By Museum Volunteer Andy Ludlum

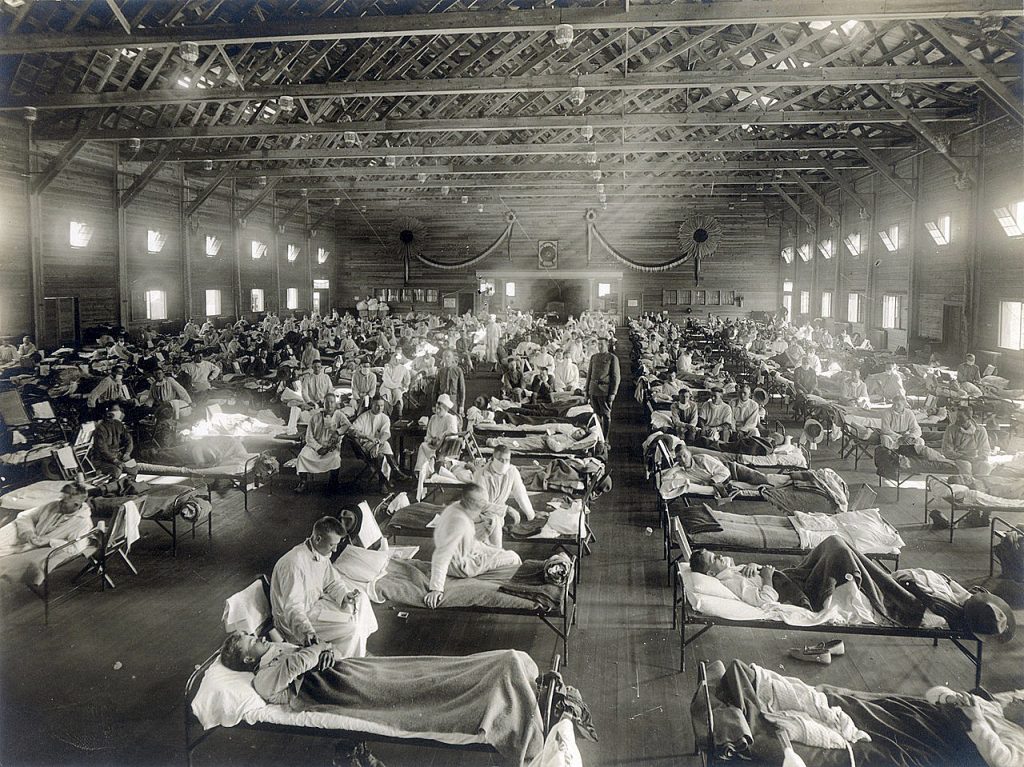

In March 1918, an Army cook named Albert Gitchell was hospitalized with a 104-degree fever at Camp Funston in Fort Riley, Kansas. Gitchell was one of the first documented cases of the influenza that would quickly spread through the camp, home to 54,000 soldiers about to be deployed to Europe. By then, the U.S. had been at war for nearly a year.

This was the start of the pandemic which would last for two years and infect about one-third of the planet’s population. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates 50 million people died in the pandemic, including 675,000 Americans.

There were three waves of influenza. The virus mutated after it was spread throughout Europe by wartime troop movements. In August, ships departing Plymouth, England were carrying troops infected with this new, far deadlier strain of the virus. As these ships arrived in U.S. port cities, the second wave of the pandemic began. It was during the brutal fall of 1918 that Ventura County was first exposed to the virus.

Ventura County today faces many of the same challenges its residents had to deal with in 1918. In early May 2020, the city of Oxnard surpassed Simi Valley as having the largest number of Covid-19 cases in the county. There is a detailed day-to-day record in the Oxnard Daily Courier of how the city responded to a similar crisis during the 1918 pandemic.

Oxnard Among the First Cities to Close

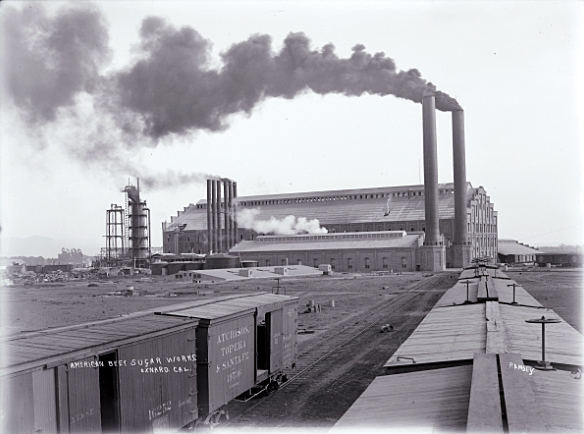

PNgp453, MVC Library & Archives collection.

On October 14, 1918 it was reported there were 200 cases in Oxnard. Influenza was on every block in the city and few families had escaped infection. The most serious outbreak: 80 men at the American Beet Sugar factory were stricken in one day. Two days later, on October 16, the city trustees (city council) ordered Health Officer Dr. G. A. Broughton to “close theaters, motion picture houses, schools, churches, both public and private dances and all public gatherings until further notice.” Some “essential” places of business remained open.

