by Library Volunteer Andy Ludlum

One hundred years ago a tragic mix of poor judgment, navigational errors, irregular currents, and fog cost 23 sailors their lives. Shipwrecks, 100 miles north of Ventura on a notoriously treacherous point on the central coast, captivated county residents for over a month as many planned family outings to view the largest peacetime loss of U.S. Navy ships.

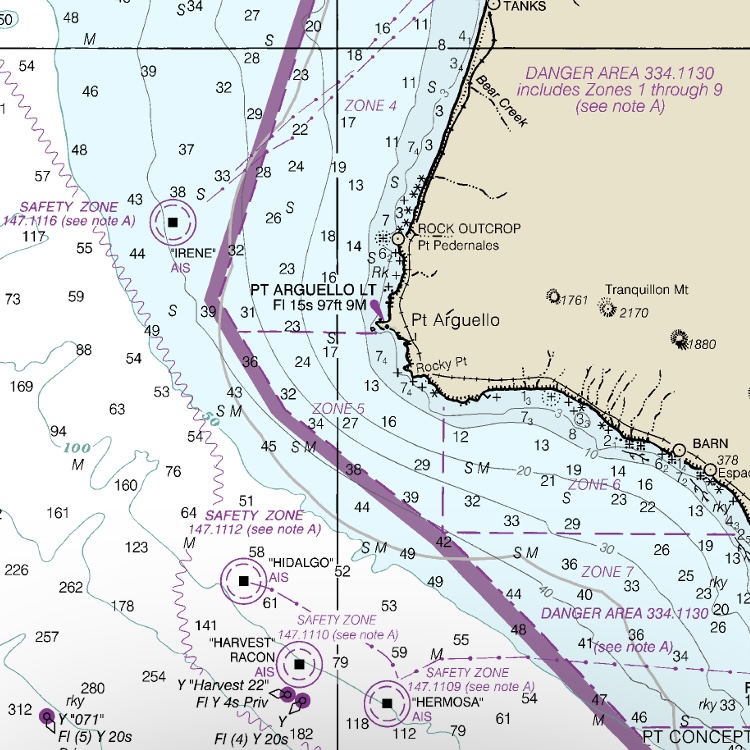

On Saturday, September 8, 1923, in less than five minutes, seven naval destroyers ran aground on the jagged rocks and reefs of Honda Point, just off the present-day Vandenberg Space Force Base. Located near the entrance to the Santa Barbara Channel, Honda Point, also known as Point Pedernales, had been feared by mariners since the 16th century when Spanish explorers first called the area the “Mandibula del Diablo” or “Devil’s Jaw.”

The Race to San Diego

That morning, the 14 ships of Destroyer Squadron 11 set out at 8:30 to participate in a war games exercise. They had 24 hours to conduct tactical and gunnery exercises enroute to San Diego. A Naval Academy graduate and 28-year officer, Captain Edward H. Watson was the commodore of the squadron aboard the USS Delphy. To meet the tight deadline, the ships stayed in close formation and cruised at a brisk 20 knots, about 23 miles per hour.

The Delphy set the navigational course as the flagship. The ships met unusually rough conditions. Seven days earlier a 7.9 magnitude earthquake struck the main Japanese island of Honshū and the quake created large swells and powerful currents that reached as far as the California coast.

A five-year-old warship, the Delphy had the latest radio direction-finding equipment, which picked up signals from a station at nearby Point Arguello. The state-of-the-art technology was new and not always trusted. Traditionally, navigation was based on “dead reckoning” which estimated a ship’s position based on its speed and heading. With the unusual swells and currents, the calculations were wrong, and the fleet was several miles off course. Coupled with darkness and heavy fog, Captain Watson did not know they were positioned near the mouth of the “Devil’s Jaw” instead of the safe, open waters of the channel.

Disaster on the Rocks

Not wanting to slow down and miss his deadline, and not believing the radio signals from Point Arguello, at 9:00 P.M. Captain Watson ordered his ships to turn east into what he thought was the channel. Instead, the Delphy headed straight into a thick fog bank hiding the deadly rocks of Honda Point.

