By John E. Baur

Next up on Journal Flashback, William Vandever! Vandever was Ventura’s first congressman. A Union veteran of the Civil War, his political career spanned an interesting time in American politics and history. His work highlights the numerous divisions and causes that characterized California following statehood. In this article from Volume 20, Issue 1 (1974), we can see many debates that have continued to the present day. Enjoy!

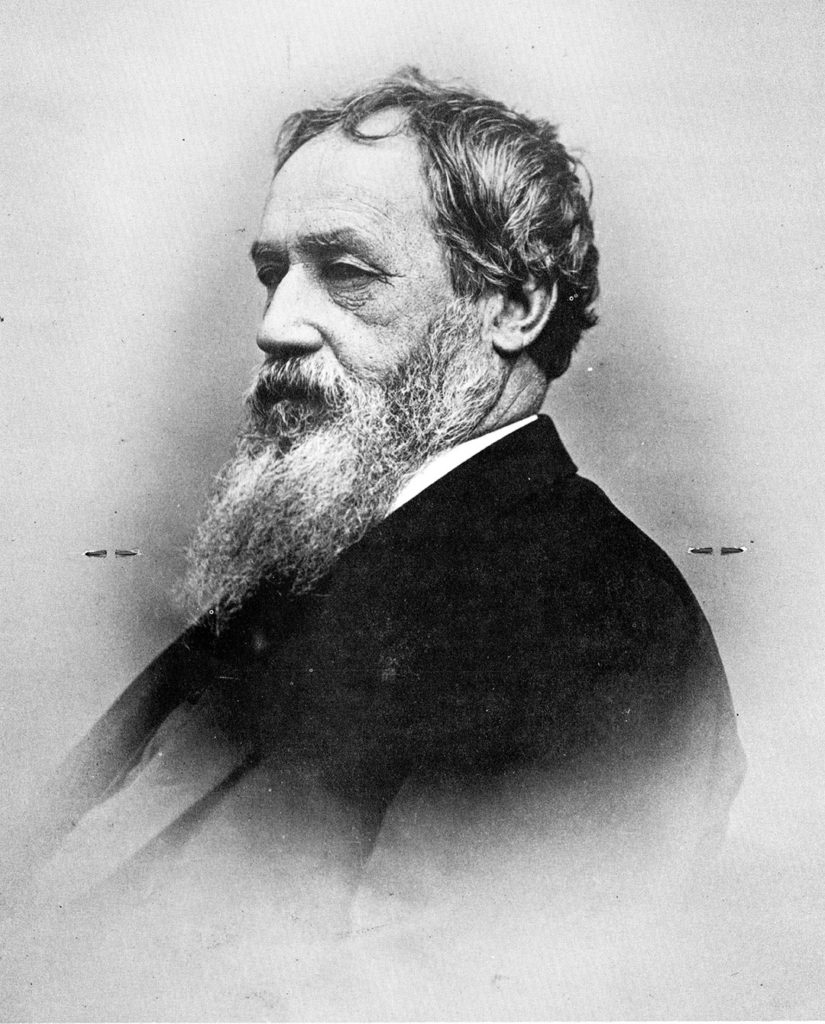

The first congressman to reside in Ventura was a man of both national achievement and local dedication. A hero of the War Between the States, he moved to California which had lured several other veterans of general rank who were attracted by the state’s unusual spirit, geography and promise. For William Vandever the way to Ventura was long and roundabout.

A reader brought to our attention that the phrase “War Between the States” was sometimes used as a pro-Confederate euphemism, although not always. We would like to flag this for readers and inform them that this is a possible connotation. After looking into Prof. Baur’s research and history, we do not feel comfortable assuming that he used it as a dog whistle indicating a pro-segregationist stance. We do not currently have enough information to be sure of Prof. Baur’s stance. We do welcome feedback from readers who can educate us on the history of the term, and we encourage readers to read up on the history of the term.

