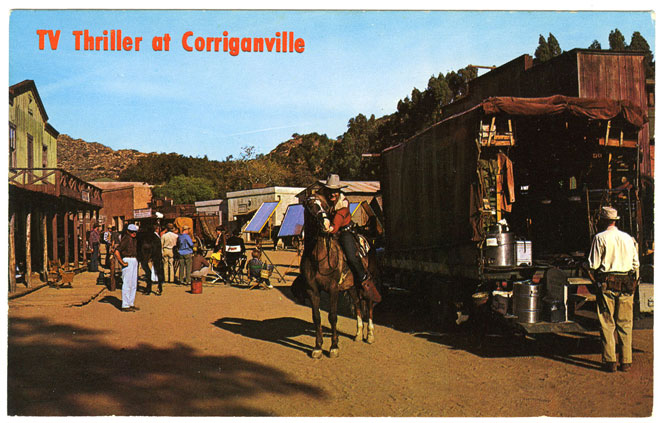

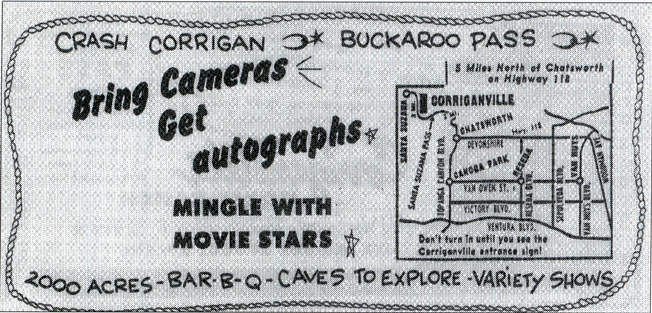

Did you know that Ventura County once hosted its own version of Knott’s Berry Farm? In this month’s Journal Flashback we’re sharing the story of Corriganville, which in fact predates Knott’s Berry Farm by a few years. The ranch served as both a popular amusement park and filming location. Owned and run by the colorful stuntman Western actor “Crash” Corrigan, the park offered a generation of Californians Western-theme entertainments until it was sold in the late 1960s. The site is now a public park that includes several hiking trails where numerous Westerns were filmed. The Park can be reached via the 118 freeway and Exit 30 for Kuehner Drive.

May 1999 commemorates the Fiftieth Anniversary of the public’s first view beyond the wagon wheel gates of the Ray Corrigan Movie Ranch in eastern Simi Valley, a tilted landscape of weathered rock, accentuated by huge boulders fringed by groves of coastal and California live oaks, and surrounded by artesian springs and long-traveled byways. A historic Southern California landscape? A Hollywood dreamscape? Both. History, legend and fantasy all came together at the Ray Corrigan Movie Ranch, known to the public as “Corriganville.”

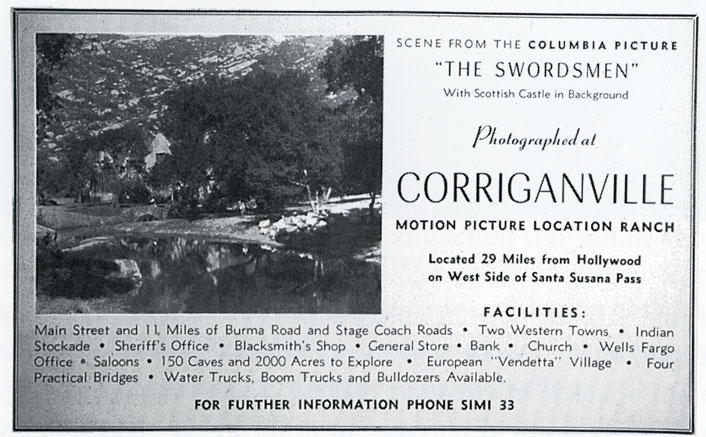

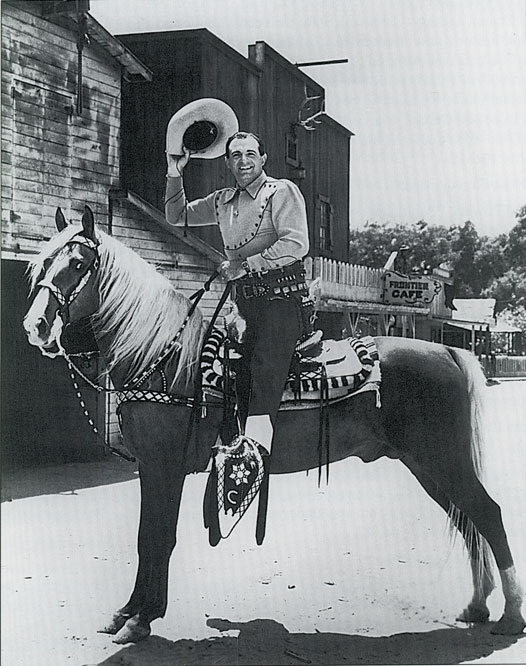

One of approximately forty movie ranches in Southern California that regularly provided scenery and sets for Hollywood’s classic movies and television productions, Corriganville was the only movie ranch that allowed the public to view its operations. Popular western movie hero Ray “Crash” Corrigan provided scheduled western entertainment that drew large crowds. Corriganville became as well known as Knott’s Berry Farm, attracting visitors from across the nation and even from overseas.

The founder and namesake of Corriganville was born Ray (not Raymond) Benard in a cottage on the grounds of the Joseph Schlitz Brewery Company in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, on February 14, 1902. Here, his father, Bernard A. Benard, served as caretaker. “Bernie,” his wife, Ida, and Ray eventually moved west to Denver, Colorado. By the age of fourteen, Ray Benard was working at a furniture company while studying electronics. He would later have his own electrical business where he experimented with and subsequently developed a number of electrical products. Eventually, he would hold patents on more than twenty electrical inventions.

Ray Corrigan arrived in Hollywood from Denver in 1922, looking not for work in one of the film studios, but rather for Bernarr Macfadden, the naturist, who ran the Hollywood Gym and who printed publications on naturalistic health and body building.1 Ray had a noticeable double curvature of the spine that detracted from his appearance, causing a loss of height and hampering his mobility. Macfadden had been successful in treating this condition in young men. After a year’s course from Macfadden, Ray had the physique of a front-cover Adonis. In order to afford his correctional treatments, Ray worked for a while in Long Beach as a real estate salesman. He temporarily owned a block-sized area of Signal Hill, but sold it before its oil potential was realized. His broker, John Mills, had real estate transactions with the legendary Wyatt Earp.2

Now a capable body-builder in his own right, Ray worked for Macfadden as a director-trainer and was later invited to work at Metro Goldwyn Mayer Studio’s gymnasium, improving the appearance of valuable movie stars and starlets like Ruth Chatterton, Joan Blondell, Joan Crawford and Dolores Del Rio. Del Rio had experienced a lengthy bout of depression that threatened her contract with MGM. The studio decided she should take Ray’s naturalistic health exercises. This therapy seemed to work. As Dolores emerged from her doldrums and returned to acting. It was her husband, MGM’s art director, Cedric Gibbons, who gave Ray a two-year contract as a stunt man. Ray was no stranger to the play-acting environment. He had been involved with local theater in Denver and had chosen to participate again at the Hollywood Community Theatre while working with Macfadden. Ray’s parents had moved to Hollywood, where his father procured a job at Western Costume Company.3

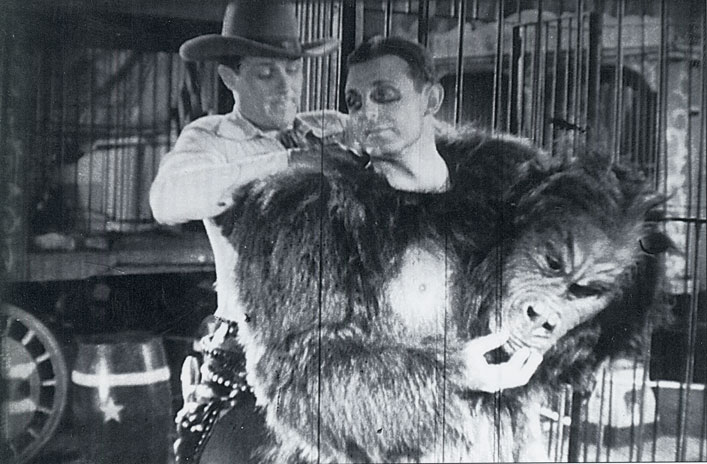

At the beginning of his career as a movie stunt specialist at MGM Studios, he kept the name Ray Benard.4 During this same time jungle adventure movies were gaining popularity. King Kong (1933) whet the public appetite for movies in this vein.5 Consequently, from 1934 until 1954, part of Ray’s Hollywood heritage was to portray gorillas in adventure, comedy and horror movies. To do this, he needed a strong, muscular physique. Ray spent his free time in early 1934 studying the mannerisms of larger primates at the San Diego Zoo. Shortly thereafter, Ray Benard/Corrigan was encased in the hot and stifling interior of one of his five expensive, handmade gorilla suits, aping his way through classic Hollywood features. (His name was missing from the cast of characters in these features. It would have detracted, he believed, from his role as a Western hero.) In two films, Come On, Cowboys (Republic, May 1937) and Three Texas Steers (Republic, May 1939), Ray appeared as both ape and hero. Corrigan “monkeyed around” all through the 1940s and 1950s, playing a hairy opponent to the likes of Boris Karloff and the Three Stooges.6

