By Library Volunteer Andy Ludlum

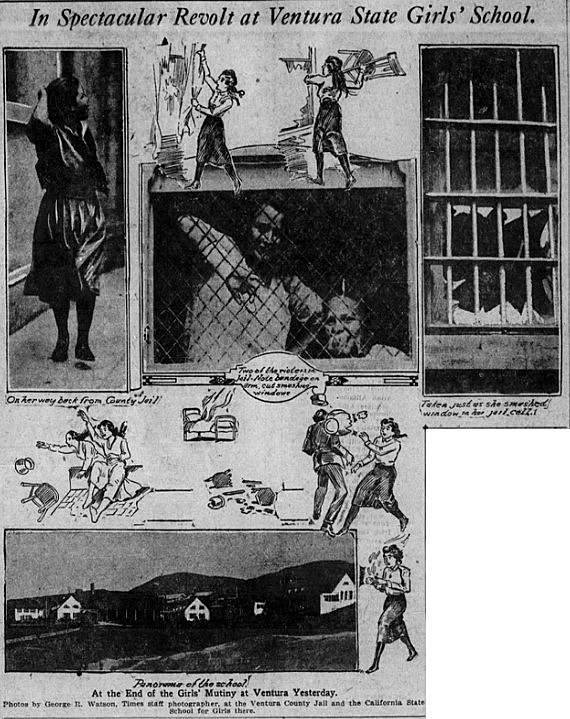

Ventura residents were shocked in February 1921 when they read about girls rioting at the local state training school. The newspapers described wild scenes in which screaming girls, wearing just their night gowns, shattered windows, broke furniture, tore down curtains, and threw flowerpots, stands and other articles at teachers from the roofs of the dormitory buildings. Other girls carried live embers in their bare hands and tried to set fire to the bedding. Readers wondered what had gone so terribly wrong at the school which had opened five years earlier as a source of civic pride and as a place where the young female wards would be “surrounded with an atmosphere of understanding and loving sympathy.”

When California became a state in 1850, there were no facilities for male or female juvenile offenders. While there was some talk of creating a “reform school,” there wasn’t the will or the money. Boys under the age of 20 who committed the most serious crimes were sent to state prisons. Between 1850 and 1860, 300 boys, some as young as 12, were sent to San Quentin and Folsom.

The California juvenile justice system was rooted in the philanthropic efforts of the 19th century “child savers.” The child savers, mostly white middle- and upper-class women, worked to address the plight of orphaned, abused, neglected, and delinquent children, mostly through institutional care. Their stated intention was to give troubled children good work habits, an elementary education, religious virtue, and respect for authority. But life in the institutions was harsh and even brutal. It was believed that structure and discipline were more important than nurturing and compassion.

First State School Called a “Nursery of Crime”

The San Francisco Industrial School opened in 1859 with 48 boys and girls ranging in age from three to 18 years old. Children were sent to the school by their parents, police, or the courts. The daily program consisted of six hours in the classroom and four hours of work. Over the next 30 years, the school was the source of frequent scandals involving child abuse including long-term confinement in dark cells and near starvation diets. When the school closed in 1892 one newspaper applauded the school being “wiped out at last,” calling it a “nursery of crime.”

The Whittier State School opened in 1891 for 300 youths. It housed boys and girls in two separate units and oversaw them separately. Beginning in the 1900s, the school’s operation came under the influence of the progressive movement. Progressives thought that human nature could be improved through the enlightened application of regulations, incentives, and punishments. They also believed human nature could be engineered and manipulated. Some even advocated selective breeding, or eugenics. Eugenics aimed to improve the genetic quality of the human population through policies that would encourage the more “desirable” elements of society to have children while preventing “undesirables” from reproducing. The racist logic placed white, Anglo-Saxon Protestants at the top of the hierarchy while immigrants, ethnic minorities, the poor, mentally ill, and developmentally disabled were at the bottom.

Progressives promoted science and education and condemned the harsh punishments at schools like Whittier. They believed scientific methods could transform delinquent youths into productive citizens. The reformers advocated the use of intelligence tests to determine the causes of delinquency. As a result, intelligence, race, heredity, and criminality became linked and misused. Test data was used as a basis for removing low scoring youth from the school, particularly Mexican and African Americans. Some of the boys, labeled as “feeble minded” were sent to state hospitals which were allowed by a 1909 state law to sterilize their wards. Researchers also tested the girls at Whittier, but the results of those exams have been lost.

In 1903 California became one of the first states to establish a juvenile court system. The act designated children as a separate class subject to their own legal system. The new juvenile court required trained and professional staff to give children individualized attention in a nonjudgmental manner. At the time there were more than 300 inmates at San Quentin were under the age of 16. In 1907 all boys under the age of 18 were transferred out of adult prisons.

