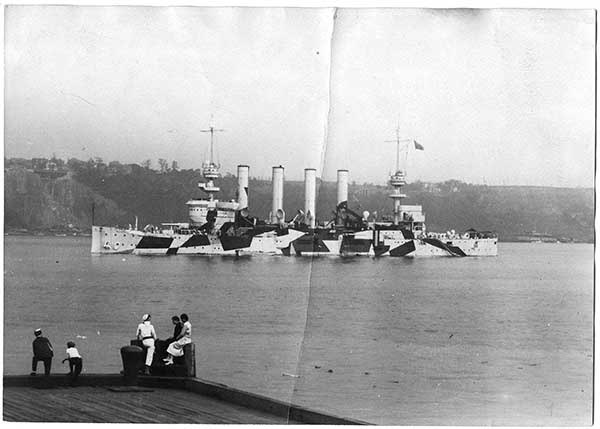

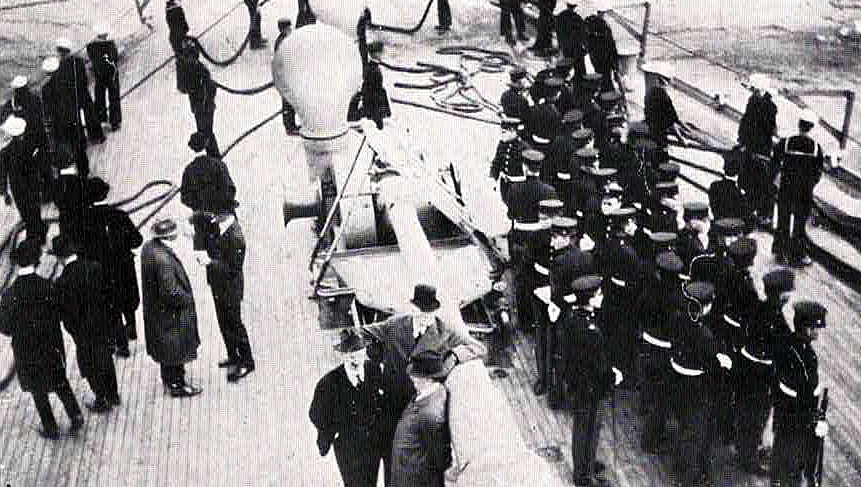

Within 72 hours after war was declared, the U.S.S. St. Louis left her peace time port of Honolulu on April 9, 1917, bound for San Diego. In San Diego, she took on board 517 National Naval Volunteers, including the men from Ventura. On April 20, with a full crew, she was placed in full commission.

The 426 foot long, 9,700-ton St. Louis was a “protected cruiser,” part of a class of smaller, faster warships that, due to recent improvements in technology, had strong armament protecting her hull and deck.

Named in honor of the city of St. Louis, Missouri, the mayor, Rolla Wells was pressured by local brewers to christen the ship with a bottle of the city’s famous beer instead of the customary champagne. Wells resisted the pressure and a student from the Mary Institute, a private school for girls, christened the ship with champagne on May 6, 1905. In and out of active and reserve service, the St. Louis had assignments in South and Central America, as part of the Pacific Reserve Fleet based in Washington’s Puget Sound, and eventually in Hawaii.

Wartime Service Aboard the St. Louis

In June 1917 the St. Louis was assigned to escort troop and supply ships as part of the first convoy of General John J. Pershing’s American Expeditionary Forces to the Naval Operating Base at St. Nazaire, France. According to the War Log of the U.S.S. St. Louis, given to the Museum of Ventura County by Daly’s widow, much of the 12-day voyage was spent watching and waiting. The St. Louis opened fire when a lookout cried, “Periscope abaft the starboard beam!” When the St. Louis stopped firing, the intruder had slipped away. Two days later, a torpedo passed within 50 yards of another ship in the convoy and only missed because the captain took evasive action. The St. Louis fired one more time when a periscope was spotted on July 1st. Later that day, the convoy made it to St. Nazaire harbor and the first American soldiers set foot on French soil.

In October 1917 she made her way through perilous mine-laden waters and evaded submarines on a secret mission to carry members of the high-level commission led by Colonel Edward M. House to confer with European allies. House was a trusted emissary to President Wilson and helped coordinate the American war effort with the Allies. The Commission’s mission was withheld from the press until the column of ships made their final dash through the danger zone and cruised up the English Channel. House was Wilson’s chief negotiator in Europe and would ultimately be successful in persuading European powers to agree to an armistice in November 1918.