Ray stunted in thirty-one movies for MGM. He first accomplished aerial vine-swinging and underwater rubber alligator wrestling scenes for the studio, leaving Tarzan’s Johnny Weissmuller the surface-swimming chores. For MGM’s Mutiny on the Bounty (November 1935), Ray fell off a ship’s high yardarm, a stunt that killed an actor on a previous attempt.7

After his two-year MGM contract expired, Ray soon evolved into supporting roles and later leading actor roles in budget adventure movies and serials for other studios. Prior to his promotion by Republic Studios to a Saturday matinee Western movie hero in September 1936, he filled a supporting role in the Gene Autry Western, The Singing Vagabond (Republic, December 1935) filmed at the Iverson Movie Ranch in Chatsworth—located on the east side of Santa Susana Pass. During a break in the filming, Ray’s friend, actor Clark Gable from MGM, arrived to take him hunting. The duo proceeded west, over the pass. Ray had his first look at the Jonathan R. Scott cattle ranch at the foot of the Santa Susana (west) side of the grade. He saw past the clutter residents of the San Fernando Valley had deposited there and envisioned an active movie ranch that could equal or out-perform the neighboring Iverson Ranch location, which had had its beginnings twenty-five years earlier. Ray noticed that the unusual and dramatic geological formations of the Scott ranch were similar to the formations on the Iverson property—features that attracted the film studios. The ranch was for sale at $11,354, and Ray paid $1,000 down, plus payments of $1,000 a month. He then began clearing away the debris. An era of Hollywood movie ranch history and, eventually of rare public entertainment was about to begin.8

CORRIGANVILLE

Art often imitates life in Hollywood. Many feel it even exceeds and leads. Eastern Ventura County embraced this scenic location where fable repeatedly embellished historical fact and left a public record for all to see: hundreds of movies and thousands of television episodes, along with a myriad of live Western stunt show reenactments—all were created at the Ray “Crash” Corrigan Movie Ranch, later known as the Corriganville Movie Ranch.

Around, through and over the endless boulders, rock-falls, caves and cliffs, good guys and bad guys confronted each other at the ranch, almost never stopping to reload their six-guns. Indian tepees circled the shore of Corriganville’s placid lake adjacent to a five-acre oak forest. At other times, the forest would echo with the sounds of cavaliers or cowboys doing battle. The many trails of the picturesque ranch were pounded to dust as groups of horsemen, stagecoaches, wagons and other conveyances went around and around in front of cameras. Well trained stunt men would tumble off roofs or “bite the dust” in front of a wide-eyed public, setting a precedent for future historical reenactments throughout the western states.

THE PAST AS PROLOGUE

Long before the establishment of the Spanish El Camino Real or the Yankee stage lines that followed, the sheltered grounds had appealed to the native inhabitants of the region. Several Chumash sites have been located on the ranch property. With the arrival of Spanish inhabitants, the area would become part of the land grant known as San Jose de Gracia de Simi, first granted in 1795.9

In the same way that New England states boast about the number of places where George Washington purportedly slept, Central and Southern California can recount ad infinitum locations where the notorious Tiburcio Vasquez (1835- 1875) and his fellow bandits were said to have hidden and buried their treasure. Legend says Corriganville was one of these locations.10 Its protected location at the east end of the ten-mile-long Simi Valley, tightly bordered by the Santa Susana Mountains and the Simi Hills, and adjacent to a dense oak forest with nearby artesian springs, made an ideal retreat for bandits threatening travelers on the Camino Real route between the missions of San Fernando del Rey and San Buenaventura.

Tiburcio Vasquez was said to have visited Larry’s Stage Station, or the Mountain Station, on the west side of the steep and rocky Santa Susana Pass. Proprietor Lawrence Howard, an Irishman whose resourcefulness and survival instincts matched the nefarious intensity of the cutthroats, thieves, murderers and desperadoes who shadowed these stage stations of the Coast Lines, once purportedly placed a woman passenger, her baby, and her driver out of harm’s way late on a spring night in 1871. Larry bedded them down with blankets and pillows in a corner of the front yard under the oaks, in spite of their entreaties to use the comforts of the inn. About midnight, Vasquez and his company of bandits rode noisily into the yard. They dismounted and went directly into the inn. Afraid of discovery, the fearful travelers gathered horse and buggy hastily and fled away in the darkness, up and over the pass toward Encino, thankful for their lives. The site of Larry’s Station was later included in early Western action at the movie ranch.11

The Coast Line stage road (1861-1875) approximated the route of El Camino Real after the outbreak of the Civil War, at which time the southerly Butterfield Overland stage route, which ran from Tipton, Missouri, to San Diego, was closed. After that, mail, newspapers and freight transported by Wells Fargo & Company came from the north via the new Butterfield Overland terminus located at Placerville. The route over the rocky Santa Susana Pass, located between San Fernando and San Buenaventura, was no more than a horse and foot trail until a vehicle road was blasted through to accommodate the Coast Line stagecoaches.12

Where Jonathan Scott had once grazed his livestock, Ray Corrigan kept about thirty-five head of Hereford cattle on his movie ranch as one of many conveniences for the studios. Leo Carrillo, who frequently filmed “Cisco Kid” episodes at Corriganville, recounted that his brother, Edward (Jack) Carrillo, an assistant engineer and foreman for the Southern Pacific Railroad, had blasted the tunnel under the Santa Susana Pass at the turn of the century with a Chinese work crew – a dangerous task that took four years to complete. The western exit of the tunnel bordered the southern edge of Corrigan’s ranch, just north of the site of Larry’s Station.13

Still another blend of history and Hollywood involved the Jonathan R. Scott ranch house. Ray and his second wife,14 the former Rita Jane Smeal, made it their residence in mid-1938. All three of their children were born there: Tommy Ray on July 7, 1944, Joyce Christine on July 10, 1945, and Patricia Ann on July 12, 1946. (When the children were young, their collective birthdays were celebrated on July 7.) The ranch house was the western-most building of the Silvertown movie street. While the children played, Hollywood was recording their home on film as a stage depot, a telegraph office or a pony express way station, as well as a ranch house. The children would sometimes amuse themselves by discovering cowboy pistols left among the boulders during rigorous movie action scenes.

By the end of 1936, fledgling Republic Studio’s new Western film series featured three characters that reached the Saturday matinee theaters: Stoney Brooke, Tucson Smith and Lullaby Joslin; Ray Corrigan played Tucson Smith. Together they were the “Three Mesquiteers,” a parody of the famous Three Musketeers. Because of good production values, exciting and innovative story lines, and music that matched the action, the new series was an instant box office hit with kids across the country.

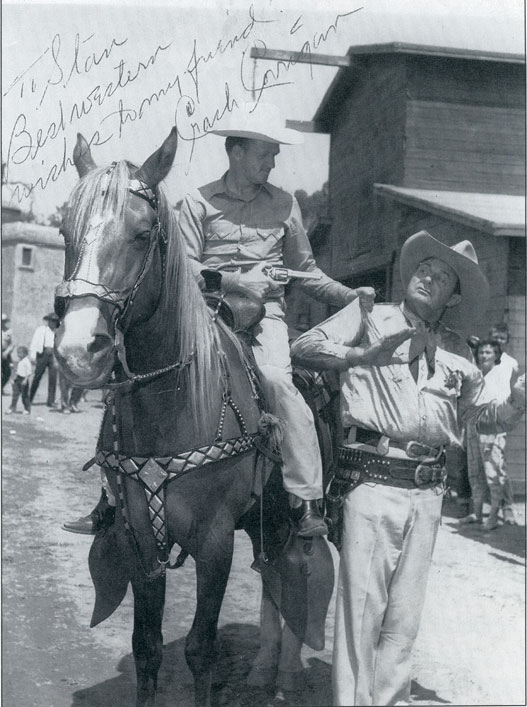

“CRASH” CORRIGAN

Earlier that year Ray Benard had legally changed his name to Ray Benard Corrigan with the success of his lead role in an Atlantean adventure serial titled Undersea Kingdom (Republic, May 1936). His character in the serial was named “Crash” Corrigan. It was Ray “Crash” Corrigan whose name now appeared on movie posters and lobby cards. Ray’s new public recognition and his Republic Studio contract permitted him to make personal stage appearances at theaters across America to promote his films. In the company of one or more Western entertainers, Ray would perform stunt routines, sometimes interacting with a movie screen image, and would tell how movies were made. Audiences turned out in large numbers. Theater managers were supportive, and Ray now had extra income to pay off his movie ranch. Ray continued these seasonal appearances between his filming schedules into 1943, while finishing out his contract with Monogram Studios as lead member of their Western trio series, the “Range Busters.” Ray was also sought out to endorse consumer products for national advertising. He was the first public figure to sponsor the breakfast cereal Wheaties.

