By Library Volunteer Andy Ludlum

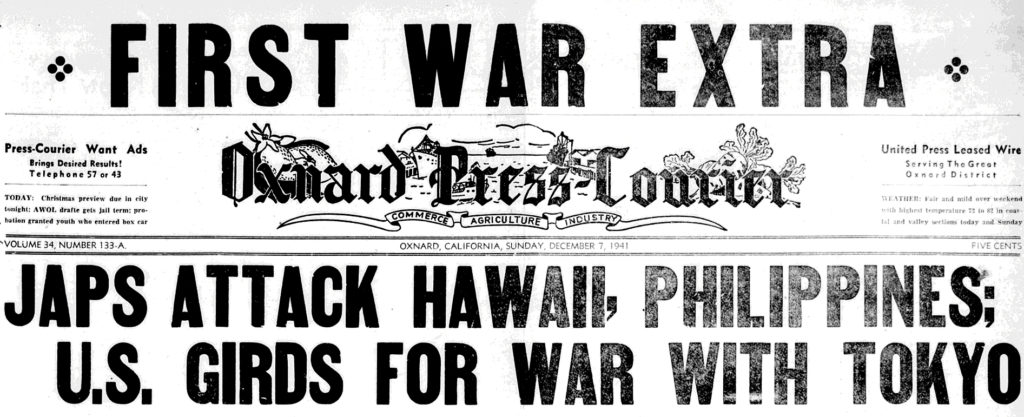

Oxnard Press Courier, December 7, 1941

The Sunday, December 7, 1941 edition of the Oxnard Press Courier ran a banner headline “FIRST WAR EXTRA” and described the surprise Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. Wartime hysteria and long-simmering racial prejudice would lead to 120,000 people of Japanese descent losing their homes, farms, jobs, and businesses as they were forced to spend the next several years in desolate concentration camps.

Blackouts, False Alarms, and Hysteria

After the December 7 attack, Oxnard and other west coast cities went on alert. Civilian aircraft observation posts in Oxnard were manned. The Ventura County Defense Council began signing up civilian volunteers reminding people that everyone in the county was “inherently obligated” to register for emergency service. Foreshadowing what was to come, the head of the FBI office in San Francisco said his men were “mobilized” in anticipation of a “presidential warrant” authorizing them to round up “dangerous enemy alien” Japanese and pro-Japanese suspects in the area.

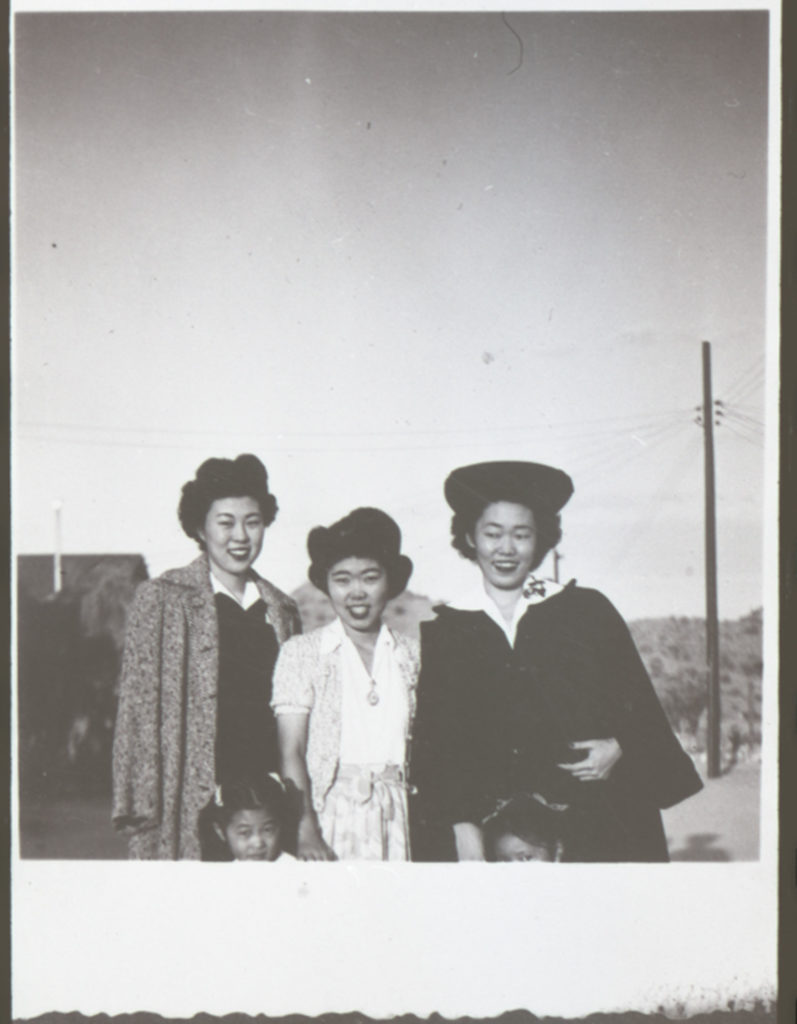

PN28224, MVC Library & Archives collection: http://photographs.venturamuseum.org/items/show/3512

Two days after the attack, the Port Hueneme lighthouse was blacked out at 7 p.m. The Coast Guard ordered the communities of Hueneme and Silver Strand to turn off lights. The harbor was closed and completely dark. Oxnard merchants agreed to shut their doors at 6 p.m. Drug stores would stay open one hour later, except for the Fifth Street store run by Jack Fiskin who called the closing a “hair-brained idea” and the result of “hysteria” by local authorities. The coming days were marked with unexplained false alarms. There was little to quell the hysteria. According to the Oxnard Press Courier, an excited Los Angeles woman called the police and said the Japanese “have landed and are advancing with tanks past the high school.” The enemy turned out to be street sweeping men and their “tanks” were big, motorized pavement sweepers.

On December 10, an Oxnard Press Courier editorial pleaded for calm, “False rumors, unnecessary scares and unfounded reports breed hysteria, hysteria brings ruin,” adding “there is little likelihood that Oxnard would ever be bombed…for this is a predominantly agricultural community.” The editorial cautioned against intolerance and snap-judgments, “There are hundreds of fine American-born Japanese in Oxnard…don’t let your rash actions hurt them.”