Born in Baltimore, Maryland on March 31, 1817, Vandever was educated in Philadelphia before moving in 1839 to Illinois. There William spent his early years as a surveyor of the public lands of Illinois and neighboring Iowa and Wisconsin1. In 1846 he became Editor of the Rock Island Advertiser, an influential Whig newspaper. Long interested in Whig politics, Vandever had cast his first presidential vote for William Henry Harrison in 1840. With the Whig victory of 1848, Zachary Taylor became President and young Vandever was appointed to a clerkship in Washington, D.C. Shortly afterward he became a clerk in the office of the Supervisor-General of Iowa, and in 1851 moved with his bride to Dubuque.2

Admitted to the Iowa bar the next year, Vandever began practicing law; and with the rise of the new Republican Party, which he early joined he was elected to the 36th and 37th Congresses, representing his eastern Iowa district from March 1859 until September 18613. On the tragic day of the Union defeat on the battlefield of Bull Run, the Iowa congressman offered a motion that Congress passed stating that nothing would discourage the government from preserving the Union. Practicing what he eloquently preached, he asked Lincoln’s Secretary of War, Simon Cameron, to let him raise a volunteer regiment. This was the Ninth Regiment of Iowa Volunteer Infantry with Vandever as its colonel.4

During the war Vandever was promoted to brigadier general for his valor at Pea Ridge, and later breveted a major general. He served in the Vicksburg campaign, and in 1864 saw action with Sherman in the Atlanta march. He was also present when Confederate General Joseph E. Johnston surrendered in April 1865. Despite perilous duties Vandever passed through the great conflict uninjured. For the rest of his long life, he was very active in the Grand Army of the Republic as a commander of that Union veterans’ organization in the Middle West and later in southern California.5

His old commander, President Ulysses S. Grant, appointed General Vandever a United States “Indian inspector.” During his service, 1873-77, he made several visits to California to inspect Indian conditions and was so impressed by the state’s resources and people that he eventually moved to Ventura in 1884. He was also powerfully, but negatively, impressed by the corruption in Indian Bureau politics, and told a fellow Midwesterner, D. L. Phillips, about attempts of realty sharpers to sell land in California to the government for Indian affairs purposes and gain $500,000.6

After moving to San Buenaventura, Vandever was prevailed upon by prominent southern California Republicans to run for Congress in 1886. The incumbent, a Republican and southern California’s first Congressman, Henry H. Markham, who had moved west partly to regain his health from war¬ time illness, had become sick again and declined to run for reelection in the far-flung sixth Congressional District which included fifteen counties. By 1890 however, Markham had recovered and was elected governor of California.7

Meanwhile, endowed with a fine voice and the imposing dignity of a tall, soldierly bearing, Vandever spoke widely on his first California campaign. He toured such distant towns as Los Angeles, Bakersfield, Tulare, Visalia, Hanford, Kingston, Fresno, Hollister, San Juan Bautista, Monterey and Salinas. He showed particular interest in the tariff and the economic development of the region. His Democrat opponents were severely critical of the Civil War veteran, accusing him of waving the much-exploited “Bloody Shirt.” As did many other G.A.R.-favored Republican candidates in postwar days, he emphasized the “dangers” of electing candidates who might over sympathize with former rebels. Democrats replied that Vandever lived in the past and was still fighting the tragic war.8 His opposite number, the Democratic candidate, Joseph D. Lynch, belittled the 69-year-old Vandever, calling him a “venerable old gentleman.”9 Yet Vandever also could become aggressive. At Santa Paula he charged that Democratic platforms never sympathized with home industry and that no Union general was a Democrat. The latter allegation was easily disproved by checking the voting habits of Generals Winfield S. Hancock, George B. McClellan, Henry W. Slocum, Joseph Hooker, George G. Meade and George A. Custer.10 Yet, while he charged his opponents with “all the crimes in history except the Crucifixion of Christ, about the perpetration of which offense he seemed a little doubtful,”11 the Ventura Democrat felt that Vandever did not adequately deal with the long-lived anti-Chinese question, the perplexing silver issue, harbor development, reclamation of desert regions, liberalization of land laws and various labor problems, all intimately vital to southern Californians.12 The Republican-oriented Ventura Free Press, however, said such attacks on Vandever sounded “like the hiss of a copperhead…”13

Joseph D. Lynch was certainly as colorful a contender as was the aging warrior. Born sixteen years later than Vandever, Lynch was a Pennsylvanian who had studied for the priesthood before turning to literary pursuits and becoming an able New York journalist. In the early 1870s he moved to San Diego to be Editor of the World before coming to Los Angeles in 1875. The fleshy, energetic Lynch could turn ill-tempered as was demonstrated in 1879 when he got into a shooting affray with a fellow Angeleno newspaperman, William A. Spalding. After a vitriolic duel on the printed page Spalding realized that a showdown was likely. Lynch always carried a hip-pocket gun; so, when they met on the street that August 16, Spalding drew first and fired, but the inaccuracy of his pistol avoided bloodshed, while Lynch’s three shots went wild.14