A 1903 article in the Los Angeles Examiner reported that a male employee at Whittier had whipped one of girls, despite a ban on corporal punishment. Saying such practices “belonged to the dark ages” the sensational report led to a statewide investigation into mistreatment and cruelty. Ultimately, male employees could no longer impose “reprimands” such as whipping the girls or shaving their heads. The Examiner was a newspaper founded in 1903 by William Randolph Hearst. It was written in a style that became known as “yellow journalism” which used melodrama and hyperbole to sell millions of newspapers. Stories of abuse at the state schools became a favorite topic of the Examiner.

Club Women Lobby for State School for Girls

In 1911 the club women of the state started a campaign for a separate state training school for girls. The women’s clubs were based on the idea that women had a moral responsibility to transform public policy and had become an influential social movement. The club women pushed for reform on many issues including education, child labor and juvenile justice. They said Whittier had been inadequate in its care of girls. They said its small quarters and cramped conditions offered little opportunity for training.

In 1913, Governor Hiram Johnson told the state legislature that the “delinquent girls of California should be given equal opportunities for education and reform with the delinquent boys.” Influential women such as Mrs. C. M. Weymann, Secretary of San Francisco’s Juvenile Protective Association, pressured the legislature to act. They voted to appropriate $200,000 to establish the California School for Girls. A four-woman board, advised by State Engineer W. F. McClure, was appointed to find a site for the school on not less than “100 acres of good agricultural land.” The commission looked at 21 sites throughout California and triggered intense competition between Chambers of Commerce who viewed winning the school site as an economic triumph. Ventura’s Chamber brought out its heavy hitters; former supervisor, assemblyman, and Chamber President Thomas Gabbert, banker E.W. Carne, newspaperman and Chamber secretary Sol Sheridan, and Ventura Free Press Editor D.J. Reese.

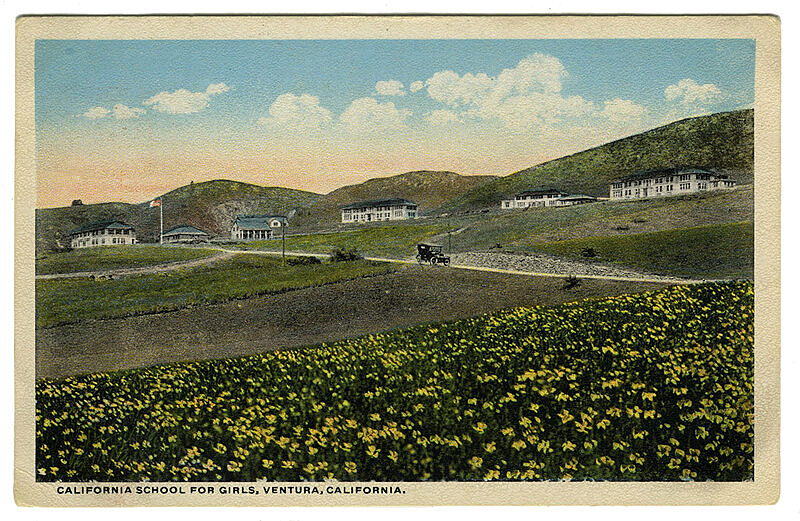

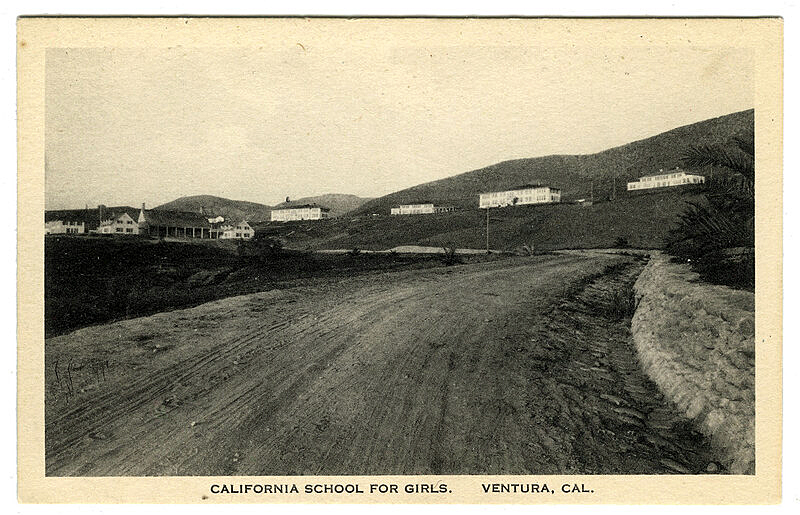

In December, a site was selected in Ventura, lying on the mesa and foothills on the east side of Ventura Avenue, almost opposite the Avenue school house. The Ventura County Power Company provided water facilities and county supervisors agreed to pay for a road to the site. The 125 acres was purchased for $22,000. Boosters described the site in glowing terms touting the “view of the Avenue below, the hills beyond and the ocean; unequaled climatic conditions; the nearness to the city and yet not being in the city, the fertility of the soil; the location on the coast, on the main line of the Southern Pacific and the State Highway.”

