By Andy Ludlum, Museum Volunteer

Paleontologist Ed Mercurio has called Ventura County a marvel of paleontological diversity. He told the Los Angeles Times, “you can walk through time…from underwater formations to tropical rain forests, in just a single canyon.”

Fossils of starfish and sand dollars dating back 55 million years have been found north of Ojai. In a Simi Valley canyon, giant alligators, 40-foot whale skeletons and a seven-inch tooth from an ancient great white shark have been found.

But this story is about four mammoths, the extinct Ice Age relatives of modern elephants. Three of the mammoths lived their days in Ventura County. The fourth was brought to the county and continues to delight school children today. Two of the mammoths are among the most complete skeletons of their kind ever found. One mammoth is so unique, it has been found only on the Channel Islands and three other island chains in the world.

County Road Builders Unearth Mammoth Bones 87 Years Ago

The Research Library houses huge bound volumes of the Santa Paula Chronicle. Browse the brittle, yellowed pages of the newspaper from 1932 and you’ll find a front-page article on November 26th headlined “County Road Builders Find Ancient Bones.”

Road builders were working on Foothill Road, three miles east of Ventura. Widening the roadway along the hills behind the county hospital to the east end of Poli Street, they made a 40-foot deep cut through heavy clay, gravel and rock. At one side of the road, as they were digging for drainage, they came across huge bones at least six inches in diameter and scattered over 50 feet. What appeared to be remnants of huge teeth, the size of a man’s doubled fist, were also found in the area.

One of the workers, H. W. Campbell of Oxnard, an amateur archeologist, asked the construction foreman, Frank Peters of Saticoy, to halt work until experts could be called in to identify the bones.

T. L. Bailey, a well-known geologist from Ventura, was called to examine the discovery. He told the Ventura Free Press he believed the bones were those of a mammoth 500,000 to one million years old. Bailey described seeing one of the mammoth’s tusks, which he said measured more than seven inches in diameter.

Despite efforts to keep it quiet, news of the exciting find leaked out and local spectators rushed to the site for a first-hand look. Peters had to hire round-the-clock guards. He worked carefully to secure some of the larger pieces to show the scientists expected to arrive soon from Los Angeles. A piece of bone believed to be a leg joint was left where it was found. A section of jawbone was also untouched.

By November 29th, the experts had arrived. Dr. Eustace L. Furlong of the Department of Paleontology at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena was so excited by the discovery he called in two field experts from his department to take charge of the excavation. According to the Caltech archives, Dr. Furlong and Dr. Chester Stock were well-known experts on vertebrate paleontology who put together a large collection of fossil bones.

The bones of the mammoth were to be taken to the County Pioneer Museum (which became the Museum of Ventura County) to be reconstructed as much as possible. It appears complete reconstruction was never possible as much of the mammoth was badly decomposed. The fragile bones had decayed to such a point that they were porous and chalklike and could easily crumble into pieces.

Parts of the mammoth’s tusk were given to E.M. Sheridan, curator of the Pioneer Museum for display. He also received a six-foot section of the top of the skull as well as several partially decayed bone fragments. The last we hear of the mammoth bones is in a January 28, 1933 article of the Santa Paula Chronicle in which Sheridan announces the skull of the mammoth was to be restored and placed on exhibition.

In 1932 and 1933, the museum added over 290 objects to its permanent collection ranging from gold miner’s spoons to ship models to saddlebags but no mammoth bones. They may have been returned to the finder. Dr. Samuel McLeod of the Los Angeles County Museum of Natural History said there is no “record of either a locality or a specimen that could fit those descriptions, either from the Caltech collections that we acquired in 1957 or in the LACM collections.” Dr. Jonathan Hoffman of the Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History also says there are no records in their catalogs of a 1932 specimen.

Who Thought Mammoths Could Swim?

In 1994, paleontologists discovered the fossilized remains of a pygmy mammoth on Santa Rosa Island. It was 95% complete and was considered the most complete skeleton of a pygmy mammoth ever found. So, what is a pygmy mammoth? In contrast to the Columbian mammoth which stood as high as 14 feet and weighed 20,000 pounds, the pygmy mammoth stood five to eight feet high and may have weighed as little as 2,000 pounds. They’ve only been found on four island chains in the world, among them the Channel Islands.

Somewhere between 20,000 and 40,000 years ago, a small group of huge Columbian mammoths left on a swim that would lead to the evolution of a new species. During the Ice Age, the sea level lowered as ice sheets and glaciers grew. The lowered sea level exposed more of the islands and made them closer to the mainland. San Miguel, Santa Rosa, Santa Cruz and Anacapa islands were part of a super island known as Santarosae, which was four times as large as the modern Channel Islands.

Hungry mammoths had heavily grazed the mainland and swam towards the scent of lush vegetation six miles away on the big island of Santarosae. (Modern elephants are excellent distance swimmers and have been documented to swim over 20 miles in search of food.) As the mammoth population on the island increased, food became scarcer. In addition, the island decreased in size as the sea levels rose as the glaciers and ice sheets began to melt. Within 20,000 years, evolutionary downsizing had given smaller mammoths, requiring less food, a distinct advantage.