The trustees also ordered that every house with an influenza patient be “placarded.” Signs were posted on the house and the address was printed in the newspaper so that “callers may not unnecessarily expose themselves to the disease.” It was later explained that placards did not mean the quarantine should interfere with the “necessary and legitimate business of the occupants of the house.” A part-time city mail carrier was appointed by the police chief to count the active cases and post the placards on the houses. Doctors were asked to report every case to the health officer.

Oxnard was among the first California cities to close. Los Angeles had closed five days earlier, San Francisco would close two days after Oxnard. Ventura waited another week before closing its businesses and schools.

The State Board of Health considered closing schools as a last resort, claiming that students would be safer in school than just “running free on the streets.” One Oxnard trustee, a school principal, opposed the idea of closing the schools, but was outvoted. He did get the trustees to order children to stay home. Playing outside was prohibited. The police chief was ordered to add a couple of men to patrol the residential districts and question any children on the streets. If they were not out on a legitimate errand, they were sent home.

Oxnard city firemen washed the pavement and sidewalks of Fifth Street and Saviers Road. They started at 9 in the evening and worked until 5 in the morning. The washing was done at the request of the trustees as a precautionary health measure to insure “every bit of germ laden dust” in the streets, gutters and sidewalks had been washed off. Oxnard officials later would cite washing the “influenza germs out of the atmosphere” as one of the key reasons the city fared better than neighboring Ventura.

It fell to local political and health officials to improvise a plan to safeguard the public. There was no significant county, state, or federal coordination. The actions taken varied from city to city, even within Ventura County. Many of the “social distancing” measures used today were known and implemented in 1918. But, like today, some people chose to ignore the advice of the health experts.

Doctors had never seen anything like this influenza. It could kill a perfectly healthy young man or woman within 24 hours of first showing symptoms. Their skin would turn blue and their lungs filled with fluid, causing them to suffocate. The scientists had no idea what caused it. Microscopes of the time could not see anything as small as the influenza virus, which would not be discovered until the 1930s. There was no flu vaccine until the early 1940s.

Many medical professionals in 1918 believed that the flu was caused by a bacterium commonly known as Pfeiffer’s bacillus. In February 1919, Navy doctors on Goat Island (now Yerba Buena Island) in San Francisco Bay deliberately tried to infect 50 young sailors with influenza. The volunteers were given “jars of flu germs which they breathed into their lungs, they had flu germs injected into their bodies.” Not one of them became infected, because the “flu germs” they had been given were Pfeiffer’s bacillus. Ultimately, the pursuit of a bacterial cause of influenza distracted medical researchers and cost the nation millions of dollars to develop ineffective testing and treatment techniques.

Living with the Virus

“It touched my family and we were all sick, all sick. And my mother got pneumonia besides that, but we were ok. Nobody died. Very fortunate because there was another family that used to be real good friends of ours. There was ten of them and all died. I couldn’t believe it, and my father was very scared because my mother got pneumonia, you know, and that’s very scary.”

– Maria Sanchez Rios who lived in Fillmore at the time of the 1918 outbreak.

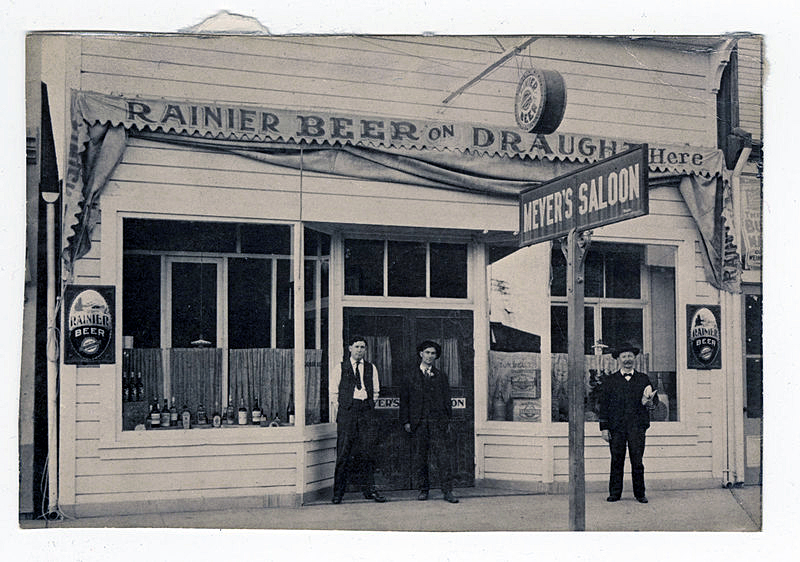

at 527 Saviers Road in Oxnard.

PN40677 MVC Library & Archives collection.

Oxnard’s first flu fatality, 39-year-old Charles Webb was reported on October 24, 1918.