After ten years as owner of the Los Angeles Herald, Lynch began to develop the organ in 1886 as “a formidable bulwark for the Democracy.”15 That fall he ran against Vandever. The election results were very close. At first count Vandever had 14,085 votes to 13,587 for Lynch, but a later report showed the Republican’s majority had dwindled to only 56 votes.16 Lynch contested the election which went to the House of Representatives’ committee on elections and dragged on there until April 26, 1888 when that body, despite the Democratic majority in the House, unanimously reported in favor of Vandever’s retaining his seat. Unsure of his position for more than half his first term, William Vandever was occupied by a troublesome, expensive contest. Conditions were much more favorable in 1888 when he sought reelection, for that autumn the nation went Republican, electing a G.O.P. Congress and President Benjamin Harrison. Vandever ran against a young, inexperienced Democrat, R. B. Terry, and was returned to office by a solid majority of 7,000 votes.18

Once his first election was validated, Congressman Vandever became a leading exponent of state division, a movement not new to southern California. Shortly after state¬hood in the 1850s Americanos and Hispanic Californios of the region first sought separation of the area below Point Conception, for the gold rush had made their homeland vastly different from the north. Until the 1880s southern California was sparsely populated, typified by cattle ranching and a Hispanic culture and saddled with heavy real estate taxes; while northern California possessed political control, impressive urban and mining development and the state’s capital and prestige. Southlanders found travel to that capital slow and expensive, and were convinced that they would get more benefits through separation as a territory and eventual statehood. The war had deflected attention from the issue, but in the eighties, it took on new life. Not from local backwardness this time, but because of recent growth in land promotion, industry, agriculture and population, southern California sought a divorce from the privileged north. Promoters and proud residents felt that the “Southland” now had the people and the wealth to support statehood, while climate, terrain, economy, and sentiments distinguished their region. Foes of the movement accused Congressman Vandever of favoring the locally popular cause to further his political ambitions, perhaps for a United States Senate seat, saying he would attract more attention through this scheme than any other. Witty editors dubbed his proposed South California “the State of Vandever.”19

On December 5, 1888 Representative Vandever introduced a bill in the House which would have given Congressional consent to dividing California from the northeast line of Alpine County (adjacent to Nevada just below Lake Tahoe) and running southwesterly along the northern boundaries of Tuolumne, Merced, San Benito and Monterey Counties to the sea. Californians then would have had the opportunity to vote on the issue.20 Defending his bill on December 12, Vandever asserted that San Francisco through corrupt methods virtually controlled state politics and federal patronage and held the balance of power in both of California’s political parties. He predicted that Bay Area representatives in Congress would never support his region’s needs, now urgently increasing as its population and economy grew. “In Congress I have five of her delegates to oppose me on all propositions for improvements of our harbor,” he declared.21 The railroads, favorite villains of California reformers of that period, would see their great powers neutralized by state division, Vandever rationalized. Democrats, however, feared division would produce another Republican state at a time when three of the four already proposed new states were Republican territories! They realized that southern California since the spectacular Boom of the Eighties had experienced a great influx of Midwesterners, mostly Republicans. Meanwhile Vandever admitted to reporters that, although his bill had been tabled by Congress, he believed that its mere introduction would rouse public sentiments which eventually would bring victory.22

At home, the Ventura Democrat tried to show what Pandora-like perils might be hidden in his scheme. It quoted the prestigious San Francisco Alta California:

And now Nevada wants a slice of California. Vandever has stuck his fork in the breastbone of this State and is whetting his carving knife in the attitude of a host who asks all the States and Territories, “What is your preference, white meat or dark: any of the stuffing?” Los Angeles wants the San Joaquin Valley up to the Stanislaus line and Nevada wants the Sierra Nevada Mountains. Now let Oregon pass her plate for the rest of us. The discussion so far belittles and disgraces the State and makes a true Californian tingle with indignation while he is not blushing with shame.”23

Even earlier Vandever had become interested in a scheme to purchase Baja California from Mexico, and was proposing the economic development of Ensenada. By late 1889 he called for a joint resolution empowering the American president to negotiate with Mexico for this purpose. The additional territory open to Western speculators would have given his proposed State of South California (with its capital at Los Angeles!) enough territory and population for an impressively large state and thus have justified its being severed from Sacramento’s authority. 24 This plan, too, failed despite much enthusiasm both for and against it in Los Angeles. A filibustering expedition against Lower California at the time complicated the problem. Ever skeptical, the Ventura Democrat assayed the situation:

Our stupid and pompous old congressman divides his time between haunting the departments [at Washington] in the interest of office hunters, and formulating a bill for the annexation of Lower California — an impractical scheme engineered by speculators and adventurers who have bribed or humbugged him into their service.25

