By Andy Ludlum, Museum Volunteer

Early Ventura County newspapers offered one of the few ways to connect pioneer communities with stories, opinions, and news of the day. The first newspapers in Ventura County were all closely identified with political parties and had unyielding editors who loved to rile up the community and often teetered on the edge of libel. None of them were shy about picking a fight with City Hall or, better yet, with each other. One editor was even beaten by the unhappy subject of one of his harangues.

Since the first Ventura newspaper was printed in 1871 there have been more than 80 in the county. Most of them were short-lived. One paper put out a single edition. Two or three lasted only weeks. There was a monthly and even one yearly newspaper. Most were only noticed with short obits when they died.

Ventura’s First Newspaper Supported Breaking Up Santa Barbara County

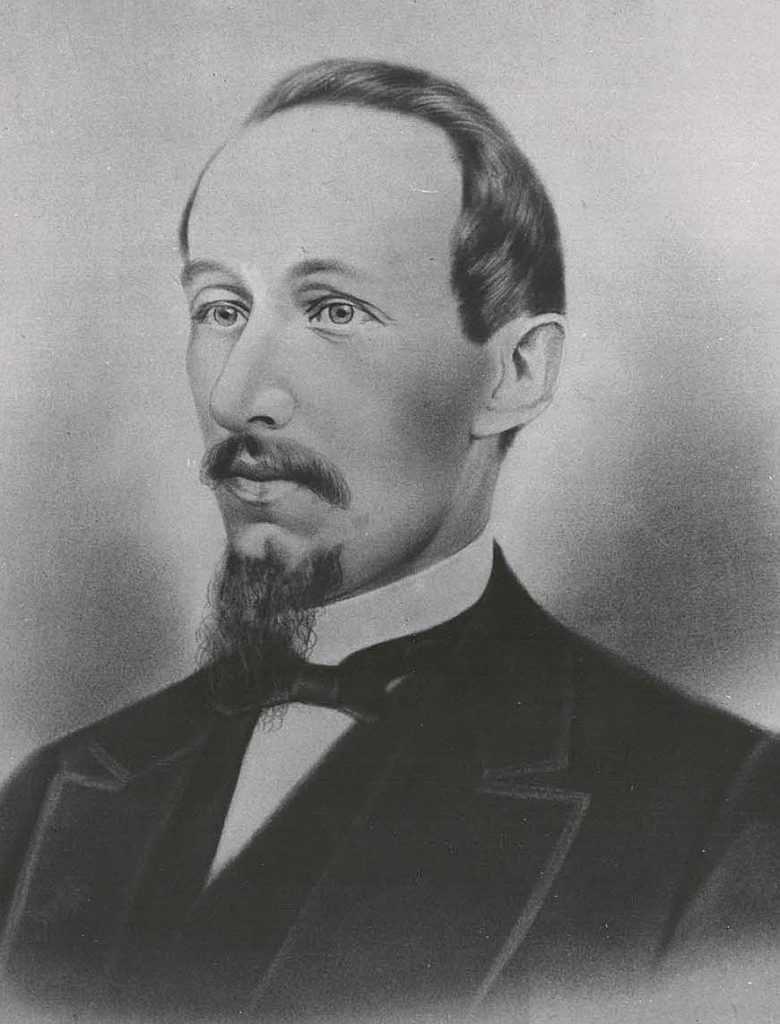

The county’s first newspaper, The Ventura Signal, was established by John Harden Bradley and began publishing in April 1871. It had 200 readers. Bradley had done many things in his short life. He’d been a miner, surveyor, schoolteacher, justice of the peace and real estate salesman.

In 1869 Bradley worked for a Santa Barbara newspaper, drumming up new subscribers in Ventura, which was then part of Santa Barbara County. In March of 1871, Santa Barbara Press editor J. A. Johnson reported Bradley had “gone to San Buena Ventura to try to start a newspaper” but cautioned him it was “a somewhat expensive business” and it was “much easier to start a newspaper than to run it a year after the start.”

A few months later, the Santa Barbara Press said it had “armed the editor and chief (Johnson) with three Henry rifles and a 32-pounder (cannon) to go to Los Angeles.” Bradley saw his chance to take a shot at the Santa Barbara paper. On November 4, 1871 he wrote, “He had no such weapons when he passed here. Don’t you mean three pint-flasks and a jug?”

