By Madeline Miedema

In this Journal Flashback we continue with the second part of Madeline Miedema’s article on the Oxnard Public Library, published in the Ventura County Historical Society Quarterly, Volume 37, No.2 (Winter 1992). The article has been excerpted for brevity. Those who are interested can request the full article from the Research Library. Here Miedema details the continued commitment to children’s services and the challenges faced by the library following World War II. While the immediate post-war years saw a boom, the 1970s brought a dearth in funding. Despite that, the librarians continued to work on providing services to Oxnard’s diverse communities. We encourage you to visit the library’s locations and website!

After the close of World War II, the library resumed its normal activities. It sponsored an interesting series of talks for adults called “Authors and Readers Meet.” Every other Wednesday a local author would speak to a very responsive audience and answer questions. The program was organized by the California Library Association and the Authors Guild. It was apparently a great success but could not be continued because there were too many scheduling conflicts for the authors.

By 1949 the population of Oxnard had reached 20,000–more than double that of 1940. In 1947 the City adopted a city manager type of government, and it soon became apparent that the basement of the Carnegie Library was too small to hold all of the City staff. On October 1, 1949, the City offices were moved to the old Roosevelt School, which the city had purchased. The library quickly employed architect R.A. Polley to draw up plans for remodeling the basement. Plans were approved by the Library Board and the City Council, and in September Albert Schuster won the contract to remodel the basement for $14,986.

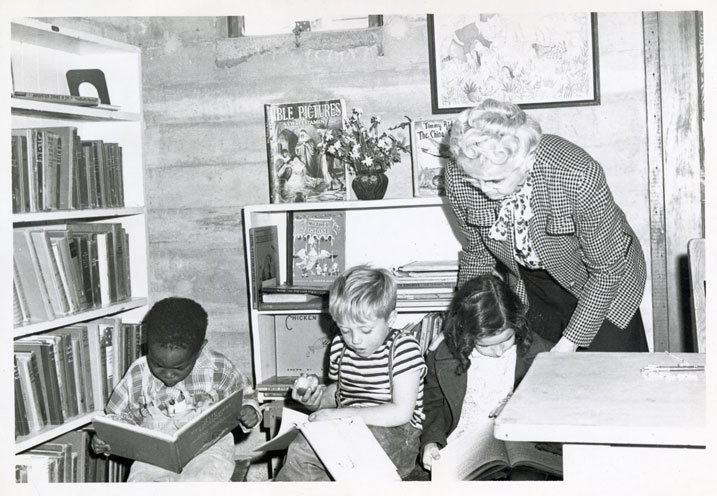

The old spiral staircase, called the “Mary Roberts circular staircase,” was finally removed from the foyer and a more conventional stairway built elsewhere. The west end of the remodeled basement became a full-fledged children’s department. Mrs. Norma Oakley, children’s librarian, was in charge. Miss Ritchen said that she wanted “a place so cheerful that they will just want to spend a lot of time there.”1 There were 16,000 children’s books, some small tables and low shelves. The east side of the basement became a small auditorium. Here the children’s story hours were held twice a week in the summer.

By 1954 television had begun to make inroads in circulation, and for a while librarians feared that TV would supplant libraries. But patrons gradually returned with a renewed interest in “how to-do” books, consumer research and consumer reports and movies, especially historical movies. Miss Ritchen said, “We at the Oxnard Library are always trying to stay ahead of the demands of our readers.”2

Early in her term as City Librarian, Emilie Ritchen put new life into the children’s story hour, the vacation reading program and the school visits. She believed that the librarian’s job offered an opportunity to bring the best literature to the young people of the community. She said that if youngsters in the first grade made an effort to come to the library regularly, they would do so automatically in years to come. 3 Probably the most important accomplishment of Emilie Ritchen during her term as city librarian was her work with children. Many Oxnard citizens today remember her visits to their elementary school classrooms to read or tell stories. It is not surprising that in 1989 the Oxnard Elementary School Board named its newest school the Emilie Ritchen School.

In June 1944 Emilie Ritchen gathered 65 children together in the small children’s room and told stories illustrated with pictures. She found the children “hard to persuade to go home.”4 It was possible to hold the story hour twice a week during the summer. A reading club for older children was organized to encourage them to read current books and to learn about the library.

