By John Montgomery1

The great Boom of the Eighties reached Ventura County late (in 1886) but peaked along with the rest of southern California (in 1888). In this engaging article John Montgomery recounts the excitement created by the real estate Boom of 1887. That year Southern California saw a speculative bubble as agents sought a return on investments and hopeful buyers scrambled to buy land. Within the county, the boom transformed Main St. in Ventura, and saw the birth of Piru and Bardsdale, as developers hoped to capitalize on the arrival of a new rail line. Montgomery’s entertaining writing captures the frenzy of the rush, as well as the cynicism that set in when the craze, almost predictably, died out. This article is from Volume 28, No. 1 (Fall 1982). Footnotes are those of the original author unless otherwise noted. Enjoy!

If in the early seventies a sporting man had been asked to set a wager on the future capital of southern California, he would have staked his last dollar on Santa Barbara against all competitors and have thought it a sure bet. He might have gone a fraction on San Diego; but on the sleepy, humdrum, inland Town of Angels he would not have risked a bogus nickel. To ordinary vision Santa Barbara had the inside track in the race as Queen City of the South2: the protecting sweep of her coastline; the sloping amphitheater crowned by the picturesque mission; the magnificent view southeastward down the channel; the balmy zephyrs, fertile soil. All seemed eloquent to assure her the grand preeminence.

Of course, the man who saw through a millstone knew better. There are today, and ever will be, gimlet-eyed prophets boring into futurity from the wrong side and seeing coming events in the rear, who foresaw Pasadena, Pomona and Riverside hatching in the sage brush and the big cedars growing in the woods for the mammoth wharf at Santa Monica. The railroad concentration at Los Angeles was no mystery to them ere Crocker & Co. and the Santa Fe magnates had secured a week’s credit at a corner grocery3. But to ordinary mortals the southern boom was a decided surprise and many in our valley remained long incredulous to the doings of the cyclone that was whirling the solid earth skyward and threatening to make Los Angeles a veritable City of the Angels.