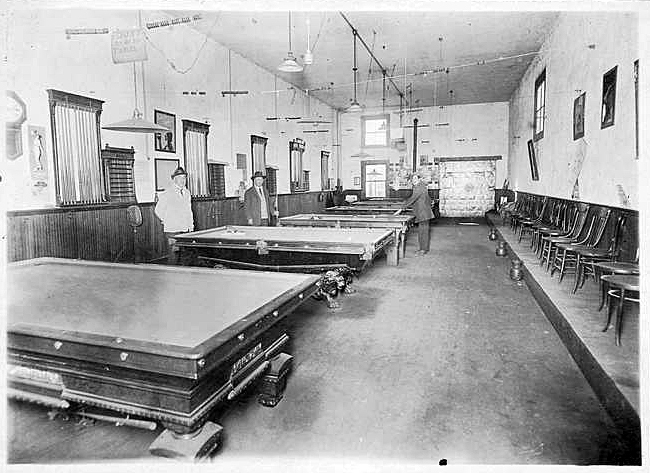

Life had changed dramatically for the people of Oxnard. All meetings, parties and social engagements were banned. Memorial services were postponed. Benches and chairs were removed from the Saviers Road pool rooms and in the downtown business district to discourage gatherings.

M. G. Walker ran the Oxnard laundry. When he and five of his employees were unable to work after coming down with the flu, Mrs. Walker had to work “night and day.” While she reportedly had things “running fairly smooth,” she asked for understanding as some laundry would not be washed by the next delivery time. By October 23rd, Roy Palmer of 361 1st Street had the dubious distinction of having more sick people in his home than in any other house in the county. Roy, his wife, his parents, his three kids and a visiting sister all had the flu.

Most people were treated at home since the hospital filled up quickly. After announcing three days earlier that it would care for influenza patients, St. John’s Hospital in Oxnard already had 23 cases by October 28th.

December 19, 1918.

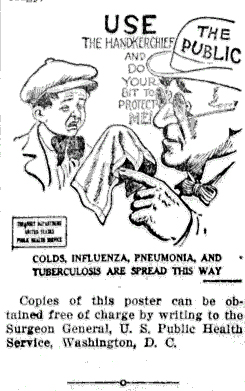

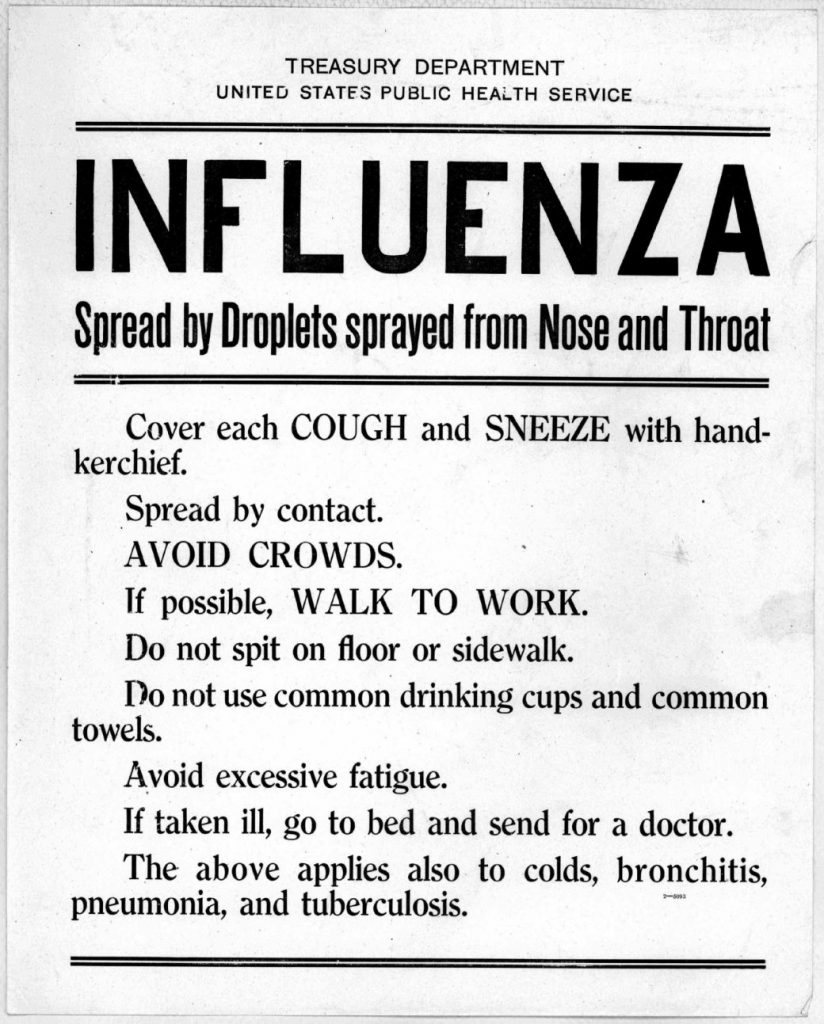

Doctors offered common-sense advice. People were told to avoid crowded places and to cover their mouth and nose with a handkerchief when coughing or sneezing. There were educational programs about the dangers of coughing and sneezing and the careless disposal of “nasal discharges.” People were urged to go to bed as soon as they felt sick and to call the doctor.

Home remedies included eating cinnamon, drinking wine, or drinking a beef broth called Oxo’s meat drink. Dr. Mark D. Smith promoted a preventative gargle of 1 teaspoon of baking soda, one-half teaspoon of table salt, 2 tablespoons of Listerine, 10 drops of eucalyptus oil and 2 tablespoons of sterile water. A teaspoon of this mixture was mixed with hot water and gargled.