Trustee Predicts the School Will Solve the Delinquent Girl Problem in the State

A five-member board of trustees, all women, was appointed by the governor to manage the “state training school for the confinement, discipline and instruction of girls committed to it by law.” The board was directed to appoint a superintendent, “a woman qualified by training and experience at a salary not to exceed $2,400 a year.” This was generous as the average annual salary for a government worker at the time was less than $1,000.

The board was to see that “discipline is maintained, and that proper education is provided, to the end that those committed to its charge shall be prepared to become honorable, self-supporting members of society.” The school was to establish a course of study, “as far as practical,” corresponding to the public schools of the state. Facilities and equipment for vocational training such as “domestic science, dressmaking, horticulture, agriculture, and such business instruction as may be practicable” were to be provided “to each and every inmate.”

One of the trustees, Mrs. Edgar German of Los Angeles said, “Nothing could be lovelier than this location…Every girl will have an opportunity to develop her best self and to take up industry which really appeals to her. She will soon be returning from the school and be able to earn an honest living and be freed from the temptations besetting the inefficient worker.” Mrs. Weymann of the Juvenile Protective Association, now a trustee, said the school “is going to solve the delinquent girl problem for the state.” She added, “Every girl sent to that institution is…going to be trained to some kind of occupation that she thoroughly loves…There are plenty of laws to meet every need of the child; those laws are going to be enforced to the letter.”

Construction of the school began slowly. In March 1914 it was announced the school would eventually consist of ten “cottages” and an administration building/hospital. Trustee Weymann described the cottage idea, each designed to house about 20 girls, as a place “where every girl shall have some domestic duties where she can have a bit of garden where she can lead a normal, sane existence doing the things she most wants to do.” Only three buildings were constructed at first, two cottages and a hospital, enough space to house the girls at Whittier. It was understood as demand increased; the Legislature would provide more funding to increase capacity at the school to 300 girls.

Grading began in August. The foundations were poured in November and by January 1915 all three buildings were under construction. The Ventura Free Press continued to describe the site as if it was a resort destination where “the eye reaches out over the fertile valley below, commanding an unobstructed view of every detail of its beauty and splendor.”

The Board was also directed to immediately assume control over the girls’ department at the Whittier School. Board members attempted to make the school “as homelike as possible” and yet at the same time teach the girls to realize it is a training school. Trustee German said, “We believe thoroughly that by fostering a simple, true and lively pride in personal dignity and good taste, together with a joy and appreciation in work, we will do as much to make real this spirit of the State Industrial and Training School for Girls.”

The trustees had lofty goals. In their first annual report in September 1914, they said they intended to create a “physical culture” at the school through daily required work and help the girls develop character through their “own efforts.” They promised to make “loss of privileges” the only form of discipline and hire as officers “women of such culture and education that they may be a daily inspiration for the girls.” They also committed to “psychological examinations of every inmate in order to ascertain the actual causes of a girl’s failure to lead a normal life and to supply guidance for her training.”

The board closely supervised the construction of the new site along with the Free Press which continued to the take delight in the economic benefits of the school noting a “great deal of activity here, the payment of large sums of wages and the material benefit of every merchant in this city.”

Beginning in June 1916, the girls were quietly moved from Whittier to the new California School for Girls in Ventura. The “more reliable girls” were sent ahead to prepare the rooms and cottages for the others. Within a few weeks the entire school, 71 girls and 29 teachers or matrons, had been transferred.

The school’s Third Biennial Report in 1918 described an idyllic agricultural lifestyle with the girls caring for bees and producing 1,166 pounds of honey. They raised rabbits, turkeys, chickens, and pigs. They tended to goats which supplied the school with milk and cheese. They irrigated and harvested seven acres of alfalfa, all while keeping up with their schoolwork taught by the housemothers, who were qualified teachers.

The report showed only the rosy part of the picture. The school was home to a wide range of the state’s “troubled” female population. While many of the girls were delinquents, others had committed more serious criminal acts. Some girls wound up in the school for no greater crime than being judged “unruly” and promiscuous. Others were emotionally and mentally disabled. Farm work, charm classes, and church services would not work for all of them.

Abuse Scandal Triggers Investigation

At the end of 1918, a scandal erupted at the school after accusations were made of cruelty and misconduct by school authorities. In the Examiner, Los Angeles attorney Nellie Brewster Pierce described a so-called “water cure” of iced baths and other disciplinary measures to “cool the unruly spirits of rebellious girls.” Trustees responded by asking the State Board of Charities and Corrections to investigate the charges which they contended were “without foundation” and made by the paid attorney of “an admittedly delinquent girl.” In a letter to Los Angeles club women, the trustees accused Pierce of knowing that there had been no investigation and no facts established. They labeled the attorney’s accusations as “a sensational attempt to discredit…the school.”