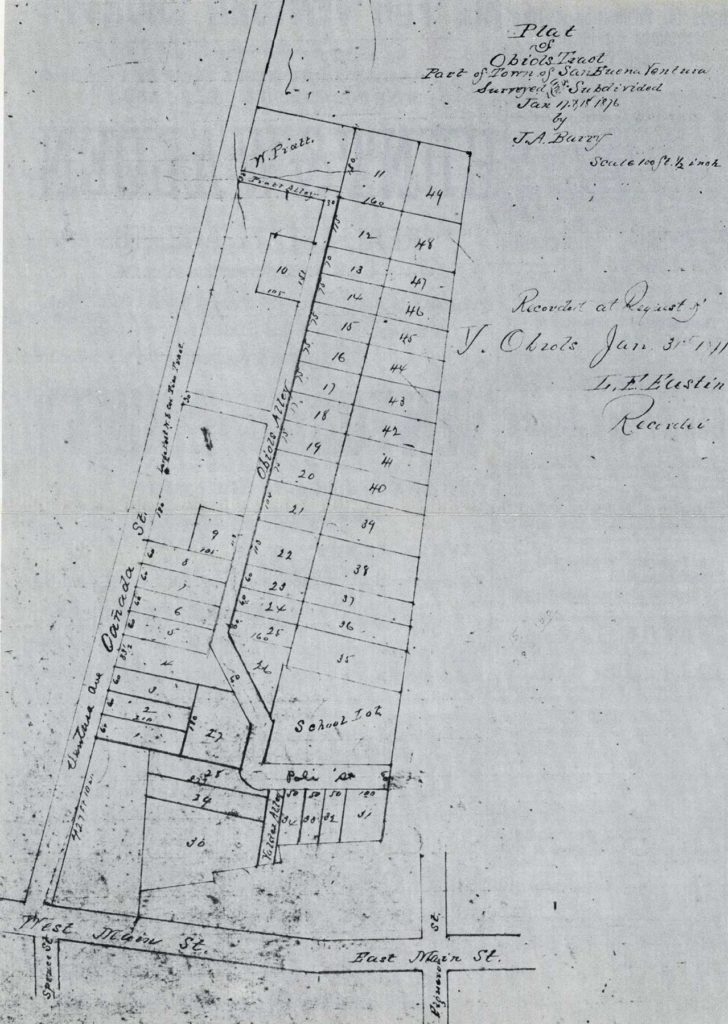

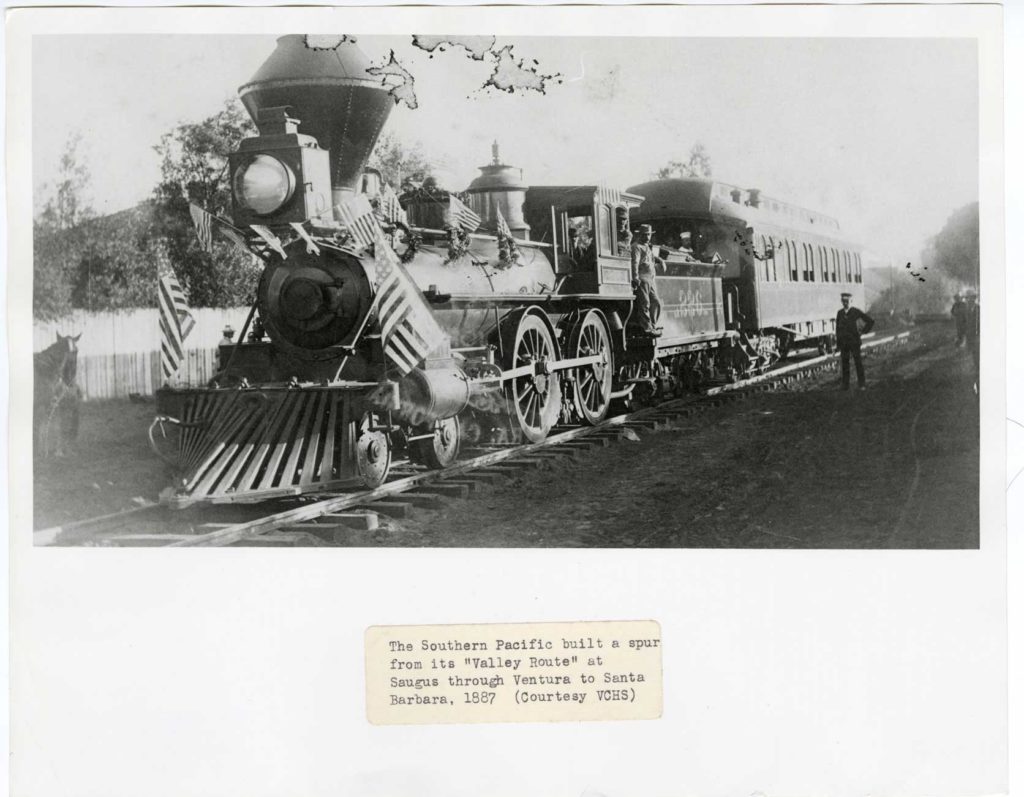

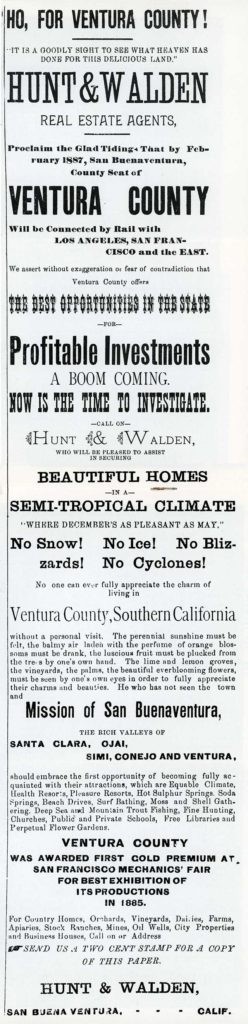

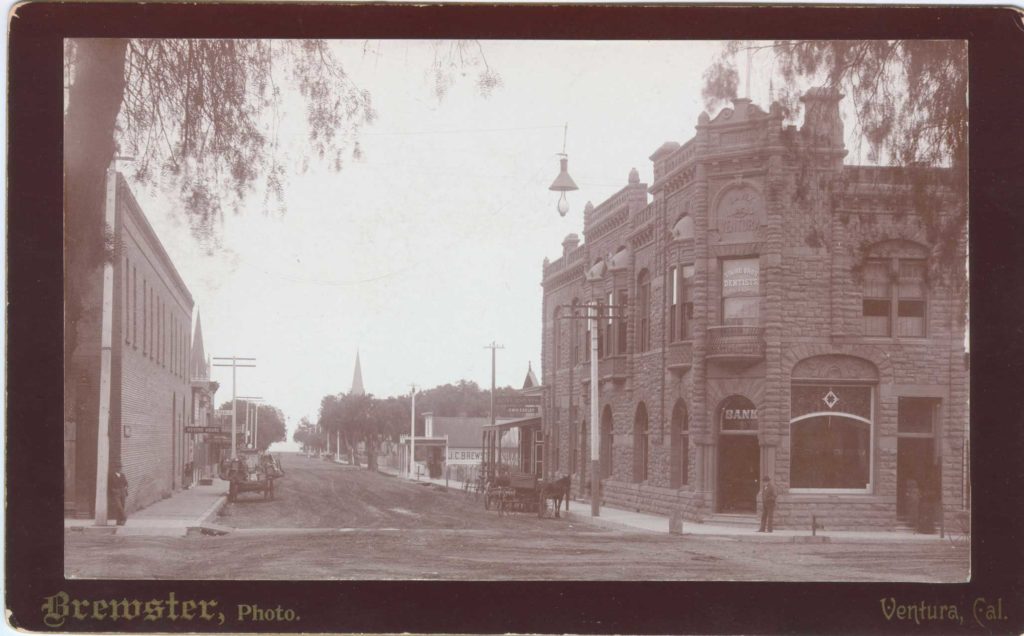

This incredulity lasted till the whistle of the locomotive vibrated among the oil tanks of Santa Paula and awoke us to a realization that the storm was coming and our valley might slip away from us in the whirlwind of excitement. The building of the line from Saugus stirred Ventura to its inner depths; the excitement of an invaded ant-hill was serenity in comparison. It was Ventura’s first boom picnic, and she made a holiday of it. Town lots took responsive jumps with the descending strokes of the spike hammers on the advancing rails; and a game of pitch and toss was played with every lot, block, and backyard within reach. Everybody wanted to grasp something and throw it off on somebody else. There seemed not enough of earth to go round. From the sun kissed hilltop to the ocean’s sands, from the dim and distant east to the far-fading west, no spot was secure from the grasp of the boom spirit.

A spontaneous growth of real estate agents (one it seemed to every front foot) cropped up on Main Street, embracing every trade, profession, and religious belief (lawyers, mechanics, liverymen, and respectable fathers of families with characters for veracity heretofore unsullied). Public and domestic duties were neglected or postponed; doctors diagnosed the boom fever and felt the pulse of the boom market, leaving their patients to nature and luck; lawyers lost no time in vain pleadings but threw the naked codes at judge and jury to hurry off to clutch some fleeting bargain; hungry husbands with one o’clock in their stomachs shed tears of disappointment on the cold kitchen-stove while their wives were out hunting a three days’ option from some obdurate lot-holder. Professions, principles, and prudence excused nobody from joining in the dance: the man or woman who was not in the deal lacked “sand.” Even the churchman, who had all his life preached the vanity of worldly investments, had to shed his wings to alight on an earthly corner lot, pending the final acquisition in Paradise.

While things were thus bubbling in Ventura, the Ojai Valley folks kept their seven senses under lock and key and sat on the lid; only when the pressure became irresistible, did the hinges burst. The first evidence at Nordhoff of the approaching contagion was the sale on Ventura Avenue of a $50-an-acre tract for $300 the acre, and the unanimous verdict was that a fool and a wise man had collided; but when the fool sold the same piece for $500 he recovered his reputation, and a new fool took his place. And thus, it was during the whole boom: a string of wise men in the rear, and a crop of fools ahead; the accumulated folly to be unloaded on the last unfortunate victim.