Bradley’s Signal was a strong advocate of splitting Santa Barbara County in two, which happened in early 1873 with the creation of Ventura County. Bradley contracted tuberculosis and his health forced him to sell the paper in June 1873; he died later that year at the age of 31. After Bradley’s death, John Sheridan and W.E. Shepherd took over as publishers of the Signal. Shepherd and Sheridan were publishers of the Signal in November of 1875 when the Ventura County Republicans began an effort to start a rival paper.

Politics Sparks Ventura County’s Second Newspaper

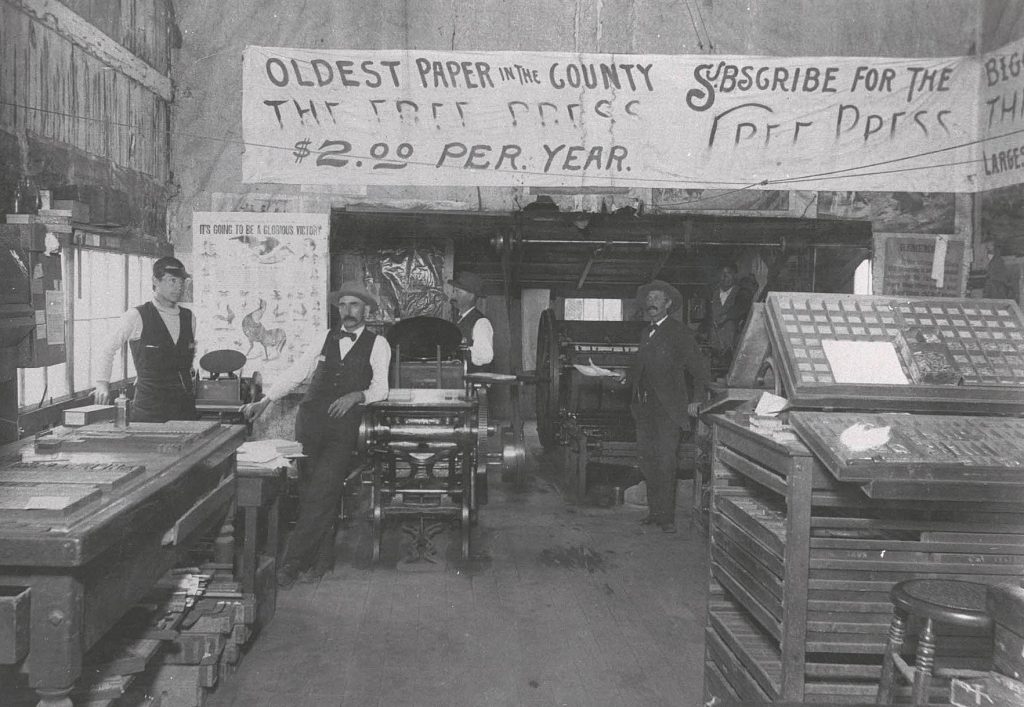

The Ventura Free Press debuted as a staunchly Republican paper under Oliver P. Hoddy. Hoddy was a transplant from Calistoga who arrived in San Buenaventura with his printing press. The county’s first daily, Hoddy boldly promised in his first edition on November 14th that he “was willing to be judged not by our promises but by our performances.” But after just eight weeks the fledgling Free Press changed to a weekly.

Competitors, near and far, were brutal. The Oakland Tribune wrote, “It was sprightly in its lifetime, but was brought forth too soon, hence the tears.” The Santa Monica Outlook said, “Perhaps our neighbor’s misfortune may find an explanation in the fact that he has been more zealous in his attempts to establish the defects of others than in supplying the remedy to his own.” In the Signal E.W. Sheridan tried to shovel the last bit of dirt on what he hoped was the grave of his competitor: “The little local daily, though dead, kicketh weakly. Every seven days it gives a convulsive little gasp and kick. By and by it will quit gasping and will be buried.”

Hoddy’s Free Press survived, despite his uncanny ability to alienate almost everyone. Shepherd wrote in the Signal “The new paper (ran) a whole column of electrotyped vinegar bitters” in its first issue. He called the Free Press “a daily with a makeup that would have disgraced a country newspaper 25 years ago, a daily filled with old and battered stereotypes of patent medicine.”