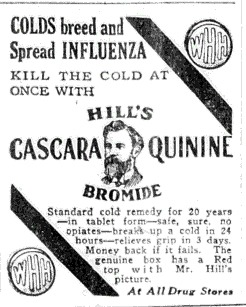

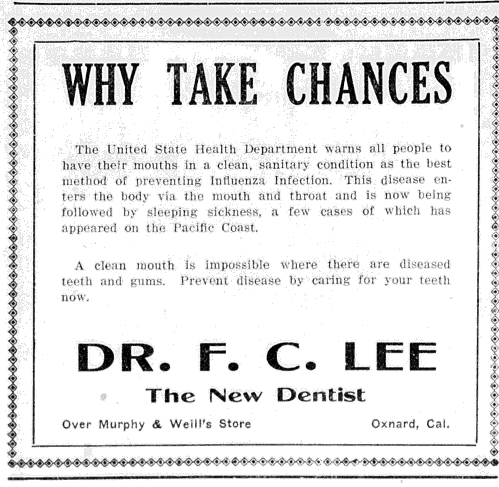

At the drug store there was Begy’s Mustarine, a hot, yellow mustard-based product to be rubbed on the throat and chest. Hills Bromide Cascara Quinine, containing “no opiates,” promised to kill colds in 24 hours or your money back. An Oxnard dentist repeated a warning from the United States Health Department that having your mouth in a clean sanitary condition was the best way to prevent influenza infection.

Some doctors recommended a post-meal spray of quinine bifulsate, an anti-malaria drug, which was thought to “preclude much danger from the malady.” There is no evidence quinine was effective in preventing or treating influenza.

By 1918 thousands of acres of lemon trees had been planted in Oxnard. The Los Angeles Times reported The California Fruit Growers’ Exchange had published pamphlets boasting that sucking on a lemon could prevent the flu. One reader couldn’t resist responding, “we can judiciously make use of lemons, in cold and hot beverages, in different salads, on fish, stews, pies without going to extremes in making monkeys of ourselves by attending to weddings, funerals, sermons and concerts with lemons in our mouths.”

Nursing Shortage

“They made the Men’s Club in Ojai into a hospital…Poor old Dr. Sager was the only doctor in town and he was just worked to death. Of course, there were four or five in our family that were home in bed with the flu…and Dick was too sick and they had him over there because he had pneumonia…It was really bad. We lost a lot of people during that flu epidemic.”

– Hortence Clark Bauer who lost her brother Dick to influenza

There was a nationwide shortage of professional nurses in 1918. Thousands of nurses had been deployed as part of the war effort. The shortage was made worse by the American Red Cross’s refusal to train African American nurses until the pandemic had mostly passed. Because outbreaks continued into the 1920s, there are examples of African American women nursing Oxnard influenza patients.

In the late fall, there was an urgent call for nurses to help care for the sick in their homes in Oxnard. Only nine home-care nurses were available, and they were “nearly worn out with work.” The newspaper appeal said both men and women were needed; “men to remain on watch at night so that the nurses can get some rest.” Within a week, the newspaper printed the names of 19 women and one man who could be “called on directly by persons needing them.” Among them was 78-year-old Margaret Morey who had already nursed two influenza cases.

Besides the physically and emotionally demanding work, nurses of the time were exposed to potentially toxic chemicals. It was common to use a highly diluted mixture of bichloride of mercury for hand sanitation. This compound of mercury and chlorine was used to treat syphilis. It is no longer in use today because of the danger of mercury poisoning. Newspaper articles of the period often reported accidental deaths and suicides from mercury bichloride.

Obey the Laws and Wear the Gauze

“The wearing of masks is advised and is seriously to be urged as a matter of compulsion. Certainly, they should be worn in proximity to known cases, and in crowds. It is becoming an interesting world to live in, isn’t it?”

– Flora H. L. Henderson, writing in the Santa Barbara News, October 30, 1918

The use of masks was as controversial in 1918 as it is today. The U.S. Surgeon General had questioned the usefulness of masks. A San Diego newspaper editorial suggested they were better suited for “highwaymen, burglars and holdup men” and expressed the regret “that some of the young women in public employment are compelled to wear these masks. We miss their pretty faces.”

Some cities like Oxnard rejected masks. But Ventura and San Francisco enforced mandatory mask laws with stiff fines. The Courier described Ventura’s mask law a way of “separating people from their money.” Fines of $5 ($94 today) were imposed on people caught in public without a mask. San Francisco’s Board of Health encouraged songs to be written about mask wearing, including one that featured the lyrics: “Obey the laws and wear the gauze. Protect your jaws from septic paws.” The Courier questioned a select group of county doctors, none of whom enthusiastically supported mask wearing. At best they saw them as a benefit around the sick, but unnecessary on the street. When San Francisco reopened on November 21, 1918, a whistle sounded at noon across the city and many people ripped off their masks and threw them into the streets.