Five minutes later, the Delphy hit the jagged rocks at full speed. It tore open her hull and the ship quickly capsized to the right. Three sailors died as men were trapped and fires broke out in the engine room. On the deck, sailors were thrown off the ship. The Oxnard Press-Courier carried a wire service report that quoted machinist mate W. G. Gerlach who said a sailor was “hooked out of the water” and pulled aboard the Delphy. Blinded by the oil in the water and “crazed by the horrors of the accident,” the terrified sailor could not hold on to a rescue rope. He had to be lashed to the deck house of the Delphy and left alone until he could be rescued in the morning. Gerlach said the “frantic calls of the crazed victim pierced the night.”

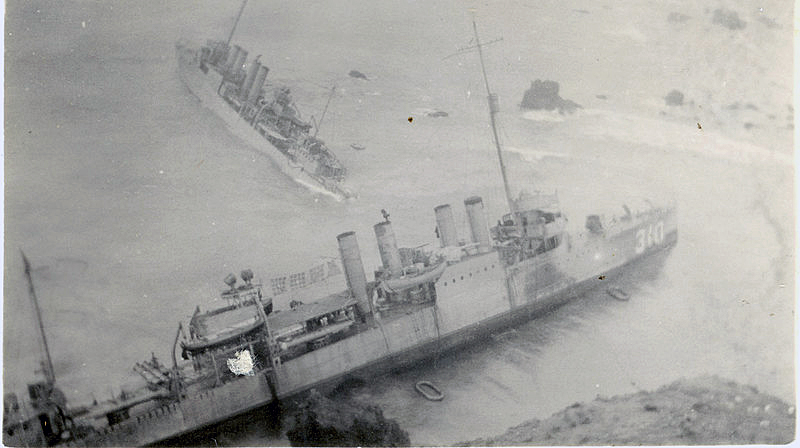

Crew members raced to sound the Delphy’s siren to alert the ships following her lead. It was too late. The USS S. P. Lee, only a few football fields behind, turned left to avoid hitting the ship but ran aground in shallow water. The impact destroyed the propellers and within minutes the ship was pushed ashore, broadside to surf. The ship’s hull was ripped open, and she was abandoned.

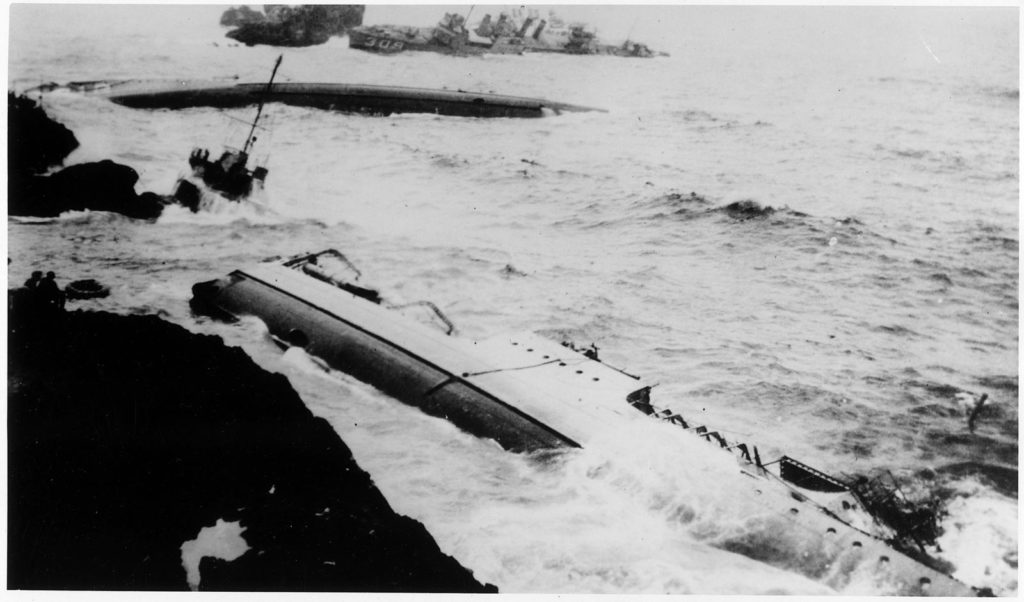

Despite the warning sirens from the flagship, the USS Young had little chance to slow or turn before she hit the rocks at 20 knots. Her hull was torn open from stem to stern, and she keeled over and sank. Dozens of crew members on the deck were thrown into the water. Coated in fuel oil, some men swam for shore while others struggled back onto the side of the capsized destroyer. There they clung to the ship’s slippery port side, holding on to openings created by smashed porthole windows. But the sailors below deck, in their bunks or the engine and boiler rooms, were trapped. Twenty of the Young’s crew died. Survivors made it off the stricken ship using a rope line strung between the Young and the closest crippled ship, just 25 yards away. Some of the men were so soaked in oil they slipped off the rescue ropes, falling into the water.

