By Powell Greenland

In this month’s Journal Flashback we are sharing an article on the original Port Hueneme Lighthouse. The precariousness of the Santa Barbara Channel necessitated a lighthouse at the channel’s entrance. The author details the history of the lighthouse, the uniforms and lifestyle of lighthouse keepers, and various shipwrecks prior to the construction of the lighthouse. While the original structure sadly no longer exists, the current lighthouse is open to tours on certain days of the month. Check the city of Port Hueneme’s website for open hours. For those who are interested you can request copies of the original quarterly, which includes profiles on lighthouse keepers over the years, from the Research Library. This article is from Volume 52, Number 2 (2010). Enjoy!

The early history of Ventura County, and particularly Port Hueneme, was indelibly influenced by the arrival of Thomas R. Bard in 1865. A gangling young man of twenty-three, Bard cultivated a sweeping mustache to disguise his youth, but had matured well beyond his years during the havoc of the Civil War. An invading Confederate army had torched his hometown of Chambersburg, Pennsylvania, including his mother’s house, and as an employee of the Cumberland Valley Railway he had distinguished himself during a harrowing experience behind enemy lines during the Battle of Antietam in 1862. Fresh from his encounter with war, Bard was made an agent for his employer, the oil and railroad magnate and Assistant Secretary of War Thomas A. Scott. Bard was charged with the responsibility of buying land and drilling for oil in unproven terrain. From this new role he would become a pioneer oil and land developer, rancher, entrepreneur, the founding president of Union Oil Company and eventually a United States senator.

Bard arrived in Santa Barbara aboard the side-wheel steamer Senator in January 1865, and soon began drilling at a site in the upper Ojai, bringing in the first freeflowing oil well in the state of California. As Scott’s land agent, Bard took control of all of Scott’s Southern California holdings, including the 32,100-acre Rancho Rio de Santa Clara o La Colonia, purchased the year before his arrival. This vast acreage encompassed most of what would later become Oxnard and all of Port Hueneme, and would eventually become the location of the Bard family home.1

As early as 1867, Bard envisioned a wharf at Point Hueneme to serve the farmlands and growing communities in the area. On a two-day exploration of the coastline with friend Captain W.E. Greenwell of the U.S. Geodetic Survey, Bard learned of a submarine canyon just east of Point Hueneme. At this location, the sea floor dropped from six fathoms (11 meters) near the shoreline, to ninety fathoms within a few hundred yards, and then suddenly, as though arriving at a sheer precipice, it dropped to the amazing depth of two hundred fathoms (365 meters). To Captain Greenwell’s experienced eye, this was an ideal location for the construction of a wharf.2

A land dispute, however, intervened. About one hundred squatters had already appropriated the land at the site of the proposed wharf and had even formed a small village they called “Wynema,” an adaptation of “Hueneme,” the Spanish transcription of the original Chumash name for the area, meaning “resting place.” They contended that the survey of the land grant was incorrect and accordingly, they had settled on what they claimed to be free, open land. With no option other than a prolonged legal contest available, Bard and a determined group of armed supporters headed toward the occupied site, precipitating what would become known as the “Hueneme War.” Fortunately no shots were fired, and eventually an equitable agreement with the squatters allowed Bard to build his wharf while awaiting a ruling from the Secretary of the Interior, a decision which years later favored his position.3

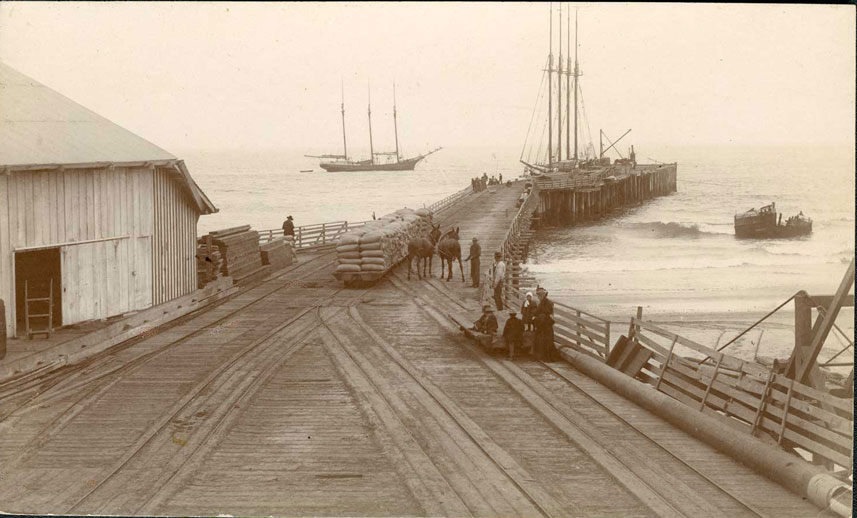

The site chosen for the new wharf, together with Anacapa Island nearly eleven miles due south, formed the eastern entrance to the Santa Barbara Channel. The Point was long, rounding, low and sandy, and was the most projecting point in the sweep of the lowlands of the Santa Clara Valley. Construction of the wharf began May 23, 1871. A drilling rig formerly used by Bard in his oil operations was brought to the site to dig an artesian well, whose purpose was to supply water for ships as well as the teams bringing shipments to the wharf.

Originally 900 feet long, the wharf boasted a width of forty feet at the loading face. A rail track was laid the entire length, initially accommodating a train of twenty-four cars, each capable of carrying one hundred sacks of grain. Three large warehouses were also constructed on the shore nearby. Over the years, the wharf would be lengthened, ultimately extending 1,700 feet into the sea. The marsh to the east of the wharf, known as the Hueneme Slough, would later be filled in by the materials dredged for the future harbor. The one hundred-acre salt marsh west of the wharf was the site of the harbor itself.

Thomas Bard platted the nearby town in June 1872, borrowing a device from his hometown of Chambersburg by forming a diamond of the central streets. He named many of the streets after friends, relatives or boyhood memories. For example, Scott Street was named after his employer and Clara Street for his future sister-in-law. With the establishment of a new post office, Bard officially changed the spelling of the town’s name from “Wynema” back to its Spanish form, “Hueneme.” Within the next few years, the little town of Hueneme could claim that it was the greatest grain port on the southern coast and the eastern gateway to the Santa Barbara Channel. From Point Hueneme to Point Conception the mainland coast forms the northern shore of the Santa Barbara Channel, which is about sixtysix miles in length in an east-west direction. The four islands forming the southern boundary begin in the east with the narrow, five-mile-long Anacapa Island, which is actually composed of three separate islets. Next in the chain is the largest, Santa Cruz, with a rugged 62,000 acres, followed by the next largest, the 55,000-acre Santa Rosa Island. The chain ends with the westernmost island San Miguel, opposite Point Conception, forming the channel’s western entrance. The eastern entrance to the channel, flanked by Point Hueneme and Anacapa Island, is eleven miles wide, increasing gradually in width to the westward end that is twenty-three miles wide.