In 1937, while on a late summer tour of the Eastern states with his future wife, Rita, Ray neglected to send in a scheduled ranch payment on time. With the contract thus violated, the ranch owner, a lawyer who had originally received the Scott property as payment for a debt, demanded an additional $3,600 or a forfeiture. This necessitated a scramble for extra funds (enter the agitato music with the action). Ray and his partner, cowboy singing star Eddie Dean, left Kentucky with the funds in hand, and drove nonstop to California in their abused and belabored Packard. They arrived at the ranch on the day payment was due, much after the fashion of a Western movie plot. Even Gene Autry came to the rescue with one hundred dollars.15

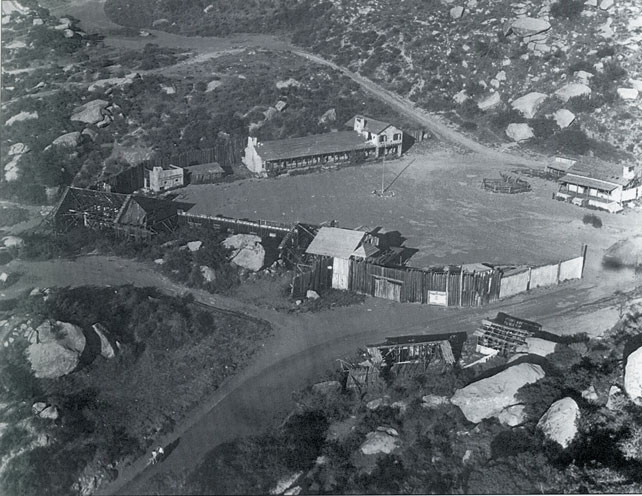

Title to the 1,829.74-acre ranch now belonged to Ray Corrigan.16 Raoul Walsh, assistant director to early motion picture producer D.W. Griffith, had filmed some one- and two-reel silent Westerns in 1912 among the rocks at the ranch, but Ray now set out to transform this former cattle ranch, stage stop, and purported bandit hideout into a major movie location that would be attractive to numerous Hollywood production companies.17

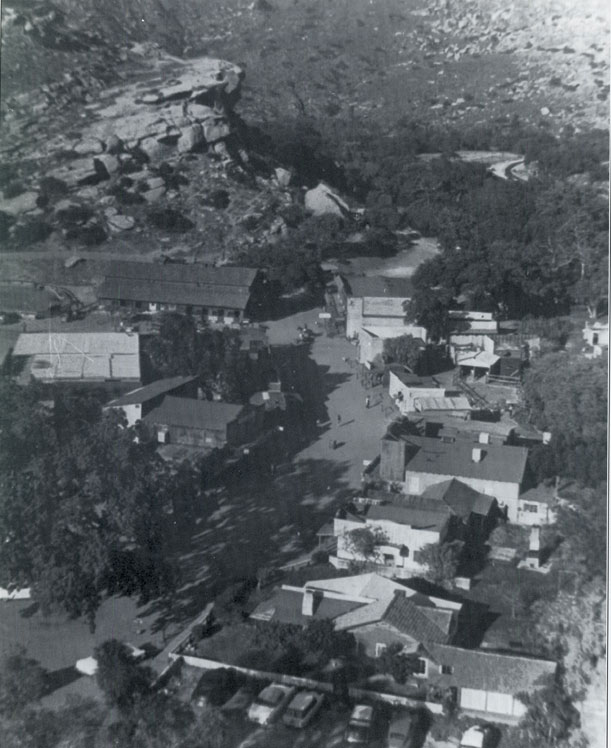

Ray hired the well-known firm of A.S. Grinnel Company of Los Angeles to lay out new roads and widen others. The bulldozers cleared rock and brush from Table Mountain, Ray’s name for the fifteen-acre plateau on which the Fort Apache set would one day be built.18 Ray also contracted with major studios over the years to construct semi-permanent sets on the ranch. The originating studio would have exclusive use of the set for a year. Thereafter, other studios could rent the set.

Columbia Studios was first. With Ray’s additional expertise as a gunite contractor, Columbia paid for the construction of an elongated body of water variously described as a lake, lagoon or swimming pool. The northwest edge of the lake featured a flat-topped diving rock that would allow a horse and rider or horse-drawn vehicle to approach from a higher slope behind the rock and plunge from its edge into the water. This rock was piped to provide a waterfall on demand. A recirculating stream fed by one of the original artesian wells supplied the lake. An arched, cement bridge crossed the lake end of the stream. Two movie trails forded the upper length of the stream. At the dam’s end, underwater viewing ports permitted cameras to film submerged action scenes. Ray had the Arroyo Simi below the dam cement-channeled to control seasonal run-off.

At the southwestern edge of the ranch, the Arroyo Simi was covered over to permit more room for an intended Western town and workshops for ranch maintenance. This was the most level area of the ranch. Ray constructed bunkhouses for workers and cowboys, and erected a large livery stable to accommodate movie horses, which he later rented to the public. Ordinary folk could ride the trails their Western heroes rode. Warner Brothers’ Studios helped trim the trees of the five-acre oak forest. Three “insert’” or running roads – over a mile in length – ran from the headquarters area into the oak forest, where the trails merged. Camera cars would travel a smoothly paved road while shooting the action on the dusty trail across the arroyo.19

The first movie filmed at the new Ray Corrigan Movie Ranch was RKO’s Gun Law starring George O’Brien, released in May 1938. Western movie nostalgia hobbyists, however, are certain earlier sound films were completed there while Ray was setting up operations. Corrigan had chosen a propitious time and place to organize his movie ranch. The high volume, theater-going habit of the American public, brought about by escapism laid at the door of the Great Depression, continued throughout the 1930s once the problems of introducing sound to movies had been solved. Two years, 1937 and 1939, were the peak attendance years for movies of that decade. The public sought the fast action adventure movies that Corrigan Ranch scenery was so good at supporting. With a little help from the studios, different parts of the ranch could resemble almost any location in the world: an island in the South Seas, an African jungle, the Burma Road, the Northwest woods, a Sonoran desert, the American West, a European forest, or a vista of green meadows by a sylvan lake. In addition, the ranch’s location close to Hollywood appealed to the budget-minded studios.20

No letdown in attendance by the movie-watching public occurred during most of the 1940s, although their motivation had changed to escape from the rigors of World War II. Some Westerns even had modernist Allied and Axis war plots woven into their scripts. The Ray Corrigan Movie Ranch was a busy, busy location during the war years. Corrigan could accommodate five different production companies at once. Knowing his ranch intimately, he could show the directors and cameramen where to get their desired scenes, from what angle, and at the best time of day. In doing this, the studios could economize and have much of their footage shot at Corrigan’s ranch, although most movies contained scenes from multiple outdoor locations.21

The income from his frequent gorilla roles permitted Ray to build the Western town that he envisioned for his ranch, one building at a time. Western buildings appeared in other areas of the ranch, but the first use of the ranch buildings was a Western movie street called Silvertown, which appeared during the 1943 filming year. The town continued to grow into the period when the public would be invited, sprouting useful interiors for public utilization, much like Walter Knott’s Ghost Town panorama.