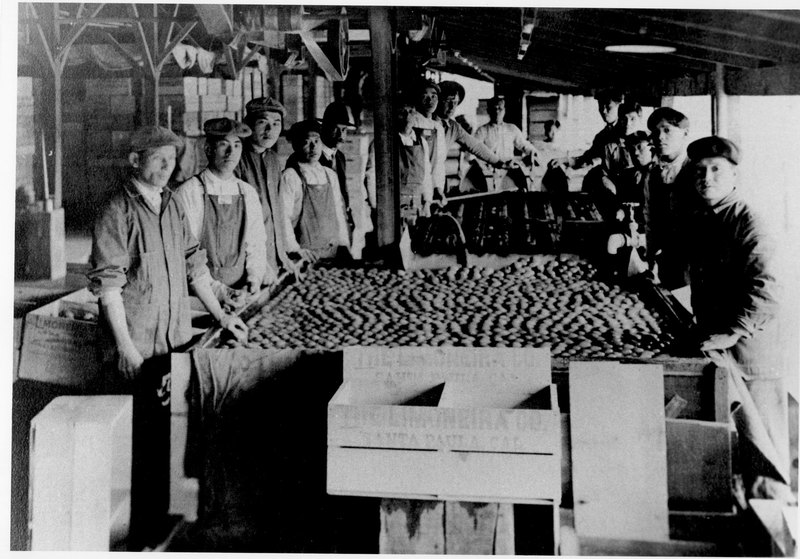

Japanese Immigrants Denied Citizenship

In the late 1890s, Japanese farmers were recruited to work the rich agricultural land around Oxnard. These new immigrants proved to be effective labor organizers. In Oxnard in 1903, an alliance of Japanese and Mexican sugar beet workers staged one of the first successful strikes by California farm workers. Striking farmworkers were seen as a threat to white landowners. They lobbied the state legislature to pass laws restricting the ownership and leasing of land by the Japanese. In 1924, the U.S. Congress passed the Alien Land Act and the Oriental Exclusion Act, putting an end to further immigration from Japan. This first generation or “Issei” was now barred from obtaining U.S. citizenship and could no longer own or lease land. Many got around this by putting titles of land or homes in the names of their American-born children or “Nisei.”

Sharing the front page of the newspaper on December 10 with the editorial pleading for calm, was a story on the arrest of a 25-year-old Oxnard farmer named Henry Hagaki. Witnesses told police they heard him threaten to “blow up the Oxnard Airport.” The Army ordered all roads adjacent to the airport restricted and armed sentries patrolled the area around the airport.

On December 13, Japanese farmers were urged to bring their vegetables to market, despite a government freeze on all Japanese assets. County Agriculture Commissioner Romain Young told the farmers to get their produce to “American” (white) firms for sale. The firms would hold the proceeds until plans were worked out to permit payment. Young eventually received a “letter from the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco outlining procedures whereby Japanese nationals and native-born Japanese as well may carry on their business in a normal fashion.”

By mid-December, the harbor had reopened. Japanese American fishermen who had been banned from their boats returned, provided they were registered with the Coast Guard and carried identification cards. At the end of the month, all persons of Japanese ancestry were ordered to turn in radios, cameras, and guns. The Oxnard police station received 50 cameras, 30 radios, and 30 guns. Some of the radios were returned after technicians removed the shortwave receiving capability.

Demands Increase to Force Removal

In early 1942, there was growing pressure on the government to remove anyone of Japanese ancestry from the west coast. The Office of Naval Intelligence and the FBI had been conducting surveillance on the Japanese in America since the 1930s. Plans were developed six months before Pearl Harbor to arrest “dangerous enemy aliens” should war be declared.

Oxnard Boulevard shop owner Watura Kawata was arrested at his home on January 2. His sons were graduates of Oxnard High School. A few days later, the county sheriff conducted a “lightning raid” in the Garden City Acres district and arrested seven men, all described as “enemy aliens,” which had become a euphemism for the non-citizen, Issei Japanese. They were held by immigration authorities, often for months, before receiving a hearing and being released, paroled, or transferred to a camp. Sheriff Howard Durley said he was conferring with county and federal officials about the need for “immediate action.” He said a total of 17 “enemy aliens” had been arrested in the county since January 1.

Pressure continued to increase. Los Angeles Mayor Fletcher Bowron demanded the entire Japanese population in Southern California be moved several hundred miles from the coast. The Ventura County Board of Supervisors and the county grand jury adopted resolutions urging the immediate evacuation of all Japanese in California to an area more than 200 miles from the Pacific Coast. The resolutions named both “enemy aliens” and American-born Japanese.

Lieutenant General John I. Dewitt, head of Western Defense command, saw little distinction between Japanese nationals and Japanese American citizens. He had infamously proclaimed, “a Jap is a Jap.” Dewitt insisted they were a threat and should be removed from coastal areas. He told President Franklin D. Roosevelt that while he had no evidence of sabotage by Japanese Americans, it only proved “a disturbing and confirming indication that such action will be taken.”

Roosevelt’s Sweeping Order

The Oxnard Press Courier reported on February 19 that President Roosevelt had signed Executive Order 9066. It ordered the removal of “resident enemy aliens” from parts of the west identified as military areas. The Oxnard Press Courier reported the action was designed to “help authorities deal with American citizens of Japanese ancestry, particularly those who are considered as dangerous as alien Japanese.” It also authorized the Secretary of War to provide transportation, food and shelter for persons “excluded” from the military areas.

Within days, FBI agents made arrests in cities between Redding and Los Angeles. It was described as their most extensive raid yet in the drive to suppress “sabotage and espionage activities.” Masako Moriwaki, a 1941 Oxnard High School graduate, remembers word got around that the FBI was targeting Buddhist priests, Japanese language teachers, and leaders of Japanese organizations. As her father had been active in a prefectural society and the Buddhist Temple, she expected him to be rounded up. “We had my father’s clothes all ready because…we were sure they would come after my father.”

In late February, the Oxnard Chamber of Commerce unanimously passed a resolution calling for the immediate evacuation of “all members of the Japanese race whether alien or American citizens.” The Oxnard Defense Council demanded the Oxnard Airport and the surrounding area be declared a “defense zone,” calling for the immediate removal of Japanese families living there. Their presence threatened “the safety of aircraft, student pilots and other installations.” The council’s emergency resolution was directed to the commander of the Fourth Army, the President of the United States, California’s two U.S. Senators, and California 10th District Congressman Alfred J. Elliott. Elliott was known for his harsh and bigoted view of Japanese Americans with statements such as “the only good Jap is a dead Jap.”

Navy Buys Harbor, Takes Over Land Farmed by Japanese

On March 10, 1942, the Oxnard Press Courier ran its biggest banner headline since the attack on Pearl Harbor: Navy Takes Over Harbor for 1500 Acre War Base. Reporter James Felton described a “fast-moving sensational drama.” A veteran Navy construction officer, Commander H.W. Johnson had interrupted a regular meeting of the harbor commission board. “He pulled out his scarred pipe, filled it, struck a match, took a few puffs, watched the smoke curl toward the roof and then calmly remarked: ‘Gentlemen, someone saw your harbor up here and liked it. Now we want to buy it.'” Felton’s article concluded, “Just like that, years of work, agitation, promotion went into the discard for the sake of America’s war effort.” Ironically, what had started in 1872 as Thomas R. Bard’s dream of a commercial wharf at Hueneme had slowly grown into a harbor district and seaport that had just been completed in 1940. The Navy’s $8 million plan for the 1,500-acre base required the purchase of more than a dozen parcels of land including ranches, homesites and beach acreage. War Relocation Agency (WRA) records show several properties rented by Japanese families in Oxnard were taken over by the Navy.