Shepherd would eventually sell his interest in the Signal to go into politics. John Sheridan decided to return to Missouri and his brothers Edwin and Solomon took over the paper. In 1881, Sol sold out to his brother Ed. Later, Ed Sheridan would play a key role in creating a third competitor for the Signal.

A Controversial Preacher Takes Over

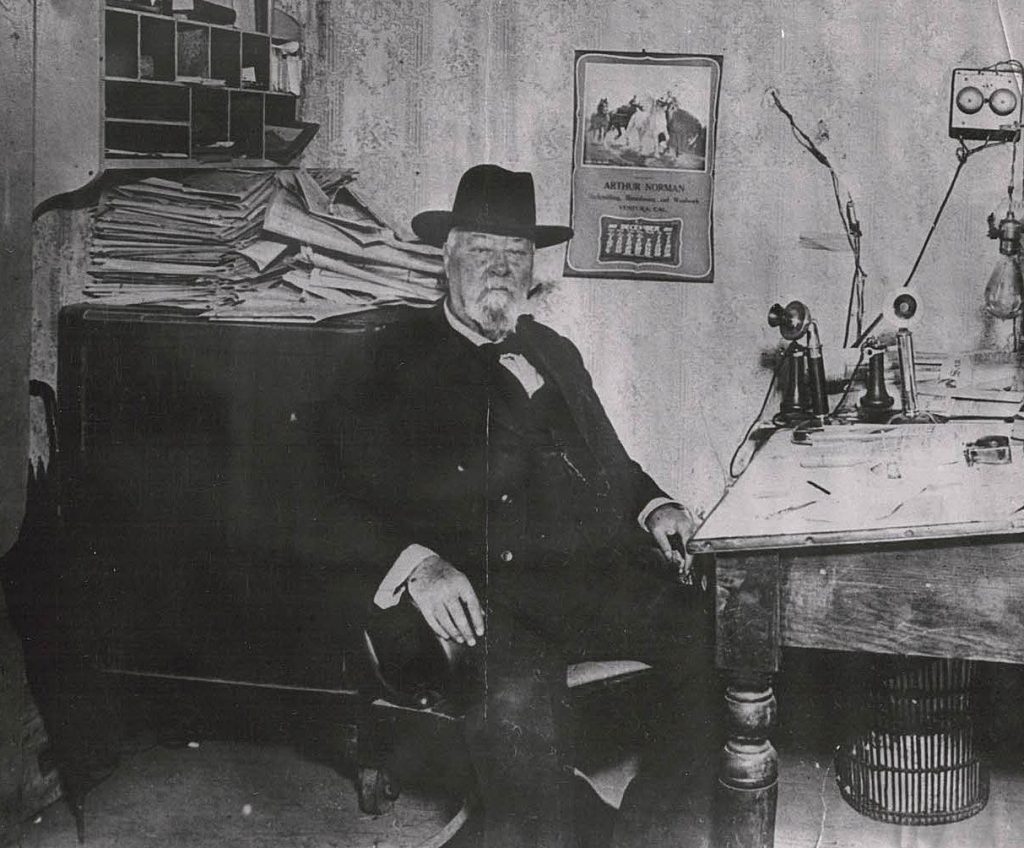

In October 1883, one of the most controversial Ventura newspaper publishers bought the Free Press. Dr. Stephen DeMoss Bowers was a Methodist preacher and self-taught archaeological collector who also pursued a career as a newspaper publisher.

While preaching in Santa Barbara in 1875, Bowers had been the first to excavate burial grounds on both San Nicolas and Santa Rosa islands, stripping sites and selling artifacts and skulls. He also collected heavily on Anacapa, San Miguel, and Santa Cruz islands. Historians and archaeologists generally regard Bowers as a pothunter who destroyed as many artifacts as he preserved and rendered the sites scientifically useless. Bowers sent artifacts to collectors all over the country. The Smithsonian Institution, which financed Bower’s work, credits 2,200 to 2,500 of its Native American relics to his excavations.

Bowers ran the paper until 1887 when he moved to Los Angeles. He returned in 1889 to take over the Free Press, consolidating it with the Vidette which Frank Smith had begun publishing the year before. Bowers later founded his own paper in 1891, the crusading Ventura Observer.