Prior to the mid-nineteenth century, sailing ships bound for points north often avoided using the Santa Barbara Channel, but as the age of steam took hold of the Pacific shipping trade and coastal populations increased, the channel grew in importance. As early as 1849, Pacific steamships travelling to and from San Francisco regularly used the channel, since they could shave ten to twelve hours each way off their journeys up and down the coast. The town of Santa Barbara, because of its size and relative importance, became a somewhat regular stop for the steamers. As a result of the increasing traffic in the Santa Barbara Channel, the United States Lighthouse Board established light stations at both Santa Barbara and Point Conception by 1856, just three years after the first California lighthouse was erected on Alcatraz Island in the San Francisco Bay.

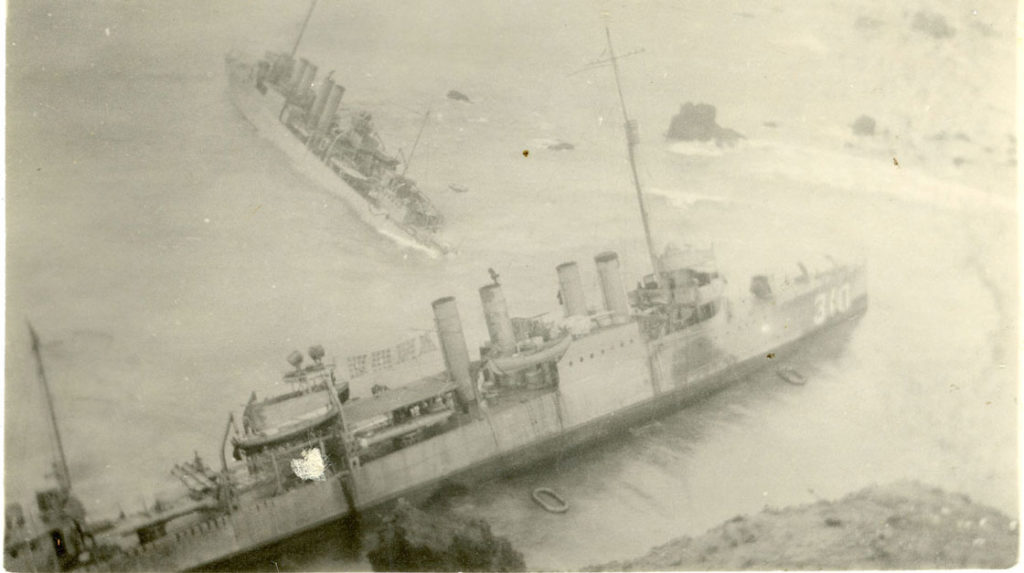

During the 1850s and ‘60s, the breakup of the great land-grant ranches in California, many of which were sold and divided into farms and small communities, attracted waves of migrants into the area. This influx led to an unparalleled growth in shipping on the entire Pacific Coast from San Diego to Washington to keep up with the insatiable demands of the new settlements, particularly for lumber. Beginning at Hueneme, during the 1870s no fewer than six wharves were constructed on the coast of the Santa Barbara Channel, including those at San Buenaventura, Carpinteria, Santa Barbara, Goleta, and Gaviota. The Santa Barbara Channel soon became a very busy place. It also was a very dangerous place. The six nautical miles of ocean surrounding the Channel Islands alone contain more than 140 shipwrecks, dating from 1853 to 1980, making the area not only a favored site for marine archeologists, but also a grim reminder of its navigational hazards.4

The first shipwreck in the Santa Barbara Channel occurred in early December 1853 off Anacapa Island, just twelve miles from Point Hueneme. In July of that year, the Pacific Mail Steamship Company of San Francisco had purchased the Winfield Scott and put the ship on the Panama run. On December 2, Captain Simon Blunt, with at least 200 passengers aboard (some accounts put the number as high as 400) set his course after rounding Point Conception directly for the Santa Barbara Channel. The Captain intended to save twelve to twenty hours, attempting a record run on the ship’s passage to Panama. It appears the top speed for this ship was about ten to twelve knots, roughly twelve miles per hour. Shortly after entering the channel, the vessel encountered “fog so dense you could cut it with a knife,” and had to make a sudden alteration of course to avoid a treacherous barrier of rocks off Santa Cruz Island.

Late that night, the ill-fated vessel’s luck ran out and in the blackness of that terrifying moment it crashed its bow onto an unseen rocky shoal. The captain immediately reversed the engines but struck the stern on a rock and lost the ship’s rudder. He then wisely ordered the ship full speed ahead, lodging it precariously on a ledge of rocks before ordering all fires extinguished in the engine room. Although the Winfield Scott was eventually lost, all passengers, clad in life jackets were safely put ashore in lifeboats on a barren rocky shelf 200 yards off Anacapa Island. It was later determined the wreck occurred near the rocky gap that separates Middle Anacapa from the eastern island. The ship’s bow was lodged high on a ledge with the stern completely submerged. The wreck occurred in twenty-two fathoms of water.

At first light on December 3, boats were again launched, taking all passengers from the ledge to an easily accessible location on the island, today known as Frenchy’s Cove. In addition, food, blankets and $2 million in gold bullion were removed from the ship. The following morning the steamer California, bound for San Francisco with Captain Leroy in command, sighted the stranded passengers. Although space was limited, the rescue vessel took all the women, children and the infirm aboard ship on its passage to San Francisco. The rest of the passengers awaited the arrival some days later of the returning California, now wellprovisioned on its scheduled run from San Francisco to Panama. All of the ship’s company remained on the island for an additional two days, busy recovering the rest of the salvageable baggage and mail. The wreck was abandoned on December 12, 1853.5

In an official report of the Lighthouse Board, dated September 25, 1871, the following recommendations were listed:

Anacapa lsland, west side of southern entrance to the Santa Barbara Channel, California.-An appropriation of $70,000 is recommended for the establishment of a first-order Light-station at the eastern end of this island. The island is a barren rock about one hundred and fifty feet above the sea, destitute of verdure, and all the water and other materials necessary to prosecute the work will have to be brought from the mainland. A Fog signal is not recommended on the island, as the coast steamers usually pass nearer the mainland.

Point Hueneme, sea coast of California, east side of southern entrance to Santa Barbara Channel. An appropriation of $10,000 is recommended for the erection of a first-class steam Fog signal at this point, which is directly opposite Anacapa Island. With a firstorder Light on the eastern end of Anacapa Island, and a steam Fog signal on the western extremity Point Hueneme, the southern approaches to Santa Barbara Channel will be well marked and the navigation of the waters of that portion of California coast rendered less dangerous.

Despite these dangers, the government took no action on either of these recommendations by the Lighthouse Board. But with the construction of the wharf at Hueneme, the increased ship traffic in the area magnified the navigational hazards and made a lighthouse mandatory. By mid-1874, with a $22,000 appropriation from Congress, the Lighthouse Board finally approved the construction of a facility at Point Hueneme rather than Anacapa Island. The stately structure was built by the Salisbury Company. Thomas Bard had formed the firm to construct his wharf with A.J. Salisbury, Bard’s drilling foreman during his early days on the Rancho Ojai and a man he described as a “mechanical genius.” The architectural plans were drawn by the noted architect Paul Pelz, chief draftsman for the Lighthouse Board, whose firm would later win the design competition for the new Library of Congress building in Washington, D.C. During construction, a red whistling buoy was placed in thirteen fathoms of water two miles true south of the lighthouse site in order to guide vessels into port.