All kinds of visual devices were created by the library staff to lure children to the story hour and to encourage reading. In 1947 they built a miniature storyland in the foyer of the library, complete with a castle and all the famous characters from children’s books. After a child had read 10 books, their name was placed on one of the characters. At the end of summer they could claim their character. Mrs. Oakley, children’s librarian, said, “We try to make the library a kind of magical world–because it really is.5

Other summers there were other themes, a different one each year. And at the end of vacation time certificates were given to participants in the reading program, and prizes such as a book, were given to those who had read the most books. Each year an increasing number of children received certificates. During the school year Norma Oakley and Emilie Ritchen visited schools, usually one a week. Teachers would come to the library to check out books for children in their classes, and the two librarians would then visit the classroom–mostly kindergarten through third grade–to read or tell stories.

THE GROWING NEED FOR EXPANDED FACILTIES

When the library acquired the use of the basement in the Carnegie building, the advertisement of a story hour brought 400 children one day. Emilie said, “There were so many children in the library that if you picked up your foot you weren’t sure you could get it down again.”[enf_note]Oxnard Press-Courier, May 29, 1965, p. 4 (In PC, The Weekly Magazine of Ventura County).[/efn_note] In 1954 at the last story hour of the summer there was a party with ice cream and cookies. One small boy approached Norma Oakley and said, “This is the very nicest library I have ever been in, but this is the first library I have ever been in.”6

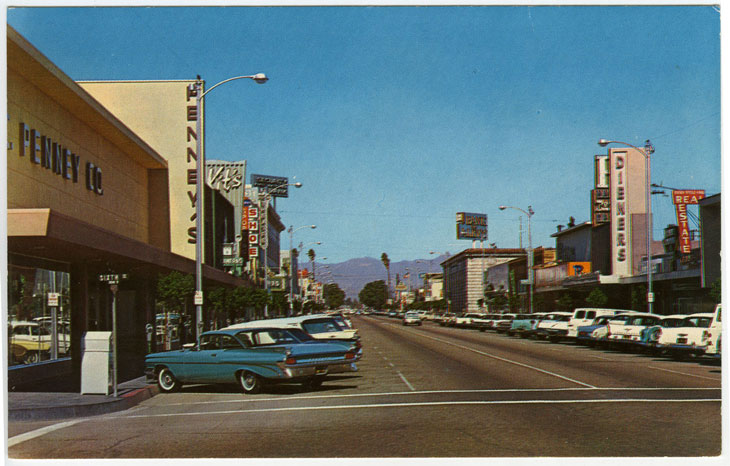

After World War II the population of Oxnard grew by leaps and bounds. By 1950 there were 20,000 residents and by 1960, 40,000. In March 1955 the Library Board minutes mentioned for the first time the need for relocation of the Carnegie Library. In 1956 a bookmobile was purchased for $6,931. It carried 1400-1600 books and in a sense served as Oxnard’s first branch library. It stopped at or near every elementary school every other week and turned out to be even more successful than originally anticipated. But the library building itself could no longer hold its growing book collection and had fallen below normal library standards.

Around 1957 the Library Board determined that a new library building should hold 100,000 books and that, “the most desirable plan would be to acquire property in the immediate vicinity of the present location and construct a modern building along simple lines…one that would lend itself to efficient, economical operation and would be built on street level to make it accessible and convenient for people of all ages.”7

The C Street site was purchased in 1961. The architectural firm of Miller and Crowell was given the contract to design the library. … In February 1963 the Library was closed for one week while a crew of staff members packed 60,000 volumes in boxes in precise order, and labeled the boxes. Jail prisoners who volunteered for the task carried the boxes to a truck which then transported the cartons to the new building, where another group of women unpacked them and placed the books on the shelves, again in precise order.