Although the Hollister Advocate in the northern part of his district was not alone in calling Vandever “a worthless stick of political timber,” he accomplished several worthwhile things for his scattered constituents. Representative of a section ever conscious of maritime commerce, he worked for harbor improvements at San Diego, San Pedro and Santa Barbara, and introduced a bill appropriating $100,000 for the creation of a harbor at Ventura.26 In 1890 he successfully proposed bills establishing Yosemite, Sequoia, and General Grant National Parks, enacted September 25 and October 1 of that year. The Los Angeles Express rightly called this “a magnificent heritage to posterity,” for which John Muir had long struggled. In commemoration of his efforts, 11,800-foot Mount Vandever in the High Sierra was soon named for him.27

Despite the fact that in 1888 his fellow Republicans represented a minority in Congress and federal patronage seekers ruled the Post Office Department under President Cleveland, Vandever worked hard to get appropriations for southern California’s mail. An observer that year said that he made almost daily visits to the department where he appealed for relief “and has introduced bill after bill and had them referred to committees, and has followed them up and urged their favorable consideration.” Some relief came, but not enough to satisfy Californians who complained that appropriations were inadequate.28 Vandever also supported a victorious endeavor to have California’s “own” General John C. Fremont granted a pension shortly before the “Pathfinder’s” death in 1890; but Vandever angered many southlanders by favoring St. Louis over Chicago, origin of many of them, as site of the World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893 (Chicago won anyway).29

In the fall of 1890, the aging politician was no longer boosted as a Republican candidate to succeed himself. Even the Los Angeles Times which had defended him in the campaigns of 1886 and 1888 was displeased that he had obtained only $35,000 to improve San Pedro harbor, noted that he had made many unfulfilled promises and did not like his state division campaign which had divided southern Californians more than it actually threatened to divide the state. His Baja California scheme also seemed to threaten America’s improving relations with Mexico.30 Others were disappointed that he had not sponsored national irrigation for a thirsty Southwest. Actually, their premature cries did not bring action until Theodore Roosevelt’s era.

In an age of corruption, charges were made against even this hero, but without any evidence, that he had been involved in fraud. Even the super-critical Ventura Democrat insisted, “We are not prepared to believe that he is wantonly corrupt or dishonest.”31 In 1891 Vandever left office. At first, he probably hoped for a third term despite little popular enthusiasm for it. A younger man was desired and one more active. The San Diego Sun complained that his name was seldom seen in the eastern press or the Congressional Record. On June 4, 1890 he formally announced he would not seek renomination. The Republicans chose William W. Bowers who won Vandever’s seat that November.32

Already ailing when he left office at age 74, William Vandever died of heart disease at Ventura on July 23, 1893. After a Presbyterian service and G.A.R. ceremonies his remains were interred in the Ventura Cemetery. He left a widow, one son and two daughters.33

With over eighty years of hindsight, it seems safe to say that Vandever did his best. Hard-working, serious, honest, sincere, well-liked in his adopted state, he attracted much criticism, however. Most of his shortcomings were unavoidable, for he served southern California during its first rapid growth when an impatient public was boosting overblown expectations and making grandiose boasts. Much of his four-year tenure in Washington was clouded by a disputed election while he served in a Congress controlled by a rival party. Meanwhile, California’s other five House members, representing the north, offered him little cooperation and considerable malice! Southern California’s towns, then suffering from such a regional “chauvinism” in their rivalries with each other for government favors, would have perplexed King Solomon himself had he tried to serve their objectives! So short a residence in the region prior to his election did not help Vandever either. His achievements, then, seem more distinguished when we see what had to be overcome. And his coming to political power was symbolic of his county’s and region’s significant political future. By the turn of the century, Ventura County would send a United States senator to Washington.

Footnotes

- “Major General William Vandever,” Annals of Iowa (Des Moines) I, October 1893, 236-237. As an Illinois resident Editor Vandever had tirelessly supported railroad building in that frontier state. See also: The past and present of Rock Island County, Ill. (Chicago, H. F. Kitt & Co., 1877) 156-157.

- He married a Miss Williams of Davenport, Iowa.

- F. I. Herriot, “Iowa and the first nomination of Abraham Lincoln,” Annals of Iowa, VIII, October 1907, 205 and 208. In Iowa Vandever was accused of supporting the anti-foreign Know Nothing Party, but publicly stated that he did not oppose foreigners nor did he want naturalization laws stricter. His constituency in Iowa contained many French, German, Irish and Swiss-born voters.