Three other ships ran onto the rocks. Sighting the breakers ahead, the captain of the USS Woodbury turned, but broadsided a rocky island and her hull was torn open. As she sank against the island, her engine rooms flooded. The Press-Courier reported men in the engine room worked until water was up to their shoulders in a futile attempt to keep the ship’s lights on. “When the lights went out…the darkness added more terror to the frantic men.” The relentless pounding of the surf began to tear the ship apart. The crew abandoned ship and climbed down to the newly named “Woodbury Island,” where they were rescued the next morning.

The USS Nicholas hit bottom before she could turn and damaged her rudder and propeller. Out of control, she hit bottom several more times before wedging into rocks which punched several large holes in her hull. The ship was flooded with breakers washing over her deck when the crew abandoned her at first light.

The USS Fuller was also unable to stop, but a last second turn saved the ship from hitting the jagged rocks head on. One side of her hull was shredded by the impact, and it was clear the ship would sink once the heavy surf pulled her off the rocks. The crew abandoned ship safely onto the rocks.

The USS Chauncey, which had avoided the rocks, ran up on the shore with enough force to ride several feet out of the water. With the ship stuck fast and relatively safe, the crew went to rescue sailors in the water beside the capsized Young. Eventually the pounding surf began to break the Chauncey apart and it too was abandoned.

Two ships, the USS Farragut and the USS Summers were alerted by warning sirens in time to reverse their engines, slow down and run aground gently. They backed into the safety of deeper waters.

Five ships avoided the rocks. Commander Walter G. Roper, in charge of destroyers running at the rear of the column, intercepted the radio bearings that were ignored by the Delphy and correctly determined the fleet’s position. When the ships reached the turning point, Roper ordered them to slow down and stop.

Heroic Efforts to Rescue Bruised and Battered Sailors

Rescue efforts began immediately. The destroyers that avoided the rocks sent out lifeboats. Local ranchers rigged up “breeches buoys” from the tops of the cliffs and lowered them down to the ships below. A breeches buoy is a rescue device resembling a life preserver with leg harness attached to a rope that works like a zip line. The entire crew of the S.P. Lee was brought ashore by a breeches buoy. Chief Boatswain’s Mate Arthur Peterson swam from the Young to the Chauncey to set up a lifeline for his shipmates to ferry themselves across to the Chauncey. Ultimately, 11 trips were made allowing nearly 70 sailors to escape the Young. Peterson was cited for his bravery. Fishing boats plucked crew members off the grounded ships. Some sailors made it to the shore and waded through the rocks. The last sailor was not rescued until Sunday afternoon.

Ventura County residents first read about the disaster in Monday’s newspapers. The Press-Courier reported that “[in] pitch blackness, 14 shivering, oil smeared refugees of the U.S.S Delphy and Young, some naked and others clad only in light night shirts, were loaded aboard a Southern Pacific train early Sunday morning and taken to Cottage Hospital in Santa Barbara.” While none of the 14 sailors would die of their injuries, many were semi-conscious and in shock. They were “blinded by oil, which poured from the great tanks of the reefed vessels and covered the surface of the water, stunned by the shock of the catastrophe, bruised and bleeding from being thrown by the breakers against the sharp rocks and chilled by the night air after struggling in the cold water.” The Ventura Morning Free Press reported that one of the injured sailors from the Delphy was J.M. Mays, a former Ventura resident. He was fortunate to survive as he was in his bunk at the time of the crash. Mays was among the first Venturans to enlist during World War I.

On Sunday afternoon a special train took hundreds of weary and shocked sailors back to their home port of San Diego. Most were badly gouged after crawling across the sharp rocks. Over the next two days, 800 sailors were treated, fed, clothed, and sent home.