Testimony during the first two days of hearings in Los Angeles didn’t help the school. Witnesses described the water cure in the “no privilege cottage” which consisted of turning “a three-inch fire hose on scantily clad girls and immersing them in an iced bath.” One witness said the girls were kept in the icy water from 13 to 20 minutes. A former inmate at the school testified she had seen the fire hose turned on a group of 10 or 15 girls.

Another witness, a former nurse at the school, Mrs. A. M. Newell, testified girls were given a shot of apomorphine as a measure of discipline. This made the girls vomit. Historically the apomorphine has had a variety of uses, but in the first half of the 20th century it was used to produce vomiting as part of aversion therapy. Newell testified the drug treatment was ordered, over the protest of the school’s doctor, by Mrs. Weymann, the former trustee who had become the first superintendent of the school. L. M. Loring, a graduate nurse who was employed at the school for more than a year, denied knowing of any instances where the girls were punished with shots of apomorphine. Ida Adams criticized the school for lax discipline declaring that some school officials were not competent to enforce discipline. Kate Gordon, a former kitchen matron, declared that she quit after just five days because the girls were “not amenable to discipline.”

The tone of the news coverage changed dramatically on the third and final day of hearings in Ventura. The Free Press said the school “had its inning today” adding the evidence presented during the first two days “was for the most part against the school and in a large measure given by “discharged and disgruntled former employees.”

Before the hearing, supervising matron Alice Eldridge gave a demonstration of the now infamous water cure. With Eldridge at the nozzle and another woman at the valve, the water was turned on and its force was demonstrated. Eldridge testified that she personally directed the hosing; that the hose nozzle was always 15 feet away from the girls and that the girls were dried, warmed, and given dry clothing and bedding. Eldridge, who had been at the school since it opened in Ventura, said she considered the water-cure more as a “treatment” than a punishment. “The water cure always had the effect of allaying hysteria.” She said the hose was only resorted to in “extreme cases” and not more than “three or four times in the history of the school.”

As for the no privilege cottage, Eldridge said the girls were sent there for gross infractions of the rules. The privileges which they were deprived of were music, reading, and companionship. She said the length of time the girls were kept there depended upon their behavior. She said the girls were given bread and coffee for breakfast, bread and soup at noon, and bread and tea at night.

After the hearing, Superintendent Weymann was defiant. She said the accusations had been made by a group of people who “are apparently neither familiar with the problem of the delinquent girl or the conduct of the said institution.” She said the school was “trying to assemble wrecks and to make them 100 percent women.” She recommended a hospital be established where experts could give the girls medicine and personal attention. She also asked the board of trustees to present to the state legislature a bill that would prosecute “any person or persons who may attack a state department or institution without first appealing to boards…to first investigate and report.”

While the Free Press concluded the school was “better understood today than it was before the investigation began” and that “its plans and purpose have been plainly brought to the attention of the people,” influential club women were outraged. Most of the trustees saw Weymann as the “storm center” of the charges of improper punishment. While it would not be announced for another four months, the trustees asked for Weymann’s resignation.

Weymann may have been out of the school, but she was not forgotten. When the administration buildings were completed in 1920, trustee Mrs. Seward Simmons “paid a most sincere tribute and a deserving one to Mrs. C.M. Weymann, the first superintendent of the school by whose untiring efforts the school was placed on a safe and sure foundation.”

The State Board of Charities and Corrections banned the water cure and limited other forms of punishment. But their action offered no solutions to an increasingly frustrated staff seeking to manage more than 100 girls of wildly different temperaments.

Simmering Tensions Result in Riot

The tension boiled over into a riot on Sunday night, February 27, 1921. The girls were unhappy that Superintendent Mary A. Hill had asked for the resignation of the school’s popular doctor, Martha G. Thorwick Di Giannini. A surgical nurse, Elsie L. Weeks had also been fired by the superintendent for “disloyalty” after she stated in the Ventura Daily Post that “a self-respecting person cannot be a part of the (school’s) system.”

When the girls learned that Dr. Di Giannini had quietly left the school the night before, there were outbursts in all the cottages. There were screams and shouts and the sounds of broken window glass. Chairs, tables, and dressers were broken “to kindling,” and curtains, bedding, and window shades were ripped. The girls climbed out on the veranda roofs and threw pieces of furniture and dishes at anyone who approached. The staff was unable to get near them. The Free Press reported the girls “yelled and howled like fiends incarnate” for more than four hours with their “nighties fluttering in the wind” making a “hubbub heard for miles.” In the confusion, nine girls ran away, but three were quickly caught.

