By Andy Ludlum, Museum Volunteer

Ortwin Holdt and his fellow workers stood on stools and peered over a fence in Saticoy to watch high school boys playing a strange team sport. It was American football, not the soccer that the 20-year-old Luftwaffe radar operator knew. But what was a German soldier doing in Saticoy in 1945?

Holdt was captured by American forces invading Nazi-held positions near Marseille, France in 1944. He was one of 425,871 prisoners of war, mostly from Germany and Italy, who were kept in 511 POW camps in the United States. Many of the prisoners worked as farm laborers. Saticoy was home to a farm labor camp for about a year from May 1945 until the spring of 1946.

During World War II, California’s large agricultural industry was vital to meeting the wartime demand for food. Ranches and farms were feeding troops around the world. About 15 million Americans had been called into military service. Over 20 percent of the pre-war work force was now in uniform, yet the agricultural industry was expected to produce more food with fewer workers. The farm labor shortage was especially severe for the hand-labor-intensive Ventura County fruit producers.

The war offered an unexpected source of replacement farm workers: prisoners of war. England had been capturing German soldiers since as early as 1941. But they didn’t have the room or money to care for them on their bombarded island. In 1942, the British asked the United States to help care for some of the prisoners. The first shipment of 50,000 POWs soon made the long voyage across the Atlantic to America.

The prisoners were moved into a system of POW camps, mostly in the South, Southwest and California. With the temperate climate, camps could be constructed and maintained with minimal strain on wartime fuel and building supplies. The Liberty ships bringing supplies to Europe had been coming home empty, so it was decided to load the ships with prisoners on the return trips. Holdt describes his 24-day trip on a Liberty ship as “a beautiful voyage – nobody got seasick, we lived on C-rations and could walk around the ship and there were no submarine attacks.” The slow-moving cargo ships were especially vulnerable to U-Boat attacks.

The POW camps were to be established on existing military bases. Early in 1941, the Army built Camp Cooke in a remote area of Santa Barbara County (now known as Vandenberg Air Force Base) as a tank training base. The camps were situated in rural areas in order to keep prisoners well away from defense industry plants.

Camp Cooke was one of five major POW camps in California. Because the larger POW camps could only place prisoners on a relatively small number of nearby farms, the branch camp system was developed so that laborers could live closer to the farms and orchards where they were needed. The first 584 prisoners arrived at Camp Cooke on June 16, 1944. Camp Cooke had 16 branch camps that were activated between July 1944 and December 1945. Saticoy had one of the largest of the branch camps and it was the last to be closed.

Ventura County Citrus Ranchers Request Prisoner of War Labor

Early in 1945, the Saticoy Lemon Association, made up of 22 major citrus ranchers in Ventura County, requested prisoner of war labor from the Army. They had heard of the successful use of POW labor in Chino, Goleta and Tulare. Army engineers provided the association with the design requirements for a branch camp. The association, along with state and county officials, selected a location for the camp along the coast at Seaside Park in Ventura. The Ventura Chamber of Commerce, urged on by local non-agricultural businesses, erupted in protest, claiming the camp would ruin events at Seaside Park. In February 1945, a compromise site was selected well outside Ventura city limits. Approval was granted for a camp on 18 acres of land about three miles south of Saticoy, east of El Rio near what is today the intersection of Central and Rose Avenues.

CL #87-37.1G Museum of Ventura County Library & Archives collection

Using German prisoners and contract labor, construction of the camp started immediately. On May 16, 1945 the Santa Paula Chronicle reported the camp was nearing completion. The paper reported, “It iss expected it will be ready for ‘occupancy’ by the middle of next week, although it was inferred that it may be two weeks before the first of several hundred ‘tenants’ arrive.”

Twenty of the 21 caterpillar-shaped wooden barracks in the compound had been completed. Each living unit housed up to 50 prisoners and gave the camp a capacity of about 500 men. At the time, the actual number of prisoners was considered a military secret and was not reported by the newspaper.

