Spring is in the air and in this Journal Flashback we’re sharing an article about the Bard family’s garden at Berylwood. The Bard family was instrumental in the development and growth of Ventura County, and Port Hueneme in particular. Berylwood was the family home in Port Hueneme and once hosted a small paradise. While the grounds have changed a lot since the Navy took over the mansion, remnants of the garden remain. This special double issue was originally published by the Museum of Ventura County with the Friends of the Bard Mansion. This article is from MVC Quarterly Volume 54, Number 1-2 (2012). (Note: This article was written in 2012 and contains references to trees or plants that were still there at the time of writing, but those specimens may no longer be on the grounds.)

INTRODUCTION

Thomas Robert Bard, land developer, oil magnate, bank president, local politician and U.S. senator, also created one of the first significant gardens in Southern California. Now largely unknown and inaccessible, the 62-acre estate, named “Berylwood” after Bard’s eldest daughter Beryl, served for more than sixty years as a source of wonder and delight for visitors and gardeners who rarely saw such a cosmopolitan collection of specimen trees and shrubs growing on one property. Thomas Bard lived on this land for forty-four years, until his death in 1915. The estate was often compared to a botanic garden, as it was a showplace for rare and unusual plants and a testing ground for species new to Southern California. Victoria Padilla, a historian of early California gardens, calls Bard “one of the most enthusiastic plant collectors” of the period 1900-1930, citing over 580 species and varieties of plants growing on his property.1

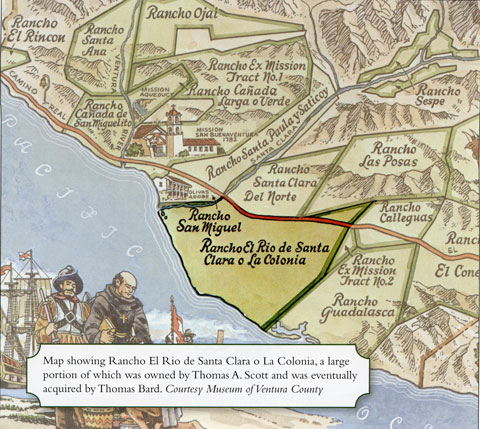

Bard came to California from Pennsylvania in 1865 to manage the property and oil interests of Thomas A. Scott, then vice-president of the Pennsylvania Railroad. Scott owned a significant portion of the former Mexican land grant Rancho El Rio de Santa Clara O’ La Colonia, located along the coast midway between Mission San Buenaventura and Pt. Mugu. In 1868 Bard acquired Scott’s land holdings, which totaled over 21,000 acres.2 Bard’s first residence was in Ojai, but in 1871 he built a small cottage on the Rancho property near Hueneme to oversee the building of a wharf there.3 He moved permanently onto the property in 1876 into a one-story, Italianate-style Victorian home built for him and his new wife, Mary Gerberding Bard, around which his first gardens were planted.4

THE GARDEN BEGINS: 1876

Born in 1841 in Chambersburg, Pennsylvania, Thomas Bard had a love of gardening that began at an early age and lasted throughout his life. His father had enjoyed gardening and probably passed the interest on to his son.5 After Bard’s father died, he was responsible for growing the family’s vegetables at their Pennsylvania home. It is especially noteworthy that the young Bard also “grew roses for [his family’s] aesthetic enjoyment,” as roses would play a central role in the gardens he created at Hueneme.6 Over the years, Bard acquired a large horticultural library on subjects ranging from garden design to California plants to fruit tree culture. He also owned many books on roses and trees, unsurprising given the amount of space at Berylwood he devoted to both.

Thomas and Mary Bard’s first house, designed by D.M. Orr,7 was a simple but elegant one-story Italianate-style dwelling with wooden siding, a low pitched roof with wide eaves, several wings, and shady deep porches on all sides. Wooden treillage lay vertically against the house for plant support. Because Bard was a prominent figure in Hueneme in the 1870s and 1880s, and he owned one of the nicer houses in Ventura County, a handsome lithograph of the house and its new gardens appeared in Thompson and West’s 1883 history of Santa Barbara and Ventura Counties.8

Bard’s first landscaping project for the property was to plant the boundaries of his new home. Before laying out the garden, Bard put in blue and red gum eucalyptus and pepper trees along the north drive and along the boundaries of Berylwood to act as windbreaks. He is probably responsible for planting the first eucalyptus trees in Hueneme in 1871 around the wharf, and may have planted the perimeter of Berylwood that same year.9 To fill in the barren plains around his property, Bard planted 40 acres in eucalyptus from seedlings. At one point he had as many as 60,000 seedlings.10 By 1883 the eucalyptus were thirty to forty feet high.11