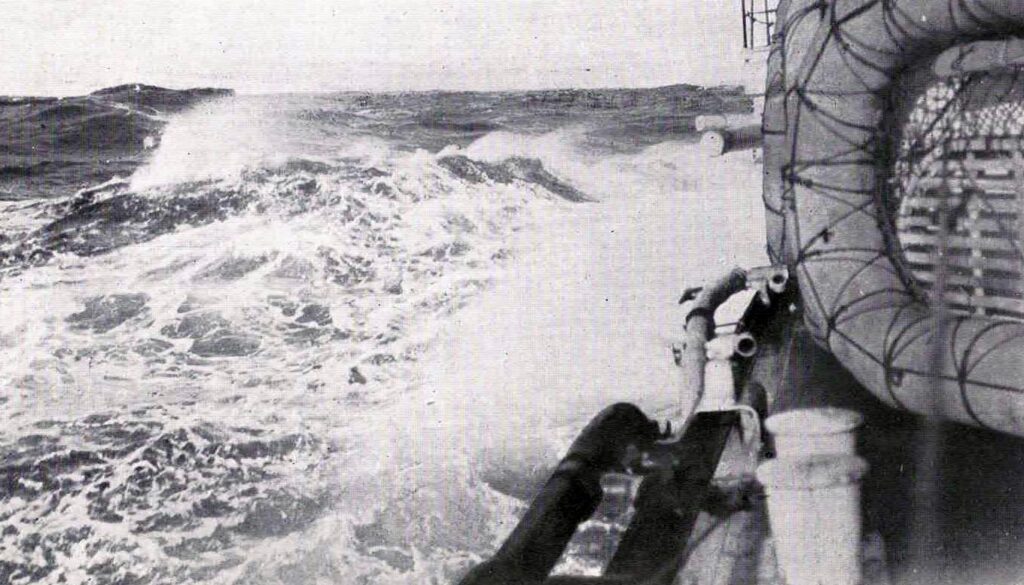

The St. Louis participated in six more convoys, totaling more than a hundred ships, which carried thousands of soldiers and cargos of supplies. During one February morning in 1918, the St. Louis battled strong gale force winds. The ship’s war log described the sea with 30-foot waves cresting above the ship “in a wild cross.” With good seamanship, the St. Louis stayed on course until the weather moderated in the afternoon. The war log crows about the crew “having sent old Neptune down for the count.”

The crew got occasional breaks between harrowing convoy runs. While on furlough in June 1918, Daly returned to Ventura and married Effie A. Barlett. Immediately after the ceremony, he returned to the St. Louis.

Despite the dangerous duty escorting vulnerable ships across the Atlantic, only two deaths were reported at sea. In early 1918 one sailor was lost when he was washed overboard. Two weeks later another sailor died of unspecified “respiratory problems.” The St. Louis was not immune to the effects of the growing “Spanish Flu” pandemic. While in the Navy Yard at Norfolk, Virginia in March 1918, 73 sailors contracted the flu. Three sailors died. None of them were from the Ventura militia.

While constantly on alert for submarine attacks, the ship’s war log reports some humorous episodes with the ever-vigilant lookouts. On one trip, another ship in the convoy attacked a suspected submarine. When the St. Louis arrived to help, they found the gunners were firing on an “inoffensive iceberg bobbing placidly in the water.” Another time, the ever-ready gun crews were called off in time when the “danger” proved to be an inquisitive whale.

End of the War

Ventura got word the war had ended at 12:24 a.m. on Monday, November 11, 1918. There would be no quiet in the town as the news spread quickly. The Mission’s bells were rung. Fire bells and other church bells joined in. As soon as enough steam could be generated, a laundry whistle started to blow. The cord was tied down and whistle blew until the steam was exhausted. The Ventura Weekly Post and Democrat had produced an extra which was snapped up by revelers. The big city fire engine, followed by 34 automobiles “cavorted up and down every street in the town.” Several hundred people marched to the Armory where they danced in the street and sang “The Star-Spangled Banner.” City leaders reluctantly concluded that a formal victory celebration would be unsafe with the influenza pandemic still raging. No date was set, but Mayor Erwin Kellogg expressed hope that a city-wide celebration could be combined with the imminent opening of Ventura’s new bathhouse. The pandemic prevented the opening of the bathhouse for another five months. Ventura and Oxnard residents let down their guard during the public victory celebrations and may have contributed to another wave of influenza in both towns in early 1919.