The Free Press described Superintendent Hill and her assistants as “helpless, because the unwise state laws and unwise regulations of the State Board of Charities and Correction forbid any punishment.” Unable to restore order, they called Ventura County Sheriff Edmund G. McMartin who arrived with a posse of 16 deputies about 2:30 in the morning. According to the Los Angeles Times, the girls told Sheriff McMartin they had been advised that, as wards of the state, they could not be touched by the sheriff. The Times added “the girls showed they had full confidence in this advice by crowning Sheriff McMartin over the head with a chair and a few bits of furniture.” His posse was greeted with a shower of flowerpots, tables, and any other pieces of “ammunition” the girls could carry to the roof from inside the cottages.

Finally, what was described as a “garden hose” was turned on the girls. While they were fighting the water, the sheriff’s deputies entered the cottages. In one cottage the men “were kicked, scratched, bitten, chairs and tables and flowerpots were hurled at them.” During the struggle, Deputy Sheriff Juan Reyes was hit by a chair and knocked unconscious. Another member of the sheriff’s posse, former state assemblyman Joseph Argabrite was hit on the head with a vase. Attendant Lar Mante was bitten on the arm.

By about 3:00 in the morning, deputies had the upper hand and 25 of what the Free Press labeled as the “vicious ringleaders of the mutiny” were in handcuffs and taken to the Ventura County Jail. The school was quiet for a few hours. But soon after daylight, 11 girls in one cottage began screaming and breaking furniture. Attendants smelled smoke in one of the bedrooms. Burning coals had been hidden in the beds and covered with sheets and blankets. An investigation revealed some of the girls had brought live embers from the kitchen stove, carrying them in their bare hands. When school disciplinarian Winnifred Owens tried to quiet the girls and put out the fires, she was hit above the eye with a piece of a chair thrown by one of the girls. All the girls in the cottage were taken to the no privilege cottage and were given what the Free Press referred to as the “only punishment permitted at the school, i.e., placed in wet packs.”

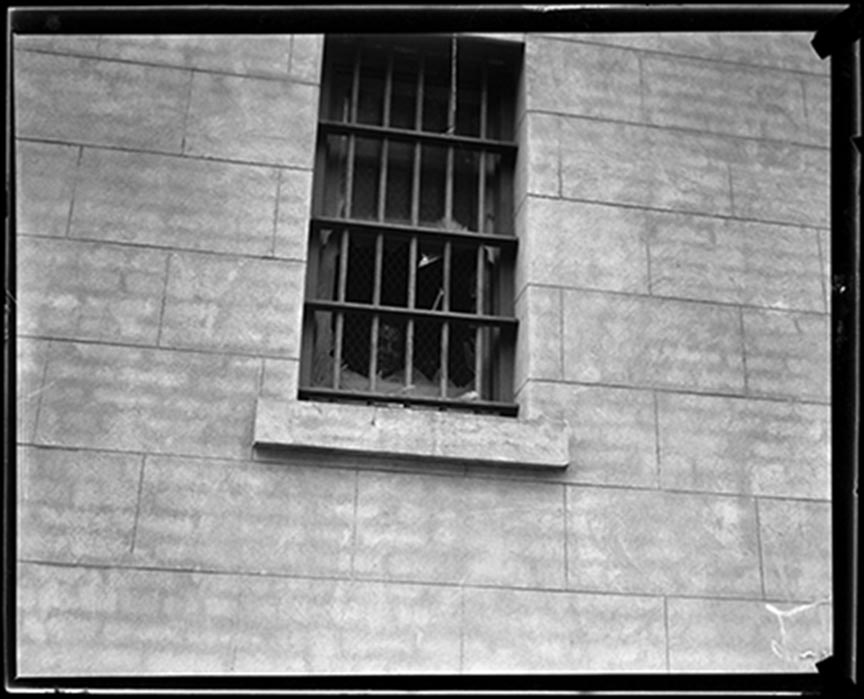

The 25 girls taken to the county jail were put in the “tanks” and continued their screaming and yelling. Jail tanks were large holding cells commonly used to confine drunks. Late Monday afternoon four of the girls were “repentant” and said they were ready to go back to the school, leaving 21 in the tank. That evening, 12 male guards from the Whittier State School for Boys arrived to help control the still unruly and active girls. The reinforcements allowed Superintendent Hill, along with a matron and two male guards, bring the jailed girls back to the school. They were taken out a back door, a few at time, to a side street where a large county automobile waited with its storm curtains drawn. Eleven unrepentant girls remained in the jail Tuesday night. They somehow obtained matches and set fire to the bedding in the jail. They wound up again in the tanks and were not taken back to the school until Wednesday afternoon.

Of the six girls who escaped Sunday, it was learned two of the girls had climbed aboard a truck bound for Los Angeles and disappeared. The other four were returned to the school late Tuesday evening.

By Wednesday, the regular routine of the school had resumed, windows and furniture were being repaired or replaced. The chaos had resulted in injuries to several girls, sheriff’s deputies and one member of the school staff. In addition to the 25 girls jailed, 100 girls had been detained in the “silence” room of the no privilege cottage. Damage to school property was estimated between $2,000 and $3,000 (nearly $50,000 today.)