The Chronicle added, “The 10-foot (above ground) woven and barbed wire fence enclosure has been completed, as well as a smaller, special confinement area. The prisoners of war, who are doing much of the work on the camp, are very frank that they would rather be looking in than out. Two watch towers, diagonally across from each other, will give guards a full view of the camp. The barracks, each 20 by 100 feet, are heated by two oil heaters. The two large mess halls are connected by a 20 by 60 kitchen. Two 1000-gallon hot water heaters have been installed to supply the kitchen, and 16 showers, and eight double washtubs for laundry use. Floodlights will keep the camp completely illuminated at night.” All the services for the camp were to be provided locally but were supported by supply trucks from Camp Cooke.

POWs Begin Working Out of Saticoy Branch Camp

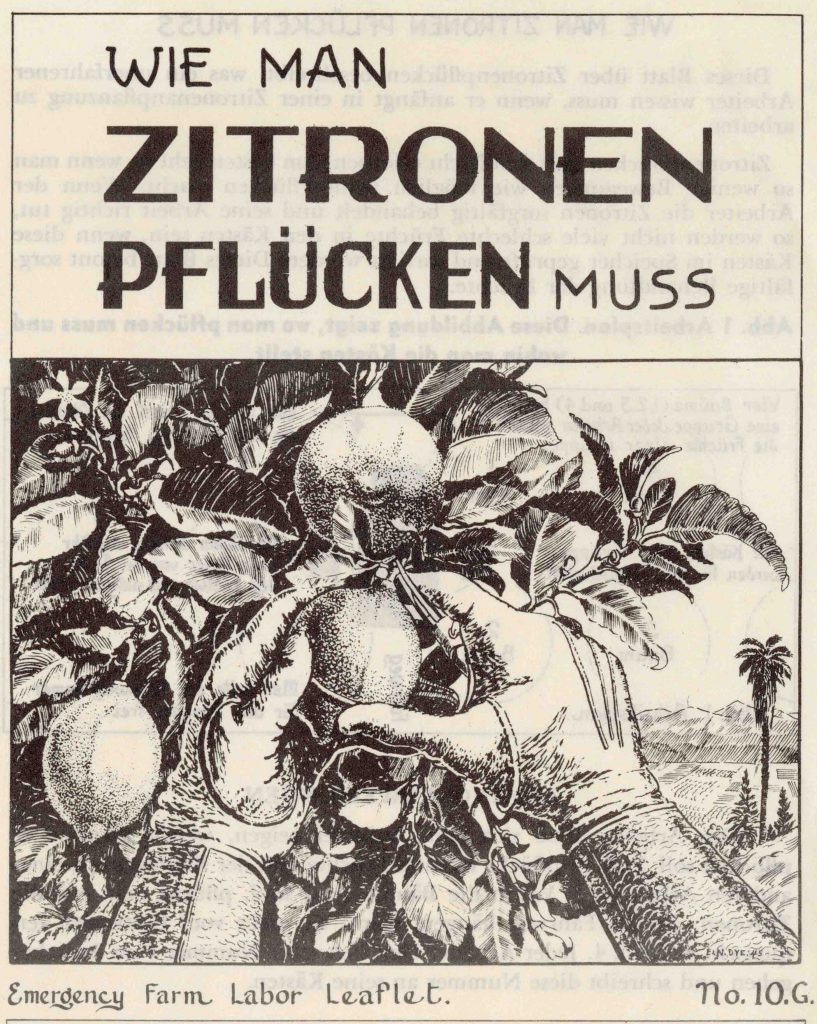

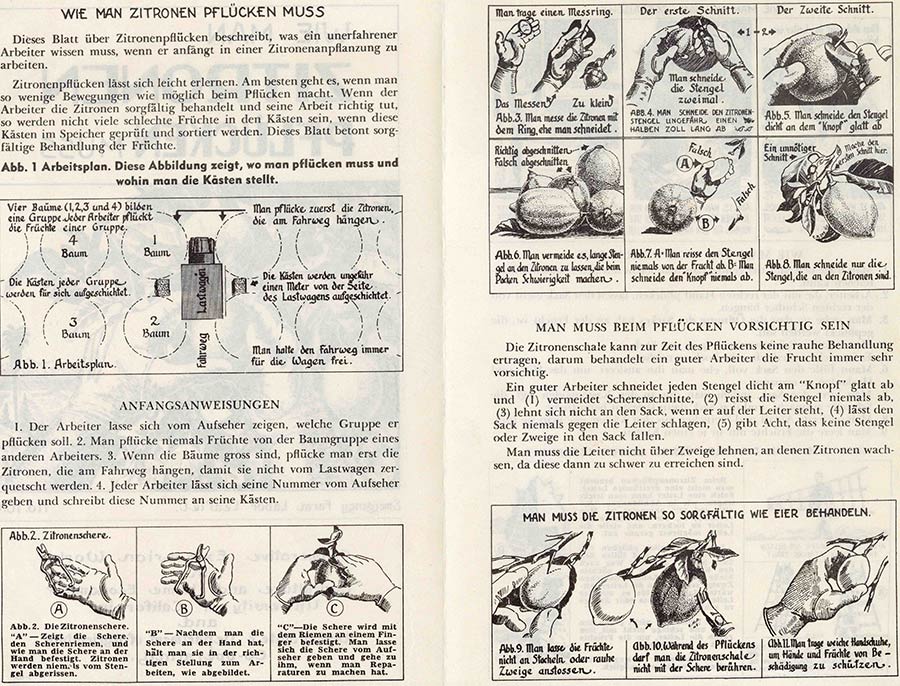

On May 28, 1945 the Chronicle reported German prisoners had started working in Ventura County citrus orchards under the watchful eyes of trained armed guards. The language barrier between POWs and farm bosses was a problem. The farm labor office of Ventura County introduced a training program for all prisoners assigned to the citrus fields. In the Museum of Ventura County’s collection there are two instructional leaflets, in German, describing the proper picking of citrus fruit. The Chronicle described the first day of instruction:

The extension service has employed four German-speaking trainers who will coach the prisoners in the fine points of picking citrus. The trainers who are experts in citrus culture, will go out with each detail. The Germans were shown colored pictures this morning on the picking of citrus…T.A. Lombard of the Rancho Sespe gave the prisoners a talk explaining the citrus industry, describing the work they will do, and outlining what was expected of them this morning.