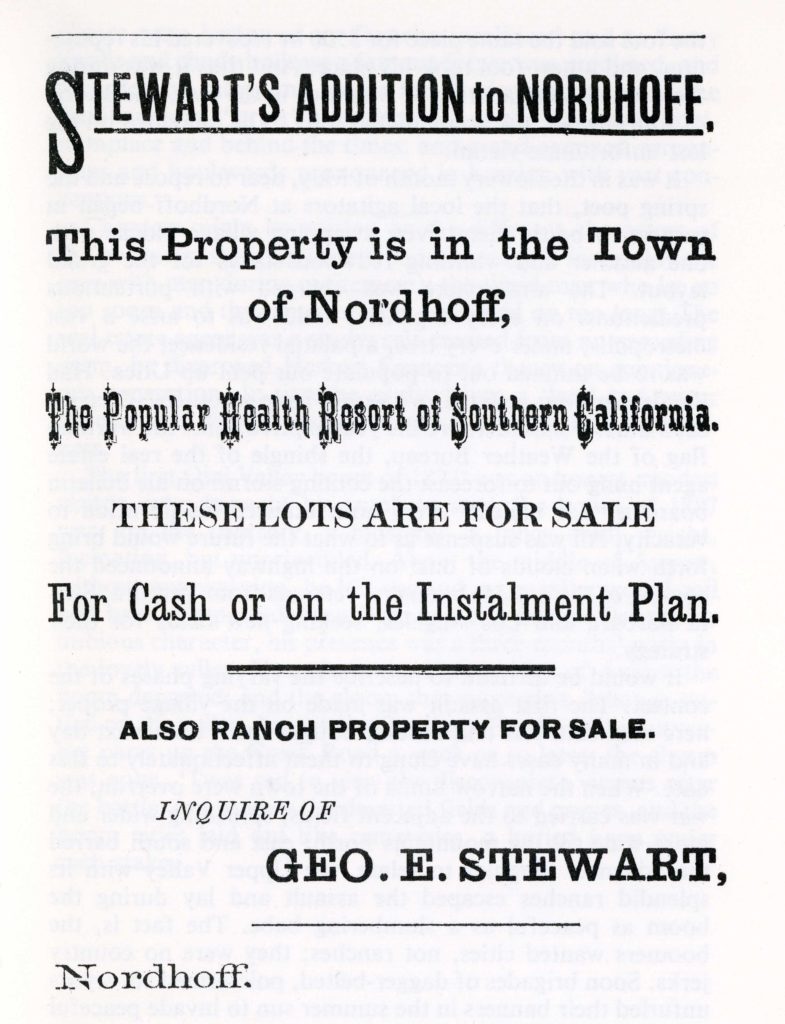

It was in the flowery month of May, dear to repose and the spring poet, that the local agitators at Nordhoff began in earnest to bestir themselves, swapping village blocks with one another and whittling redwood stakes for the grand layout. The atmosphere was charged with portentous predictions: on every expansive field was to arise a vast metropolis; under every tree, a palatial residence; the world was to be thinned out to populate our pent-up Utica4. Had the dream been realized, we would have stood five-deep on each other’s shoulders ere the year expired. Like the warning flag of the Weather Bureau, the shingle of the real estate agent hung out to forecast the coming storm: on his bulletin board a “Lie nailed” every hour attested his devotion to veracity. All was suspense as to what the future would bring forth when clouds of dust on the highway announced the coming of the outside boomers, veterans from Ventura, Santa Barbara, and Los Angeles, seeking new fields for their strategy.

It would be difficult to describe the varying phases of the contest. The first assault was made on the village proper; here, men sold lots and blocks, bought them back next day and in many cases have clung to them affectionately to this date. When the narrow limits of the town were overrun, the war was carried to the adjacent fields, spreading wider and wider till the mountains north, east, and south barred the advance. Singular to relate, the Upper Valley with its splendid ranches escaped the assault and lay during the boom as peaceful as a slumbering babe. The fact is, the boomers wanted cities, not ranches; they were no country jerks. Soon brigades of dagger-belted, pole-armed surveyors unfurled their banners in the summer sun to invade peaceful meadows and cut into sylvan groves. A rival city two miles east, and another four miles west, threatened the supremacy of Nordhoff; their suburban extensions lost in the distant landscape. A corner on redwood stakes was imminent. Pet names were bestowed on favorite localities; and to fancy knolls and shady hollows a famous future was predicted and recorded on maps and charts for coming generations. The familiar word “street” was discarded as old-fashioned, commonplace, and behind the times; and grand avenues, serpentines and boulevards pronounced in keeping with vast conceptions.

Chapters might be written on the different characters of the boomers, showing their true natures (as is invariably the case with men during excitement): the timid man who let go too soon; and the sanguine man who held on too long. The real estate agent was a study; self-created from no preceding germ, he disproved Herbert Spencer’s theory on spontaneous generation. In time he evolved into a “land and water bureau” and finally vanished with the boom into nothingness.

The first Ojai Valley boom of 18735 was an honest, modest, visitor, who brought his trunk to stay; the boom of 1887 was, on the contrary, a blusterer, a fancy swell, bright, fascinating, but unprincipled. About the middle of August, without any warning, he left us; and no coaxing would call him back. He passed away from us like a dream. Despite his dubious character, his presence was a three-month’s poem in the lovely valley. Yes, about the 10th or 12th of August the boom departed; and the gloom that succeeds a debauch settled on the valley. In vain the Southern Pacific sent a surveying party up the Creek Road a week or so later; the charm was gone. ‘Twas sad to view the disconsolate victims after the battle; sad to view the deserted fields and groves, and the boom cities laid out like cemeteries, a buried hope under each stake.

- “John Montgomery” in Thompson & West’s History of Santa Barbara & Ventura Counties, California, 416.

- Remi Nadeau showed in his City-makers, 63-72, that the rivalry was between Ventura County and Los Angeles.

- The Southern Pacific Railroad yards were at Colton, the Santa Fe at San Bernardino.

- Editor’s note: The reference is to Utica, New York, which also experienced a railroad boom and quickly expanded as a result. For a period, Utica also had a reputation as “sin city” due to political corruption.

- John Montgomery, “The first Ojai boom” in the June 14, 1893 Ojai.