Evidence of small mammoths on the Channel Islands had been reported since 1873. Caltech Drs. Stock and Furlong described the mammoth remains in 1928 and gave them the name Mammuthus exilis or “exiled mammoth.” (Remember Furlong would examine the Foothill Road mammoth in 1932.) Phil Orr, from the Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History did many of the early studies of pygmy mammoths on Santa Rosa Island. In 1959, Orr assembled a composite skeleton (composed of at least two adult pygmy mammoths) which is still on display at the museum.

On June 29, 1994, Dr. Tom Rockwell of San Diego State University’s Department of Geology noticed white bones sticking out from under ice plant on a hill on the northeast side of Santa Rosa Island. The principal investigator of The Mammoth Site in Hot Springs, South Dakota, Dr. Larry Agenbroad, was called in and he recommended immediate excavation of the remarkable find. The skeleton was exposed and cast in plaster. The plastered segments were carried by helicopter to a spot on the island where they could be placed in containers and taken by a National Park Service boat to a dock in Ventura. The bones were then transported to The Mammoth Site in South Dakota where they were cleaned, stabilized and preserved. They were finally returned to the Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History. Dating of the bones showed the mammoth, thought to be an elderly male, lay down on his left side and died 12,840 years ago.

Full-sized mammoths died out about 10,000 years ago. Isolated on the Channel Islands, the pygmy mammoth died off years later. Anthropologists believe Chumash Indian predecessors first settled on the Channel Islands 8,000 to 12,000 years ago, about the time the mammoths died out. There’s a chance human activity might have contributed to their extinction but inspection of pygmy mammoth bones has turned up no evidence that any of the animals were butchered. Overcrowding, rising sea levels, drought and fire may be other reasons for the extinction of the pygmy mammoth.

Rare Mammoth Unearthed by Housing Construction

Another mammoth became a one-day media star at least 750,000 years after it drowned in an ancient stream and its body was covered by flood debris. In late March 2005, TV helicopters circled over a 15-by-20-foot hole after bones were discovered by crews grading for a 265-home development in the Moorpark foothills.

The same mammoth expert who verified the pygmy mammoth find in 1994, Dr. Larry Agenbroad, told the Los Angeles Times this find was 50% to 70% complete and would be even more “spectacular” if it turned out to be the rare meridionalis (or Southern) mammoth which had never been found in coastal California.

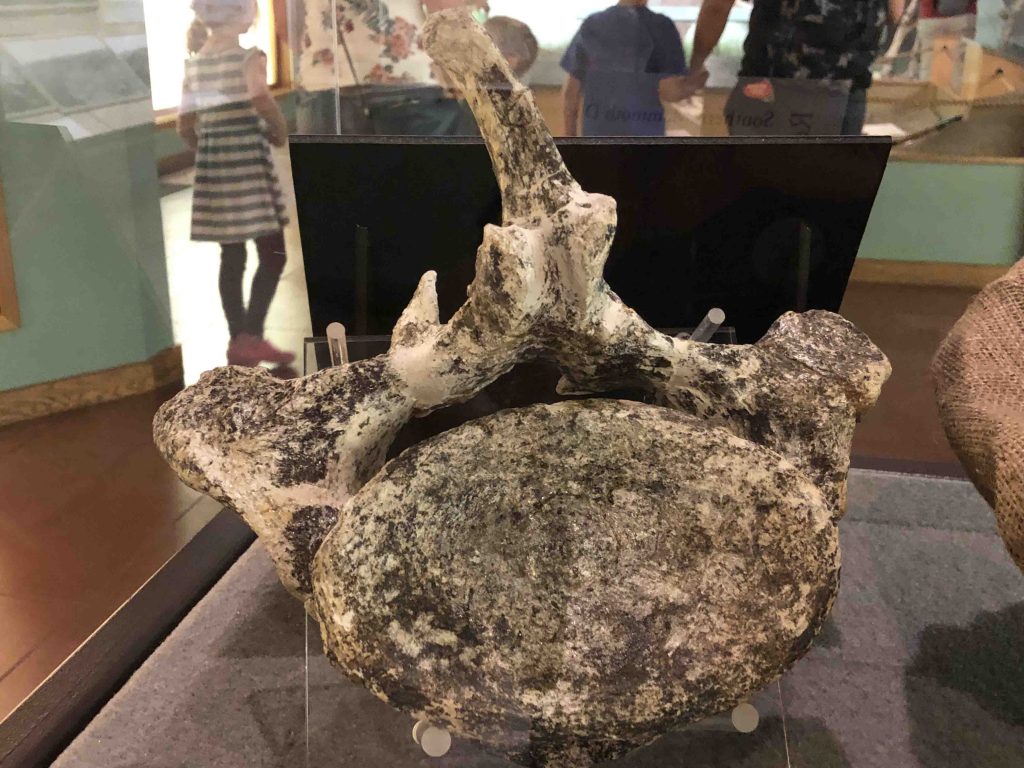

Fossils are frequently uncovered during home building and state laws require paleontological monitoring during construction. When the on-site paleontologist spotted small fragments of bones during the grading, he immediately stopped the work to take a closer look. A team of eight paleontologists worked quickly to remove the skeleton in nine days. They recovered pieces of backbone, nearly two complete legs, ribs, a large portion of the skull, a seven-foot section of one tusk and the tip of another and two huge molars. The bones were encased in plaster and wrapped in burlap and taken to a Santa Ana laboratory to be hardened with a special preservative.