Eighteen men stayed behind, assigned to protect the stranded destroyers from looters as well as to watch for the bodies of the dead and recover them if possible. By Monday, only a few bodies had been recovered. The heavy surf frustrated rescuers trying to reach the sailors imprisoned in the hull of the Young. On Wednesday, wrecking crews cut large holes in the port side of the Young to locate the bodies of the missing crew members believed trapped in their compartments. Not a single body was found, which led authorities to speculate the missing men had drowned in attempts to swim to shore in the heavy breakers.

Within days there were reports that currents had carried bodies to Ventura County. County Sheriff Robert Clark, along with a traffic officer and a Free Press reporter, spent several hours searching the causeway on the Rincon after receiving a report that three bodies had washed ashore. Clark searched for two days before deciding the report was false.

By midweek, Navy warships patrolled back and forth in dense fog in the channel off the Ventura coast. Three missing men were sighted on a raft near Wilson Rock, three miles from San Miguel Island. It was feared the life raft might be “tossing about helplessly on the sea” with the men suffering from exposure and thirst. The search was called off by the end of the week when no raft was found.

On Friday, a board of investigating officers left San Diego for Honda Point. Their decision fixing the blame for the accident was forwarded under seal to Washington. The Navy also announced a final death toll, 23 sailors. Seventeen bodies were recovered. The other six were never found and were believed to have been swept out to sea.

Sailors Fire Upon Looters

The sailors guarding the site were quickly challenged by looters. The armed guards opened fire across the bows of two small boats attempting to tie up on either side of the wreck of the Nicholas, after they ignored repeated warnings to back off. Two of the pirates were reportedly hit and another leaped into the water to escape. While permitted to fire warning shots, the sailors were ordered not to shoot to kill “unless it is absolutely necessary to protect themselves or the ships.”

Six days after the accident, a Navy captain arrived on scene to take charge of the salvage operation. The recovery of small boats, lines, and deck gear was already underway. The Navy did not attempt to salvage the seven destroyers. They were damaged beyond recovery and declared a total loss. According to the Ventura Weekly Post and Democrat the total value of the lost destroyers was $10,500,000, more than $187 million today. The Navy concentrated on retrieving weapons, equipment, and records before the ships were pulverized by the relentless surf. The material saved included many of the ships’ torpedo tubes, radios, documents, and whatever else was worth the effort. Men used a tractor to pull seven torpedoes from the water. It was too dangerous to attempt to recover the ships’ guns and other heavy items, particularly on the wrecks furthest from shore.

Wreck Site Becomes Exotic Day Trip for Curious Venturans

Curious Venturans immediately began plotting ways to see the accident scene. It was a rough 100-mile car trip to Honda Point. Several drivers set out Monday only to become marooned in the sand and forced to turn back. Others reached the wreck site by driving to Lompoc where they took a rough, sandy road to the coastal town of Surf. From there, they could walk seven miles to the wreck site. Motorists were cautioned not to attempt the challenging route unless they had “full confidence” in their car.

The hiking became unnecessary when Southern Pacific began stopping two of its trains at a point that was just a five-minute walk from the wreck site. The railroad was reluctant to put on special trains. They feared that would be perceived as using the “greatest disaster that has ever befallen the United States Navy” as a money-making scheme.

But the railroad was not immune to pressure from curiosity seekers. By the Wednesday after the disaster, Venturans could leave town on a 10:30 a.m. northbound train and arrive at Honda Point at 1:19 p.m. They would spend over three hours at the site, before leaving Honda at 4:30 p.m. for Santa Barbara where they would pick up another train for Ventura. With the train eliminating the most dangerous parts of the trip, hundreds of Ventura County residents were expected to travel to view the wrecks on Sunday. On Friday, The Weekly Post and Democrat offered tips from the local automobile club on best car and train routes to the site. The round-trip train ride cost $7, about $125 today.