Critics Claim School Officials Lacked Authority to Discipline

The events led the Free Press to take a more critical view of the school. The paper said, “It is high time that people should cease regarding the California State School as a finishing school for young women or as anything else than a reformatory for vicious girls. As a reformatory, the state school should have adequate laws to control the girls who were sent there by the courts of the state.” The paper complained that school officials were powerless to discipline the girls who were “generally criminals” and harder to handle than a prisoner at San Quentin. It cautioned against “breaking down the morale of the school by unwise and unjustified criticism.”

On Wednesday night, Superintendent Hill claimed there had been a conspiracy to stage the wholesale escape of all 160 girls. According to Hill, the girls planned to set fire to every building using live coals from their cottages. The simultaneous fires were intended to give them a chance to liberate the entire school. She blamed “recent sensational stories in Hearst’s Los Angeles Examiner which have helped stir up the spirit of rebellion and incite the girls to riot.” She called the reports “groundless” and inspired by “individuals who have their own motives for attacking state institutions.”

Hill said maintaining discipline and control at the school was a challenge. “The public should realize we have gathered together here a group of girls who are in the main emotionally unstable, whose mental levels differ widely and who all of the other agencies have failed to direct into right citizenship.” She said the ideal method of discipline had not been found at the Ventura school “or any other school of its kind, and this is a fundamental problem which has to be solved by the superintendent and officers of the school in conjunction with the board of trustees.” The trustees admitted appropriate discipline was “one of the most difficult problems of institutional work. After agreeing on an emergency plan, they stated that “school officials feel that they are equipped to handle difficult situations that might develop.”

News of the riot drew criticism from across the state. Santa Barbara Detention Home superintendent Anna McCaughey told the Santa Barbara News that the school is “the waste basket of the state” and “the women placed in charge of the school are given absolutely no control.” She added, “The girls find this out easily and then trouble begins.” A San Francisco woman, Harriet L. Taylor, blamed club women on the board of trustees for the “deplorable conditions at the school.” She said the board was “guided by the heart instead of by the brain.” Taylor said the board “broke into the affairs of the school when Mrs. W. C. Weymann was superintendent over a year ago and actually unseated the best superintendent the school will ever be able to get.” She added “Mrs. Hill is an efficient superintendent, but she has no authority, and the school is being run on sentiment instead of common sense.” Another social worker told the paper that the idealistic trustees “imagine that the girls who are sent to these reform schools are as easily guided and controlled as their own daughters.”

It’s unclear if events at the school were the impetus, but later in 1921 control of the three state correctional schools passed from local boards of trustees to the supervision of the newly created State Department of Institutions.

Hearst Paper Exposes Cruel Ice Pack Punishment

The muckraking Examiner was not done with the Ventura school. The paper published a series of articles written by Gladys Graff, a young University of California student who worked as a relief officer for five months in 1922. She claimed the methods of training and discipline at the school were “barbaric” and kept the girls “in a state of sullen resentment”, deadening “whatever hope or ambition they have in their lives.” Graff wrote that she witnessed disobedient girls placed on hard beds in dimly lighted cells in the cottage of no privileges and told to remove their clothes. If a girl refused, the women officers would strip her, throw her on the bed and sit on her until she was bound with broad bandages. An iced sheet was then wrapped tightly around her. Each ice pack punishment lasted four hours and a succession of packs continued for 24 hours. Graff called on club women to use their influence to abolish the use of the ice pack and install “a system of instruction and discipline that will aid in building women for the state of California.”

Looking for a fresh image, the name California School for Girls was legally changed to the Ventura School for Girls in 1925. From the inception of the juvenile court in 1903, judges retained the option of committing youth to the state institutions. But the three state schools were expensive. In 1923 it cost over three times more to keep a girl at the Ventura school than it did to house an inmate at San Quentin. Despite attempts to upgrade facilities and improve management, all three juvenile institutions were regular subjects of controversy. By the end of the 1930s, many Californians were anxious for reform.

New Agency Promises New Approach

In 1941 the legislature created the California Youth Authority (CYA), touting a new model of juvenile justice based on rehabilitation instead of punishment. The new agency was to centralize the management of the juvenile institutions which officials believed would bring an end to the decades of scandals and abuse. But as California’s population grew after World War II, so did the population at the state institutions. Conditions deteriorated and new rehabilitation techniques could not change the institutional culture of violence, deprivation, and alienation.

By the 1950s the Ventura School for Girls was overcrowded and falling apart. The once model cottages were found to be inadequate and beyond repair. With no space at the school, many girls were kept in county jails and juvenile halls. The cottages also didn’t allow for the proper segregation of older girls and more serious problem cases. A new school was designed to hold as many as 350 girls and a site was selected in Camarillo. On July 18, 1962, the school moved from its original site on Ventura Avenue.