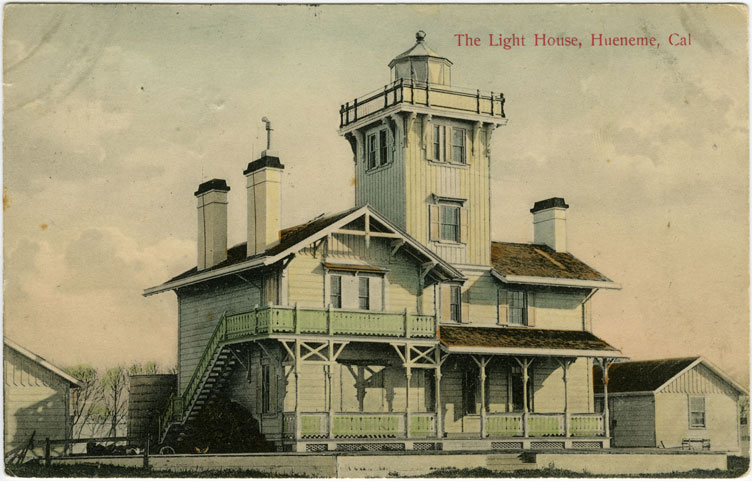

The design for the lighthouse at Hueneme was very similar to five others designed by Pelz, all constructed between 1872 and 1875. The first lighthouse was the Mare Island Station at San Pablo Bay, California; followed by Hereford Inlet Light Station, Anglesea, New Jersey; East Brother Light Station, San Francisco Bay; Point Fermin Light Station, San Pedro, California; Point Hueneme Light Station and, finally, the Point Adams Light Station at Hammond, Oregon. All of these lighthouses, because of similarity of design, became known as the “Sisters.” But the Point Fermin and Point Hueneme lighthouses were the only two exact twin sisters, built simultaneously and their lights were activated at the same time on December 15, 1874.6

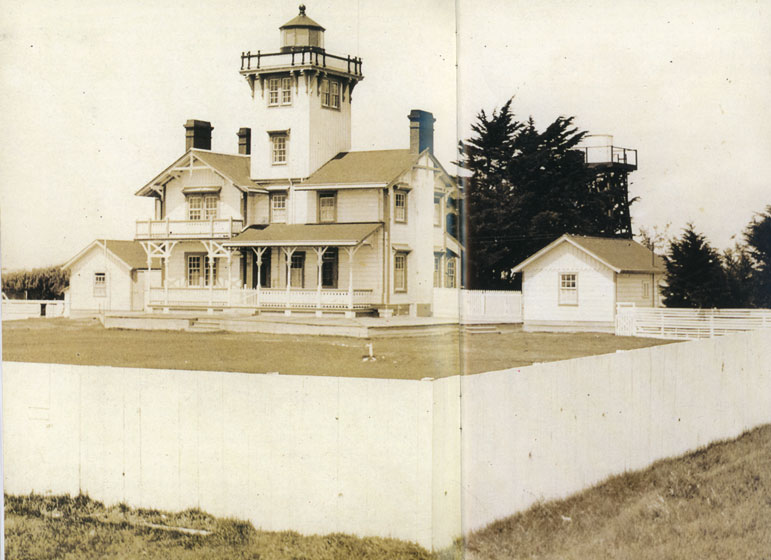

The architectural style Pelz employed for the “Sisters” has been termed “Swiss Carpenter Gothic” or, more often, “Victorian Stick.” It is characterized by gabled roofs with decorative trusses in the apex, hand carved porch railings, decorative cross beams and early Victorian horizontal and wooden wall sheathing. It should be noted that the visible wood members of the Stick style were purely ornamental with no structural function. In terms of lighthouse construction, the Pelz design was a radical departure from the past because it combined the light tower with the keeper’s dwelling, maintaining its architectural integrity with a stately elegance. All of the “Sisters” were initially painted a light buff, but some, like those at Point Hueneme and Point Fermin were changed to pure white.

Pelz’s original design for the Hueneme Lighthouse can still be seen in its twin “sister,” the Point Fermin Lighthouse. The Point Fermin light was blacked out following the bombing of Pearl Harbor and was never lit again. The Los Angeles Harbor Light, constructed on the breakwater in 1913, had put an end to its usefulness. Two more of Pelz’s lighthouses can still be viewed as well. Following the deactivation of New Jersey’s Hereford Inlet Lighthouse in 1964, there was a movement in the community to save this beautiful, historic building for posterity. As a result, this picturesque landmark was moved to North Wildwood, New Jersey, where the public can view it today. The East Brother Lighthouse, perched atop its tiny island in San Francisco Bay, after being fully restored to its former elegance was converted into a very popular bed and breakfast inn. In 1980, a group of preservationists got permission from the Coast Guard, which owns the island, to renovate the lighthouse and take over its maintenance. Oakland engineer Walter Fanning, whose grandparents had been lighthouse keepers on East Brother decades before, led the group. The other three sisters, including the one at Point Hueneme, have been demolished. The Mare Island Lighthouse, perched high on a hill with a supply pier far below, outlived its usefulness in 1910 when it was replaced by the Carquinez light. It was abandoned in 1917 and razed in the 1930s. The Point Adams Lighthouse, located on the Oregon side of the Columbia River, was deactivated in 1899, destroyed in 1912, and replaced by the Desdemona Lighthouse.7

The original Point Hueneme Lighthouse was a well-built, two-story, oak frame structure resting on a brick foundation that rose to about four feet above ground level. It had ten rooms, four fireplaces, and a three-story, sixty-five-foot light tower. The first floor of the building served as quarters for the keeper and his family, while the second floor was reserved for the assistant keeper and family. The second floor was identical to the ground floor and could be reached by either an interior or exterior set of stairs. From the second floor the tower was ascended by a steep, winding stairway that led to the third floor, a square, unadorned room relieved by one window that faced the sea. This room was known as the “oil room” because the barrels of fuel oil for the lantern were stored there. It was also occasionally referred to as the “work room” because cleaning supplies were stored in a small chest of four drawers, set against the wall. The next floor, although similar in size to the room below, was brightened by three identical large windows. One faced the ocean and the other two took up most of the space on the two side walls, all offering magnificent views. This floor was known as the “watch room” because it was here that the keeper spent much of his time during his watch.

The climb from the watch room to the lantern room was short but very steep. This room was actually situated above the wooden tower and was completely enclosed by glass storm panes in brass frames and covered by a copper-clad dome. An adjustable ball vent surmounted the dome and allowed air to enter the room. Rising from the ball was a lightning rod, an ever-present feature on all lighthouses. Outside the glass-enclosed wall and accessible by a door, was a circular walkway with an ornate waist-high protective enclosure known as a gallery. It served as a safe place for window cleaning, painting, and repair work. The centerpiece of the lantern room, of course, was the lens and the lamp.