- John E. Briggs, “The enlistment of Iowa troops during the Civil War,” Iowa Journal of History and Politics (Iowa City) XV, July 1917, 345 and also Edward H. Stiles, Recollections and sketches of notable lawyers and public men of early Iowa ( Des Moines, Homestead Publishing Company, 1916) 132-134.

- Ventura Daily Free Press, September 5, 1887, p. 2.

- David L. Phillips, Letters from California (Springfield, Illinois State Journal Company, 1877) 97-99. The incorruptible Vandever meanwhile was trying to find new homes for the remaining Mission Indians of California.

- Ventura Daily Free Press, October 4, 1886, p. 1.

- Ventura Democrat, October 28, 1886, p. 2.

- Ibid, October 21, 1886, p. 2.

- Op. cit.

- Ibid, September 30, 1886, p. 3.

- Ventura Free Press, August 18, 1886, p, 2; and Ventura Democrat, October 28, 1886, p. l; and Los Angeles Times, October 29, 1886, p. 4.

- Ventura Free Press, September 2, 1886, p. 2.

- “The shooting affray at Los Angeles,” San Francisco Alta California, August 19, 1897, p. 1. For a fuller discussion of Lynch, see William Andrew Spalding, Los Angeles newspaperman; an autobiographical account ed. by Robert V. Hine (San Marino, Huntington Library, 1961) 89-90 and 100-103.

- Harris Newmark, Sixty years in Southern California, 1853-1913 (New York, Knickerbocker Press, 1916) 516 and 556.

- Ventura Free Press, November 8, 1886, p. 2.

- Ventura Free Press, May 12, 1888, p. 2 and Ventura Weekly Democrat, April 26, 1882, p. 2. See Joseph D. Lynch vs. Vandever, William, Contested election case of (Washington, Government Printing Office, 1887).

- Ventura Free press, November 10, 1888, p. 1 and “General William Vandever,” Los Angeles Times October 17, 1888, p. 4.

- Ventura Free Press, January 21, 1889, p. 2 and January 26, 1889, p. 2.

- San Francisco Call, December 6, 1888, p. 1.

- New York Times, December 31, 1888, p. 4. See also Ventura Free Press, December 20, 1888, p. 2.

- A good survey of southern California’s rapid change and future hopes is found in Glenn S. Dumke, The boom of the eighties in Southern California (San Marino, Huntington Library, 1944). He deals with state division at this time on pages 271-272. See also “To divide or not?,” Los Angeles Times, December 8, 1888, p. 2.

- Ventura Democrat, December 20, 1888, p. 2.

- “Californians on important House committees,” Los Angeles Times, December 18, 1889, p. 4 and Ventura Free Press, July 21, 1887, p. 2. For an interesting treatment of contemporary moves to acquire Baja California, see Anna Marie Hager, ed., The Filibusters of 1890: The Captain John F. Janes and Lower California newspaper reports (Los Angeles, Dawson’s Book Shop, 1968).

- Ventura Democrat, January 16, 1890, p. 2.

- Ventura Free Press, February 5, 1888, p. 2 and May 13, 1889, p. 2; and Los Angeles Express, July 24, 1893, p. 4.

- Los Angeles Express, June 6, 1890, p. 4; William Frederic Bade, ed., The life and letters of John Muir (2 vols., Boston and New York, Houghton Mifflin Company, 1924) II, 234; Francis P. Farquhar, “Exploration of the Sierra Nevada,” California Historical Society quarterly, IV, March 1925, 44; and Farquhar, comp., “Place names of the High Sierra, Part III,” Sierra Club bulletin (San Francisco) XII, 1925, 140.

- Los Angeles Times, March 4, 1888, p. 4 and May 28, 1890, p. 2; and Ventura Free Press, February 23, 1888, p. 2.

- Ventura Democrat, March 20, 1890, p. 2.

- Los Angeles Times, May 28, 1890, p. 4.

- Ventura Democrat, October 31, 1889, p. 2.

- Los Angeles Times, May 27, 1890, p. i; May 29, p. 2; May 31, p. 4; and June 5, p. 1.

- Ventura Democrat, July 28, 1893, p. 3 and Ventura Free Press, July 28, 1893, p. 4. Vandever died in modest circumstances. After several setbacks, Col. David B. Henderson, his friend in Congress, finally got a pension for Vandever’s widow, who had helped nurse sick and wounded of both Union and Confederate sides during the war. Edward H. Stiles, op. cit., 152-153.