The work of the St. Louis did not end with the armistice. In Portsmouth, New Hampshire, she was fitted for berths for 1,300 troops. She made seven round-trip crossings and returned over 8,400 troops from France. On a crossing in January 1919, she was in the center of a gale stronger than the one she battled in 1917. The sea sent “tons of green water tumbling over the decks.” Fifty knot winds ripped eight feet off the topmast and tore off the wireless (radio) antenna. By the time the storm had eased 12 hours later, the crew had rigged an auxiliary antenna for the ship’s radio.

Aftermath

Daly and all but one of the other militia volunteers from Ventura were honorably discharged on January 21, 1919, and returned home. The Ventura Weekly Post and Democrat reported in 1918 that former Hobson Brothers employee Allan Root had died in France on December 13 of influenza. The war, which at the time was unprecedented in the slaughter, carnage, and destruction it caused, took the lives of nine soldiers, two sailors and one marine from Ventura County according to the official state record of war deaths.

Almost immediately after this discharge, Daly took an interest in the American Legion. In August 1919, with Jasper Berry and R. N. Haydon he organized Ventura County Post No. 48. He served as adjutant of the post until May 1923 when Haydon appointed Daly as deputy county auditor. He would later be elected commander of the post. Daly showed a lifelong commitment to the welfare of former service members and was particularly involved in the legion’s efforts to aid sick and disabled veterans and their families. In 1930, Daly succeeded Haydon when he was comfortably elected Ventura County Auditor. He served less than two years before he suffered a heart attack and died at the age of 47. The Ventura Free Press described Daly as “a man of firm convictions and fearless, who performed his duties without fear or favor. He was always ready with a helping hand, willingly and gladly going out of his way to perform some service or give some accommodation to others. Nothing was too much trouble for “Charley Daly” as he was known by his many friends.”

World War I was the end of state naval militias. After the war, the naval militias gave way to a federally run Naval Reserve. While the young men of Ventura’s naval militia were all volunteers, Congress enacted the Selective Service Act in 1917 that required all men aged 18 to 45 to register for military service. According to the Morning Free Press, Ventura County sent 337 draftees, called the Liberty Boys, to Fort Lewis in Washington state where they were inducted into the Army. Of the 4.8 million Americans who served in the armed forces during the war, 2.8 million had been drafted. The draft was dissolved at the end of the war.

Seventeen years after the schoolgirl cracked a bottle of champagne on the bow of the St. Louis, the ship arrived at the Philadelphia Navy Yard to be decommissioned. The ship was held in reserve until March of 1930 when torches were used to cut her hull in pieces, and she was sold as scrap. The ship was destroyed in accordance with post war international treaties to limit and reduce the amount of naval armament.

Ventura never held a city-wide celebration of the first Armistice Day. By November 11, 1919, California’s governor proclaimed the day a legal holiday. President Wilson had not done the same at the federal level. The anniversary was marked quietly in Ventura. Banks and all other businesses closed except for the post office. The Morning Free Press noted that “no program of any kind has been arranged in the city or the county.” An afternoon baseball game drew a large crowd and Venturans were urged to celebrate the day with dancing at the bathhouse auditorium that evening. Armistice Day became a federal holiday in 1938. After the “war to end all wars” was eclipsed by World War II, November 11th was changed from Armistice Day to Veterans Day in 1954.

Make History!

Support The Museum of Ventura County!

Membership

Join the Museum and you, your family, and guests will enjoy all the special benefits that make being a member of the Museum of Ventura County so worthwhile.

Support

Your donation will help support our online initiatives, keep exhibitions open and evolving, protect collections, and support education programs.

Bibliography

- Booth, John H. “Naval Militias.” Master’s thesis, U.S. Army Command and General Staff College, 1995. https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/tr/pdf/ADA299020.pdf.

- Morning Free Press (Ventura). “All Businesses Will Close Tomorrow to Honor Soldiers.” November 10, 1919, 1.

- Morning Free Press (Ventura). “Commissions For Ventura Volunteers.” April 10, 1917, 4.