On March 1, 1963, the furnishings of the old Carnegie Library were sold at auction. The seven-foot-high bookshelves, used books, chairs, tables and a stack of old 78 rpm records were all placed on the auction block. The purchaser of the records paid $14 and exclaimed, “I have bought a gold mine.”8

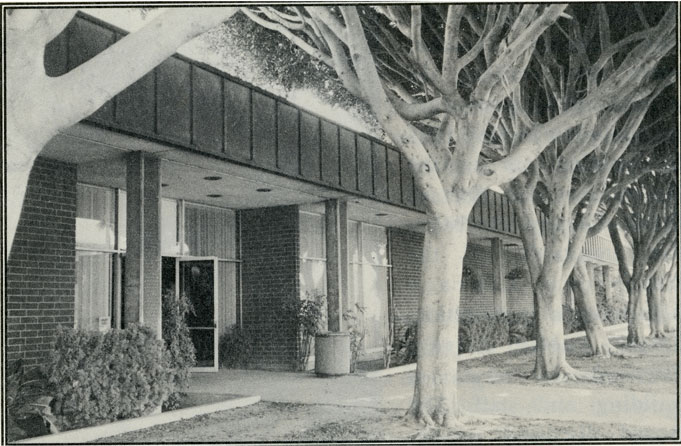

A NEW LIBRARY FACILITY

The dedication of the new building was held on Saturday, March 2. The master of ceremonies was Lee Grimes, managing editor of the Press-Courier and a member of the Library Board. On Monday, March 4, the new library was opened to the public. The newspaper said that “Miss Ritchen is presiding over one of Oxnard’s great assets.”9

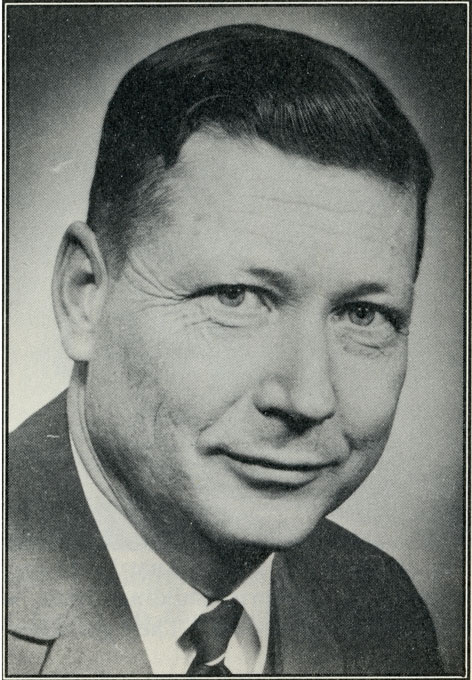

In 1968 Emilie Ritchen handed the Board her resignation, to take effect on January 1, 1969. Mrs. Audrey Lee was appointed acting Library Director until a replacement could be selected. The new director, Mr. Edwin Hughes, arrived in Oxnard in May 1968. His professional training was more extensive than that of previous head librarians since he held a Master of Science degree in Library Science from the University of Minnesota.

In February 1968, even before Emilie Ritchen retired, the Board was beginning to plan for the expansion of the five-year old library building. The Board hoped that the addition could be completed in five years. … Edwin Hughes, the new Library Director, spent time revising the policy and procedure manuals, but in May 1969 he pointed out to the Board that the Oxnard Public Library was below the standards of the American Library Association’s publication, Small Public Library Standards, in terms of building and staff. The Board discussed various options: expansion of the library building, extension of bookmobile services and branch libraries.

1970-1980: CONTINUED GROWTH; LIMITED RESOURCES

The years of the 1970s and 1980s were dominated by a desperate scramble to keep up with Oxnard’s increasing population during a period of lean budgets. A population of 71,225 in 1970 became one of 137,468 in 1990. At the same time, with the passage of Proposition 13,10 the 1978-79 budget was cut 20%.

In August 1970 the Board discussed with Paul Wolven, City Manager, the possibility of a library facility in the new Colonia Multi-Purpose Center. But it was in a meeting in November 1970 with Mr. Hosford of the City Planning Division and Mr. Hocking, staff member for planning, that the Board heard even more startling predictions. The Board was told that the small addition to the library would in no way meet the needs of the future. The planners said that the 90,000 volumes in the library should have been 184,000 in 1970. They predicted that a new main library would be needed by 1975, plus one or two branches.

In February and March 1978 the Board minutes reflect another problem. The library was found to have the lowest support of all city departments. The library director was in a lower salary classification than assistant heads of other departments. The Board, in a letter to the City Council, asked the Council to consider moving the salary of the library director to a parity with other department heads, thus “the range will recognize that the library is a major department and will add to the prestige of the department.”11

THE HOLT REPORT: A PROGRAM FOR ACTION

During the late 1970s the Board of Trustees began holding yearly joint meetings with the City Council in an effort to work out the various problems. The Council finally decided in 1978 to employ a library consultant, selected by the Library Board, to evaluate the current services and facilities of the library and to make recommendations for a future course of action. The City Council contracted with Raymond M. Holt and Associates, library consultants from Del Mar, California, to prepare a program for “Developing Services and Facilities for the Oxnard Public Library.” In 1979 Mr. Holt presented a voluminous report, A Program for Action: Developing Services for the Oxnard Public Library.