By early March, General Dewitt had issued military proclamations to place most of the west coast off limits to Japanese Americans. The Los Angeles-based “alien control coordinator,” Thomas C. Clark said he hoped the Japanese would be removed within 60 days, but that “we are not going to push them around. We are going to give these people a fair chance to dispose of their properties at proper prices.” He admitted that many of the Japanese farmers had been “stampeded into selling their properties for little or nothing and it is our purpose to see to it that unnecessary sacrifices are not forced upon them.”

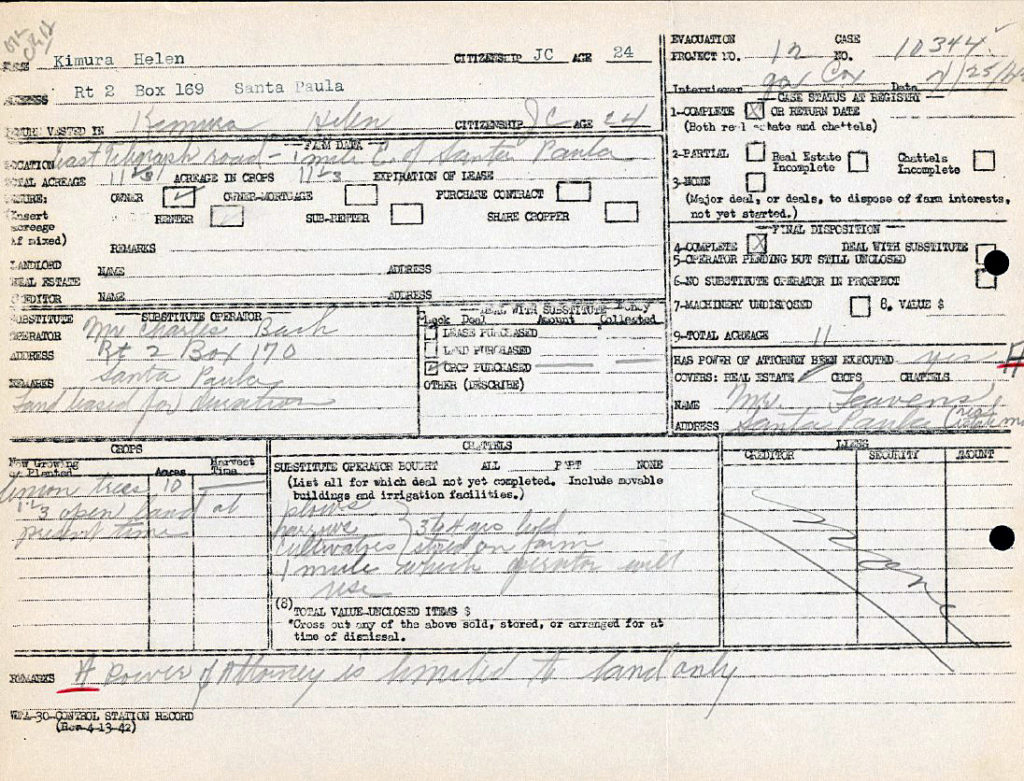

The reality was most of the Oxnard farmers were renters or had short-term leases on their land. The farmers quickly sold or returned rented farm equipment. Harvested crops were sold. Proceeds for crops still to be harvested were often applied against outstanding debts. Most of the Issei farmers left with nothing. Helen Kimura (Yamamoto) in an August 26, 1986, oral history interview with the Museum of Ventura County, said her father, an Issei, could not own land. Title to his Santa Paula property had been placed in her name. Her father said, “I will not sell this land on which I have worked so hard.” But he was concerned about his young lemon trees. “They’re going to die; no one to take care of them.” A neighbor, Charlie Batch, came by one day and said, “for what it’s worth, if you want to hang onto the land, I’ll see what I can do.” WRA records show Batch listed as the “substitute operator” for the land.

The Press Courier reported the Farm Securities Administration had opened an emergency office in Ventura to help “Japanese and enemy aliens to dispose of property in preparation to evacuating Ventura County.” An agent for the Wartime Farm Adjustment Program was at the office “to consult with farmers or other citizens who may be desirous of obtaining land or crops owned by the evacuees.” The agency later had to clarify it had not taken over the farms nor was it assigning new operators. They insisted they were only “bringing the Japanese and interested operators together and refereeing arrangements between the two.”

Small business owners either sold or found someone willing to care for their businesses. Shingoro and Yasuye Takasugi’s Asahi Market in Oxnard was left in the hands of employee Ignacio Carmona. Tomai Yeto was able to lease his market to a local woman. Records only list her last name of Gonzalez. Toraichi and Shina Otani’s grocery store was in a two-story building on Oxnard Boulevard. The business was on the first floor and the family of seven lived on the second floor. They piled everything they had to leave behind in one corner of the room upstairs. Friends moved into the residence to care for the property. Moriwaki remembers her family selling off most of what they owned. “We didn’t do anything wrong, but it was hysteria is what it was. We were Americans, but all they saw were our Japanese faces.” In an oral history interview with the Museum of Ventura County, Oxnard High School teacher Madeline Miedema remembers the Japanese American students leaving school in 1942. “But when they left it was such a sad thing. It was really a gift of public funds, but we let them take their textbooks with them.”

In this climate of tension and mistrust came the strange story of Oxnard farmer Yotaro Obana. Obana leased a truck garden on Santa Clara Avenue. He was arrested after a neighboring farmer, Calvin Moon claimed he had seen Obana destroy four acres of lettuce by pouring grain poisoned with strychnine over the crop. He said his pigeons died after eating the poisoned grain. Obana was tried and convicted of malicious mischief. He was fined $100 ($1,600 today) or 50 days in jail. He was also fined $1 for each of Moon’s 19 poisoned pigeons. Obana stayed in county jail until friends raised money and paid his fines. Three days later, County Agricultural Commissioner Young announced that the reports of sabotage were “entirely without foundation.” Young said the story had led to a “flood of inquiries” and a “mild hysteria apparently has been caused among housewives in particular.” Young said some poisoned grain was placed around the outer edges of the field for rabbit control. He did not debate whether the grain had killed Moon’s pigeons, but he insisted it “would not be possible to poison the lettuce in this way.”