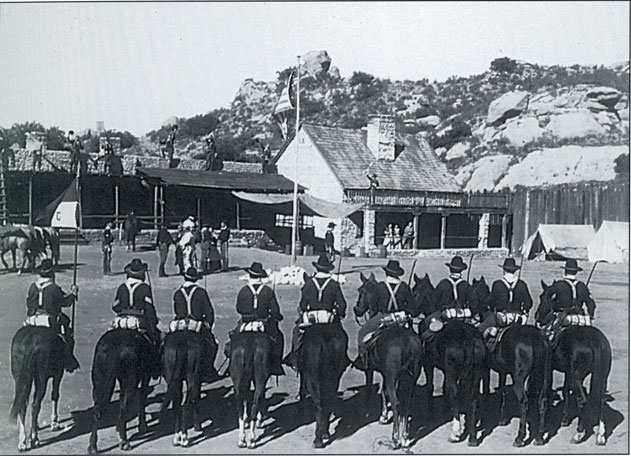

The large sets at the ranch were constructed in the mid- and late 1940s, before the public was admitted. Howard Hughes built an extensive Corsican peasant village for his movie Vendetta (RKO, filmed 1946, released March 1951) against the west edge of the ranch’s largest sandstone ridge, between the Table Mountain plateau and Silvertown, at a cost of $103,000. This set saw much usage as a “third world” village, facilitated by the changing of minor props. Director John Ford had his Fort Apache (RKO, May 1948) set constructed on the plateau at a cost of $65,000. A two-story Scottish manor house, appearing to be made of cut-stone and called the “Swordsman’s Castle,” was located in a meadow just north of the oaks, near the arched bridge. In the vicinity of “Tonto’s Cave,” along the south edge of the big sandstone ridge, there was once a large “Jungle Jim” pagan temple set, complete with papier-mache Banyan trees and trailing vines. Johnny Weissmuller fulfilled a number of Jungle Jim episodes at the ranch. The Bomba the Jungle Boy television series also used the ranch, but not one Tarzan movie was ever filmed at Corriganville – in spite of newspaper accounts to the contrary. For The Man from Colorado (Columbia, November 1948), a second complete Western town was constructed at the ranch, and then burned to the ground to satisfy the story line.22

Before the years of public access, Ray had a gaming room accessible to front-rank Hollywood stars such as George Raft. He also offered a dude ranch club membership to one hundred select members who had the use of sleeping facilities, a well-equipped private gymnasium, and an indoor barbecue pit and kitchen. Deer, rabbit, quail and pheasant resided within the borders of the ranch. Members could ride horses, swim, go hunting or use archery, rifle or skeet shooting ranges. These activities attracted Hollywood actors who wanted to “disappear” for a while.23

Attendance during the Golden Era of movies (1934-1955) peaked in 1946. After that year, movie production took a long, gradual downward slide. Budget films belied their name. They became too costly to produce for shrinking audiences. Quality Westerns from the ’30s and ’40s that were sold to television further depressed the market for new B Westerns. Hollywood’s professionals continued to be a mainstay of the California economy—down to our present day—but the circumstances surrounding that steadiness changed.

POSTWAR RECREATION & TELEVISION

Through federal anti-trust legislation, the dissolution of the old mogul system of studio autocracy took place about the time of the popularization of television. After World War II, the public had greater incentive to explore the out-of-doors. A recreation evolution took place: tent camping led to car beds, small travel trailers and station wagon camping, and then to the eventual introduction of the true recreational vehicle. By 1951, motorlogue travel guides reappeared in Los Angeles-area Sunday newspapers for the first time since the War. The little television screen slowly grew larger over the years, proportional to more sophisticated programming. The Saturday movie matinee phenomenon was to fade and disappear. Budget movies decreased in frequency, with color movies of an A- or B+ quality taking their place. Eventually, Hollywood did what it had to do – embrace television production.24

Ray Corrigan understood this shift towards television and prepared for it in two ways. He organized his ranch for the onslaught of numerous television production companies, and got ready to invite the public to see how movies and television sequences were made. Several major studio ranches in or near the thirty-mile limit from Hollywood—imposed by actors’ and technicians’ guilds—had the advantage of being able to afford their own technical production equipment. The newer, less-endowed television production companies did not always have this ready advantage. Ray made filming on his ranch more attractive by providing the necessary production equipment. Official Corriganville Ranch stationery—in this case a letter dated May 1, 1952—listed features that would entice production companies and also attract the public: complete sets, production facilities and sound stage, Western street, Mexican street, Western fort, Spanish village, country church (and school), Robin Hood Lake, Robin Hood Forest, insert roads, jungle, caves, six miles of Burma Road and meadows, hideout cabins, ranch house, twenty hotel rooms, restaurant (90 seats), chuck wagons, trading post, Western merchandise, a thirty-horse barn, saddle horses, lighting (1500 amps), machine shop, woodworking mill, portable generators, crane boom trucks, powered water trucks, fire trucks, motor grader, skip loaders, bulldozers, and camera cars. Ray also designed and built an aluminum food-catering trailer to use on location at the ranch. By contrast, all that the neighboring, long-time popular Iverson Movie Ranch could offer in the way of equipment was … a water wagon. (Even in a Western, there could be too much dust.)25 Ray charged each film company $650 a day for the use of his ranch. By checking the new movie production schedules conveniently listed in the Daily Variety and The Hollywood Reporter, Ray noted that nearly half of all Hollywood Westerns filmed between 1937 and 1951 had logged in at the Corrigan Movie Ranch.

Corriganville was first and foremost a movie ranch and continued as such to the end of its working days. Ray realized that frequent visitors to Southern California had universally expressed disappointment at not being able to view the inside workings of a Hollywood studio. Visitors at Universal Studios during the Silent Movie Era could make all the noise they wanted, eating their 25-cent box lunches. That is, until the studio evicted them in 1928 with the advent of sound. Tourists would not re-enter Universal until 1964, when the studio reopened for modest tours. During this thirty-six year interval, not one studio or movie ranch permitted the public to view its interior operations until Corrigan decided to invite them to his ranch. If Hollywood would drive out to Corriganville, so would tourists and Southern Californians for such a privileged opportunity.26

Ray Corrigan, like Walter Knott, kept adding to his Western town—Ray, for the production companies and later for the public, Walter, for his chicken dinner patrons. Neither Corrigan nor Knott clearly realized their operations were becoming amusement or theme parks. Today’s corporate Knott’s Berry Farm claims to be the world’s first public theme park.27 If spokespersons were available for the now defunct Corriganville Movie Ranch, they could more authoritatively make that same claim. Knott’s bases its claim on the positioning of a pioneer hotel building from Prescott, Arizona behind its restaurant in 1940, rather than the opening of the restaurant or the purchase of their farm.28 Corrigan’s Western town began with the livery stable he erected in 1937, or even with the earlier ranch house. Corrigan was first to enclose his property, charge general admission, provide rides, and add various entertainments and activities. Corrigan also showed a special sensitivity for the disadvantaged, and entertained busloads of physically and mentally challenged children at the ranch. Ray had a special regard for children with disabilities due to his own prior physical problems.

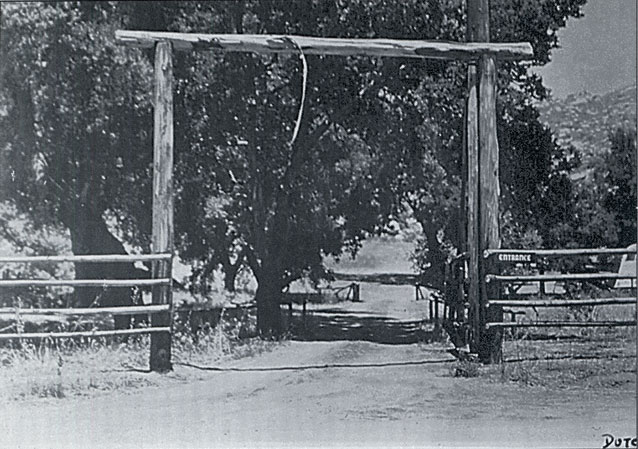

Ray decided to open his wrought-iron wagon wheel gates at the end of Smith Road to the public on May 1, 1949. He renamed the acreage the Corriganville Movie Ranch. On opening day—always a Sunday at first—the ranch was inundated with hundreds of cars, due to advance promotion that offered free admission with the presentation of a specially printed Dixie Cup ice cream lid. Ray had to turn many visitors away. Additional parking areas were marked out around the Western town in a spring 1950 refurbishing. As many as ten thousand visitors on a Sunday became normal, running as high as twenty thousand for special events. In May 1953, Corrigan purchased the sixty-acre Touvin Ranch, just south of the Hall Turkey Ranch, increasing the ranch size to 2,000 acres. This gave him frontage on Los Angeles Avenue, now Kuehner Drive. The addition provided room for a five-lane entrance gate, unpaved parking for twenty thousand cars, and room left over for the construction of a rodeo arena, grandstand seating for four thousand, and a food concession.29