Oxnard Takes More Drastic Measures

– Flora H. L. Henderson, writing in the Santa Barbara News, October 30, 1918

“The American people are careless. Despite all the injunctions they have received to be on guard against acquiring or disseminating the “influenza”, many are going about disregarding these and decrying their need. I do not doubt that hundreds of them are of the same mind of two tradesmen who came to my house yesterday…both of whom asked me idly what I thought of the disease, remarking for themselves that they thought ‘altogether too much was being made of it…’ Neither of them wore a mask or took any precaution against contracting or disseminating the contagion. And I have heard within the hour that the wife of one of these was carried to the hospital this morning.”

While not wanting to create a “state of hysteria,” Dr. Broughton warned on October 31 that Oxnard had as many, if not more, flu cases than at any other time during the epidemic. Many had died, others were critically ill.

He said the flu needed to be “regarded with greater seriousness” or more drastic measures would have to be taken. Broughton said, “We have already closed churches, schools and moving pictures. We have made recommendations to the more inessential places of business or pleasure, but such measures, even when faithfully carried out, have proven inadequate and ineffective.”

The next day, the trustees instructed the city marshal to close every saloon in the city. Pool and billiard halls and soda fountains were also closed. Their order said, “only places where the necessities of life are sold should be allowed to remain open.” Liquor could still be purchased in packages from wholesalers.

PN9316 MVC Library & Archives collection.

The people of the city were asked not to go out any more than they were “obliged to” and spend “the least possible time in the transaction of their business.” Again, doctors were requested to report cases and keep their influenza patients quarantined at home. Still, the death toll increased daily.

On November 2nd, it was reported that a popular young man, 20-year-old John “Chumpy” Petrou had died of pneumonia following influenza. He had become ill the week before while working for the Dunn Manufacturing Company where he had been employed for only a day and a half. He did not “take to his bed at once,” his system became weakened and the fatal pneumonia developed.

The flu pandemic did have an impact on the November 1918 election. Turnout in Oxnard was noticeably light. As of 1:00 p.m. on November 5, only a quarter of the registered voters had cast ballots. The Courier said, “every other family seem to have it [flu] – interferes with those who wish to vote and makes it impossible for those who have it to vote.” The paper received news over telephone that only 50% of the total vote was expected to be cast in Los Angeles.

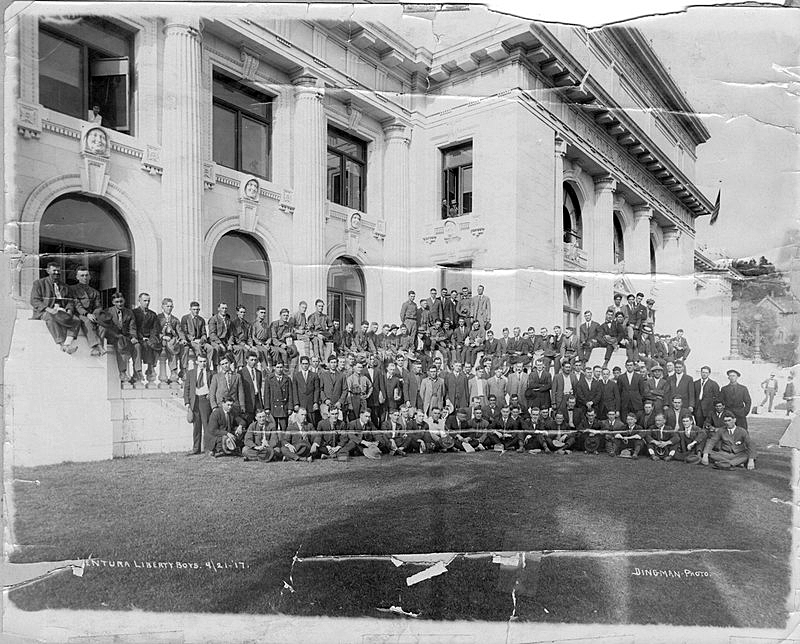

PN40659 MVC Library & Archives collection

Just after election day, Oxnard suffered another blow. The beloved pastor of the Santa Clara Church, the Rev. Fr. John S. Laubacher, died in his home. He had become sick from influenza only a week before and after three days he developed pneumonia. As his condition became more critical, he was delirious and finally unconscious. Doctors tried unsuccessfully to keep the 49-year-old priest alive with oxygen. Father Laubacher had opened St. John’s Hospital and Medical Center in 1914.

Dr. Broughton was growing increasingly concerned about a resurgence of the flu. While conditions in the city were improving, he feared not enough care was being taken in rural communities around Oxnard. He said, there was “too much visiting in the rural sections and in the small-town stores,” adding that “the country folk do not seem to take it seriously enough when they are taken ill.”

Oxnard Lets Down Its Guard

“Half the population of the city was downtown to see the excitement. A great many of them came with cow bells, cans and kettles or anything that would make a noise. An impromptu procession was formed on Fifth Street, headed by military reserve musicians, men women and children fell into a line several blocks long…The big crowds remained until nearly 10:00 p.m.”

– Oxnard Daily Courier, November 12, 1918

The armistice signed on November 11, 1918 marked a victory for the Allies and a defeat for Germany. The end of World War I may have enabled a resurgence of influenza in Oxnard as joyous citizens ignored precautions and celebrated in the streets.