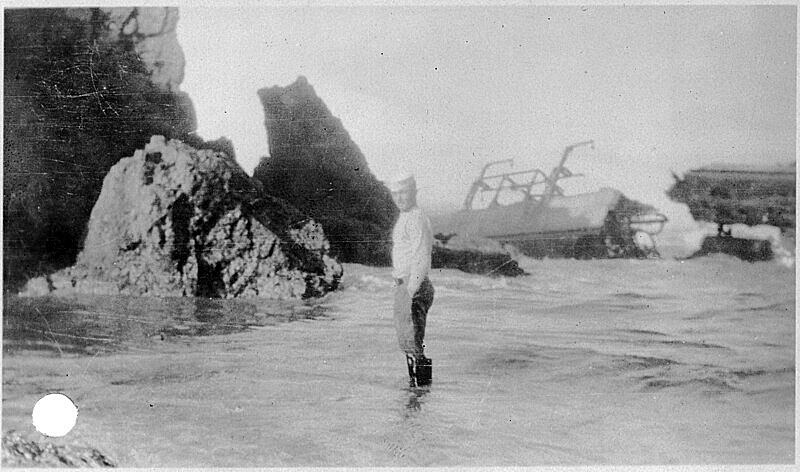

The Free Press reported “thousands of people went to Honda Sunday by auto and train.” In Ventura, Southern Pacific sold 24 round trip tickets. Hundreds of cars drove to Lompoc and Surf where they could meet the train. The newspaper said, “They were not disappointed at the awe-inspiring sight of Uncle Sam’s great ships piled up on the rocks, some upright, others in pieces and still others breaking up.” More than 20 couples and their children came from Oxnard. They told the Press-Courier that they saw the recovery of four bodies. An angler “worked feverishly in the water putting one body into a wire basket so it could be hoisted to safety.” It was wrapped in canvas and taken to the train station where piles of caskets awaited. A sailor told them the story of two brothers on different destroyers. The older brother drowned, and the younger brother reached shore safely. For days, he searched continuously for his brother’s body until it washed ashore on Sunday. That afternoon, the Nicholas broke apart under the pressure of the huge waves.

Over the next month, the county’s newspapers, which normally celebrated the visits of out-of-town family and friends, regularly featured the names of residents bound for Honda Point. The Free Press described how a Ventura couple, their children and a friend saw the “wonderful sight as waves broke over the jagged rocks.” Expeditions to see the shipwrecks were noted in the Weekly Post and Democrat’s regular column entitled “Clubs, Fraternal, Social, Women’s Interests.” Thirty-six members of an Oxnard Oddfellows Lodge combined an initiation ceremony with a visit to the wreck site.

Teenage sweethearts from Ventura were emboldened after their visit to the wreck site. They went directly to San Luis Obispo and got married. They told the license clerk they were 21 and 18. Later they admitted they had “acted hastily,” no doubt in part due to the angry reaction of the bride’s mother. She later told a judge that her daughter was only 17, too young to be married without parental consent. The couple did not contest the mother’s suit to have their marriage annulled.

The pounding surf put an end to the sightseeing expeditions. Six weeks after the accident, the bodies of three sailors were recovered, the last to be found.

Court of Inquiry Fixes Blame on Captain

For 19 days beginning September 17th, a Court of Inquiry sifted through testimony and evidence. In his testimony, Captain Watson took the blame for the shipwrecks but said his decisions were backed up by 30 years of naval experience. He said he found the radio navigation report from Point Arguello confusing. He claimed, “Because of the extraordinary demands upon the station for service due to the proximity of many other ships in the vicinity…we were unable to get our bearing promptly. When messages came telling us we were north of Arguello, I could not believe it. We had traveled 120 miles from the time we had received our bearings earlier in the day. I did not believe it was possible we were still north of Arguello.” The court ruled that the disaster was the fault of the fleet commander, Watson, and the flagship’s navigators. It also cited 23 officers and men for their outstanding performance saving lives, including Commander Roper who stopped the ships under his command before they turned into danger.

Largest Group of Officers to be Court-Martialed in Navy History

The panel recommended 11 officers be bound over for a general court-martial on charges of negligence and “culpable inefficiency to perform one’s duty.” It was the single largest group of officers ever court-martialed in Navy history. After weeks of hearings and testimony, the court found three officers guilty: Captain Watson, Squadron navigator Lieutenant Commander Donald Hunter, and the skipper of the Nicholas, Lieutenant Commander H. O. Roesch. The other eight officers were quickly acquitted. In one case, the panel deliberated for only 15 minutes. Upon review, Rear Admiral S. S. Robison later set Roesch’s conviction aside, but Watson and Hunter lost their chance for future promotion. Watson was stripped of his seniority and was assigned to the naval district at Honolulu. He served as Assistant Commandant of the Fourteenth Naval District in Hawaii until he left active duty in November 1929. Hunter was assigned to the U.S. S.S. Nevada as navigating officer and retired in 1929.