The arena scheduled not only rodeos, but also Wild West, equestrian stunt and horse shows. Ray would have celebrity Western actors appear as Grand Marshals for each rodeo parade. Ray’s earlier experience with the Los Angeles-based Clyde Beatty Circus (1943-1954), where he performed equestrian stunts as a cowboy hero, as well as impersonating a “trained” ape, had made the versatile stunt man quite a showman.30 The stunts at the arena included rescues from a burning stagecoach in motion, transfers, falls and remounts from a runaway stage, and an Apache flaming arrow attack on covered wagons. The Sunday afternoon rodeo was broadcast from Los Angeles television station KNBH in 1953 under the title “Crash Corrigan’s Round-Up.” Two earlier television shows organized by Ray were “Crash Corrigan’s Ranch” (KECA, summer 1950), a weekly children’s show, and “Crash Corrigan” (KTTV, April 1951), on which his son, Tommy, appeared. With the advent of the rodeo shows, Ray invited the public in on Saturdays as well. Corrigan had a large billboard image of the Silvertown Western street mounted next to the ticket office over the ranch entrance. It was captioned at the bottom for all to see: “Through these gates pass the world’s most famous people.”31

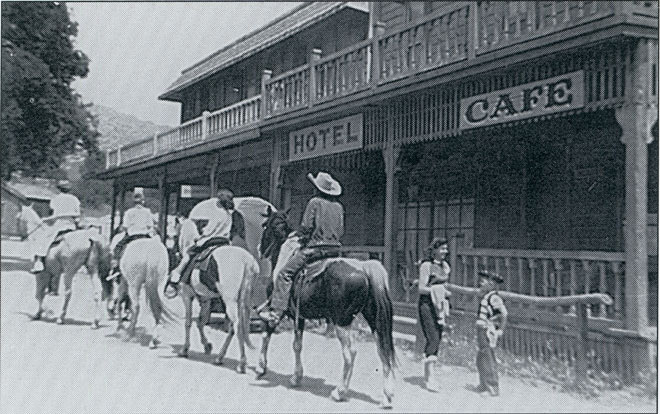

Tractor or horse-drawn trams and eventually buses were waiting at the parking lot staging area to bring visitors into the interior of the ranch. You could stay on for the grand tour or be deposited at major sites around the ranch. There was much to see and do at Silvertown. Ray kept a cadre of stunt men employed at the ranch to provide live thrills for visitors who now had a steady diet of television Westerns. They acted out stories from the Old West on Silvertown’s Main Street in scenes that were choreographed and performed to a taped narration, every half-hour, all day long. These performances have inspired countless Western reenactment stunt shows ever since.

Ray’s third wife, formerly Elaine Zazueta DuPont and today Elaine Calhoun, was heavily involved in the ranch’s entertainment schedule from 1952 until Corrigan sold out in 1965. (Elaine also managed an acting career in both movies and television.) She recalls that forty different stunt routines were catalogued.32 A typical day’s program in the ranch’s newspaper, The Corriganville Gazette, would look like this: “Dalton brothers’ bank holdup at Coffeyville,” “the beating of Joaquin Murietta,” “Billy the Kid becomes an outlaw,” “gunfight at the O.K. Corral,” “the hanging of Henry Plummer,” “the shooting of Belle Starr,” “the killing of Bill Tilghman,” “Billy the Kid breaks jail,” “Doc Holiday in Colorado,” “the Johnson County cattle war,” interspersed with movie plot stunts, fights, pistol twirling, rope drags and roof falls. Ranch advertising announced, “The Last of the Old West.” In the early 1950s, Western “old timers” from Knott’s Berry Farm came to Corriganville to learn stunt routines.33

Silvertown was thought out in a manner akin to Knott’s Ghost Town. Some buildings had Old West fake frontage, with the majority containing merchandising interiors to accommodate the public. A special 1962 edition of The Corriganville Gazette detailed what to expect: “Silver Dollar Saloon…draft beer, soft drinks, .05 cent salami sandwiches and performing dance hall girls; Last Frontier Cafe…quality food, reasonable prices, eat with the stars; Photo Shop… ‘have your pitcher took’ with movie and TV stars; Trading Post…Western wear, novelties, souvenirs, leather craftsman and glass blower; The Corriganville Gazette’s Newspaper Office…your name in headlines; Country (general) Store…assorted merchandising, auction, live Western music, Max Terhune and his dummy show; Merchandising Outlet novelty shop…with grandma and grandpa; and Chuck Wagons…snacks and drinks.”34 In addition, there was a blacksmith’s shop, hotel/soundstage with production numbers and public dancing, old-time movie theatre, a cafeteria, a photographer’s supply shop, a gunsmith shop with a gun collection, and an undertaker’s parlor and hanging tree. At the east end of town sat a double purpose church-schoolhouse, depending upon which end of the building was being filmed. Disguised bathrooms were available at both ends of town.

The Gazette listed features apart from the Western town buildings including: “the Livery Stable and Corriganville Fun Corral…most unusual Western rides in the world; Wells Fargo Stage Line, the Corriganville Express…departing every hour; The Frontier Railroad Company’s C.P Huntington locomotive and cars…1 ½ miles of scenic ride from Silvertown to Robin Hood Lake, over deep canyons, through the giant oaks of Robin Hood Forest; Robin Hood Lake and Forest area… hundreds of picnic tables with barbecue pits and broilers, plus other picnic sites around the ranch.” Ray rotated and updated the instrumentalists, singing groups and guest performers that were billed at Corriganville. Music was provided for ballroom, country western and square dancing. Ray also provided singing engagements for his ranch performers at other locations in the Los Angeles Basin.35

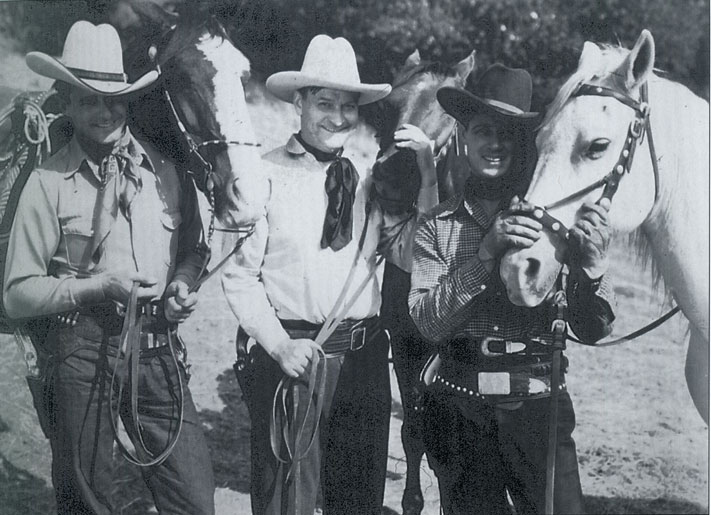

In addition, there were eleven miles of hiking and riding trails at Corriganville. Visitors could explore the caves, find planted arrowheads, view movie sets and hideout cabins, and sometimes see location filming. Youngsters could pose for one-dollar pictures with “Crash” Corrigan, hold his six-shooters, and sit on his horse “Flash.” “Crash” would raise both hands up when he was “covered,” something he did thousands of times for impressed fans. Then he would comply with a sea of autograph signing requests. A “Crash” Corrigan Fan Club of 220,000 youthful members was organized, complete with “Crash” Corrigan photo I.D. cards. In the 1950s, Tanner Gray Line Tours of Los Angeles scheduled motor coach tours of Corriganville. Their five-hour Wild West Movies Tour at $5.75 included a chuck wagon lunch. Benevolent societies, fraternal and social organizations rented Corriganville for group gatherings.36

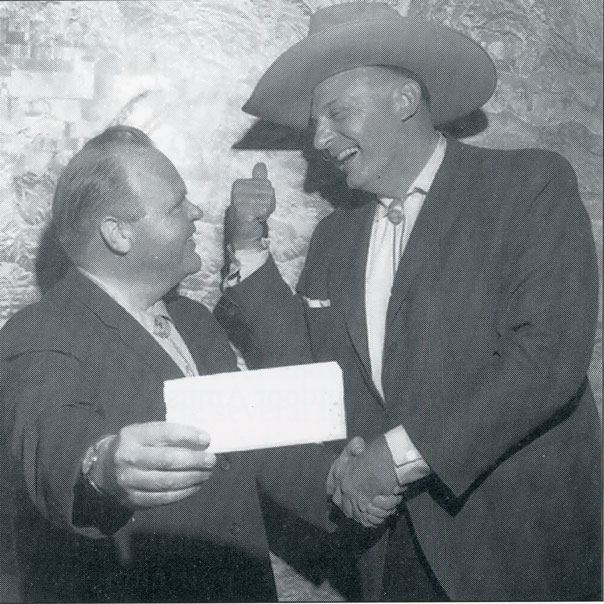

Corrigan’s successes attracted investors. In early 1955, Ray contracted a long-term lease with Outdoor Amusements, Inc. to manage operations at the ranch. Ray was to receive a $3,000-a-month rental fee and serve as an advisor and technical consultant. He retained ownership and control of his other enterprises, which included a gunite swimming pool construction company, his Sultana soft drink company (which made an Orange Julius-like beverage), and his real estate investments. Under the new management, facilities at Corriganville were expanded, new attractions were added to Silvertown, and additional movie sets and production equipment were provided.37

On August 3, 1954, the Jack Wrather Corporation of Dallas, Texas purchased all rights to “The Lone Ranger” television series from the George Trendle interests for $3 million. Wrather immediately upgraded this popular black and white series with color programming, and included location travel to ten scenic areas in California and Utah. Thirty-nine new programs in the series were produced for the 1956-57 television season. The series location headquarters was established at Corriganville. Wrather, whose investments were in radio, television and hotel enterprises, gained temporary control of Outdoor Amusements, Inc. As majority stockholder, he leveraged a name change for the Corriganville Movie Ranch from January 1957 until May 3, 1958, calling it the Lone Ranger Ranch. The only time Clayton Moore ever showed a hint of fear in his role as the Lone Ranger was at Corriganville, where several thousand kids charged at him during a rare public appearance on the Silvertown Main Street.