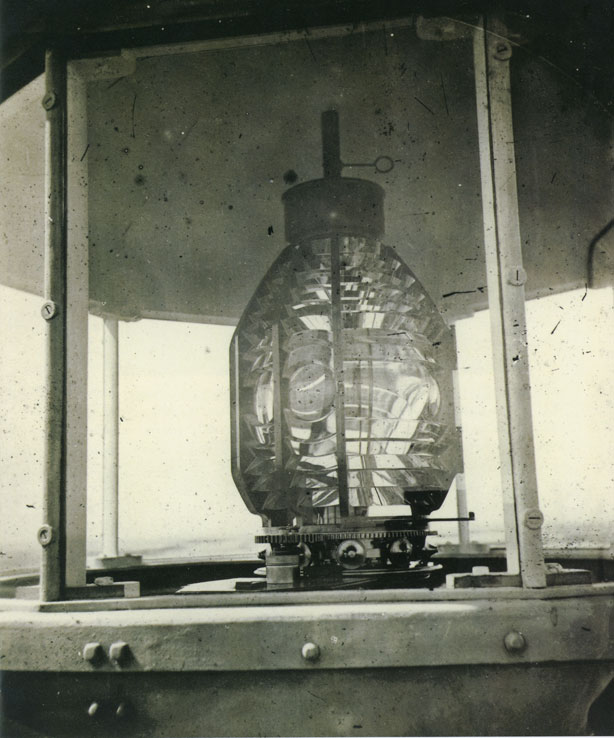

The Hueneme light flashed white from 1874 until 1889, at which time the signal was changed to fixed red. In 1892 it was changed again to an oscillating white signal set to shine a fixed white for one minute followed by six consecutive flashes of ten seconds each. The illuminating apparatus, about three feet in length by two feet in diameter and sitting on a vented pedestal, could light thirty-six degrees of the horizon. It was made to revolve by a hand-wound clock-work arrangement driven by weights and gears; the former attached to a hemp rope that extended through holes in the floor of the lantern room and similar holes in the floor of the watch room down to the oil room. The mechanism has been likened to the works of an old-fashioned grandfather clock. Every evening, the keeper on duty was required to wind the clock weight and clean the clockworks and oil them if needed. He would also check the wind direction in the lantern room and properly adjust the vents.

In 1874 the lamp was described as a Funk float, lard-oil lamp. It was later changed, however, under Lighthouse Board regulations, to a fourth-order Funk’s Mineral Float that burned kerosene. At that time the oil room was no longer used to store fuel as the kerosene had to be kept outside in a sheltered room. The light was rated to be seen in clear weather at fifteen feet above sea level for twelve and three-fourths nautical miles; at thirty feet it was visible for an additional two nautical miles. In 1925 the light at the Point Hueneme Lighthouse was electrified, replacing the kerosene lamp in the lens with a solitary 1000-watt bulb with an intensity of 200,000 candlepower.8

An abundant supply of water was delivered from an artesian well that had enough pressure to carry water four feet above the second floor. However, by 1882, the well was invaded by saltwater and the system had to be replaced with a 10,000-gallon tank to catch rainwater from the roofs. The entire lighthouse reservation covered thirty acres, part of it consisting of wetlands. The principle crop raised at the station was alfalfa. The lighthouse itself and surrounding grounds accounted for about fourteen acres.

In 1882 the Lighthouse Board made a request to Congress for a steam fog signal to be installed at Point Hueneme. It was noted that the numerous passenger and cargo steamers going up and down the coast passed inside Anacapa Island and very near the coast, which at that point made a considerable elbow. In addition, the land was quite low, giving very poor visibility in any fog. Their request for $7,000 was quickly approved, and the installation of the fog signal soon followed.

The Pacific Coast Pilot, a navigational guidebook published in 1889, has left this excellent description of the lighthouse from a seaman’s perspective:

The buildings are erected on a slight elevation, only eight to ten feet above the sea-level, very near the extremity of the low sand point [Point Hueneme], with marshes behind it. The tower rises from the wooden house, which is painted a light buff, and from seaward shows very well when projected on the hazy background of the distant hills. The lighthouse first exhibited in 1874, and shows from sunset to sunrise. It is a sea-coast light of the fourth-order of the system of Fresnel, and shows a fixed red light. It illuminates the entire horizon, and the focal plane is elevated fifty-four feet above the mean level of the sea.9

The Fresnel (pronounced “fren-el”) lens, referred to above, was actually installed at the Point Hueneme Lighthouse in 1897, and it improved the light’s visibility. The lens was invented in 1822 by French physicist Augustin-Jean Fresnel, and it was used in lighthouses around the world. It is composed of rings of very thin glass prisms located above and below the lamp that serve to bend and concentrate the light into a bright beam. It has been likened to a giant glass beehive with a lamp in the center.

Fresnel lenses are much smaller than their former counterparts, a difference which conferred many benefits to the designers of lighthouses because they could easily fit into more compact spaces. Physicist Jem Smallwood remarked, “Although [Fresnel] reduced the weight of the lens by a factor of ten, its optical efficiency remained undiminished.”10 The greater light transmission over long distances and varied patterns made it possible for ships’ navigators to triangulate their positions. Fresnel lenses used in lighthouses fell into six orders based on their focal length, which was determined by the distance between the flame produced by the lamp and the surface of the lens. The largest was the first-order lens, which measured six feet in diameter by seventeen feet high, and was capable of being seen for a distance of twenty nautical miles, while the sixth-order was the smallest. All of the “Sisters” lighthouses, including Point Hueneme, used the fourth-order lenses that were typically used for most coastal harbors. However, the first-order Fresnel lenses, were the most widely used around the world, and were used in the Point Conception light and the San Simeon light. Today most Fresnel lenses are being replaced by automated aerobeacons with equal visibility. Automated beacons require only occasional inspection visits to verify that the equipment is functioning efficiently. First-order Fresnel lenses are very impressive in appearance and are becoming quite rare.

Fortunately, the one formerly used at the Piedras Blancas Lighthouse at San Simeon was fully restored and is on display under a glass dome on the Pinedorada grounds in Cambria.

As fine as the Point Hueneme Lighthouse proved to be with its Fresnel lens and steam fog signal, the threatening cliffs and rocky shoals of Anacapa Island remained unlit, just eleven miles distant. Since the sinking of the Winfield Scott in 1853 on a rocky shoal off Anacapa Island, the demand for an island lighthouse was continuous. Charles Enoch Huse, a prominent Santa Barbara resident, upon learning of the tragedy wrote in his journal on December 3, 1853, “The government should build a lighthouse on those islands to light the Santa Barbara Channel. At present navigation is very dangerous.”11 Even a year before the Winfield Scott tragedy, a Coast Survey team on Anacapa Island reported the necessity of a lighthouse on either Anacapa or Santa Cruz Island, and the Lighthouse Board had recommended a $70,000 facility in 1871.