Each prisoner of war working in the lemon orchards was paid 80 cents per day in PX credit, never cash for security reasons. The citrus growers paid the prevailing rates for the fruit picked. Any amount over the 80 cents per day, per prisoner went to the Army. Because the prisoners were paid less than the going market wages for regular farm workers, but more than what it cost the Army to maintain them, the government made money on the prison camp program.

Prisoners like Holdt would leave the Saticoy camp each morning to work in nearby orchards. In the evening they were taken back to the camp. For several months, Holdt picked lemons around Fillmore, Santa Paula, Ventura and Oxnard. He noted they used trucks that had both English and Spanish markings on them: “Exit Salida, 20 Hombres.” The Chronicle article on the opening of Saticoy POW camp ended with an update on the status of Mexican nationals working in the county. “The prisoners arrived with the news from the war food administration office of labor, who transports all foreign labor into this county, that California will receive no more Mexican nationalists this year. This means there will be 9000 less nationalists here this year than last.”

In the Saticoy camp, the rules of the Geneva Convention on prisoners of war were followed. The POWs lived in comfortable barracks and received good food and health care. A small emergency hospital was built to take care of sick or injured men. More serious illnesses were treated at Camp Cooke. There was a canteen with plenty of consumer goods that the Germans had not seen at home for many years. Some POWs wrote to their families telling them it was no longer necessary to send care packages. The prisoners were expected to form their own government and elect a spokesman. They were instructed on the principles of democracy and the free enterprise system in the hope that when they were repatriated, they would become leaders in creating a new democratic Germany.