Over the decades, the number of youths committed to CYA institutions would vary, primarily depending on the mood of the voters. From the mid-60s to the mid-70s, counties expanded local probation services, and reduced their reliance on the state institutions. In 1970, a change in the law resulted in fewer female commitments and Ventura School for Girls became co-educational. In the 1980s, voters became more conservative, and more juveniles were committed to state institutions. At its peak in 1996, 10,000 boys and girls were held in 11 state-run facilities. California had the nation’s third highest youth incarceration rate. In response, the state legislature imposed a financial penalty on counties that committed youth to the CYA for minor delinquent acts. Within a year the population at the institutions began to decline. In 2000, voters approved Proposition 21 a “get tough” measure which allowed juveniles accused of certain violent and serious offenses to be tried in adult court without the permission of the juvenile court.

In the early 2000s, the state Inspector General issued several critical reports describing the CYA as a “system in chaos that provided ineffective services in a poorly managed and highly punitive prison-like environment.” In November 2004 the Farrell consent decree was filed with the court. The decade-long, court-supervised agreement was the result of a class action lawsuit which contended that the CYA was little more than a poorly managed youth prison where children were exposed to high levels of routine violence with no meaningful rehabilitative services. A team of youth corrections experts hired to make recommendations to the state concluded it was “a system that is broken almost everywhere you look”. The state agreed to fix the problem by eliminating the institutional structure of training schools and replacing it with a modern system designed to be rehabilitative. The state’s remedial plan included the creation of small, therapeutic living units. But the state made little progress in achieving the promised reforms.

Realignment and the Shift Away from State Institutions

In 2011 the legislature approved funding in support of the idea of “realignment.” Counties would drastically cut back on commitments to the state institutions and use the state money to support local facilities and residential placement. The financial incentives worked. Within a decade, California had only 750 youth in state institutions and one of the nation’s lowest youth incarceration rates. While operating at a fraction of its capacity, the system was still extraordinarily expensive costing $200 million a year to operate. The cost per youth was more than $300,000 a year.

In 2020, Governor Gavin Newsom signed Senate Bill 823 which required the state’s 58 counties to designate a local facility for the incarceration of juveniles. The bill stopped counties from sending youths to the state facilities after July 2021 which are now scheduled to be shut down at the end of June 2023. The Ventura School for Girls was renamed the Ventura Youth Correctional Facility and is still the only state-run facility with both male and female youths. As preparations were being made for its closure, a report by the 2020-2021 Ventura County Grand Jury noted that no funds had been allocated for major repairs. They found the grounds reflected the age of the facility and showed a lack of maintenance. Many of the buildings had roofs leaks and were covered with tarps. The walkways were cracked and lifted in many places.

Make History!

Support The Museum of Ventura County!

Membership

Join the Museum and you, your family, and guests will enjoy all the special benefits that make being a member of the Museum of Ventura County so worthwhile.

Support

Your donation will help support our online initiatives, keep exhibitions open and evolving, protect collections, and support education programs.

Bibliography

- “After the Doors Were Locked: A History of Youth Corrections in California and the Origins of Twenty-First Century Reform: Macallair, Daniel E., Shelden, Randall G.: 9781442246713: Amazon.com: Books.” Amazon.com. Spend Less. Smile More. Accessed February 7, 2023. https://www.amazon.com/After-Doors-Were-Locked-Twenty-First/dp/1442246715

- “An analysis of direct adult criminal court filing 2003-2009: What has been the effect of Proposition 21?” Center on Juvenile and Criminal Justice — Home. Accessed February 7, 2023. https://www.cjcj.org/uploads/cjcj/documents/What_has_been_the_effect_of_Prop_21.pdf

- “Annual Inspection of Public Prisons.” 2020 – 2021 Ventura County Grand Jury. Accessed February 7, 2023. https://vcportal.ventura.org/GDJ/docs/reports/2020-21/GJ-Report_2020-21_AnnualInspectionOfPublicPrisons.pdf

- “California Plans to Close Troubled Youth Prisons After 80 Years. But What Comes Next?” Los Angeles Times. Last modified February 15, 2021. https://www.latimes.com/california/story/2021-02-15/california-youth-prisons-closing-criminal-justice-reform

- “California Youth Authority.” SAGE Publications Inc. Accessed February 7, 2023. https://us.sagepub.com/sites/default/files/upm-assets/2791_book_item_2791.pdf

- “Changes to California’s Youth Prison System Prove Difficult to Implement.” EdSource. Accessed February 7, 2023. https://edsource.org/2021/changes-to-californias-youth-prison-system-prove-difficult-to-implement/661967

- “The Forgotten Girls: the Ventura School for Girls, 1913-1962.” One Moment, Please… Accessed February 7, 2023. https://www.socalstudio.org/downloads/proofs4.pdf

- Graf, Gladys. “Ventura School for Girls Hit in Expose!” Los Angeles Examiner, January 15, 1923, 1.