A young Hueneme man became the first local soldier to return home in January 1919.

PN2854 MVC Library & Archives collection.

By November 20, Oxnard was ready to reopen. “The ban is off. And everyone is happy again,” led the headline story in the Courier. Schools were in session for the first time in five weeks. Businesses reopened including the cigar stores, pool and billiard rooms, saloons, and fountains. The library and movie theaters opened the next day. Theaters delayed opening a day because they did not have films on hand. Churches held services on Sunday to begin Thanksgiving week. Dr. Broughton warned there were still some cases of influenza in the city and, despite the best precautions, new ones would develop. He still recommended people “refrain from congregating needlessly.”

San Francisco had reopened four days earlier and by November 21 ended its mask law. Santa Barbara was still closed. Dr. Broughton was aware the virus was still a threat in neighboring Ventura and could easily spread to Oxnard again. Ventura and Los Angeles would not end their closures until early December.

By now Oxnard was being touted for its apparent success in dealing with the outbreak. Dr. Broughton said his counterpart in Santa Barbara had called him to “learn the methods practiced here to keep down the plague.” He had calls from other towns as well, as “the fame of Oxnard’s successful handling of the epidemic” had “spread far and wide.”

Response Marred by Discrimination

There was an ugly side to Oxnard’s flu response. The treatment of ill Mexican workers was separate and, in many cases, sub-standard. City officials complained to Ventura County Supervisors alleging that ranchers were abandoning within city limits their workers who had become sick.

These abandoned workers had nowhere to go and no one to take care of them. City trustees instructed the town marshal to find a suitable place for the ill men on Saviers Road and to provide them with food and medicine, so they were not “loose spreading the disease.”

The Courier reported that one man was so sick he kept falling out of the chair in front of City Hall where he waited while the marshal tried to find a place for him. Rooming houses rejected the sick man. The marshal was told the county hospital was filled to overflowing and had only one nurse to take care of the patients. He finally found a place for the man for $25 a week ($425 today), including nursing care.

The city eventually opened a “temporary detention hospital” to care for ill, homeless Mexicans in the Donlon and Stewart building at the corner of Meta and Seventh streets. The marshal managed to scrape together cots and bedding and one woman, “not a trained nurse,” was hired.

When a group of citizens concerned for the treatment of non-white residents appeared before the trustees to ask for funding to care for those abandoned in the town, the Courier described them as a delegation of “better class Mexicans” who appeared before the trustees asking for an appropriation of $5 a day for a nurse at the hospital. Despite some discussion from the trustees that the city was doing nothing of the kind for “poor white people,” the trustees approved spending $5 a day to be used to pay two nurses $2.50 each.

Return to Normal May Have Come Too Soon

City life returned quickly to normal. In early December, The Knights of Columbus held their first meeting of the lodge since the flu ban lifted and a large crowd attended. Other communities also permitted large gatherings. Santa Barbara Elks held one of the biggest gatherings on December 14, bringing in hundreds of members from Santa Barbara, Ventura, and San Luis Obispo.

In mid-December, the U.S Health Service said the influenza was expected to lurk for months. Oxnard trustees were about to take more drastic steps in the enforcement of quarantine laws. Mayor Joseph Sailer wrote a personal letter to Oxnard doctors. He said it had been decided to establish “a strict quarantine over each case.” A special deputy was appointed to call doctors each day for a report of cases. Flu houses were still to be placarded, and families were advised that no one was to enter of leave the premises, except the breadwinner. The Mayor added if “means will permit…It will be the wish of the board of trustees that he resides apart from his home. If it is necessary for him to remain, then it will be expected of him that he will faithfully avoid any contact with the sick, not even going into the sick room.”

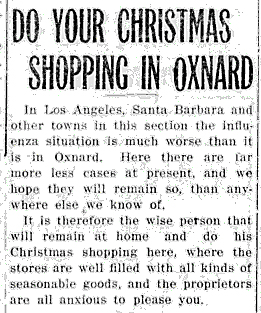

At the close of 1918, social distancing clearly did not apply to Christmas shopping. The Courier was running articles suggesting families do their Christmas shopping in Oxnard, pointing out the flu was much worse in competing Los Angeles and Santa Barbara.

The flu was disastrous to the economy in 1918. Businesses were forced to shut down or reduce production because so many of their employees were sick. In just one year, the average life expectancy of an American had dropped by a dozen years. A study by the Illinois Health News looked at the value of lives lost ($3000 adult, $500 child) and the cost of care for those who had recovered. They calculated the economic loss of these “vital assets” to be $1 billion. The authors contended health must be estimated in terms of dollars and cents “in order to reach the conscience of the average taxpayer who must…defray the expenses of local health departments.”

1919 Brings Another Wave of the Pandemic

The last evening of 1918 in Oxnard was “quietest in local history” from the standpoint of New Year’s Eve crowds. A young Hueneme man became the first local soldier to return home. For the first time in several months the Oxnard Opera House was crowded to capacity “indicating a return to…normal in health conditions.”