Broken Promises and an Election Scandal Lead to the Creation of the Ventura Democrat

While Bowers was still settling in at the Free Press, a political scandal led to the creation of Ventura County’s third newspaper and set the stage for a bitter, 10-year feud between editors. In 1882, a politically savvy Ventura attorney, J. Marion Brooks had his eye on a State Senate seat held by George Steele. Steele managed a huge ranch owned by an attorney for the Southern Pacific Railroad. Ed Sheridan of the Signal supported Brooks, thinking he would not be in the pocket of the powerful railroad.

Brooks narrowly lost the election and challenged the results, alleging 60 counts of voting irregularities and fraud. Brooks’ challenge was upheld and he was awarded the State Senate seat. Just three weeks after the 1883 election, Sheridan was furious when Brooks voted in favor of a bill strengthening state Railroad Commission regulations. In the Signal, Sheridan accused Brooks of being a sellout. Stung, Brooks along with other Ventura Democrats, decided Ventura County needed a Democratic newspaper of his own.

On November 17, 1883 the Ventura Democrat came out as a weekly published on Saturday. On that day the San Luis Obispo Mirror called it “A very bad idea. One first-class well-supported paper is better than two half-starved sheets.” Sheridan, writing in the Signal, said the reason Brooks “wants a paper is he cannot handle the Signal to suit his wishes.” Brooks punched back: “Ventura County, a majority of whose citizens are Democratic in politics, has no newspaper which is in harmony with the sentiments of the majority of its tax-paying population.”

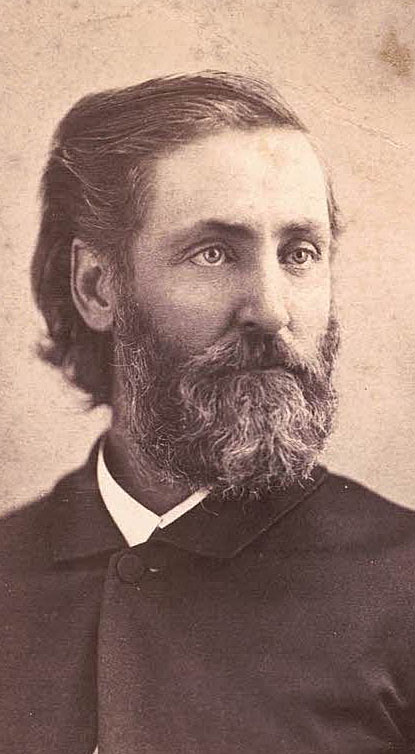

The politically ambitious Brooks had his newspaper but very little time to run it. As fate would have it, longtime newspaperman John McGonigle got off the steamer from Santa Cruz in Ventura to stretch his legs. McGonigle was traveling to Los Angeles where he was considering buying the Evening Express newspaper. While walking around Ventura, he happened to bump into Brooks and the two men hit it off. McGonigle never bought the Express. On his return trip he looked up Brooks and signed a lease for the Ventura Democrat. He bought the paper a few months later.

Stage is Set for a Feud Between Bowers and McGonigle

McGonigle was editor of the Democrat for 32 years and his feud with Bowers was legendary. McGonigle, a party-line Democrat, could not stand Bowers who he said, “swells and struts about like a pugnacious turkey gobbler, a man who would umpire a dog fight for notoriety and preside over a hen roost if he thought the chickens could appreciate his greatness.”

McGonigle took delight in supporting almost everything Bowers opposed and called Bowers “the biggest hypocrite and greediest human hog that ever walked the streets of Ventura” adding it was “just as natural for Parson Bowers to lie as it is for him to eat.” “Parson Bowers (says) we have called him a thief, liar, mountebank, disreputable, dishonest, ready to sell out to the highest bidder, etc. He seems to know himself better even than we do, for we have never called him a thief.”

An outspoken prohibitionist, Bowers did not shy away from the big political controversy of the day, alcohol use. Bowers had asked the Ventura Town Council to close saloons at 11 p.m. The hard-drinking McGonigle never passed up an opportunity to mock the Methodist minister, “Bro. Bowers of the Free Press returned from his camping trip on the Conejo Saturday night. He struck a colder climate than anticipated and shortened his stay in consequence. The nights were chilly, and he didn’t have his jug along.” Not to be outdone. Bowers wrote in 1887, “The Democrat intimates that our description of the business of this town was not sufficiently full in-so-much as we omitted the billiard tables and saloons. Well we didn’t want to appropriate the whole ground, so we left this to the Democrat where it properly belongs.”