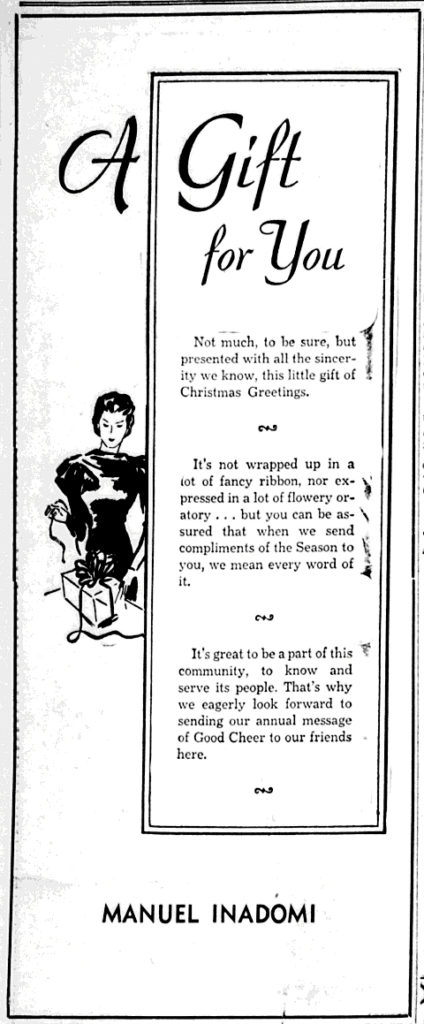

Well-known Japanese residents of Oxnard were now disappearing in FBI sweeps. Two prominent Japanese ministers were arrested. On March 20, the wealthiest and best-known Japanese resident in the county was whisked away by an FBI agent armed with a presidential warrant. Manuel Inadomi had owned Inadomi Markets in Oxnard, Ventura, and Santa Paula. He had been the treasurer of the Japanese Citizen’s League of Oxnard which had disbanded at the outbreak of the war. Inadomi was active in Oxnard’s civic and social life and was a member of the Rotary Club.

Order Sets Deadline for Departure

On March 27, General Dewitt issued a curfew order forbidding the “movement of all enemy aliens and Japanese Americans between the hours of 8 p.m. and 6 a.m.” They were also forbidden to leave the area to “prevent the indiscriminate evacuation of aliens to other states” to “ensure proper shelter awaits them at their destination.” In addition to the curfew, they were ordered not to “be more than five miles from his home except when traveling to his job or to an official alien control office.”

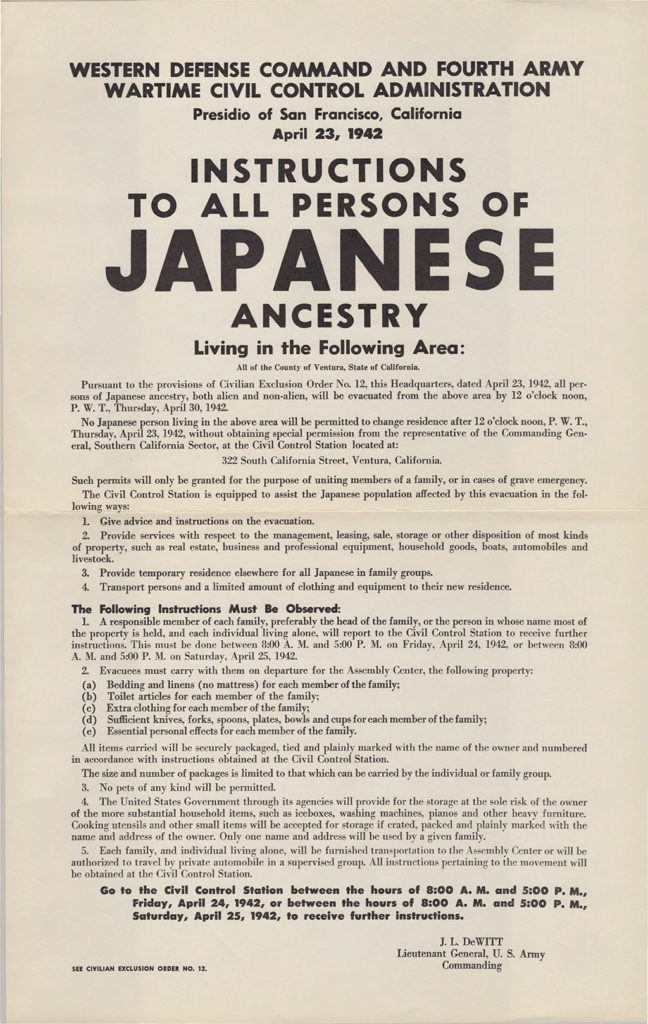

On April 23, General Dewitt posted orders that all people of Japanese ancestry would be moved from the county in one week. The posters said “evacuees” must carry with them bedding and linens, no mattresses, sufficient knives, forks, spoons, plates, bowls, cups, and essential personal effects for each family member. Eiki Kato of Oxnard recalled, “They never notified us by phone or by letter, they just hung the announcement on a post.”

Heads of households or single adults were ordered to report to the Civil Control Station at 322 South California Street in Ventura to make final arrangements for leaving their homes. The Oxnard Press Courier reported the “removal of 550 persons will clear the county entirely of Japanese.” They would go to the Tulare Assembly Center with 50 moving on April 27, 250 on April 28 and the final 250 on April 30.

Days before the deadline, the Chamber of Commerce appealed to Oxnard businesses to volunteer trucks and pickups to help take Japanese families to Ventura. Moriwaki remembers her parents had sold the family car and they had to be driven to meet the train to Tulare. “I was angry at the world. But it got to the point where you just had to live with it. What choice did we have?”

On April 29, Oxnard Press Courier reporter Kay Waymire described one of the last groups to leave Oxnard. “Stoically silent…wistfully sad…an adventuresome few, smiling as they contemplated the journey…343 Ventura County Japanese boarded six passenger train coaches at 9:30 this morning to begin the first lap of their journey to a new life ‘for the duration.’” The remaining “evacuees” were told to report to the Civic Auditorium at 8 a.m. the next day, wearing their identification tags and ready for departure.

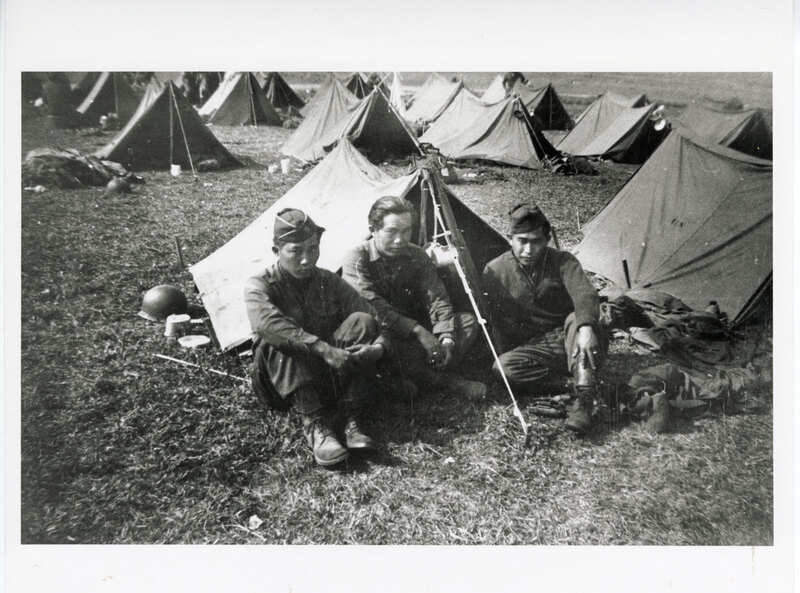

First Stop: Converted Horse Barns

The Tulare Assembly Center was a temporary detention camp, just outside of the city of Tulare in the southern San Joaquin Valley. It was built on grounds formerly used by the Tulare-Kings County Fair and racetrack. Kimura recalled riding the train to Tulare with the shades drawn. “There were vigilantes after us at the Tulare Assembly Center, because they didn’t want us even though we were going to be confined to this camp. But then the soldiers were there with their bayonets, and we walked through a line of these soldiers going into the camp.”