But the flu threat was still very real. The situation was dire in Santa Barbara. According to a letter printed by the Courier, “we are standing on our heads with work. The authorities are turning over residences to serve as hospitals, there being 2,000 cases in the city. Saturday morning there were 10 funerals at the Catholic Church.” On January 9, the city of Ventura closed for the second time. In Los Angeles, 680 new cases and 27 deaths were reported, prompting the heath officer to create more rigid quarantine rules. Despite the shocking numbers, the Los Angeles Auto Show opened its doors for over 12 hours on January 11. There was no suggestion to avoid crowds due to the flu.

On January 13, Dr. Broughton admitted Oxnard had let its guard down during the Christmas holidays with the relaxation of restrictions. While Oxnard had fared better than many other cities, Dr. Broughton was apprehensive. Twenty-one houses in the city were under quarantine for influenza. While not as large as during the fall wave, the number of cases was large enough to concern the health department and city trustees. They stopped short of ordering another closure. Instead, they opted for a new quarantine law. Its chief provision made it a punishable offense for any doctor or nurse to fail to report influenza cases immediately. Sometimes doctors had waited several days to report to the health department, delaying quarantine. Doctors and nurses failing to report promptly faced a $100 ($1,482 today) fine or ten days in jail.

On January 16, the virus was still not slowing in Ventura. The city had 24 new cases in a 24-hour period, and it would be another week before Ventura finally reopened. The number of cases in Oxnard continued to dwindle. On February 5th, a doctor proclaimed there was no influenza in the city, “the scourge has spent its force and was practically a thing of the past.”

Essentially, by the summer of 1919, the flu pandemic had come to an end, as those that were infected either died or developed immunity. Smaller flu outbreaks continued into the 1920’s in Ventura County, most notably in Oxnard. The last small outbreak subsided in March 1920.

By the 1920’s people had grown accustomed to living with the flu and were willing to debate some of the less weighty issues of the day, such as whether women’s clothing of the time, with its low cut tops and short skirts, was “largely responsible for the spread of the epidemic.” A noted French physician said just the opposite was true. He said “women’s dresses today permit a double aeration of the skin” which he considered healthful. “I do not believe colds are caught because of short skirts, for it is through the respiratory passages and not through the skin that one catches cold…. Besides, Eve, our grandmother, wore a costume more scanty than those of today and she never had influenza.”

Make History!

Support The Museum of Ventura County!

Membership

Join the Museum and you, your family, and guests will enjoy all the special benefits that make being a member of the Museum of Ventura County so worthwhile.

Support

Your donation will help support our online initiatives, keep exhibitions open and evolving, protect collections, and support education programs.

Bibliography

- “California Lessons from the 1918 Pandemic: San Francisco Dithered; Los Angeles Acted and Saved Lives.” Los Angeles Times. Last modified April 19, 2020. https://www.latimes.com/california/story/2020-04-19/coronavirus-lessons-from-great-1918-spanish-flu-pandemic?gclid=CjwKCAjwte71BRBCEiwAU_V9h1cqGUrPf07zhbogudRQBNVHSPSEm4aDdA706kNiupqXBjJZfLREHhoCwlAQAvD_BwE.

- “Coffins in a Bottle.” Science History Institute. Last modified April 18, 2019. https://www.sciencehistory.org/distillations/coffins-in-a-bottle.

- “Fact Check: Hydroxychloroquine is Not the Same as Quinine and Can’t Be Made at Home.” U.S. Last modified May 31, 2020. https://www.reuters.com/article/uk-factcheck-quinine/fact-check-hydroxychloroquine-is-not-the-same-as-quinine-and-cant-be-made-at-home-idUSKBN2370R9.

- French, Paul, or CNN. “In the 1918 Flu Pandemic, Not Wearing a Mask Was Illegal in Some Parts of America. What Changed?” CNN. Last modified April 5, 2020. https://www.cnn.com/2020/04/03/americas/flu-america-1918-masks-intl-hnk/index.html.

- “Spanish Flu: The Deadliest Pandemic in History.” Livescience.com. Last modified March 12, 2020. https://www.livescience.com/spanish-flu.html.

- History.com Editors. “Spanish Flu.” HISTORY. Last modified October 12, 2010. https://www.history.com/topics/world-war-i/1918-flu-pandemic.

- “How Some Cities ‘Flattened the Curve’ During the 1918 Flu Pandemic.” Last modified March 27, 2020. https://www.nationalgeographic.com/history/2020/03/how-cities-flattened-curve-1918-spanish-flu-pandemic-coronavirus/#close.

- “Malaria Drug Promoted by Trump Did Not Prevent Covid Infections, Study Finds.” The New York Times – Breaking News, World News & Multimedia. Last modified June 3, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/06/03/health/hydroxychloroquine-coronavirus-trump.html?referringSource=articleShare.

- Museum of Ventura County. “Oral History: Hortense Clark Bauer.” Recorded audio. February 1, 1988.

- Museum Ventura County. “Oral History: Maria Canchez Rios.” Recorded audio. October 21, 1999.

- Oxnard Daily Courier. “21 Cases of Flu; Caution Being Urged.” January 13, 1919.

- Oxnard Daily Courier. “Ban Is Lifted on Everything Except Schools in City.” November 20, 1918.

- Oxnard Daily Courier. “Ban Placed on Meetings of All Kinds.” October 18, 1918.