Nevertheless, because of the enormous cost of construction on the island’s sheer cliffs, the Lighthouse Board took no immediate action. Finally in 1911 a skeleton tower was erected with an unmanned acetylene beacon, and a whistling buoy was anchored five-eighths of a mile off the eastern end of the island. Nonetheless, in February 1921, General Petroleum’s tanker Liebre (7,057 tons), on her maiden voyage from San Pedro to Seattle, ran aground in a dense fog directly under the light. After waiting four hours for a high tide, the vessel, carrying 75,000 barrels of crude oil, managed to free herself and immediately headed for the Los Angeles Shipbuilding Company’s drydock at San Pedro for repairs. A later investigation determined that the whistling buoy was not in working order and that the light was ineffective. In addition, the need for a genuine lighthouse became even more urgent when a study revealed that nine-tenths of the vessels trading up and down the coast passed inside Anacapa Island.

After twenty-two years, in March 1933 a true lighthouse was finally constructed on Anacapa Island and had the distinction of being the last built by the U.S. Lighthouse Service. It was also the last major lighthouse to be built on the California Coast. The new light station, with Mission Revival-style buildings, included a fog signal building, four keeper’s quarters, a 30,000 square foot concrete pad to collect rain water, a water tank building, and a number of service buildings. The fog signal, unfortunately, functioned similarly to the one at Point Hueneme, and on an extremely foggy day shortly after its construction, the S.S. Lightbume mistook the Point Hueneme signal for the one at Anacapa, barely avoiding a shipwreck. Following this incident the U.S. Lighthouse Service changed the fog signal characteristic at Point Hueneme.12

Working or living at a lighthouse in such a precarious location as Anacapa Island could prove to be very hazardous. In November 1934 the wife of Assistant Keeper Rex Coursey nearly lost her life falling from a platform. The battleship U.S.S. California, responding to a desperate radio call from the light station, immediately sent a launch to the site and managed to get Mrs. Coursey to a medical facility on the mainland in time to save her life.

The lighthouse at Anacapa is a white cylindrical tower located on a steep cliff 227 feet above the sea, with a flashing light visible for twenty-three miles. It was originally equipped with a third-order Fresnel lens, which was automated in 1962, and eventually replaced in the 1990s with an automated aerobeacon. (The beautifully designed Fresnel lens can be viewed today at the East Anacapa Visitors Center.) Four members of the U.S. Coast Guard originally staffed the new installation and lived on the island with their families. However, with the automation of the light, all but one of the houses were removed. In conjunction with the earlier light at Point Hueneme, two beacons at last marked the northeast entrance to the perilous strait, guiding ships that entered after nightfall.13

The original Point Hueneme lighthouse operated continuously from 1874 until World War II, and over the decades was home to twelve Head and Assistant Keepers and their families. The brief tenures of the early keepers at Point Hueneme serve as a good example of the troubled state of the United States Lighthouse Board in 1874. The first Head and Assistant Keepers were both dismissed in 1878 for failing to maintain the grounds properly. Evidently, some of the personnel hired as keepers at the time had the idea their jobs were sinecures that required little energy on their part, and in fact the requirements to become a keeper were quite modest. An applicant needed to be between eighteen and fifty years old; be able to read, write and keep accounts; be able to perform the requisite manual labor; be able to pull and sail a boat; and have enough mechanical ability to maintain the premises. But the key requirement to become a keeper was to be nominated by a local collector of customs who under the Treasury Department served as lighthouse superintendent. This last requirement, with its political ramifications, best explains the inexplicable fortunes of Melvin Giles, the Assistant Keeper who was twice caught sleeping on his watch and instead of being fired was actually promoted.14

The conditions within the Lighthouse Board’s administration that could lead to such a level of incompetence are well-stated in the following 1874 lament:

It is hoped the civil service reform will make its way into this department of the government service, for the petty though important place of lightkeeper has too often been made a political prize, and thus the service, which requires performance has been injured. The politicians of the baser sort have not seldom defeated the best intentions and desires of the [lighthouse] board and ousted a good man to put in one “useful at the polls.”15

In 1789, when Alexander Hamilton was Secretary of the Treasury, Congress saw fit to place all aids to navigation, including lighthouses, into the Department of the Treasury and under the care of the Commissioner of Lighthouses. In 1820 the responsibility shifted to the “Fifth Auditor” of the Treasury, who was also responsible for all Customs collectors. As a result, each collector also became responsible for each lighthouse in his district. They selected sites for new lighthouses, were responsible for their maintenance, and hired and fired keepers.

To improve efficiency, a nine-member Lighthouse Board was created in October 1852. Over the next several decades, this new administration initiated many improvements, including the required installation of Fresnel lenses in all lighthouses and most importantly getting rid of the Customs collectors. The Lighthouse Board also established a requirement that all keepers and their assistants be issued a printed manual of their duties, the most important of which to be the lighting of the lamp at twilight and the trimming of the wicks every four hours. As a safety precaution, no lamps, wood, or candles were to be left burning. Lighthouse keepers had to continually clean the lamps, reflectors, and lanterns. The grounds were to be kept clean and wind-blown sand removed. Although not a requirement, keepers also were encouraged to cultivate the reservation land. The keepers further needed to know how to properly maintain the log book and needed to learn what should and should not be included. The Board expanded the list of prohibited actions to include leaving the station without permission save in an extreme emergency, and dispensing and selling liquor. Lighthouse inspectors visited the stations quarterly to make sure the keepers were performing their duties correctly. Inspectors were also required to record any repairs, maintenance, and improvements they thought necessary.

With respect to compensation, in the 1870s keepers received $800 per annum and rations, first assistants $600 and rations, and second and third assistants each received $500 and rations, a remuneration perceived adequate since housing, maintenance and fuel were included in the job. The rations provided included various types of meat, flour, rice, beans, potatoes, sugar, coffee and vinegar-all of which came with the option to exchange an item for an equivalently valued item if preferred.

The Board made an effort to improve the performance of the keepers by instilling pride in their appearance. All keepers and assistant keepers were admonished, “All persons belonging to the Lighthouse Service will strictly conform to the Regulations for Uniforms published by the Treasury Department.” Beginning in 1882, the prescribed uniform worn by male lighthouse keepers included a doublebreasted sack coat with five large regulation buttons on each side, a vest, trousers, belt, shoes, socks, and, of course, the billed cap with chin-strap of gold lace, embroidered with a gold wreath enclosing a silver lighthouse. Keepers also had overcoats for any cold weather. To protect these garments, keepers donned an apron when performing any messy chores. The material used for the uniform was navy blue cloth (sometimes referred to as indigo blue) in winter and navy blue serge or flannel in summer. At certain designated stations, a white uniform of similar cut could be worn in the summer. Although over the years a number of women have served as lighthouse keepers, including the first keepers at Point Fermin, the Lighthouse Board never specified a female uniform.