In October 2007, the Moorpark City Council decided to donate the mammoth to the Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History, where the bones are on display today. The mammoth was confirmed to be the rare Mammuthus meridionalis. It stood 12 feet tall and had 8-foot tusks. It was estimated to be between 750,000 and 1 million years old.

A Mammoth Named Murphy?

This fourth Ventura mammoth never roamed in the county but is resting here as a favorite of school children in a small Ojai museum run by the Ventura Gem & Mineral Society. There the children can handle and even pose for pictures on a giant, resin-coated mammoth tusk named Murphy. (No one remembers why the mammoth was named Murphy.)

The Society’s Historian and Educational Outreach Chair Jim Brace-Thompson said a beloved past-president of the group, Bruno Benson, excavated Murphy’s tusk and tooth April 22, 1962 in Wilson Canyon, Nevada. They have photos of Benson and another club member, Bill Kirk, digging out the tusk, jacketing it in plaster and transporting it down the mountainside and into Benson’s turquoise-colored truck.

Benson, who passed away in 2000, founded the society’s first museum at the old Petrochem site on Crooked Palm Road north of Ventura and provided many of its specimens. The society was started as a club by teens in 1944 and has over 140 members today.

Ventura Gem & Mineral Society established the Ray Meisenheimer Memorial Museum, which is home to Murphy and the rest of the Bruno & Opal Benson Fossil Collection. Located in buildings at Camp Comfort (Ventura County Parks system) in Ojai, the museum is open by appointment which is explained on the group’s website.

Make History!

Support The Museum of Ventura County!

Membership

Join the Museum and you, your family, and guests will enjoy all the special benefits that make being a member of the Museum of Ventura County so worthwhile.

Support

Your donation will help support our online initiatives, keep exhibitions open and evolving, protect collections, and support education programs.

Bibliography – The Mammoths of Ventura County

- Agenbroad, Larry D. Pygmy (dwarf) mammals of the Channel Islands of California. Hot Springs, South Dakota: Mammoth Site of Hot Springs, SD, Inc., 1998.

- Bowers, Stephen. “The Mammoth.” In Extinct Monsters, 20-22. Fallbrook, CA: The Observer Press Print, 1894.

- Brant, Cherie. Keys to the County, Touring Historic Ventura County, 154. Ventura: Ventura County Museum of History & Art, 2006.

- Cox, Christina. “Moorpark mammoth lives on in Santa Barbara.” Moorpark Acorn, June 1, 2018. https://www.mpacorn.com/articles/moorpark-mammoth-lives-on-in-santa-barbara/.

- Deseret News (Salt Lake City, UT). “Paleontologist Digs for Clues on Fate of Pygmy Mammoth.” September 1, 1996. https://www.deseret.com/1996/9/1/19263413/paleontologist-digs-for-clues-on-fate-of-pygmy-mammoth

- Meyers, Jeff. “Digging Up the Past: The area is a treasure trove of fossil remains of ancient creatures, but you have to know what you’re doing to locate them.” Los Angeles Tiimes, December 22, 1994. https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1994-12-22-vl-11677-story.html.

- Monterey Herald. “Mammoth remains unearthed in California (SoCal – Moorpark).” April 7, 2005. http://www.freerepublic.com/focus/f-news/1379623/posts.

- “The Pygmy Mammoth.” National Park Service. Last modified June 21, 2016. https://www.nps.gov/chis/learn/historyculture/pygmymammoth.htm.

- “Pygmy Mammoths of the Channel Islands NP.” Geocaching. Last modified November 1, 2006. https://www.geocaching.com/geocache/GCZ5HB_pygmy-mammoths-of-the-channel-islands-np?guid=e5694844-f83e-49cd-b6ad-ef25b7f3d4e5.

- Saillant, Catherine, and Gregory W. Griggs. “A Mammoth Find in Moorpark.” Los Angeles Times, April 8, 2005. https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-2005-apr-08-me-mammoth8-story.html.

- Santa Paula Chronicle. “County Road Builders Find Ancient Bones.” November 26, 1932.

- Santa Paula Chronicle. “Expert Views Skeleton of Buried Mammoth.” November 29, 1932.

- Santa Paula Chronicle. “Skull of Mammoth Will Be Exhibited.” January 28, 1933.

- Ventura Free Press. “Bones of a Prehistoric Mammoth, Denizen of the Pleistocene Age, Found Near Ventura Co. Hospital.” November 28, 1932.