PN3542, MVC Library & Archives collection.

The Free Press even alleged the “Democrat has so many nasty remarks to make about the Free Press it ran out of Italic F’s.” They were quick to point out the Democrat’s business shortcomings, describing the editor as “indignant because one of the town’s merchants is using a rubber stamp to print his letterhead instead of getting it done at one of the newspaper’s printing offices. The Free Press ran the opinion that the merchant was only “doing what McGonigle and the Democrats have been preaching for years – free trade.” Especially painful was when the Democrat’s presses broke down and they had to appeal to Bowers for help. “Each week we have come in for a share of its villainous abuse,” Bowers complained, “and then to have been asked to run it off our own press.”

Bowers was the only Ventura editor known to have been beaten by an angry reader. Bowers, now publishing his crusading paper the Observer, accused Undersheriff Charles “Bully” Wason of illegally accepting county tax money. The grand jury agreed with Bowers. The next morning, an angry Wason barged into Bower’s office. It’s not clear who swung first but the slightly built Bowers quickly lost to the 209-pound Wason. An amused McGonigle referred to the fight as between “John L. Wason and Jake Kilrain Bowers.” John L. Sullivan and Jake Kilrain were popular bare-knuckle fighters of the 1880s.

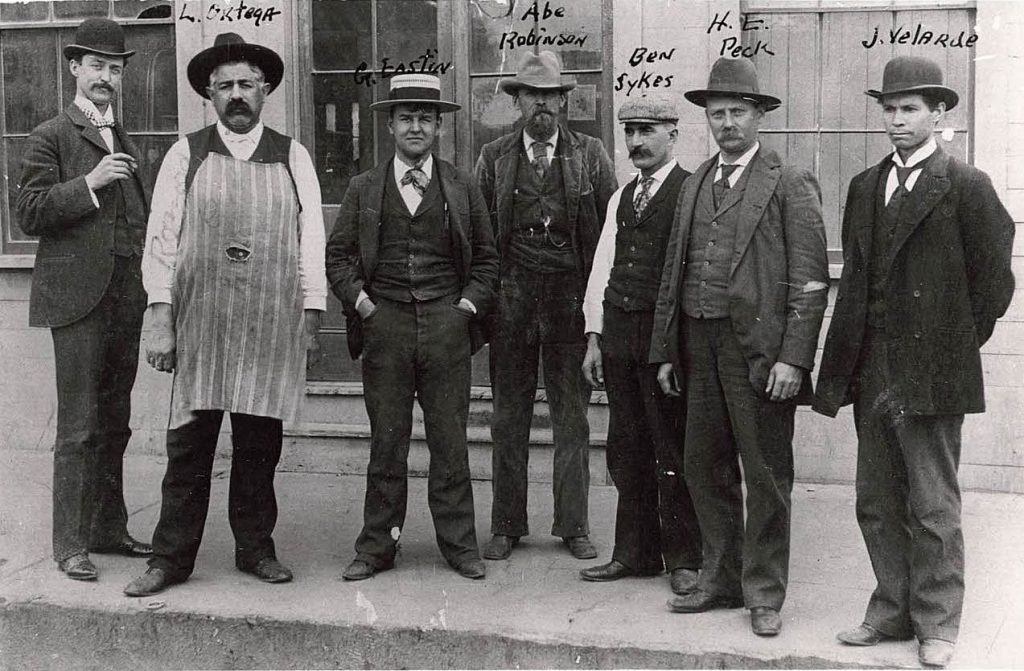

PN1093, MVC Library & Archives collection.

In 1893, Bowers sold his paper and left the county for the San Diego area and never returned. He dug fossils in the San Diego County desert and took on an assignment from the U.S. Geological Survey to survey fossils around Riverside. Bowers preached into his mid-70s delivering two sermons weekly. In the first days of 1907 he suffered a stroke and died.

McGonigle edited the Democrat, renamed the Post in 1912, until ill health forced him to retire in 1915. He died two years later and was buried in Cemetery Memorial Park. His remains were re-interred at Ivy Lawn cemetery in 1944.