- “Historian Lillian Faderman Follows the Long-Winding Road of Liberation in “Woman”.” Anisfield-Wolf Book Awards. Accessed February 7, 2023. https://www.anisfield-wolf.org/2022/03/faderman-woman-review/

- “The History of the Division of Juvenile Justice.” Division of Juvenile Justice. Last modified April 18, 2022. https://www.cdcr.ca.gov/juvenile-justice/history/

- “Intelligence Testing at Whittier School, 1890–1920.” Department of Chicana and Chicano Studies – UC Santa Barbara. Accessed February 7, 2023. https://www.chicst.ucsb.edu/sites/secure.lsit.ucsb.edu.chic.d7/files/sitefiles/people/chavez-garcia/ChaveGarciaPHR.pdf

- “A Look Back In Time – Fred C. Nelles School.” Fred C. Nelles School – California State Historical Landmark: Number 947. Accessed February 7, 2023. https://fredcnelles.com/history/a-look-back-in-time/

- Los Angeles Herald. “Ventura School Head Officially Out; Name Successor.” May 27, 1919.

- The Los Angeles Times. “Girls Plotted to Burn Whole School, Escape.” March 2, 1921.

- The Los Angeles Times. “News Brief.” August 20, 1914.

- The Los Angeles Times. “Rush Whittier Guards to Quell Girl Mutiny.” March 1, 1921.

- The Los Angeles Times. “School Seeks Investigation.” December 11, 1918.

- The Los Angeles Times. “School for Girls Taken to Ventura.” July 4, 1916.

- The Los Angeles Times. “Tell of Ice to Cure Bad Girls.” January 16, 1919.

- Martin, Philo J. “Construction is Rapidly Going On.” Ventura Free Press, January 8, 1915.

- The Marysville Appeal (Marysville, CA). “Some of the State’s Expenses Recited by Geo. Radcliff.” August 30, 1923.

- “Opinion: Closing California’s State Youth Prisons is a Victory for Racial Justice.” Juvenile Justice Information Exchange. Last modified December 30, 2021. https://jjie.org/2020/10/19/closing-californias-state-youth-prisons-is-a-victory-for-racial-justice/

- Oxnard Press Courier. “Girls School Seeks Nyland Acres Site.” May 13, 1952.

- Oxnard Press Courier. “Girls Reform School Would House Near 350.” May 14, 1952.

- “Renewing Juvenile Justice.” ERIC – Education Resources Information Center. Accessed February 7, 2023. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED537791.pdf

- “Unmet Promises: Continued Violence & Neglect in California’s Division of Juvenile Justice.” Center on Juvenile and Criminal Justice — Home. Accessed February 7, 2023. https://www.cjcj.org/uploads/cjcj/documents/unmet_promises_continued_violence_and_neglect_in_california_division_of_juvenile_justice.pdf

- Ventura Daily Free Press. “An Explanation of State School Affairs.” February 28, 1921.

- Ventura Daily Free Press. “Mrs. Weymann Makes Recommendations.” January 18, 1919.

- Ventura Daily Free Press. “State School Girls Riot Twenty Five In Jail.” February 28, 1921.

- Ventura Daily Free Press. “State School Hearing is Concluded Today.” January 18, 1919.

- Ventura Daily Free Press. “The Other Side Heard in Investigation at School.” January 17, 1919.

- Ventura Free Press Weekly. “New Building at State School For Girls Dedicated Saturday Before Large Number of Prominent State Officials and Citizens.” April 16, 1920.

- Ventura Free Press. “First School Managed Wholly by Women.” January 16, 1914.

- Ventura Free Press. “Girls State School.” November 27, 1914.

- Ventura Free Press. “Good Work State School.” March 27, 1914.

- Ventura Free Press. “Mrs. Foster Named Trustee of Ventura Girls’ School.” January 9, 1914.

- Ventura Free Press. “No Authority at State School.” March 2, 1921.

- Ventura Free Press. “School Quiet After Storm Girls Back to Normal.” March 2, 1921.

- Ventura Free Press. “State Girls’ School is Assured for This City.” December 26, 1913.

- Ventura Free Press. “State Industrial School to be Located in Ventura.” December 12, 1913.

- Ventura Free Press. “State School Soon Under Way.” April 25, 1914.

- Ventura Free Press. “State School Will Solve Delinquent Girl Problem.” January 30, 1914.

- Ventura Free Press. “Trustees of Girls’ School Consider Building Plans.” March 13, 1914.

- “Woman’s Club Movement in the United States.” Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia. Last modified February 8, 2023. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Woman%27s_club_movement_in_the_United_States

- “The Women Citizen Vol.1-3 (Feb.-Oct. 1912-1913) : Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming : Internet Archive.” Internet Archive. Accessed February 7, 2023. https://archive.org/details/womencitizen1912unse/page/n67/mode/2up