- Oxnard Daily Courier. “City Shut Tight as Ordered.” November 2, 1918.

- Oxnard Daily Courier. “City Will Pay $5 Per Day for Nurses.” November 13, 1918.

- Oxnard Daily Courier. “City of Ventura Closed.” January 9, 1919.

- Oxnard Daily Courier. “Close Tab on Influenza to be Kept.” October 18, 1918.

- Oxnard Daily Courier. “County Doctors Think Flu Mask of No Benefit.” December 5, 1918.

- Oxnard Daily Courier. “Disease Costs Billions a Year.” December 3, 1919.

- Oxnard Daily Courier. “Elks Meet Biggest in History.” December 11, 1918.

- Oxnard Daily Courier. “Firemen Make Clean City Streets.” November 4, 1918.

- Oxnard Daily Courier. “Flu Ban to Be Lifted Monday Next, Nov. 18.” November 13, 1918.

- Oxnard Daily Courier. “Flu Situation Bad in Santa Barbara.” January 6, 1919.

- Oxnard Daily Courier. “Flu Was Black Plague Years Ago.” October 30, 1918.

- Oxnard Daily Courier. “Flu Well in Hand in Oxnard.” November 27, 1918.

- Oxnard Daily Courier. “Flu and Lemons.” November 21, 1918.

- Oxnard Daily Courier. “Health Officer Warns Oxnard Citizens They Must Cooperate or Drastic Steps Will Be Taken.” October 31, 1918.

- Oxnard Daily Courier. “Help Wanted to Care for Influenza Sick.” November 15, 1919.

- Oxnard Daily Courier. “Here’s Why City Is Still Under Ban.” November 19, 1918.

- Oxnard Daily Courier. “High School Students Studying.” October 29, 1918.

- Oxnard Daily Courier. “Hueneme Boy First to Return Home After Licking Hun.” January 6, 1919.

- Oxnard Daily Courier. “Indigent Sick to Be Taken Care Of.” October 30, 1918.

- Oxnard Daily Courier. “Influenza Cases at a Standstill.” October 26, 1918.

- Oxnard Daily Courier. “Influenza Closes Schools and Movies.” October 16, 1918.

- Oxnard Daily Courier. “Influenza Coming back Doctors Say.” October 10, 1919.

- Oxnard Daily Courier. “Influenza Epidemic in Oxnard Subsiding.” March 10, 1919.

- Oxnard Daily Courier. “Influenza Hits Laundry Hard Blow.” October 18, 1918.

- Oxnard Daily Courier. “Influenza Keeps Half Voters Home.” November 5, 1918.

- Oxnard Daily Courier. “Influenza Status at County Seat.” November 21, 1918.

- Oxnard Daily Courier. “Influenza Test Made on 50 at Goat Island.” February 7, 1919.

- Oxnard Daily Courier. “Influenza at Ventura Still Bad.” January 16, 1919.

- Oxnard Daily Courier. Los Angeles Auto Show to Open on Saturday.” January 11, 1919.

- Oxnard Daily Courier. “Los Angeles Quarantine More Rigid.” January 10, 1919.

- Oxnard Daily Courier. “Los Angeles Quarantine More Rigid.” January 10, 1919.

- Oxnard Daily Courier. “Mayor Asks Physicians to Help Check Influenza Epidemic.” December 19, 1918.

- Oxnard Daily Courier. “Much Influenza, Few Cases Serious.” October 14, 1918.

- Oxnard Daily Courier. “New Year Greeted Very Quietly.” January 2, 1919.

- Oxnard Daily Courier. “No Gatherings for Another Week.” October 23, 1918.

- Oxnard Daily Courier. “No Influenza Here Says Doctor.” February 5, 1919.

- Oxnard Daily Courier. “Oxnarders Celebrate Peace in Joyous Riot.” November 12, 1918.

- Oxnard Daily Courier. “Quarantine to Be More Strict Here.” December 11, 1918.

- Oxnard Daily Courier. “Quick Influx of Influenza Cases to Hospital.” October 28, 1918.

- Oxnard Daily Courier. “Rev. Fr. Laubacher Victim of Dread Spanish Influenza.” November 6, 1918.

- Oxnard Daily Courier. “Sad Death of Bright Young Man.” November 1, 1918.

- Oxnard Daily Courier. “Schools Open Next Monday.” November 15, 1918.

- Oxnard Daily Courier. “Sees Flu Conditions Improve.” November 5, 1918.

- Oxnard Daily Courier. “Temporary Hospital Opened.” November 4, 1918.

- Oxnard Daily Courier. “Trustees Close All Saloons, Cigar Stores, Fountains.” November 1, 1918.

- Oxnard Daily Courier. “Trustees Will Adopt Strick Flu Ordinance.” January 15, 1919.

- Oxnard Daily Courier. “Ventura Reopened.” January 23, 1919.

- Oxnard Daily Courier. “Water for the Flu Germ.” April 18, 1919.

- Roos, Dave. “Why the Second Wave of the 1918 Spanish Flu Was So Deadly.” HISTORY. Last modified March 3, 2020. https://www.history.com/news/spanish-flu-second-wave-resurgence.