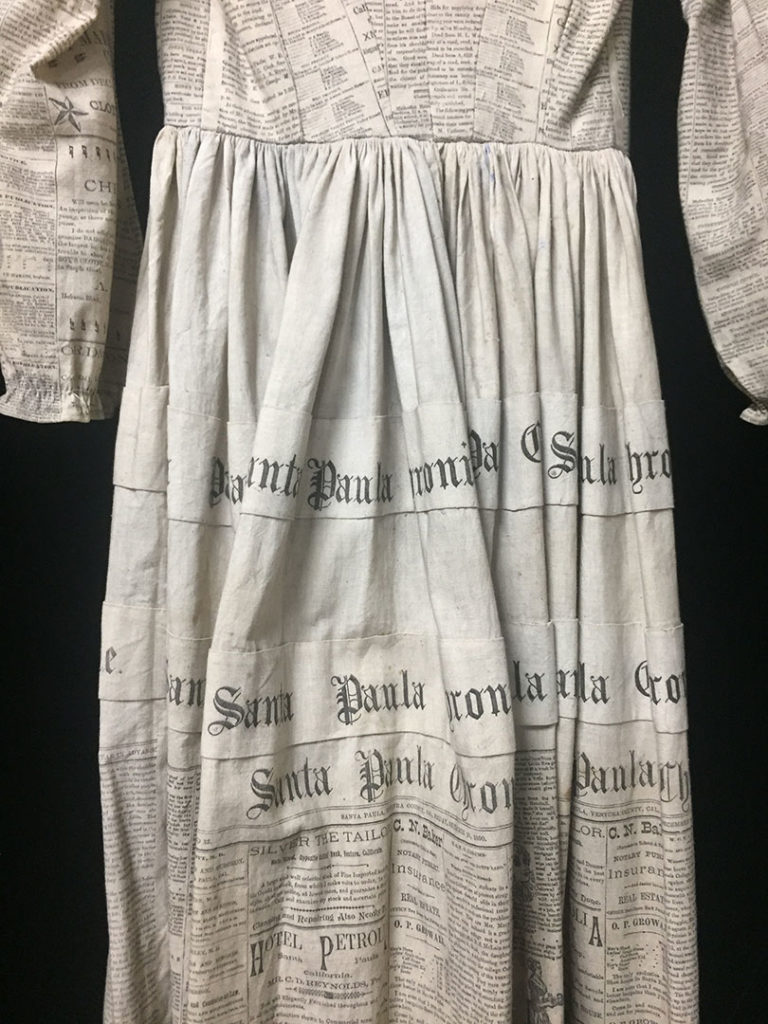

Newspaper-Inspired Dress Part of Museum’s Collection

Santa Paula was the first city in the county outside of Ventura to have its own newspaper. The Graphic was first published in 1887. While he ran the Ventura Free Press, Stephen Bowers also served as a Methodist pastor in Santa Paula and he established a paper there called the Golden State. In 1888, C. J. McDivitt started the Santa Paula Chronicle.

The gray/tan dress of coarse weave cotton pictured left is printed with articles and ads from the December 26, 1890 edition of the Chronicle. The dress is believed to have been made for Mrs. A. C. Hardison for a special occasion. It has long sleeves, a straight band collar and two bands across the skirt. The dress closes in front with five small black buttons with shanks. It was made sometime between 1900 and 1920.

Newspapers Available on Microfilm in The Research Library

The Research Library has an extensive collection of Ventura County’s early newspapers, most of it on microfilm. Even if you are not researching a specific event, it can be fun to “go back in time” and browse the pages of these publications.

Santa Paula Chronicle · 1888–1992

Santa Paula Review · 1928–1949

Santa Paula Times · 1993–2003

Moorpark Enterprise · December 30, 1915 – December 29, 1955

Oxnard Press Courier · January 7, 1899 – October 22, 1992

Santa Barbara Weekly Press · July 1869 – November 1873

Ventura Independent · April 16, 1896 – July 1903

Ventura Free Press · weekly, November 14, 1875 – December 1921

Ventura Free Press · daily, December 1, 1890 – June 27, 1891

Ventura Signal · April 22, 1871 – April 4, 1885

Ventura Vidette · June 4, 1889 – December 1890

Ventura Weekly Democrat · January 17, 1891 – December 1901

Los Angeles News · October 1, 1864 – May 15, 1868

Los Angeles Star · May 17, 1851 – December 18, 1874

Make History!