During this period, General Mills, Inc., sponsor of the radio and now television series, printed color cut-out images of Western town buildings on their Wheaties and Cheerios cereal boxes advertising the Lone Ranger Movie Ranch Wild West Town. Children could also send for a four-piece color map that was a flat landscape for the cardboard town buildings.38

Wrather’s control of Corriganville was terminated through a lawsuit by the Corrigans, who showed that Wrather was violating his contract by not keeping up physical appearances at the ranch and allowing the aged oak trees to die out. Some fire and flood damage was sustained at Corriganville in 1957. By summer 1958, the ranch was retitled “Corriganville: World’s Most Famous Movie Ranch.” Ray celebrated by opening Corriganville to the public all week long. Other promotional phrases over the years described it as a “nationally renowned movie and TV location site,” “The Old West,” “only location for the public to see movies being made,” “one of America’s top ten most interesting places,” and declared “over 3,500 pictures filmed at Corriganville.” In May 1962, Ray encouraged on-site camping at Corriganville, be it tent, camper or trailer.39

In the early 1960s, Corrigan’s expertise facilitated the founding of a movie industry workshop on the ranch. Called the Corriganville Academy of Motion Picture and Theatre Arts, it was more than a stunt school. It provided a training ground for potential actors in all phases of thespian techniques. The school offered live productions and workshops in stage management, and in equipment and set handling. The ten-week course covered “method” acting, character building, body movement, voice, diction, and constant participation in scenes, plays, set management and stunt routines. Placement help and a screen test film were also provided. After Corriganville closed, the dispersed stunt men/actors went on to do shows at Knott’s Berry Farm, and to create the stunt show program at Universal Studios. Corporate managers who worked for Ray took the skills learned at Corriganville and applied them to leadership positions at Disneyland and Universal Studios. (Previously, Universal had wanted to buy Corriganville as an appendage studio and tourist attraction.)40

Corriganville was a financial success throughout Ray’s twenty-nine year administration. Even the sensational front-page news coverage preceding Rita Jane and Ray’s divorce trial in 1954 failed to affect the earnings stability of the ranch. Ray had been eyeing his co-performer at the ranch, Elaine DuPont, while his foreman, Moses (“Bud”) Stiltz, was giving Ray’s wife Rita ardent personal attention. Eventually both parties legally obtained the objects of their desire. After the trial, Rita was awarded a continuing half-interest in the property, and she received an equal share of the net profits. (Ray’s rental fee from Outdoor Amusements was his alone.)

By April 1959, Ray had considered an additional $5 million expansion of Corriganville facilities, but when the State of California indicated its intention to route its 118 Freeway along the upper ranch property, such plans were set aside forever.41 The results would spoil numerous camera angles for the studios. The same fate befell the Iverson Ranch, which was breached fairly in the middle by the freeway. Further, Ray had also had a warning heart attack.

Other pressing reasons were associated with the costly overhead expenses of running a large ranch, including the payroll for a stable-full of cowboy stunt men, and the ongoing repairs. Ray and Elaine had to pay all of their debts from gate receipts, whereas other corporate theme parks had separate investments that served to defray their expenses.

Personal and regional problems aside, times were changing. Now, in the cynical sixties, cowboy heroes were vacating center stage to civil rights, flower children, hippies, Peter, Paul and Mary, and the Beatles. Cowboy actors were digesting spaghetti canned in Italy or Spain, instead of rare beef steaks. (The new diet made them mean and ornery and readily willing to wear nondescript brown clothing.) As a result, interest in traditional Western entertainment flagged by the early sixties. Corrigan made non-traditional attempts to recapture the public’s interest. He constructed a moto-cross motorcycle dirt track endurance course in a clearing above the lake, with trails that extended down toward the rodeo arena. This attempt brought crowds for a couple of years. Attendance at the rodeo dropped off, so Ray reworked the arena into a go-cart track, but the Simi Valley city council refused to issue an operating permit for the revised usage.42 When the ranch was sold for $2,800,000 to Bob Hope in 1965, Rita and Ray each pocketed a half-interest.43 The preeminent reason Ray had for selling the ranch was Rita’s desire to receive that check.

HOPETOWN

Bob Hope’s managers kept the movie ranch open to the public until 1967. The property name change to “Hopetown” was ill planned. It did not carry the same public recognition factor as the title “Corriganville.” The movie ranch remained accessible to the studios for commercials and movies, but on September 25 and 26, 1970, a major firestorm swept down from the Saugus-Newhall area, burning structures on the Iverson and Spahn movie ranches, then flaring over the pass to consume the large sets and most of the Silvertown buildings at Hopetown/Corriganville before moving on to Moorpark. Hope hung out a “closed” sign, locked the gates and walked away to wait out appreciating real estate values.44 He had acquired the ranch from Corrigan intending to carry on its Hollywood traditions, knowing that other movie ranches in Southern California had been sold, subdivided and forgotten. Hope did not want the same fate to befall Corriganville, which became, in essence, suspended in time, waiting for the desires of others to shape its future.

There was only one movie ranch like Corriganville as far as the public was concerned. Universal Studios would later conduct glitzy high-tech tours. “Old Tucson,” Arizona’s commercial movie ranch, would have its Spaghetti Western-like sepia-toned desert wasteland environment, but Corriganville fits comfortably in the well-worn pocket of memories that contain other treasures like the Saturday matinee, old radio programs and the original Ghost Town at Knott’s Berry Farm.

THE CORRIGANS AFTER CORRIGANVILLE

After their marriage on April 7, 1956, Elaine and Ray Corrigan had taken up residence in Northridge. The old Silvertown ranch house became headquarters for the ranch foreman. Elaine was cowgirl to “Crash” Corrigan’s cowboy role. Whenever Ray was called out to be Grand Marshal of a Southern California community parade, which he frequently was, he had a built-in queen to ride with him. After the sale of Corriganville, Ray and Elaine built a new 8,000 square foot home in Encino. Elaine, as “keeper of the dust” at Corriganville, managed to add a full-time career in professional banking, eventually becoming an institutional vice-president.45

Ray and Elaine had one daughter, Colleen Suzanne, born in 1961. Elaine had many well-placed friends and associates in both the financial and entertainment worlds. The gap between Ray and Elaine’s birthdays amounted to twenty-six years. In 1967, Elaine weighed the factors, including her husband’s sometimes mercurial personality, and asked Ray for a “friendly” divorce. Divorced on a Tuesday, they rode together with their daughter Colleen the following day in the 1967 Hollywood Santa Claus Lane Parade. Elaine later married Robert Calhoun and they had one daughter, Heather, born in 1973. Ray never remarried.46

Ray and Elaine sold the Encino house and Ray moved to Washington State in 1971. Here he considered developing a new public theme park in the San Juan Islands, the American soil closest to Vancouver Island and Victoria, British Colombia. He chose a high-traffic tourist location, but backed out due to its cost and prolonged development projection.

Ray then moved to Brookings, Oregon, just north of the California line, to a life of semi-retirement. He sold recreational vehicles, mobile homes, went fishing and jaunted off to Western film conventions where he was graciously greeted by admiring fans. An Oregon woman named Irene had made up her mind to become the next Mrs. Corrigan, but Ray permitted no legal ties. In May 1976, Ray was honored as Grand Marshal in Brookings’ Azalea Festival parade. But Corrigan, a constantly active man, was getting bored. He thought of moving back to Los Angeles to make personal appearances, go on talk shows, and considered doing character roles in Hollywood.