Nao Takasugi was valedictorian of the Oxnard High School class of 1939 and worked in his family’s Asahi Market. He was pulled out of UCLA at age 19 and sent to Tulare. “Put behind barbed wire and mounted searchlights and armed guards, I was very bitter. Of course, being 19 I was very idealistic and overnight all my dreams were dashed. Everything just happened so fast. We were confused and bewildered.”

The confined camp held over 5,000 people. Kimura remembers being searched for contraband and inoculated for typhoid. They were assigned to “barracks” which had been horse stalls that were quickly whitewashed for human habitation. She said, “My mother commented when we went into those little rooms, all whitewashed and white spray-painted, on how clean they were. But then the hay started to grow – they were horse stalls.” There were about 100 barracks within the fairgrounds and another 55 barracks to the south. The confined camp was occupied for less than six months. Their next stop would be a camp in the middle of the Arizona desert.

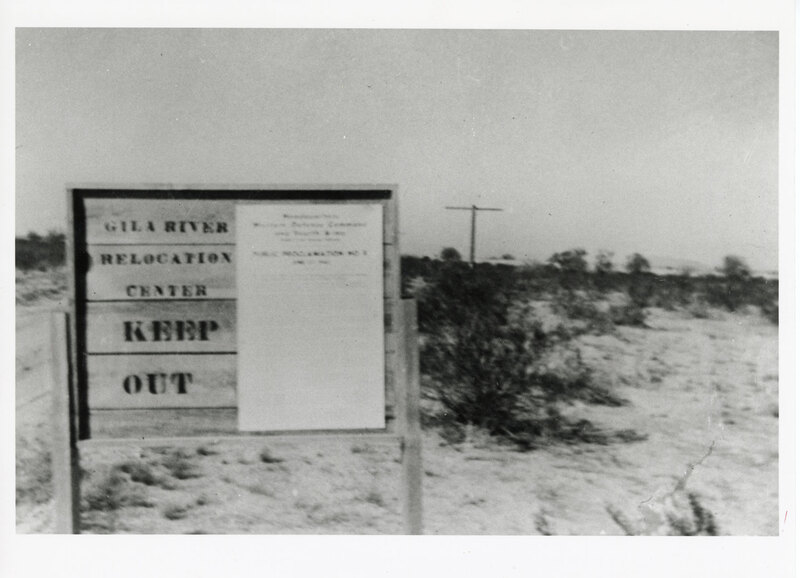

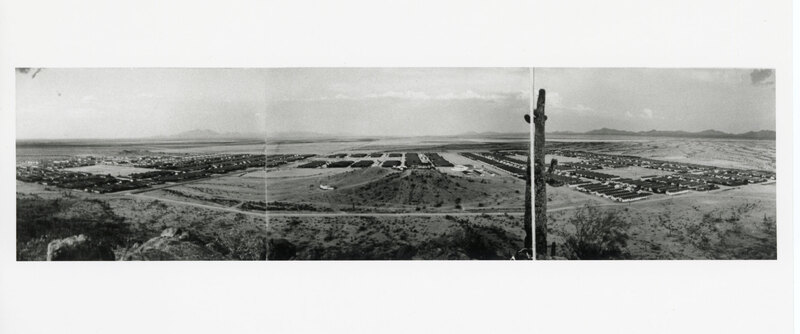

Gila River Camp Gets Off to a Rocky Start

The Gila River War Relocation Center was one of 10 camps built by the WRA. It was on the Gila River Indian Reservation, 30 miles southeast of Phoenix. Gila River was comprised of two separate camps, 3 1/2 miles apart, named Canal and Butte. Construction began on May 1, 1942.

It became Arizona’s fourth-largest city with a peak population of 13,348. Sixty two percent were American citizens. The Oxnard families arrived during the peak of the summer heat. July 1942 recorded 25 days over 105 degrees, while August had 23 days over 100 degrees and six over 105. The early days were plagued with problems. Gila River’s population was 4,000 over its intended capacity before construction was finished. Those assigned to barracks hung blankets to create walls for a little privacy. Some families had to temporarily stay in recreation and mess halls, even latrines. Everyone had an army cot and straw was stuffed between sheets to make mattresses. Stoves had not arrived. There was inadequate sanitation and poor toilet and sewage facilities which led to outbreaks of diarrhea and tuberculosis. The hot wind could stir up a fungus in the desert soil that caused fever, cough, and fatigue from an infection known as Valley Fever.

The barracks were approximately 20 feet wide by 100 feet long, made of wood frame and white beaverboard and had a double-roof design with red, fireproof shingles. Evaporative coolers were added to help make the temperatures in the barracks bearable but had to shut off during chronic water shortages. Some people dug “cellars” under the buildings to stay cooler. During a 1995 visit to the Gila River site, Thousand Oaks resident George Higa found the cellar he and his brother had dug out. “Being put in camp was a rude awakening. We thought we were Americans, but pretty soon you’re taken to camp and you find out that you’re something different.”

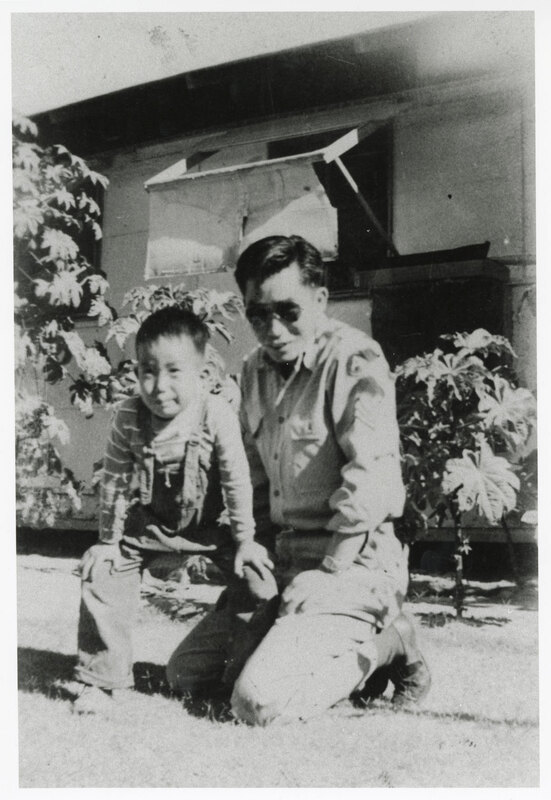

Leonard Takasugi was the oldest of 11 children and grew up on the Ventura County lemon ranch where his father Frank was foreman. He attended public schools, Ventura Junior College, and the Nisei Methodist Church in Oxnard. Leonard was drafted in 1941 and after basic training he visited Gila River to say goodbye to his family before deploying to Europe. Ironically, his family was under armed guard by soldiers in the same uniform he was wearing.