Support The Museum of Ventura County!

Membership

Join the Museum and you, your family, and guests will enjoy all the special benefits that make being a member of the Museum of Ventura County so worthwhile.

Support

Your donation will help support our online initiatives, keep exhibitions open and evolving, protect collections, and support education programs.

Bibliography – Early Ventura County’s Newspaper Wars

- “BOWERS, Stephen DeMoss.” Welcome to Islapedia – WikiName. Accessed June 11, 2019. https://www.islapedia.com/index.php?title=BOWERS,_Stephen_DeMoss.

- Gidney, Charles M., Benjamin Brooks, and Edwin M. Sheridan. “Newspapers.” In History of Santa Barbara, San Luis Obispo and Ventura Counties, California, 397-401. Chicago, IL: The Lewis Publishing Company, 1917.

- “John McGONIGLE.” Find A Grave – Millions of Cemetery Records. Accessed June 11, 2019. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/98121307/john-mcgonigle.

- “N. W. Ayer & Son’s American Newspaper Annual.” Google Books. Accessed June 11, 2019. https://books.google.com/books?id=kHwVq2PwUwEC&pg=PA483&lpg=PA483&dq=Dr.+Stephen+Bowers,+Ventura&source=bl&ots=jadFXukguD&sig=ACfU3U3LHVAr19BxE3mjgKTAwIF41nge5w&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwjNqeb_g6HiAhVoFjQIHdhmABEQ6AEwEHoECAkQAQ#v=onepage&q=Dr.%20Stephen%20Bowers%2C%20Ventura&f=false.

- “People | Biography of Rev. Dr. Stephen Bowers (Bowers Cave, Etc.).” SCVHistory.com | Santa Clarita Valley History Archives | Research Library | SCV History In Pictures. Accessed June 11, 2019. https://scvhistory.com/scvhistory/stephenbowersbio_aps.htm.

- Pollak, Alan. “President’s Message.” Santa Clarita Valley Historical Society – Gold. Oil. Filming. Disasters. Santa Clarita Valley: Birthplace of California History. Last modified June 2018. https://scvhs.org/wp/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/dispatch44-3.pdf.

- “Ventura County Genealogical Society – Hist-Storke SanBuenaventura.” Welcome to the Ventura County Genealogical Society. Accessed June 11, 2019. https://venturacogensoc.org/cpage.php?pt=73.

- “Ventura County Star Free Press.” In John P. Scripps Newspaper Group, edited by Paul K. Scripps, 9-17. San Diego, CA: John P. Scripps Newspaper Group, 1978.

- Ventura County Star-Free Press. “80-plus newspapers have covered county.” January 1, 1973.

- Ventura County Star-Free Press. “A peek at the past of the S-FP, Days of hot metal type, fervid politics.” January 20, 1980.

- Ventura County Star-Free Press. “Controversy was Stephen Bower’s companion.” February 11, 1973.

- Ventura County Star-Free Press. “Free Press Was Almost The First.” October 19, 1965.

- Ventura County Star-Free Press. “The Fourth Estate: 100 Years Later, The Story of Seven.” April 25, 1971, 10-15.

- Ventura County Star-Free Press. “Ventura’s first newspaper made everybody mad.” January 25, 1976.

- “Ventura County, California.” Google Books. Accessed June 11, 2019. https://books.google.com/books?id=7gAZAAAAYAAJ&pg=PT5&lpg=PT5&dq=Dr.+Stephen+Bowers,+Ventura&source=bl&ots=DQ3caMGvqN&sig=ACfU3U2gkeQBnBqmGUjxY1928RZHgXaJIA&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwjNqeb_g6HiAhVoFjQIHdhmABEQ6AEwD3oECAgQAQ#v=onepage&q=Dr.%20Stephen%20Bowers%2C%20Ventura&f=false.

- “Ventura Observer 14 August 1891 — California Digital Newspaper Collection.” California Digital Newspaper Collection. Accessed June 11, 2019. https://cdnc.ucr.edu/?a=d&d=VO18910814&e=——-en–20–1–txt-txIN——–1.