After fifty-eight years of service the U.S. Lighthouse Board had accomplished much of what it had set out to do, but had become quite cumbersome. In 1910, the Lighthouse Board was abolished and replaced by the Bureau of Lighthouses under the Department of Commerce, better known as the Lighthouse Service. For the next twenty-eight years enormous improvements in technology and automation took place under the Lighthouse Service, greatly reducing personnel requirements. To further streamline operations, the Coast Guard assumed the duties of the Lighthouse Service in 1939, the first time in the history of the United States that a military branch took over another branch of the government. At that time there were 1,170 lightkeepers and assistants.16

The records of succeeding keepers and the length of their tenures at the Point Hueneme Lighthouse bear testimony to the success of the new administration’s efforts. Many improvements accomplished during Charles Allen’s tenure (1894-1915), such as the change from a fixed red to an oscillating white light, and the installation of the Fresnel lens in 1897, were initiated by his superiors. However, one of Keeper Allen’s greatest successes came after personally prevailing on the government for a $2,000 appropriation to build a road from the town-center to the lighthouse. Before it was constructed, reaching the reservation with a loaded wagon was almost impossible.

The first improvement implemented at Point Hueneme by the newly organized Lighthouse Service occurred in January 1912. At a cost of $18,000, the old steam-operated fog signal system was replaced with new, modern pneumatic equipment that included twin air compressors, a fog horn, tower sirens, and a fuel storage building to house the 1,500-gallon diesel fuel tank needed to operate the engine. According to a newspaper account, the fog horn was operated automatically by “ingenious automatic devices, the Crosby operating valves.”

Numerous photographs from the early twentieth century of the greatly improved condition of the grounds surrounding the lighthouse reflect directly on the keeper’s pride in his position and in the beauty of his facility, which was also his home and a literal and figurative beacon of the community. On May 1, 1908, during the tenure of the Allen family, Teddy Roosevelt’s Great White Fleet passed the Ventura coast on its way to a two-day stay at Santa Barbara. Two thousand people swarmed to the beach, and as many as possible were allowed on the porches and verandas on both stories of the lighthouse in order to view the magnificent spectacle.

The Allens’ children also brought the family closer to the community. On May 7, 1914, daughter Melba, who was born in Hueneme, in celebration of her fourteenth birthday invited all the children of the school’s seventh and eighth grades to her home at the lighthouse. The rooms were beautifully decorated with pink and white roses from the family’s well-kept gardens.17

During Keeper Walter White’s tenure, the Lighthouse Service in 1934 replaced the hand-wound clockworks system located in the tower with an electric motor. This was a great relief to the keeper for it did away with the hand winding that had to be done every six hours. The Whites also enjoyed a complete renovation of the freshwater system at the lighthouse, which included the installation of an elevated water tank. For the local residents, the lighthouse became an even greater showplace for all to admire. The White family, who kept the lighthouse from 1927 to 1948, were highly regarded in the community and the lighthouse typically welcomed the public during their tenure. Carefully groomed garden plots of various shapes, bordered by neatly placed stones and even a fish pond showed the care with which the grounds were maintained. Photographs of the period also show garden furniture consisting of chairs and freshly painted benches with a white picket fence in the background. But Walter White’s greatest contribution during his tenure was his management of the transition from the old lighthouse to the new facilities erected during the construction of the Hueneme harbor.

Hueneme’s status as an important California seaport ended after a very successful run that lasted for more than a quarter century. In 1897, a few years after the pivotal introduction of sugar beets into Ventura County, a great sugar factory was constructed four miles north of the wharf in an area destined to be the new town of Oxnard. Within a few months, the Southern Pacific Railroad ran a spur to the new plant, spanning the Santa Clara River for the first time and sharply reducing commerce at the Hueneme wharf. The bypassed little town of Hueneme settled down to a long period of stagnation and decline.

London-born writer J. Smeaton Chase, on an eighteen-month horseback ride from Mexico to Oregon, has left us this evocative description of Hueneme during this period:

Hueneme is the ghost of a once flourishing town. On its one business street the vacant stores, with their hopeless signs of To Rent, stand ranked in shabby idleness, like a row of blind beggars. Not very many years ago this was a lively little port; but a beet-sugar factory sprang into existence a few miles to the north, and that, with its joint advantage of a railway, was too much for Hueneme. The greater part of the population and not a few of the houses themselves made off bodily to the new center, and left Hueneme nothing to boast of but its smooth clean beach and its busy past, during which (as a gloomy citizen assured me) the place had been the scene of as much traffic as “any two blamed towns of the county.” Now, only one small coasting steamer calls at long intervals, and occasionally a lumber schooner puts in with its fragrant load from the northern forests, while a stage carries scanty mails and infrequent passengers over to the railway to Oxnard, “the hated rival…”

Still the place has an air of restfulness which is pleasant, even though it be involuntary, and moreover it has a lighthouse, a modest wooden building, but, like all lighthouses, a fascinating object. As I stood on the shore in the dusk, and watched the steady beam of light streaming out over the gray wash of the ocean, there seemed something godlike in its kindly vigilance. All night it shone into the little room where I slept, throwing its moon-like gleam every few seconds upon the white wall beside my bed.18

Richard Bard, a son of Thomas R. Bard and a worthy successor steeped in the maritime tradition fostered by his father, felt a compelling need for a harbor at Hueneme. From the time he first returned home after his graduation from Princeton in 1915, it became a cherished dream. Finally in the latter part of 1925 he felt conditions were right to put his dream into action. During the next fourteen years he carried on an incredible battle to make the harbor a reality.

A bitter rivalry with certain interests in Ventura, who felt the harbor should be built in their town, lasted for four years and dashed Bard’s hopes of making the harbor a county-wide public endeavor. But Richard Bard was far from defeated by this turn of events and he began laying plans to build a privately-owned harbor to be constructed at Hueneme. During the early years of the Great Depression, the Federal Government offered funds for self-liquidating loans for private projects devoted to public use through an agency known as the Reconstruction Finance Corporation. This seemed made to order for Bard’s plans. Within a few months the loan for a harbor at Hueneme was stamped for approval. But shortly after the approval, the Reconstruction Finance Corporation was dismantled, and the government launched a new organization called the Public Works Administration.