Kimura recalled the camp as “hot and awful. But it’s absolutely amazing…what people can do if they choose…eventually schools were set up, hospitals were set up and volunteers…manned the different departments.”

When completed, the two camps at Gila River had over 1,200 buildings including 859 residential barracks. There were latrines, showers, and laundry rooms. Schools, churches, and community service buildings were built. There was a store, dry cleaners, barber and beauty shops, even a gas station. There were administrative buildings, staff housing, and utilities such as a water filtration plant. Like a small city, Gila River had police, a court, and a post office.

Gila River was considered one of the least oppressive WRA camps. It had only a single watchtower, and the barbed-wire fences were removed early on. Administrators were lenient in granting permission to leave camp to go to nearby Phoenix, though a strict policy required check in upon returning.

Gila River had a “democratic” governing body, closely supervised by the WRA. A representative of every block was nominated to the council, however only Nisei could hold office. Due to their American citizenship and fluency in English, camp administrators preferred the Nisei as spokespeople for the Gila population, creating tension between Issei and Nisei in the camp. There was also tension between the camp and the surrounding community. There were wild accusations in local newspapers, that the Gila River population was getting milk before the local Arizonans and that they were not “patriotic enough” to help with the annual cotton harvest.

This led to a surprise visit by first lady Eleanor Roosevelt in 1943. She came to investigate charges that the federal government was “coddling” the Japanese Americans. Roosevelt’s published observations described the austere living conditions in the camp. She also concluded, “A Japanese American may be no more Japanese than a German-American is German, or an Italian-American is Italian…we cannot progress if we look down upon any group of people amongst us because of race or religion.”

Gila River had a theater for plays and films, playgrounds, and trees were planted. It became known for its baseball team, the Gila River Eagles. Semi-pro ball player Kenichi Zenimura was sent to Gila River in 1942 and was so depressed he did not open his suitcase for two weeks. To bring back a sense of normalcy, Zenimura started building a baseball field. His efforts grew into a 32-team league, with teams traveling to other WRA camps to compete.

The Gila News-Courier was the camp’s main publication. Like any small-town newspaper, News-Courier provided a variety of information concerning daily life. The newspaper was subject to editorial interference, in some cases overt censorship. WRA photographers had to live with peculiar rules. Sad photos hurt the camp’s image. Photos that were too happy were rejected as well. It was feared they would make the camp administration look like “coddlers.”

With limited resources, camp schools educated several thousand students from kindergarten through high school. The typing class had only two typewriters, so students practiced on cardboard diagrams of keyboards. George Wakiji had not finished 8th grade when he and his family were taken to the “relocation center.” “That’s what they called it, but it was prison to us.” Wakiji finished high school at Gila River.

More than half the adults in the camp worked, albeit for low WRA-set wages. They either grew produce, raised livestock, or worked in war production. Because of wartime shortages, the WRA wanted the camps to grow their own food. Farmers, even those from cooler coastal climates like Oxnard, quickly made the desert bloom with acres of beets, carrots, celery, and other vegetables. One year, it took 84 train carloads to carry a staggering four million pounds of produce to the other WRA camps. In 1943 raising livestock was added to the agricultural program. To aid the war effort, a camouflage net factory was briefly in operation at Butte Camp and employed 500 people. A model ship building shop at Canal Camp provided models for use in military training.

WRA Encourages Japanese Americans to Resettle

In 1943, the WRA began intensifying its efforts to resettle the Japanese Americans. They would be offered “leaves” to live and work in communities in the Midwest and the East. When Oxnard’s Kiki Kato’s father left camp to work in the Midwest, he was just 9 years old and suddenly became the oldest male in the household. “They took my youth because I had to grow up so fast. There’s nothing anyone can ever do to make up for that.” Thousands of college students like Oxnard’s Nao Takasugi were released from camp to continue their education. Others chose combat, 487 men from Gila River enlisted in the U.S. Army.

The release was not without strings. The key was the successful completion of an “Application for Leave Clearance” form. This benign-sounding form came to be known as the loyalty questionnaire. It contained two controversial questions. Question 27 asked young men if they were willing to serve on combat duty when ordered. Older men and women were asked if they would be willing to serve in non-combat roles. Question 28 asked if they would swear unqualified allegiance to the United States and forswear any form of allegiance to the Emperor.

Those answering no to the loyalty questions became commonly known as the “no-no boys.” Justifications for their answers varied. Some Nisei, as American citizens, resented being asked to renounce a loyalty they had never held. Other young men were concerned that declaring their willingness to serve in combat would be effectively volunteering. The Issei who were barred from becoming U.S. citizens were concerned that renouncing their Japanese citizenship would leave them without a country.

Ninety percent of the population at Gila River answered the loyalty questions positively, but about 1,800 people were classified as “disloyal” for answering no to one or both questions. They were relocated to the Tule Lake War Relocation Center, near the California-Oregon border about 10 miles south of the town of Tulelake. In March 1943, additional guard towers, fencing and search lights were added as Tule Lake was hastily converted into the Tule Lake Segregation Center, a destination for anyone from the 10 camps whose answers were considered “disloyal.”

As War Ends, the Camp Closes

When it was announced in 1945 that Gila River would be closing, many of those who remained said they were afraid to return to California. Threats had been made and even the WRA discouraged them from going home. Some even tried, unsuccessfully, to remain at Gila River. One Issei said, “California or no California, I don’t want to leave this center. We are much better off here than we have ever been. I can’t see any sense in going back now.”

By late July 1945, all the classrooms had closed, and the cattle had been auctioned off. On August 6 Hiroshima was bombed. Three days later, Nagasaki was hit. On August 15, President Harry Truman announced the war was over. Surrender papers were signed in Tokyo Bay aboard the USS Missouri on September 2, 1945. Gila River was officially closed on November 16. Piles of makeshift furniture, dishes, and other items were left behind. The valuable water piping had been removed, leaving only broken concrete foundations. Over a third of those designated as disloyal and held at the Tule Lake Segregation Center asked to be repatriated to Japan, even though over half of them had been born in the United States.

Return to Ventura County

On September 24, 1945, the Oxnard Press Courier reported 20 Japanese American families, about 100 people, had returned to Ventura County. Another 100 people were expected in the coming weeks. The paper was careful to note the families had been screened by the army and FBI to be certain of their loyalty. Many of the Issei farmers felt they had nothing to gain by returning to California. One farmer said, “I sold my farm equipment at the time of evacuation. My furniture is gone too. If I go back, I must look for some job. But I don’t know just what. I am too old to start farming all over again.” The Oxnard district relocation officer predicted only 30 percent of the pre-war Japanese American residents would return to the county. According to the U.S. Census, there were half as many Japanese Americans living in Ventura County in 1950 than there were in 1940.