Speculation About Contributing Factors Fascinate the Public

While the official inquiry clearly determined that the accident was caused by errors in judgement made by the commanders and navigators, there remained a public fascination with the many “contributing factors” to the tragedy. The squadron navigator, Lieutenant Commander Hunter, testified at his court martial, “I think there is also a possibility that abnormal currents caused by the Japanese earthquake might have been another contributory cause, or magnetic disturbances connected with the solar eclipse affected the compass – but of these I cannot, of course, speak with any first-hand knowledge.”

The Press-Courier quoted an experienced channel captain who claimed that when he traveled past Honda Point on that Saturday afternoon, his compass readings were wrong and indicated he was ten miles off his actual position. The captain said that he was positive “some sort of electrical disturbance” had affected compass readings and might account for the wreck of the destroyers.

The Simi Valley Star reported that another experienced coastal captain suspected that the destroyers might have been pulled to their fate by an unusual current, what he called an “underground river.” He claimed to have experimented with the current at Honda Point years earlier. Using pieces of driftwood sunk at various levels, he found the deeper pieces went ashore more rapidly than those on the surface. He believed an undersea ocean river “flows far out at sea, towards the Honda beach, passes under Arguello and out under the surface of the Santa Barbara channel.”

It was the Star that reported a most unusual coincidence, a note found at an Ojai dry goods store that foretold the sea tragedy weeks before it happened. The chairman of the Santa Barbara Board of Supervisors, Howe S. Deaderick, was employed by the Hickey Brother’s dry goods stores. Deaderick claimed that three weeks before the accident, a clerk at the Ojai Hickey Brothers store found a roughly drawn marine map in the center of a shipment. The map of the Pacific had a line that started in San Francisco and was drawn about two-thirds of the way to Los Angeles. It stopped at approximately Honda Point. In the margin were the words, “three weeks from Saturday, lots of ships, plenty trouble.” Deaderick did not tell anyone about the note until after the accident.

The Sea Carries Away the Seven Warships

On October 4th, the Fuller disappeared beneath the waves, leaving only four of the seven destroyers visible on the rocks. The next week, life preservers and other material from the destroyers, carried over a hundred miles by the strong currents, washed up on the beach near the second Rincon causeway. An experienced channel mariner told the Press-Courier that the heaviest swell in 40 years was pounding the battleships to pieces. Within a month, only three of the destroyers were still visible. The S.P. Lee, the Chauncey and the Woodbury were above water, but listing badly and were expected to be demolished by the first severe storm. By the end of 1924, all the ships had been reduced to scattered pieces. After they stripped the wrecks of items of value, the Navy put them up for salvage. In December a Santa Monica salvage firm was the only bidder for the seven destroyers. They offered $1,650, less than $30,000 today.