Bard immediately instructed his agent in Washington to refile their application with the new agency. After several months of dealing with mountains of paperwork, the allotment was approved and signed by President Franklin Roosevelt. Bard was elated, and began purchasing additional acreage at the harbor site, including over sixteen acres from the Lighthouse Service, in preparation for immediate construction. But unbelievably, the allotment was rescinded because of a new regulation instituted after the funds had been approved. Bard had to once again start all over. In 1937, Richard Bard and his closest supporters succeeded in forming the Oxnard Harbor District by means of the election process. At that time it had the same boundaries as the Oxnard Union High School District, and on January 4, 1939, a bond issue in the amount of $1,750,000 was approved.19

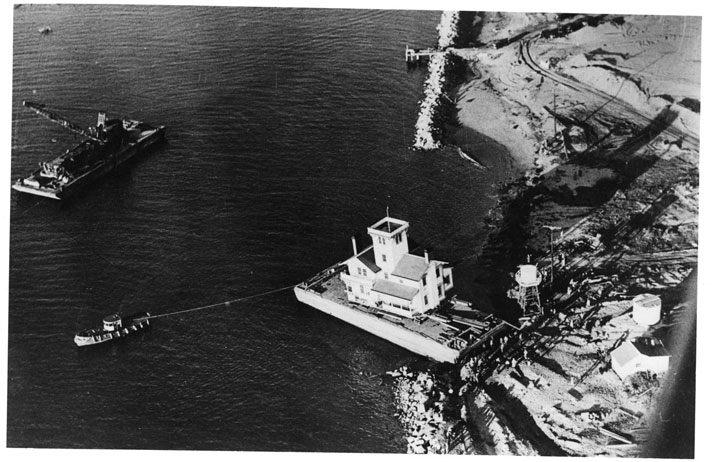

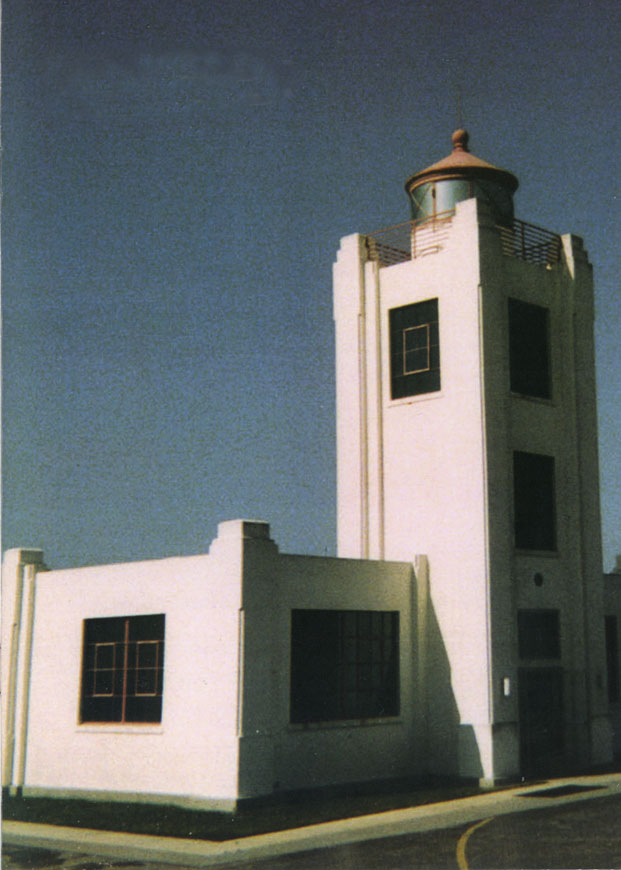

The harbor was officially completed on July 4, 1940. During the construction, many of the eager local citizens felt the name of the town should reflect its changed status. Hueneme was no longer a hamlet with a rotting wharf, bypassed by the Southern Pacific Railroad and left with only memories of greater days.20 It now had a harbor—a seaport, and its future was unlimited. Thus, the local post office conducted a poll of its patrons and on May 1, 1940, the town’s name was officially changed to Port Hueneme. When the harbor was nearing completion in January 1940, Port Director A.M. McDougall released plans for a $100,000 development at the harbor that included a yacht basin and a clubhouse. However, the news that stirred the most interest was the announcement that the club’s headquarters would be the historic sixty-five-year-old lighthouse. Because of its precarious location, the old structure, perched on the entrance channel, had to be either demolished or moved. For weeks in advance local newspapers, as well as a local radio station, heralded the Herculean effort of moving the lighthouse, stirring up community-wide interest in this unprecedented event. On the appointed day in February 1940, after a week’s delay for unexplained “technical difficulties,” a large eager crowd gathered to watch the move and a Santa Barbara radio station broadcast the event live. In addition, several newspaper reporters, photographers and a newsreel cameraman attended. After considerable mechanical difficulty, including a harrowing moment when a broken cable caused the ponderous structure to lurch toward the horrified spectators, the 104-ton building was finally swung aboard a waiting barge. Unfortunately, however, someone had forgotten to check the tide tables beforehand, and the huge weight jammed the barge onto a shallow mud flat, holding it fast despite the efforts of a struggling tugboat. To the disappointment of the throngs in attendance, the move was delayed until the next high tide calculated to arrive at 3:01 A.M. the following morning. Before the moving of the lighthouse to the Silver Strand side of the yacht basin, a temporary tower was constructed that utilized the lantern, lens and clockwork mechanism from the old structure until the new lighthouse could be built. Two new, identical residences were also built nearby on the lighthouse reservation to accommodate the keeper and his assistant and their families. The following year a new concrete, Art Moderne structure with a forty-eight-foot tower was erected at the site. Despite its contemporary style, the new tower received the original Fresnel lens from the lighthouse. The old lighthouse was moved as close as possible to its new location at Silver Strand, where it remained on the barge moored to the bank for about a week. While construction of a substantial foundation was completed, John R. Brakey, the experienced local house mover, made repairs to some minor damage caused by the move. After the historic building was firmly established in good condition at its new location, a concerted effort was made to attract members to join the new Hueneme Yacht Club, organized in April 1940 by local yachtsmen P.H.L. Wilson and Clyde Jordan, who were very enthusiastic about their new acquisition. Familiar with his organizational skills, they drew Richard Bard into the new association to help with a membership drive that proved to be quite successful. But all this came to an abrupt end on December 7, 1941. The evening following the declaration of war by the United States, reports circulated that unidentified airplanes had been heard in the area. As a result, the light at the Port Hueneme Lighthouse was temporarily blacked out for the balance of the night, off for the first time since 1874. The following day Keeper Walter White complained that he had been ordered to shut off the light, but saw no logic in it when the surrounding community was “left blazing, a perfect target for enemy aircraft.” It should be noted that the light on Anacapa Island was blacked out for the duration of the war.21

The new Naval Base was officially established May 2, 1942 as temporary quarters for the West Coast site for the U.S. Naval Advanced Base Depot, which later became the Naval Construction Battalion Center. The Navy took over the Port of Hueneme for a sum of $2,220,000 in a deal that required the Harbor District to pay off all bonded indebtedness plus interest by the year 1977. The Navy also acquired about 15,500 acres of adjacent land for the Naval Base. This was accomplished by means of a condemnation suit, a first step in an outright purchase that allowed the Navy, with a court order, immediate access to the property. The Navy rapidly built six additional docks with the capability of handling nine large ships. A total of $2,000,000 was spent on the construction of wharves and nearly $4,000,000 more for additional dredging, thirty-six miles of railroad trackage and additional warehouses. During the course of the war, the Port of Hueneme shipped over 150,000 tons of cargo each month, making the harbor the second largest shipping point for war materiel of any port in California. In summing up this remarkable accomplishment, Fortune Magazine reported, “For its money the government got what probably is the most efficient harbor in all the world.”22In 1943, after the Navy had taken over the harbor, sadly and without notification or community input, the historic old lighthouse building was quietly and unceremoniously dismantled in the quest for more space.23