Some were fortunate. Tom and Akira Kurihara returned to the farm they owned before the war. Others stayed in the Buddhist church at 234 Sixth Street in Oxnard which had been converted into a hostel. Some elderly people lived in the church for more than ten years. Manuel Inadomi, the wealthy Oxnard grocer taken away by FBI agents in 1942, was sent with his family to Gila River. They eventually returned to Oxnard and continued to operate grocery stores for over 40 years. Another Oxnard grocer, Tomai Yeto, who had leased his market to a local woman, returned to find she had kept it running during the war and was able to reclaim his property. The friends who cared for Toraichi and Shina Otani’s home above their Oxnard Boulevard grocery store were able to save the home, but not the business. Otani’s three sons tore down the old wood building and started several businesses which evolved into Otani’s Seafood, a seafood restaurant at 608 S A Street in Oxnard. Kimura, whose father’s neighbor had volunteered to care for his lemon trees, got special permission to visit her land before the camp closed. “The house had been set afire several times and everything was rundown…but at least the trees were still there, and the neighbor had tried his best. I said, Papa, the land is still there.” Her mother and father returned to their Santa Paula farm.

Shingoro and Yasuye Takasugi had left their Asahi Market in the care of employee Ignacio Carmona. When they came back from Gila River, Carmona returned control of the store to the Takasugis. Their son Nao had been released from camp to finish his college education. He earned an MBA from the Wharton School of Business. He said he was turned down by multiple Philadelphia accounting firms. “They’d say, ‘With that Asian face, we can’t put you in the field.” He returned to Oxnard to work in the family business. But when the city turned down his efforts to get a new sign for the market, Takasugi decided to run for City Council. He won his first election in 1976 and became mayor in 1982. He served five terms as mayor and the maximum of three terms in the California State Assembly. Immediately preceding Takasugi as Mayor of Oxnard was dentist Tsujio Kato. He was just 4 years old when he was sent to Gila River. He would become the first Japanese American mayor of the city.

Apologies and Reparations

President Harry Truman signed the Japanese American Evacuation Claims Act of 1948. It allowed people of Japanese ancestry to file claims for damages for their loss of property. The program bogged down due to red tape and a burdensome process for proving losses.

The Civil Liberties Act of 1988 granted redress of $20,000 and a formal presidential apology to every surviving U.S. citizen or legal resident immigrant of Japanese ancestry incarcerated during World War II. President Ronald Reagan signed it, and said, “We gather here to right a grave wrong,” noting that the incarceration occurred “without trial, without jury. It was based solely on race.” The first checks were presented in late 1990. Accompanying the check was a formal apology signed by President George Bush, “In enacting a law calling for restitution and offering a sincere apology, your fellow Americans have. . . renewed their commitment to the ideals of freedom, equality and justice.” In February of last year, the California Assembly apologized for discriminating against Japanese Americans and helping the U.S. government send them to camps.

No one held in the WRA camps was convicted of espionage, sabotage, or crimes against the nation. Thousands of young Nisei fought in Europe and nearly 1,000 of them died. Oxnard’s Leonard Takasugi, who visited his family at Gila River in uniform, was killed in action in Northern Italy and awarded the Bronze Star.

Language of Incarceration

Many of the words used to describe the wartime incarceration of 120,000 people of Japanese descent remain controversial. Many Japanese American groups today see words such as “internment camp,” “internee,” and “relocation center” as misleading euphemisms. They contend other words are more accurate such as “American concentration camp,” “prisoners,” and “illegal detention center.” Kimura said, “Some people called them concentration camps, detention camps, relocation camps. In a sense it was a concentration camp because we had guard towers, and every night we had a bed count. They’d come and flash their light for bed count. How could we escape? Where would we go?”

Make History!

Support The Museum of Ventura County!

Membership

Join the Museum and you, your family, and guests will enjoy all the special benefits that make being a member of the Museum of Ventura County so worthwhile.

Support

Your donation will help support our online initiatives, keep exhibitions open and evolving, protect collections, and support education programs.

Bibliography

- 100th Infantry Battalion Veterans | Education Center. Accessed March 9, 2021. https://www.100thbattalion.org/wp-content/uploads/Takasugi-Katsumi-Leonard.pdf.

- “5 Things to Know About Arizona’s World War II Internment Camps.” Azcentral. Last modified January 30, 2017. https://www.azcentral.com/story/news/local/chandler/2017/01/30/5-things-know-arizonas-world-war-ii-internment-camps/96965004/.

- “An American Dream, Interned: Exhibit Highlights History of Grocers.” Pacific Coast Business Times. Last modified June 13, 2014. https://www.pacbiztimes.com/2014/06/13/an-american-dream-interned-exhibit-highlights-history-of-grocers/.

- Baxter, Kevin. “The Trust Factor.” Los Angeles Times, November 15, 1996, E1, E16.

- “California Apologizes for Japanese American Internment.” YourCentralValley.com. Last modified February 21, 2020. https://www.yourcentralvalley.com/news/california/california-apologizes-for-japanese-american-internment/.

- “Camp Tulelake.” Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia. Last modified August 25, 2008. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Camp_Tulelake.

- “Civil Liberties Act of 1988.” Densho Encyclopedia. Accessed March 9, 2021. https://encyclopedia.densho.org/Civil_Liberties_Act_of_1988/.

- “Custodial Detention / A-B-C List.” Densho Encyclopedia. Accessed March 9, 2021. https://encyclopedia.densho.org/Custodial_detention_/_A-B-C_list/.

- Felton, James. “Pearl Harbor Attack, 71 Years Later.” VC Reporter | Times Media Group. Last modified December 5, 2012. https://vcreporter.com/2012/12/pearl-harbor-attack-71-years-later/.

- Fukuyama, Yoshio. “Citizens Apart: A History of Japanese in Ventura County.” Ventura County Historical Society Quarterly 39, no. 4 (1994), 3-31.

- “Gila News-Courier (newspaper).” Densho Encyclopedia. Accessed March 9, 2021. https://encyclopedia.densho.org/Gila%20News-Courier%20%28newspaper%29/.

- “Gila News-Courier.” Online Archive of California. Accessed March 9, 2021. https://oac.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/kt6g5035p2/?brand=oac4.

- “Gila River Relocation Camp.” Academic Server| Cleveland State University. Accessed March 9, 2021. https://academic.csuohio.edu/art_photos/gila/gila.html.

- “Gila River Relocation Center: From the Perspective of the WRA Photos.” Discover Nikkei. Accessed March 9, 2021. https://www.discovernikkei.org/en/nikkeialbum/albums/584/?view=list.

- “Gila River Relocation Center.” Japanese American Veterans Association | The Japanese American Veterans Association Website. Accessed March 9, 2021. https://www.javadc.org/gila_river_relocation_center.htm.

- “Gila River War Relocation Center.” Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia. Last modified January 10, 2005. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gila_River_War_Relocation_Center.