- Morning Free Press (Ventura). “Eighteen Volunteers Answer Their Country’s Call.” April 9, 1917, 1.

- Morning Free Press (Ventura). “Enlistment the Order of the Day.” April 5, 1917, 1.

- Morning Free Press (Ventura). “Local News Notes.” April 11, 1917, 4.

- Morning Free Press (Ventura). “Local News Notes.” March 23, 1917, 4.

- Morning Free Press (Ventura). “More Venturans Join Volunteers.” April 11, 1917, 1.

- Morning Free Press (Ventura). “Naval Militia Meet Courthouse Tonight.” April 3, 1917, 1.

- Morning Free Press (Ventura). “No Doubt of German Plot to Link Japan and Mexico.” March 1, 1917, 1.

- Morning Free Press (Ventura). “Patriotism is Marked at Notable Meeting.” March 29, 1917.

- Morning Free Press (Ventura). “Prompt Response of Young Ventura to Country’s Cal.” April 4, 1917, 1.

- Morning Free Press (Ventura). “The List From Which the Last of the Selectives Will Be Made Up.” October 5, 1917, 1.

- Morning Free Press (Ventura). “To Mobilize Navy.” April 6, 1917, 1.

- Morning Free Press (Ventura). “Ventura Has Record Boys Sent to Front.” April 12, 1917, 1.

- Morning Free Press (Ventura). “Ventura Naval Militia Volunteers Wlll Be Sworn In Tonight.” April 7, 1917, 1.

- Morning Free Press (Ventura). “Ventura Sends Her Best Men to Natl. Army.” September 21, 1917, 1.

- Morning Free Press (Ventura). “Ventura’s Yesterdays.” March 28, 1927, 4.

- Oxnard Press-Courier. “Armistice Day Nov. 11 is Legal Holiday.” October 25, 1919, 1.

- Oxnard Press-Courier. “Brusqueness and Truth.” March 16, 1917, 2.

- Oxnard Press-Courier. “Last Liberty Boys In the First Call Off To the Front.” November 3, 1917, 1.

- Sheridan, E. M. “Easter Reminds Ventura “Firsts” Who Went to War.” Ventura Weekly Post and Democrat, March 24, 1926.

- St. Louis (Steamship) [from catalog]. War log of the U. S. S. St. Louis, February 4, 1917, July 2, 1919. New York: Wynkoop, Hallenbeck, Crawford Company, 1919.

- State of California Adjutant General’s Office. Honor Role. Sacramento, CA: California State Printing Office, 1921.

- “U.S.-Mexico Relations.” Council on Foreign Relations. Last modified May 1, 2017. https://www.cfr.org/timeline/us-mexico-relations.

- “USS St. Louis (C-20).” Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia. Last modified June 4, 2024. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/USS_St.Louis(C-20)#References.

- “USS St. Louis.” Accessed September 4, 2024. https://freepages.rootsweb.com/~cacunithistories/military/USS_St_Louis.html.

- Ventura County Star. “County Auditor Daly Dies; Oliver His Successor.” June 20, 1932, 1.

- Ventura Free Press. “Committee Plans Big Demonstration Celebrate the Allied Victory.” November 29, 1918, 1.

- Ventura Free Press. “County Auditor Chas. Daly is Dead.” June 20, 1932, 1.

- Ventura Free Press. “How Ventura Celebrated Armistice Signing.” November 15, 1918, 1.

- Ventura Weekly Post and Democrat. “Allan Root Dies in Service.” December 27, 1918, 2.

- Ventura Weekly Post and Democrat. “How Ventura Celebrated.” November 15, 1918, 6.

- Ventura Weekly Post and Democrat. “More Sons of Ventura Rally to Old Glory’s Call.” April 13, 1917, 5.

- Ventura Weekly Post and Democrat. “The War Situation.” March 9, 1917, 6.

- Ventura Weekly Post and Democrat. “Two More Ventura Boys Pass Navy Exams Making Twenty.” April 13, 1917, 1.

- Ventura Weekly Post and Democrat. “Ventura May Have Naval Division.” April 6, 1917, 7.

- Ventura Weekly Post and Democrat. “Ventura Naval Militia and Red Cross Make Vigorous Campaign.” April 6, 1917, 8.

- Ventura Weekly Post and Democrat. “Ventura’s Youth Respond Nobly to Call of Nation.” April 6, 1917, 1.