With the end of WWII, the future of the harbor became the subject of great speculation throughout Ventura County. Would it remain solely a military facility or would it be made available for use as a commercial port? By 1947 the Navy agreed to lease back Dock I to the Oxnard Harbor District. It consisted of only sixteen acres of the original 322 acres taken over by the Navy in 1942. In 1960, the lease was converted into a purchase, along with twenty-two additional acres of land. In succeeding years the Harbor District acquired more land from the Navy, the City of Port Hueneme, and the Federal Government, securing a niche for itself in international maritime commerce. By 2002 the Port of Hueneme ranked first in the nation in citrus exports, first in California in banana imports, and second only to Los Angeles Harbor for California automobile imports. The present lighthouse at Point Hueneme, often referred to today as the Port Hueneme Lighthouse, performed a great service to the nation during the war, guiding thousands of ships safely into the port. In recent years the structure has been completely refurbished by the Coast Guard and it remains an active lighthouse, and also an educational facility. Since June 2008, it has remained open from 10:00 A.M. to 3:00 P.M. every third Saturday of the month from February through October. Upon entering the main floor, a visitor is surrounded by both wall and case displays, which give a museum-like atmosphere to the once bare walls and floor. Visitors can climb the winding stairway to the lantern room and view the original fourth-order Fresnel lens that still guides ships safely into port. Kim and Rose Castrobran, members of the U.S. Coast Guard Auxiliary, are available to give visitors the benefit of their expertise in all matters pertaining to lighthouses and aids to navigation. Formerly reached by threading one’s way along a rough path, fringed by riprap, today the lighthouse is approached from a flag-adorned plaza along the new 3,000-foot Waterfront Promenade. This paved and ornamentally lighted pathway, wide enough to accommodate emergency vehicles, includes three viewing sites where visitors may sit, rest, and view the scenery. Visitors might even watch a giant, thirteen-decked auto transport enter the harbor, following a course similar to that guided by the Hueneme lighthouse since 1874.24

A Special Thanks To Kim and Rose Castrobran, Hugh McCauley, Kristen Heather from the Point Fermin Lighthouse, Fred Meredith, Melinda Sturm, and all the Museum of Ventura County volunteers who helped make this project possible.

Make History!

Support The Museum of Ventura County!

Membership

Join the Museum and you, your family, and guests will enjoy all the special benefits that make being a member of the Museum of Ventura County so worthwhile.

Support

Your donation will help support our online initiatives, keep exhibitions open and evolving, protect collections, and support education programs.

- W.H. Hutchinson, Oil Land and Politics, The California Career of Thomas Robert Bard (Norman: Oklahoma University Press, 1965),Vol. 1, 72. This two-volume biography, supported by Bard’s voluminous personal records, is the best source of information on his life. Hereafter Hutchinson.

- Ibid., 135-136; George Davidson, Coast Pilot of California, Oregon and Washington, (Washington D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1889), 52. Hereafter Davidson.

- Hutchinson, 3-9.

- Bruce Roberts and Ray Jones, Lighthouses of California (Guilford, Conn.: Globe Press, 1993), 1-3; Don Morris and James Lima, Channel Islands National Park and Channel Islands National Marine Sanctuary, Submerged Cultural Resources Research Assessment (Santa Fe: National Park Service, 1996),27. Today the Channel Islands National Marine Sanctuary and the National Park Service manage the area.

- Alta California (San Francisco), 6 December 1853; 13 December 1853; 2 January 1854.James P Delgado, “Water Soaked and Covered with Barnacles, ‘The Wreck of the Winfield Scott,” (Tucson: Southwest Parks Association, 1998) reprint; John C. Wray, “The Winfield Scott,” Ventura County Historical Society Quarterly, Vol. 23, No. 3 (Spring 1978): 16-20.

- Thomas W Ward, “Port Hueneme Lighthouse, “The Keeper’s Log: The Quarterly Journal of the United States Lighthouse Society (Fall 1992): 3;”Point Hueneme Lighthouse,” Report of the United States Lighthouse Board, Office of the Lighthouse Board, US. Treasury (September 1871), 538.

- Sharlene and Ted Nelson, Umbrella Guide to California Lighthouses (Seattle: Epicenter Press, 1993), 16-20; Ward, 3; Michael ]. Rhein, Anatomy of the Lighthouse (New York: Barnes & Noble, 2000), 157-167. Hereafter Rhein; San Francisco Chronicle, 5 August 2003. The Point Fermin Lighthouse has been completely refurbished and is now under the management of the Coast Guard and the Los Angeles Department of Parks and Recreation, and has been open to the public since 2002 with the invaluable assistance of the Friends of the Point Fermin Lighthouse.

- Rhein, 161; Bruce Roberts, California Lighthouses (Guilford, Conn.: Globe Press, 1993), 405; Brady Cherry, “The Point Hueneme Lighthouse,” The Hueneme Wave (Fall 1990): 2.

- Coast Pilot, 52; Ventura Signal, 19 December 1874; Ventura Free Press, 1 January 1876.

- Rhein, 160.

- Edith B. Conkey, ed., The Huse Journal (Santa Barbara: Santa Barbara Historical Society, 1977), 45.

- Wayne Wheeler, “Anacapa Island Light Station,” The Keeper’s Log (Summer 2002): 24.

- Karen Jones Dowty, “The Anacapa Lighthouse,” Ventura County Historical Society Quarterly, Vol. 23, No. 3 (Spring 1978): 3-5; Powell Greenland, Ventura County’s Maritime Legacy (Oxnard: Ventura County Maritime Museum, 2007), 36-37.

- Ward, 3.

- Rhein, 173.

- Ibid., 39-40; San Francisco Chronicle, 25 September 1887.

- Oxnard Courier, 7 May 1914; 14 May 1914; Ventura Free Press, 12 February 1899; 12 January 1912; Ward, 3.

- J. Smeaton Chase, California Coast Trails: A Horseback Ride from Mexico to Oregon (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1913), 74-75.

- Powell Greenland, A Troubled Dream: Richard Bard’s Struggle to Build a Harbor at Hueneme, California (Port Hueneme: Friends of the Thomas R. Bard Mansion, 2006), 11-88. This is a definitive work on this period of Bard’s life, all based on primary sources.

- On September 24, 1939, while the harbor was under construction, a storm swept a rock barge moored on the beach into the wharf and completely destroyed it.

- Port Hueneme Harbor Bulletin, 12 December 1941.

- “Ports of the Pacific,” Fortune Magazine (February 1945), 146.

- Powell Greenland, “Ventura County’s Maritime Legacy, 85-89”; Port Hueneme Harbor Bulletin, 12 March 1940. Stories persist even today that the lighthouse was damaged beyond repair in the move and was, therefore, dismantled.

- Michelle L. Klampe, Ventura County Star, 21 March 2008.