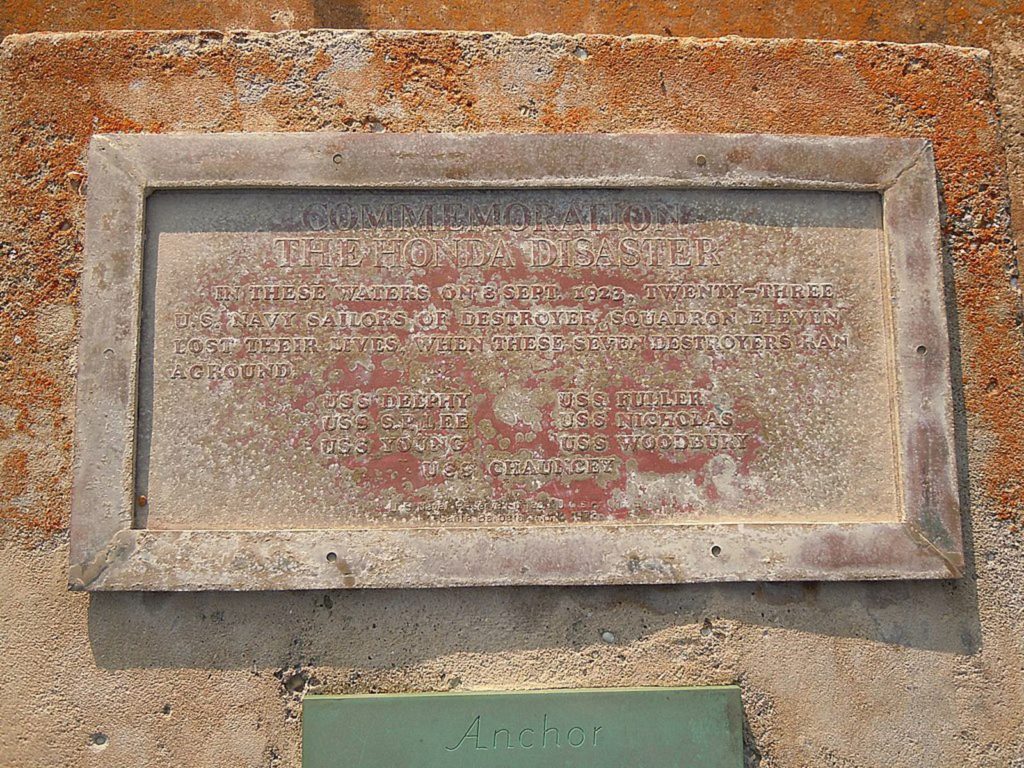

It was the sea that carried away most of the ships. Some pieces remain today. Vandenburg Space Force Base owns the site and access is by permission only. The wrecks are some of the least dived in California. The site is protected by law and artifacts cannot be removed. There is a plaque at the site of the crash honoring those who lost their lives. An additional plaque, with a propeller from the Delphy, and a bell from the Chauncey stands in front of the Veteran’s Memorial Building in Lompoc.

The area around Honda Point is not easily accessible and is best viewed from the Amtrak train. One hundred years later, mariners are still relieved when they safely pass the “Devil’s Jaw.” Perhaps they hear the words of channel captain R. P. McChesney in 1923. “Whenever I pass that spot, I stand on deck and take off my hat, not only in respect to the greatness of forces that exist there, but also in gratitude that once more I am safely by the most dangerous place on the entire California coast.”

Make History!

Support The Museum of Ventura County!

Membership

Join the Museum and you, your family, and guests will enjoy all the special benefits that make being a member of the Museum of Ventura County so worthwhile.

Support

Your donation will help support our online initiatives, keep exhibitions open and evolving, protect collections, and support education programs.

Bibliography

- “Disaster at Honda Point.” U.S. Naval Institute. Last modified September 29, 2020. https://www.usni.org/magazines/naval-history-magazine/2020/october/disaster-honda-point.

- “Events of the 1920s–Honda Point Disaster, 8 September 1923 — Later Views of the Wrecks.” The Public’s Library and Digital Archive. Accessed August 9, 2023. https://www.ibiblio.org/hyperwar/OnlineLibrary/photos/events/ev-1920s/ev-1923/honda-8.htm.

- “Honda Point Disaster.” Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia. Last modified May 24, 2023. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Honda_Point_disaster.

- Morning Free Press (Ventura). “Attack Raiders of Wrecked Destroyers.” September 14, 1923, 1.

- Morning Free Press (Ventura). “Bodies of Three Victims Found.” October 18, 1923, 1.

- Morning Free Press (Ventura). “Captain Takes Blame for Big Ship Wrecks.” September 19, 1923, 1.

- Morning Free Press (Ventura). “Commander Pye Exonerated in Honda Probe.” November 28, 1923, 4.

- Morning Free Press (Ventura). “Free Ship Commander.” November 21, 1923, 3.

- Morning Free Press (Ventura). “Indict Commander in Honda Wreck.” November 26, 1923, 6.

- Morning Free Press (Ventura). “Last of the Fuller.” October 5, 1923, 2.

- Morning Free Press (Ventura). “Locals.” September 24, 1923, 4.

- Morning Free Press (Ventura). “Many Venturans Will Visit the Scene of the Wreck Sunday.” September 15, 1923, 1.

- Morning Free Press (Ventura). “Mound News.” September 19, 1923, 3.

- Morning Free Press (Ventura). “Name Commander to Succeed Watson.” December 17, 1923, 12.

- Morning Free Press (Ventura). “Only Three of Destroyers Are Still Afloat.” November 7, 1923, 1.

- Morning Free Press (Ventura). “Recover Body.” September 13, 1923, 1.

- Morning Free Press (Ventura). “S. P. to Stop Trains to View Big Ship Wreck.” September 12, 1923, 1.