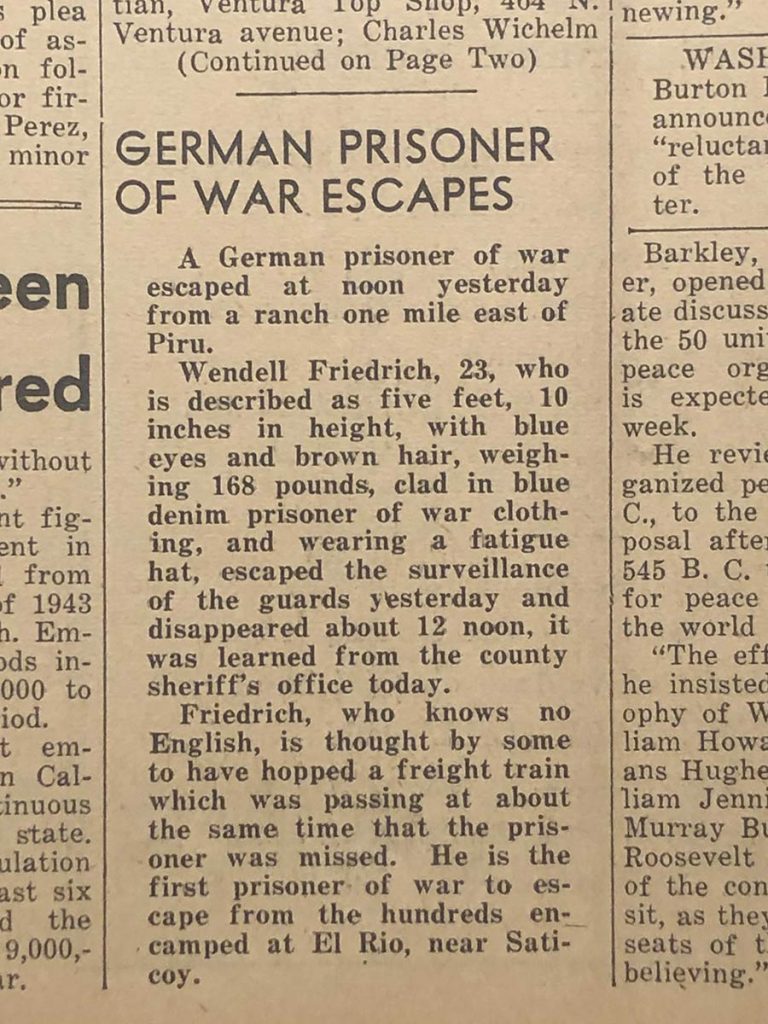

Saticoy’s Only POW Escape

Fewer than 1 percent of the almost 426,000 prisoners of war tried to escape. Saticoy did have one escapee. It was reported in the Chronicle on July 24, 1945 that 23-year-old Wendell Freidrich eluded guards and disappeared around noon the day before from a ranch one mile east of Piru. Freidrich, who spoke no English, was dressed in blue denim prisoner of war clothing. It was feared he might have hopped a freight train passing through the area at about the same time he disappeared. But Freidrich’s escape was short lived, he was found hiding out in Piru after less than two days of freedom. At the end of the war, only 17 German and Italian prisoners were still at large. The FBI had captured 11 by 1951 and the last one surrendered in 1985.

By July 1945 the war in Europe had been over for two months but Japan would not surrender until September 1945. The Moorpark Enterprise reported on July 5th that 75 percent of the season’s lemon crop had been picked. But the Ventura County Agricultural Commissioner described labor conditions as unchanged noting there was “still a need in citrus for packers, packing house help and in some cases pickers.” He said the use of prisoners of war had aided the citrus industry to some extent, but their efforts were not “sufficient to fill the full need.” He was expecting, now that school was out, that students would help meet labor demands for upcoming apricot harvest. By September 1945 it had become government policy to remove prisoners of war from jobs at Army installations if there were returned soldiers available to take the jobs. The Enterprise noted, “During the next six months several thousand prisoners of war utilized under private contract in agricultural pursuits…will be repatriated. More than half of all prisoners of war in this service command are being utilized to harvest crops and without their labor large quantities of food would be lost according to agriculture labor officials.”

As POW’s Leave, Ranchers Focus on Another Source of Labor

In October, the Enterprise reported Bill Williams, who led the U.S. Agriculture Labor Office for Ventura County, had told directors of the Ventura County Farm Bureau that German prisoners of war had picked 1,220,000 boxes of citrus fruit. He warned “a serious labor crisis might result this winter unless Mexican nationals were retained and unless housing was provided by the ranchers for year-round farm labor.” He warned that the 600 German prisoners of war at Saticoy would be removed shortly after the first of the year and that the Mexican labor contract expired December 31st.