- “Gila River.” Densho Encyclopedia. Accessed March 9, 2021. https://encyclopedia.densho.org/Gila_River/.

- “Internment Camp Survivors React to California’s Apology.” Last modified February 21, 2020. https://spectrumnews1.com/ca/la-west/politics/2020/02/21/internment-camp-survivors-react-to-california-s-apology.

- “Japanese Americans In World War II.” National Park Service History ELibrary. Accessed March 9, 2021. https://npshistory.com/publications/nhl/japanese-americans-ww2.pdf.

- “Japanese Americans Recall Life As Internees : World War II: Nearly 1,200 Trek to Arizona Desert to Mark 50th Anniversary of Camp’s Closure.” Los Angeles Times. Last modified March 19, 1995. https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1995-03-19-me-44695-story.html.

- “Jauregui: World War II Internment Camps All but Forgotten.” Accessed March 9, 2021. https://archive.vcstar.com/lifestyle/jauregui-world-war-ii-internment-camps-all-but-forgotten-ep-371367379-350675901.html.

- Kimura Yamamoto, Helen. “An Interview with Helen Yamamoto.” By Mary Johnston, Ventura County Museum of History & Art. Audio Transcription. August 26, 1986.

- Miedema, Madeline. “Interview with Madeline Miedema.” By Betty Powell, Ventura County Museum of History & Art. Audio Transcription. October 25, 1989.

- “No-no Boys.” Densho Encyclopedia. Accessed March 9, 2021. https://encyclopedia.densho.org/No-no_boys/.

- “Op-Ed: Japanese Internment Was Wrong. Why Do Some of Our Leaders Still Try to Justify It?” Los Angeles Times. Last modified February 20, 2019. https://www.latimes.com/opinion/op-ed/la-oe-maki-japanese-internment-20190220-story.html.

- “Our Story/Timeline — Otanis Seafood.” Otanis Seafood. Accessed March 9, 2021. https://www.otanis-seafood.com/our-story#about-1.

- “An Outsider’s Look at Our ’44 Seabees.” Accessed March 9, 2021. https://archive.vcstar.com/news/an-outsiders-look-at-our-44-seabees-ep-369924346-350202361.html/.

- Oxnard Press Courier. “60-Day Limit seen for Japs.” March 4, 1942, 1.

- Oxnard Press Courier. “Airport Area “Restricted”.” December 26, 1941, 1.

- Oxnard Press Courier. “Alien news of the week.” February 7, 1942, 1.

- Oxnard Press Courier. “Aliens Give up Radios, Cameras.” December 29, 1941, 1.

- Oxnard Press Courier. “Chamber Asks for Vehicles to Transport Japs.” April 27, 1942, 1.

- Oxnard Press Courier. “Chamber Urges Curfew for All Japs and Aliens.” February 28, 1942, 1.

- Oxnard Press Courier. “Closing Ban on Harbor Is Lifted.” December 16, 1941, 1.

- Oxnard Press Courier. “Defense Council Urges Airport Area Be Cleared of Jap Homes.” February 28, 1942, 1.

- Oxnard Press Courier. “FBI Conducts Sweeping Raid on Jap Aliens.” February 21, 1942, 1.

- Oxnard Press Courier. “FBI Raid Nets 5 County Japs.” March 16, 1942, 1.

- Oxnard Press Courier. “FDR Edict Hits Japs on Coast.” February 20, 1942, 1.

- Oxnard Press Courier. “Hueneme Blacked Out.” December 9, 1941, 1.

- Oxnard Press Courier. “Inadomi Taken Out of County.” March 20, 1942, 1.

- Oxnard Press Courier. “Jap Curfew Begins Here.” March 27, 1942, 1.

- Oxnard Press Courier. “Jap Farmers Urged to Move Local Produce.” December 13, 1941, 1.

- Oxnard Press Courier. “Jap Held in Threat.” December 10, 1941, 1.

- Oxnard Press Courier. “Jap Jailed for Crop Sabotage.” March 10, 1942, 1.

- Oxnard Press Courier. “Jap Produce Not Poisoned.” March 13, 1942, 1,2.

- Oxnard Press Courier. “Japanese Americans Returning.” September 24, 1945, 1.

- Oxnard Press Courier. “Japs Attack Hawaii, Philippines; U.S. Girds for War With Tokyo.” December 7, 1941, 1.

- Oxnard Press Courier. “Japs Musts Leave Local Area Next Week.” April 21, 1942, 1.

- Oxnard Press Courier. “Let’s Keep Calm.” December 10, 1941, 1.

- Oxnard Press Courier. “Local Japanese Arrested; To Be Held for F.B.I.” January 2, 1942, 1.

- Oxnard Press Courier. “Many Radios Cameras Here.” December 30, 1941.

- Oxnard Press Courier. “May Apply for Jap Farms.” April 9, 1942, 1.

- Oxnard Press Courier. “Navy Takes Over Harbor for 1500 Acre War Base.” March 10, 1942, 1.

- Oxnard Press Courier. “Office Opens to Aid Japs.” March 20, 1942, 1.

- Oxnard Press Courier. “Oxnard Stores Adopt Closing.” December 13, 1941, 1.

- Oxnard Press Courier. “Seven More Jap Aliens Arrested Near Oxnard.” February 6, 1942, 1.

- Oxnard Press Courier. “The Japs Are Cleaning Up.” December 20, 1941, 1.

- “Port of Hueneme.” World Port Source. Accessed March 9, 2021. https://www.worldportsource.com/ports/review/USA_CA_Port_of_Hueneme_168.php.

- “PROFILING PARANOIA | Local Japanese Survivors Give Stories of Time Spent in WWII Internment Camps to CSU Project.” VC Reporter | Times Media Group. Last modified July 27, 2016. https://vcreporter.com/2016/07/profiling-paranoia-local-japanese-survivors-give-stories-of-time-spent-in-wwii-internment-camps-to-csu-project/.

- Takasugi, Frank. “Interview with Frank Takasugi.” By Yoshio Fukuyama. April 16, 1991.

- “Tulare (detention Facility).” Densho Encyclopedia. Accessed March 9, 2021. https://encyclopedia.densho.org/Tulare_(detention_facility)/.

- Waymire, Kay. “Japanese Quit County.” Oxnard Press Courier, April 27, 1942, 1.

- “Whitening a California Citrus Company Town: Racial Segregation Practices at the Limoneira Company and Santa Paula, 1893-1919.” Project MUSE. Accessed March 9, 2021. https://muse.jhu.edu/article/444778.

- www.nerdmecca.com. “WW2 Gila River Japanese Relocation Center, Arizona – Ghost Towns of Arizona and Surrounding States.” Ghost Towns of Arizona Provides Pictures, Maps and Information on Ghost Towns and Locations Most People Don’t Know or Tend to Forget About. Accessed March 9, 2021. https://www.ghosttownaz.info/ww2-gila-river-japanese-relocation-center.php.