Mr. Holt compared the Oxnard Library with contemporary libraries in general and with specific libraries in particular. In the latter program of evaluation he selected nine California public libraries from nine cities of comparable size (Berkeley, Burbank, Fullerton, Hayward, Inglewood, Orange, Santa Clara, Santa Monica and Sunnyvale). Oxnard in 1978 had a population of 96,400; the nine cities compared ranged from 81,000 to 112,000. Some fifty recommendations for future action were then made.

The report stated, “Obviously, the primary reason [for the library’s problems] is the lack of adequate funding, whatever the cause thereof.12And again, “The Oxnard Public Library is among the most inadequately financed public libraries in California…”13It was found that the Oxnard Library was operating on 50% less funding than the lowest of the nine–a yearly budget of $1,013,571 for the lowest of the nine–$500,461 for Oxnard. The lowest per capita expenditure for the other cities was $8.03; Oxnard’s per capita was $5.19. The recommendation was that “the Oxnard Public Library be provided with adequate financial support equal to the needs.”14

The Holt Report also evaluated the staffing. It found the qualifications of the library staff above average and superior. But Holt concluded that “the number of staff is below any rational minimum.”15The staff at the time of the report was 17.5 fulltime equivalents–down from 22 before Proposition 13. Of the nine libraries in comparable cities, 21 was the lowest number on the staff. With such a small number the staff could not provide adequate service or develop the collections. Since there was also a lack of clerical assistance, the professional staff was doing clerical work, evidence of the report’s evaluation that there was a lack of separation between professional and non-professional responsibilities. The report recommended that the staff be gradually increased over a five-year period and be reorganized into three departments (technical services, public services, extension services) so that the skills and expertise of the staff could be used to the maximum advantage.

The report also considered the status of the library collections which it found seriously lacking in size and scope, a result no doubt of the lack of funds and staff time to devote to the collections. It found the number of books far below the accepted minimum of 2.0 volumes per capita; the Oxnard Library had 1.4 volumes per capita. Many volumes were out-of-date; 30% of the adult fiction was over 20 years old. Fiction was limited in scope, the technical collection was weak, the reference collection was adequate only for the most common questions, the periodical collection was half of what it should be and the non-print materials (recordings, videos, musical scores, microfilm, and toys and games for children) were extremely limited. The report recommended that a collections development coordinator be appointed to undertake the work of solving the above problems.

Over the next several years, the city did follow the four steps Holt outlined in acquiring a new main library: the acquisition of a site, the preparation of a program of information for the architect, the hiring of an architect and the determination of a source for funding. As early as December 1981, during a joint meeting of the Library Board and City Council, the matter of funding a new building was brought up. The final recommendation was that the construction of a new central library should be given the highest priority.

PROPOSITION 13

The Holt Report was published in 1979. The timing was unfortunate since the voters of California had passed Proposition 13 the year before. This caused local governments to reduce budgets, drastically in some cases. The Oxnard Public Library suffered along with other branches of local government. The hours during which the library was open were reduced from 71.5 per week to 62. By 1988 they had increased to 68. The sheet music program, very popular from the earliest days, was eliminated; the purchase of multiple copies of popular books was restricted; visits to schools were discontinued in 1982; the small bookmobile was retired from service in 1983; Sunday programs for children and adults were discontinued in 1984. Operating budgets, however, although still below by comparison with cities of comparable size, were nearly doubled in the 10 years from 1980 to 1990, from $641,142 in 1980 to $1,557,074 in 1990.

The Holt Report also recommended that two branch libraries be established, one in South Oxnard and one in the Colonia area. In 1974 the City had opened a Multi-Purpose Center on Colonia Road, and in 1979 one room of this center was designated the Colonia Mini-Library. This was a far cry from the 7,500 square feet recommended by Holt, but the Colonia Mini-Library is still in existence today and has a circulation of about 1,200 books per month16. Opening a branch in the South Oxnard area was not to occur until 1989.