Corrigan came down to Los Angeles to participate in the one-time, four-day Western Film Festival held at the Biltmore Hotel on June 16-19, 1976. While in town, he had a chance to visit his daughter Pat in Canoga Park and to see his newborn granddaughter, Tricia, for the first time. Ray also visited his son Tom in Thousand Oaks. They talked about family, old times, the legacy of the ranch and about future plans, including Ray’s idea about returning to Los Angeles. They visited the ranch site together. Ray was depressed by its run-down appearance.

Back home again in Brookings, Ray got a call from the area Cadillac dealer. The new sedan he ordered had arrived. Would he come down and take delivery? Ray walked out the door and onto the lawn and collapsed with a fatal heart attack. It was August 10, 1976. Open-heart surgery was not a common practice then. Ray had avoided doctors. He was a self-treating naturopath in concept and practice, perhaps as an outgrowth of his training under Bernarr Macfadden.47

Because of his association with Hollywood, Ray Corrigan had a remarkable and complex career spanning four decades. He was in the public eye for twenty-two years after his last appearance in a regular movie series, and he retained his popularity throughout. The management of his movie ranch and other enterprises kept him visible and available, while other western movie heroes often just rode off into the sunset.

AFTER RAY CORRIGAN

With the blossoming of Simi Valley as a bedroom community in the 1960s, Corriganville was largely forgotten. The 1970s were a time of emptiness and abandonment for the Hopetown property, except for an occasional moto-cross cycle race scheduled to keep a county permit alive. The 1970s had opened with a devastating fire that destroyed most of the ranch’s standing structures. The decade closed in a like manner. Halloween vandals set another fire in 1979 that eliminated the hotel/soundstage and related buildings, and leveled the combustible portion of the livery stable. Now only furtive wanderers tread the trails of the abandoned ranch, with the exception of an occasional Western movie fan trying to recover past glories. A firing range was constructed for the Simi Valley Police Department adjacent to the old Fort Apache site on the ranch. It was in use from late 1975 to August 1987.

The 1980s became years of administrative resurrection for the original Corriganville. Eyes began to turn toward the secluded Bob Hope property for various reasons. Residential crowding demanded more green space. Voices were raised on behalf of migratory animal corridors, the protection of rare plant habitats, leaving the property “as is,” and, of course, real estate development. These various voices all spoke out when the development firm of Griffin Homes purchased an option on the entire remaining ranch site in 1983 from Bob Hope for $4.6 million. Public hearings were held by the City of Simi Valley. Strong public support existed for the preservation of the main ranch areas as a public recreational park. The City stepped in and allowed Griffin Homes to purchase the ranch’s western-most sixty acres, to be used for a development comprised of single-family homes. Griffin’s remaining 172 acres of the ranch were purchased by the City for a regional park, with local and State resources provided by the City, the Rancho Simi Recreation and Park District, and the Santa Monica Mountains Conservancy. Eventually, 225 acres of the area once known as Corriganville were secured.48

Once the deed to the property was obtained in April 1988, the City of Simi Valley organized the Rancho Simi Open Space Conservation Agency (RSOSCA) board to govern the affairs of the newly acquired regional park. By December 1988, RSOSCA’s Master Plan was published, containing the best conservative development ideas the community had rallied around in the previous few years. Phase I of the plan was structured to install the basic physical fixtures and accommodations of a public park, including a visitor’s center. Phase II addressed reconstruction of the major features of the historic movie ranch: the Silvertown street, the lake, a Fort Apache structure, trimming of Robin Hood Forest, greening of the meadows, and restoration of the trails. The name “Corriganville Park” was also legally restored to the ranch.49

Since 1985, various Simi Valley citizens’ groups have been organized to promote Corriganville as a historic reminder of Hollywood’s earlier movie making days, and to recall the public’s enjoyable visits to the ranch. The first of these groups to appear was the Simi Valley Cultural Association, then came the Corriganville Preservation Committee, followed by the Corriganville Movie Ranch Restoration organization. These dedicated groups tried to raise monies at the local level to allow for the reconstruction of structures addressed in Phase II. Another local group interested in promoting old Corriganville’s welfare is the Trail Riders of the West, whose members are saving Hollywood Western memorabilia for a museum at the Park’s visitors’ center.50

The 1990s have come and are nearly gone. Clean-up and restoration funding has proven too difficult to raise, either at the official City level with grant proposals or ballot propositions, or at the citizens’ support level, with event-oriented fund raising. The various construction projects in both Phases I and II of the Park’s Master Plan are still awaiting funding.

The memory of Corriganville is still strong, kept alive by those who visited the movie ranch during the eighteen years it was open to the public. Yesterday’s child visitors are today’s business people, corporate executives and other interested parties. This potential advocacy group could be encouraged to support Corriganville’s rebirth through, among other options, structured giving plans. Visits to the ranch by Hollywood production companies anxiously looking for new vistas and additional sound stages could do wonders for the ranch’s progress. As the fiftieth anniversary of Corriganville’s public debut dawns, $6.4 million in reconstruction funds still need to be raised. Focusing on avenues of support that can provide the largest return is a recommended resolution for the new century.

The grounds of Corriganville, with limited improvements in place, are now open to the public once more. Gone will be its former genial host, Ray “Crash” Corrigan, who often personally greeted his guests at the ranch entrance with “Howdy, Pardner.” The present owners will have to proceed without the expertise, showmanship and public affability of our movie cowboy hero. Former visitors returning to Corriganville today, though, can tell them all about it. They’ve been there before.

Make History!

Support The Museum of Ventura County!

Membership

Join the Museum and you, your family, and guests will enjoy all the special benefits that make being a member of the Museum of Ventura County so worthwhile.

Support

Your donation will help support our online initiatives, keep exhibitions open and evolving, protect collections, and support education programs.

- Tom Corrigan, interviewed by William Ehrheart, 24 April 1991, tape recording, Oral History Center, Library, California State University, Fullerton. Hereafter, Interview, Tom Corrigan. Editor’s note: Bernarr Macfadden launched his first magazine in 1899 with Physical Culture, and went on to create a publishing empire which included True Detective, True Story, True Romance, Movie Mirror and Liberty magazines. By 1935, his publications “had a combined circulation surpassing those of the other giants of magazine publishing, Hearst, Luce and Curtis.” Married four times (the last time at age 80), Macfadden died at the age of 87 in 1955. See Joseph F. Wilkinson, “Look at Me.” Smithsonian 28, no. 9 (December 1997): 136-151.

- Interview, Tom Corrigan.

- Ormond Powers, “Popular Western Star Got His Start As Physical Instructor for Actresses, Corrigan Gave Joan Crawford Her Shoulders,” Orlando (Fla.) Morning Sentinel, 19 February 1940. Interview, Tom Corrigan. DeWitt Bodeen, From Hollywood (South Brunswick, N.J.: A.F. Barnes Co., 1976), 279-295. James Robert Parish, The Hollywood Beauties (New Rochelle, N.Y. : Arlington Publishers, 1978), 12-62.

- Capt. F.J. Franklin, “Ray Corrigan to Develop at McScott Ranch,” Simi Enterprise, 30 September 1937, p. 1. Ray as an adult: 6 ft. 2 ½ in., 199 lbs., gray eyes, dark brown hair.

- Jungle movies declined after 1954, along with classic monster movies. These were replaced by outer space and alien-type films, reflecting a new level of scientific sophistication in the viewing public.

- “Tarzan Entertains,” Beverly Hills Town Topics, 21 February 1934. Interview, Tom Corrigan.

- Interview, Tom Corrigan. The Flying Codonas, circus trapeze artists, performed the vine swinging for MGM’s 1932 Tarzan of the Apes. They trained Ray for the 1934 MGM release, Tarzan and His Mate. Ray could stay underwater for 3 ½ minutes. See Wildest Westerns magazine, 6 (June 1961): 44, 45.

- Interview, Tom Corrigan.

- Corriganville Park Master Plan, Simi Valley, California (San Francisco: Wallace, Roberts & Todd, Park Planners for the Rancho Simi Open Space Conservation Agency [RSOSCA], 1988), 33. Editor’s note: Fourteen leagues were granted in 1795 and 1821 to 3 Picos: Francisco Javier, Miguel and Patricio. In 1802 it was held by Luis Pena and Santiago Pico, and in 1831 , Romualdo Pacheco was granted the use of a portion. Regranted in 1842 to Manuel and Patricio Pico. Jose de la Guerra y Noriega was claimant for 113,009 acres, patented on June 29, 1865. See Robert G. Cowan, Ranchos of California: A List of Spanish Concessions 1775-1822 and Mexican Grants 1822-1846 (Los Angeles: Historical Society of Southern California, 1977), 98.

- Ray B. Corrigan, “Last Living Frontier” (December 1961), 16mm. color/sound film documentary of the Corriganville Movie Ranch, Tom Corrigan Collection.