- Morning Free Press (Ventura). “Santa Monica Bids for Honda Wrecks.” December 24, 1923, 5.

- Morning Free Press (Ventura). “Search Shores Near Here for Missing Bodies.” September 13, 1923, 1.

- Morning Free Press (Ventura). “Start Trial of Another Officer in Navy Crash.” November 26, 1923, 1.

- Morning Free Press (Ventura). “Town Topics.” September 17, 1923, 4.

- Morning Free Press (Ventura). “Venturans See Wreck Breakup.” September 17, 1923.

- “A Naval Tragedy’s Chain of Errors.” U.S. Naval Institute. Last modified April 5, 2023. https://www.usni.org/magazines/naval-history-magazine/2010/february/naval-tragedys-chain-errors.

- Oxnard Press-Courier. “11 Officers to Face Naval Court Martial.” October 24, 1923, 1.

- Oxnard Press-Courier. “Bodies of Six Wreck Victims Washed Ashore.” September 14, 1923, 1.

- Oxnard Press-Courier. “Commander W. Calhoun of Young Not Guilty.” November 20, 1923, 1.

- Oxnard Press-Courier. “Compass Acted Queerly in Destroyers Wreck.” September 15, 1923, 1.

- Oxnard Press-Courier. “Expect Government Will Rest Case Tomorrow.” November 6, 1923, 1.

- Oxnard Press-Courier. “Heaviest Ground Swell in Years Destroying Wrecked Naval Ships.” October 15, 1923, 3.

- Oxnard Press-Courier. “Men Believed Imprisoned in One of Ships.” September 11, 1923, 1.

- Oxnard Press-Courier. “Naval Court Martial Gets Under Way.” November 5, 1923, 1.

- Oxnard Press-Courier. “Odd Fellows Visit Lompoc and Vicinity.” October 8, 1923, 1.

- Oxnard Press-Courier. “Oxnard and Vicinity.” October 1, 1923, 1.

- Oxnard Press-Courier. “Oxnard and Vicinity.” October 2, 1923, 2.

- Oxnard Press-Courier. “Oxnarders Hear Weird Tales from Sailors of Pt. Honda Wreck.” September 17, 1923, 1.

- Oxnard Press-Courier. “Survivors on Special Train Headed South.” September 10, 1923, 1.

- Oxnard Press-Courier. “Wrangle Develops When Captain Take Stand.” November 7, 1923, 3.

- Russell, Shahan. “Honda Point Disaster: Where 7 Destroyers and 23 Sailors Were Lost in the Largest Peacetime Loss of U.S. Navy Ships.” Warhistoryonline. Last modified October 14, 2017. https://www.warhistoryonline.com/history/honda-point-disaster.html.

- Simi Valley Star. “Foretold Honda Sea Tragedy.” September 20, 1923, 1.

- Simi Valley Star. “Says Underground River Caused Destroyer Wreck.” October 18, 1923, 1.

- The Ventura Weekly Post and Democrat. “City Briefs.” September 21, 1923, 8.

- The Ventura Weekly Post and Democrat. “Clubs, Fraternal, Social, Women’s Interests.” October 5, 1923, 8.

- The Ventura Weekly Post and Democrat. “Former Ventura Boy Is Among Wreck Victims.” September 14, 1923, 2.

- The Ventura Weekly Post and Democrat. “From Tuesday’s Daily.” September 21, 1923, 6.

- The Ventura Weekly Post and Democrat. “Here’s How to Get to Point Arguello.” September 14, 1923, 4.

- The Ventura Weekly Post and Democrat. “Marriage to be Annulled by Court.” October 5, 1923, 3.

- The Ventura Weekly Post and Democrat. “Materials From Wrecks on Beach.” October 12, 1923, 3.

- The Ventura Weekly Post and Democrat. “Search Channel for Trace of Raft with Destroyer Men.” September 14, 1923, 1.

- The Ventura Weekly Post and Democrat. “Three Couples Seek Divorces.” November 16, 1923, 7.

- The Ventura Weekly Post and Democrat. “Clubs, Fraternal, Social, Women’s Interests.” September 21, 1923, 7.

- “Wrecks of Honda Point and the “Devils Jaw”.” Channel Islands Dive Adventures. Last modified December 30, 2020. https://channelislandsdiveadventures.com/california-channel-islands-diving/honda-point-wrecks/.