On September 6, 1988, the City Council approved documents necessary to finance a new library and authorized the sale of bonds in the amount of $11,000,000 for construction of a new 72,000 square foot library. … The brick exterior of the new Main Library is designed to relate to several historic brick buildings in downtown Oxnard and to the new Transportation Center nearby. … The first floor of the library will have circulation services, multi-purpose rooms, [and a] children’s library. The second floor will have adult services. The building is designed to accommodate new and future forms of telecommunications. To help make the whole structure earthquake proof it rests on 80 concrete piles driven 32 feet into the ground.

FRIENDS OF THE LIBRARY

Over the years the Library Board and later the Holt Report had advocated the formation of a Friends of the Library organization. In 1970 the Board approved the request of the Junior Monday Club to form such a group, and for several years the Friends were active in providing such extras as children’s books in Spanish, large type print books, additional story hours, a poster contest in elementary schools for National Book Week, as well as programs and receptions in the library. Although the Friends became less active in the later 1970s, the monthly book sales have continued. In 1980 Mr. Hughes reactivated the organization, and the Friends have since provided again such extras as hardware and software so the library can access online databases by telephone, the money to start a video collection, a computer, a television set, and a piano. The funds for the above have been raised lately through white elephant sales, bazaars, and continued book sales.

The Holt report gives special consideration to Oxnard’s multiethnic population, especially the Spanish-speaking, in a lengthy article by Marion Foerster, library consultant, found in the appendices to the report. Attention is given as to how the library can serve the large Spanish-speaking segment of the community. Ten recommendations are given. The most important of these are the following: plan programs for the Spanish-speaking by working with organizations already serving them, organize an advisory council for the Spanish-speaking and hire a coordinator for library service to this portion of the community. A good beginning has been made in the Colonia Mini-Library and in the collection of books in Spanish already purchased, but much remains to be done. …

This article was written in 1992, shortly after the construction of the South Oxnard branch and right before the opening of the new main library on South A Street. Like many public institutions, the Oxnard Public Library faced and continues to face challenges largely due to shortfalls in funding. The library also had to learn to reach out to a diverse population. Miedema was writing when the library was in the midst of this transition. Four years later, in 1996, Dan W. Golden, the library’s community outreach program leader, published a funding plea in the Los Angeles Times. His plea included a goal of adding more Spanish and Tagalog-language books to the collection. Since then, the Oxnard Public Library has continued to provide services for children and adults, from resources for job seekers to the much beloved story time.

Make History!

Support The Museum of Ventura County!

Membership

Join the Museum and you, your family, and guests will enjoy all the special benefits that make being a member of the Museum of Ventura County so worthwhile.

Support

Your donation will help support our online initiatives, keep exhibitions open and evolving, protect collections, and support education programs.

- Oxnard Press Courier, January 10, 1949, p. 3.

- Oxnard Press Courier, January 25, 1954, p. 5.

- Oxnard Press-Courier, November 17, 1968, p. 13.

- Oxnard Press-Courier, June 21, 1944, p. 3.

- Oxnard Press-Courier, November 17, 1968, p. 14.

- Oxnard Press-Courier, January 27, 1954, p. 4.

- Minutes of the Board of Trustees of the Oxnard Public Library, April 18, 1957.

- Oxnard Press-Courier, March 2, 1963, p. 1.

- Oxnard Press-Courier, March 1, 1963, p. 8 (editorial).

- Proposition 13 (the People’s Initiative to Limit Property Taxation) was passed by California voters in 1978. The main impact of the act is limits on the tax rate for real estate. It essentially decreased property taxes by assessing the value of real estate at their 1976 value and limited annual increases. A new base year value can only be assessed in cases of a change in ownership or new construction. It also includes a range of other measure that limit tax rate increases. Prop 13 was a sign of an increasing wariness towards taxes in the late 1970s and 1980s. While a large contribution to its passage was concerns over older Californians being priced out of their homes, it had a host of unintended consequences. The change to tax policy meant less funding for local governments and public services, which impacted a wide range of institutions.

- Minutes of the Board of Trustees of the Oxnard Public Library, February 27, 1978.

- Ibid.

- Holt, p. 9.

- Holt, p. 15.

- Holt, p. 51.

- This figure is for 1992 when Miedema wrote this article.