The contract he referred to was what came to be known as the Bracero program which brought Mexican workers to the United States to help ease wartime labor shortages. The program continued well beyond the intended war years until 1964. Small farmers, large growers, and farm associations in California and 27 other states hired Mexicans as laborers during peak harvest and cultivation times. During the 22 years of the program, it was estimated that 4.6 million Mexican nationals came to work in the United States. The program was always controversial. Mexican nationals, desperate for work, were willing to take difficult jobs at wages rejected by most Americans. Farm workers already living in the United States worried that braceros would compete for their jobs and would lower wages. Many of the braceros faced discrimination and prejudice as well as injustice and abuse from dangerous substandard housing and unfulfilled contracts and were cheated out of wages.

With the war now over, the Enterprise announced on November 1, 1945 that farmers wishing to employ Mexican workers “between now and May 1, 1946 may file requests with the Farm Labor Office of the Agricultural Extension Service.” The paper reported the government was authorized to “extend employment agreements with Mexican national workers into 1946 as far as May 1st.” Extension beyond that date would require Congressional approval.

The Saticoy branch camp didn’t close until the spring of 1946. It took a long time to process the POWs for return. Holdt was sent to Belgium and turned over to the British Army. He worked on farms in England until he was repatriated in 1948. But he was not happy living in the ruins of post-war Germany. He returned to settle in this country in the 1960s and opened a business in Carpinteria.

The last signs of the camp disappeared in September 1946. The Enterprise reported the Saticoy Lemon Association would put the camp buildings and equipment up for sale on September 3rd. “Included in items for sale are 17 Quonset barracks and buildings, carpenter shop, pump and tool houses, ranges, galvanized iron sinks, oil burning water heater, heaters, toilets, wash basins, latrines, steel clothes lockers, oil tanks, drums and racks.”

Make History!

Support The Museum of Ventura County!

Membership

Join the Museum and you, your family, and guests will enjoy all the special benefits that make being a member of the Museum of Ventura County so worthwhile.

Support

Your donation will help support our online initiatives, keep exhibitions open and evolving, protect collections, and support education programs.

Bibliography

- “The Bracero Program, 1942-1964.” University of Northern Colorado – Greeley Colorado. Accessed December 9, 2019. https://www.unco.edu/colorado-oral-history-migratory-labor-project/pdf/Bracero_Program_PowerPoint.pdf.

- “Bracero Program.” Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia. Last modified December 11, 2004. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bracero_program.

- “Farm Labor Shortages During World War II.” Wessels Living History Farm. Accessed December 9, 2019. https://livinghistoryfarm.org/farminginthe40s/money_03.html.

- “German POWs on the American Homefront.” Smithsonian. Last modified September 15, 2009. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/german-pows-on-the-american-homefront-141009996/.

- “German POWs: Coming Soon to a Town Near You.” HistoryNet. Last modified February 13, 2019. https://www.historynet.com/german-pows-coming-soon-to-a-town-near-you.htm.

- Mandeel, Elizabeth W. “The Bracero Program 1942-1964.” American International Journal of Contemporary Research. Accessed December 9, 2019. http://aijcrnet.com/journals/Vol_4_No_1_January_2014/17.pdf.

- Martin, Philip. “The Bracero Program: Was It a Failure?” History News Network. Accessed December 9, 2019. https://historynewsnetwork.org/article/27336.

- Moorpark Enterprise. “Farm Labor Crisis Feared.” October 25, 1945.

- Moorpark Enterprise. “Mexican Labor Requests Urged.” November 1, 1945.

- Moorpark Enterprise. “Ventura Crop News for June.” July 5, 1945.

- Moorpark Enterprise. “Veterans Now Replacing All Foreign Labor.” September 27, 1945.

- Moorpark Enterprise. “Saticoy War Camp Material On Sale Soon.” August 15, 1946.

- Ruhge, Justin M. The Western Front, The War Years in Santa Barbara County 1937-1946 . Goleta CA: Quantum Imaging Associates, 1988.

- Santa Paula Chronicle. “German Prisoner Captured Near Piru.” July 25, 1945.

- Santa Paula Chronicle. “German Prisoner of War Escapes.” July 24, 1945.

- Santa Paula Chronicle. “Germans Arrive at Camp.” May 28, 1945.

- Santa Paula Chronicle. “War Prison Camp Near Saticoy Finished Soon.” May 16, 1945.