- Mrs. D.D. DeNure, “Tiburcio Vasquez,” in Legends and Lore of Long Ago of Ventura County (Los Angeles: Wetzel Publishing, Inc., 1929), 33-39. Charles F. Outland, Stagecoaching on El Camino Real: Los Angeles to San Francisco, 1861-1901 (Glendale: The Arthur H. Clark Co., 1973), 53.

- Outland, 45-48, 50.

- Franklin, p.1. “Leo Carrillo Accepts Repeat in History,” Simi Enterprise (no date), Corriganville ranch scrapbook, Tom Corrigan Collection. Leo Carrillo, The California I love (Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall, 1961), 164. “E.J.” Leo’s older brother, was previously City Engineer for Santa Monica, California. E.J. was later credited with the construction of ldlewild Airport and other structures in New York City.

- Ray had briefly been married earlier to a young woman he had met on one of his public tours, believing she was pregnant. When the stated pregnancy failed to manifest itself, Ray ended the marriage. Interview, Tom Corrigan.

- Interview, Tom Corrigan. Eddie Dean, interview by William Ehrheart, 19 August 1996, tape recording and transcript in possession of the author.

- An additional 110 acres of the ranch lay on the Los Angeles side of the county line.

- Maps of School Districts, Book C, Assessor’s Office, Ventura County, Misc., page 34, Simi; Jonathan R. Scott, 1829. 74 acres net in Ventura County. Nettie Brestrand, “Raoul Walsh: Man’s western director,” Thousand Oaks News Chronicle, Special Edition, 31 August 1980, “Ventura County…its celluloid cowboys,” Sec. A, p. A-15, col. 1.

- Franklin, p. 1.

- Interview, Tom Corrigan. Franklin, p. 1.

- Joe Paul, Jr., “County Motion Picture Location to be Dude Ranch Vacation Spot,” Ventura County Star-Free Press, 21 June 1949, p. 2. Interview, Tom Corrigan. Some of Corriganville’ “jungle” area included the overgrown meadows in the “Burma Road” sector below Rocky Peak.

- Interview, Tom Corrigan.

- Interview, Tom Corrigan.

- Patricia Daly, “Home was a site for Westerns,” “Neighbors,” Simi Daily News, 24 July 1985, p. 7. Interview, Tom Corrigan.

- William J. Ehrheart, “A Presentation to Establish a Thematic Designation Category for Classic Southern California Movie Ranches as State Registered Historical Landmarks,” 17 July 1996, Office of Historic Preservation, California Department of Parks and Recreation, Sacramento, Calif.

- Edwin Iverson, nephew of Joe Iverson the co-owner of Iverson’s Movie Ranch, telephone interview, 22 April 1994.

- Ehrheart, “A Presentation…. ” Interview, Tom Corrigan.

- Editor’s note: Presently, Knott’s Berry Farm, “the nation’s last major family owned amusement park” is tentatively in the process of being sold to a Sandusky, Ohio business partnership, Cedar Fair LP, for an estimated $300 million. Ranked third in U.S. theme park attendance in 1990, the Buena Park attraction’s share of the market has slipped from third to twelfth place nationally as competitors such as Disneyland, Universal Studios and Magic Mountain have grown faster and farther, extending into international markets. See James Granelli, “Ohio Firm to Buy Knott’s Berry Farm.” Los Angeles Times, October 22, 1997, pp. A 1, A23.

- Maxwell Barlow, Mayor of Ghost Town and historian at Knott’s Berry Farm, interview by William Ehrheart, 28 September 1994. Public Relations historical information packet, Knott’s Berry Farm , 1994.

- Joe Paul, Jr., “Dude Ranch with Movie Glamour is Taking Form Here,” Simi Enterprise, 31 March 1949. “Purchase Gives Corriganville Frontage on Los Angeles Ave.,” Simi Enterprise, 3 May 1953. The volume of public business generated by the ranch led the U.S. Post Office Department to locate a rural postal station at Corriganville, from June 16, 1959 until November 19, 1965, with Ray Corrigan installed as manager.

- Ray Corrigan followed other cowboy movie heroes with circus experience, a phenomenon of the Depression ’30s: Tom Mix, Col. Tim McCoy, Ken Maynard, Buck Jones and Hoot Gibson. Ray learned much of his cowboy stunting and horse handling from eminent stunt man/actor Yakima Canutt.

- Corriganville advertisements in Ray Corrigan’s scrapbooks, Tom Corrigan Collection. Photograph of Los Angeles Avenue entrance gates, ranch archives, Tom Corrigan Collection.

- Elaine (Corrigan) Calhoun, interview by William Ehrheart, 6 October 1994, tape recording and transcript collection of the author. Hereafter, Interview, Elaine Calhoun.

- “…over 25,000 rounds of ammunition are fired each year at the Lone Ranger Ranch (Corriganville).” Van Nuys News, 14 March 1957.

- Corriganville Gazette, Special Edition, vol. 1, no. 2.

- Advertisements, ranch scrapbooks. Ray installed a scaled-down Old West train in the early 1960s that was identical to one now available at the Old Tucson Movie Ranch in Arizona. Knott’s Berry Farm had a full-sized narrow gauge train, but with a track nearly half as long as the route at Corriganville.

- Advertisements, Corriganville scrapbooks. Tom Corrigan Collection. Interview, Tom Corrigan.

- “New Units Built at Corriganville,” Simi Enterprise, 7 April 1955. Ray’s pool construction logo was a silver dollar embedded in the side of the pool. Elaine DuPont, a reigning beauty queen many times over, was also “Miss Sultana.” Interview, Tom Corrigan.

- David Rothel, Who Was That Masked Man: The Story of the Lone Ranger (Cranbury, N.J.: A.S. Barnes & Co., 1976), 200-201 , 219, 238.

- Ray Corrigan declared that the 3,500-film total consisted of approximately 700 movie films and 2,800 television episodes. Interview, Tom Corrigan. Advertisements, Corriganville ranch scrapbooks, Tom Corrigan Collection.

- Corriganville Gazette, Special Edition, vol. 1, no. 2. Interview, Tom Corrigan.

- Interview, Elaine (Corrigan) Calhoun. Interview, Tom Corrigan. “Corriganville Plans $5 Million Expansion” Ventura Star Free Press, 13 April 1959. “Express Highway Planned Through Simi Valley, Local Interest Growing,” Oxnard Press Courier, 15 August 1959.

- Interview, Tom Corrigan.

- Interview, Tom Corrigan. “ ‘Crash’ Corrigan Going Fishing: Pockets $1 Million Check,” The Ventura County Star-Free Press, 3 April 1965, p. A5.

- Interview, Tom Corrigan. Maida Ewing, “Simi Valley survives ring of fire: Homes periled, many evacuated”; Maxine Reese, “Nothing we can do”; Bob Martin, “Pre-fire winds also hurt city,” Simi Valley and Moorpark Enterprise Sun and News, 27 September 1970, p. 1. Maida Ewing, “Simi’s share in fire damages; $550,000 fire loss,” Simi Valley Enterprise Sun and News , 9 October 1970, p. 1.

- Interview, Elaine (Corrigan) Calhoun. Today she also heads a Hollywood film production company.

- Interview, Elaine (Corrigan) Calhoun.

- Interview, Tom Corrigan. Ray once sustained a broken nose while filming a television episode of the “Danger Is My Business” series, shot at Corriganville. Ray had just completed a hazardous cliff-fall onto an oversized trampoline with satisfactory results. Stepping off the trampoline onto the ground, Ray tripped and broke his nose. Ray compensated for the accident by shoving two wooden pencils up his nostrils and taping them in place. “Crash” Corrigan is buried at Inglewood Park Cemetery in Inglewood, California. Editor’s note: Bernarr Macfadden, who eschewed any conventional health care with the exception of dentistry, eventually died of “jaundice aggravated by fasting.” See Joseph F. Wilkinson, “Look at Me.” Smithsonian 28, no. 9 (December 1997): 151.

- Corriganville Park Master Plan, p. 3. Elizabeth Campos, “Hopetown Added to State Bill,” Simi Valley Enterprise, 4 September 1987, p. 1.

- Elizabeth Campos Rais, “Public Gets Deed to Hopetown,” Simi Valley Enterprise, 5 April 1988, pp. 1, 7. The Agency Board is composed of two city council members, two members of the Rancho Simi Recreation and Park District, and one public member. Corriganville Park Master Plan Report (December 1988), as quoted in “Corriganville Benefit Program,” Corriganville Preservation Committee, p. 3. Nettie Bredstrand, “Original Name Asked for Ranch,” Thousand Oaks News Chronicle, 7 April 1988.

- Corriganville Preservation Committee Newsletter, Special Edition, vol. 4, no. 1, p. 2. Corriganville Movie Ranch Restoration bulletin.