The garden was originally laid out in the Victorian style with “gardenesque” elements. English garden designer and writer John Claudius Loudon coined the term in 1832, describing the use of exotic plants and single specimens in order to make a garden look like a work of art, distinct from nature. This new idea was a reaction to the earlier “picturesque” landscape style attributed to another English designer, Humphrey Repton, which attempted to imitate nature with its naturalistic groupings of trees laid out among lakes and broad lawns. Eastern newcomers to California in the second half of the nineteenth century brought with them the Victorian style of gardening, derived from English precedents, and prevalent throughout the rest of the United States. However, in the warmer climate of Southern California, a variation of

that style developed. The abundance of water, coupled with the technology to deliver it, the long growing season and mild climate, and new nurseries offering a wide range of exotic plants, resulted in the semi-tropical, crazy quilt display of plants seen in California Victorian-style gardens at the end of the nineteenth century.12

It is difficult to pinpoint the exact year Bard first laid out and planted the area surrounding his new house. One of the earliest existing photographs, probably taken around 1883, shows a fairly new front garden with several species of trees ranging from ten to thirty feet tall. According to journalist Charles Saylor, writing about the garden in 1931, the first plants Bard put in were heliotropes and red pelargoniums that he got from Hueneme village, presumably as cuttings.13 Foundation plantings and flower beds next to the house were full of tidy, low-growing annuals, and there was an impressive collection of imported trees. Yet the focus of the garden was distinctly outward, away from the house. Directly in front of the house were four large, round and irregularly curved sections, symmetrically placed and surrounded by curving paths. Each of the sections was composed of a lawn with several small, circular flowerbeds symmetrically placed inside, and charmingly called the “buttonholes.” The flowerbeds were made of bands of colorful annuals growing in a mass or in rings, typical of Victorian carpet bedding of the era. Similarly, tightly planted clumps of annuals and perennials such as wax begonias and impatiens lined the paths circling the lawns. Punctuating the lawns here and there were larger shrubs, while in the large round section directly in front of the house stood an Araucaria heterophylla, or Norfolk Island pine, the emblematic tree of the Victorian era in California. One still sees mature specimens today silhouetted against the sky on old homesteads and parks throughout the state.

Trees served double-duty in Bard’s new landscape. First, they grew exceedingly quickly, thanks to underground artesian wells, and provided shade where ten years earlier there was only a cornfield. And like decorative plant supports and trellises, Bard’s trees also supported a variety of climbing plants, most notably passion flowers, roses, and ivy geranium. The eucalyptus trees that lined the driveway in front of the house were luxuriantly draped with passion flowers for many years.

On the south and north sides of the house were lawns, dotted with more round beds, trees, and the occasional tropical-looking specimen, such as Yucca, Cordyline, and New Zealand flax (Phormium). A box hedge bordered the south lawn near the house as early as 1883 and became a fixture of the garden, replanted or added to as needed.

A decorative device often found in the Victorian garden was the use of wood or cast iron plant supports installed in the round beds and elsewhere. These added another vertical element to the otherwise flat look of carpet bedding and provided a place for climbers such as Spanish flag (Mina lobata), morning glory, and roses. Early photographs show these structures all around the yard as well. One small “buttonhole” bed in the front driveway contained climbing roses on tubular iron supports. Thomas and Mary Bard were clearly fond of climbing plants and had wisteria, bougainvillea, and a growing collection of climbing roses soon embowering their porches and covering the walls of the house.

The Bard garden also contained many semi-tropical plants collected from all over the world. Surrounding the beds and forming a boundary to the front garden were curved borders of spikey yuccas, palms, cordylines, and Dracaena draco, or dragon tree. Some plants Bard placed as specimens, such as a giant bird-of-paradise just off the front porch. Others he planted for a more formal effect, like the double row of fan palms that lined one of the drives. This formality hinted at a grander plan emerging on the grounds, which would be in keeping with the enlargement of the house in later years.

A vast amount of water was necessary to support all this lush growth. Bard’s property had the advantage of being situated atop deep artesian wells. Though the soil was sandy, as it was close to the ocean, both he and the surrounding community had ample reserves of water. The Ventura Signal reported as many as 30 artesian wells on the entire Rancho La Colonia in 1879.14 According to one observer in 1889, “the enormous volume of water thrown out by one of these wells soon flooded several acres of ground, and necessitated the erection of flumes to carry off the extra supply.”15 Cephas Bard, Thomas’ brother, recorded estimates as high as eight thousand gallons an hour.16 At Berylwood, sprinklers irrigated the lawns close to the house as early as 1893, and Bard had his flower beds and young trees watered by his gardener with a hose and a water truck until they were established.17

From the beginning, the garden was the pleasure grounds for the family, a place they could stroll through as well as sit in and enjoy. An early photograph from around 1883 shows a small tent at the edge of the recently-planted garden where the family could sit, protected from the sun, and enjoy the landscape around them. By 1893 the garden had filled in considerably and rustic bentwood furniture was situated under the shade of a large acacia tree on the front lawn. The paths were still visible, but the background plantings had filled in. Some of the trees were already 20 feet high, and the eucalyptus towered over all. The garden looked shady and dense. One traveler to Berylwood in 1889 helps us to visualize the splendor: “Coming in from the heat and dust the air of the place was like a perfumed bath. We rode slowly through such luxuriance of foliage and color, coming at last in sight of a rose-twined portico with delicious bits of garden perspective beyond, whose vivid tints contrasted gloriously with the adjacent forest green, and the blue-grained patch of sky most delicately revealed above.”18

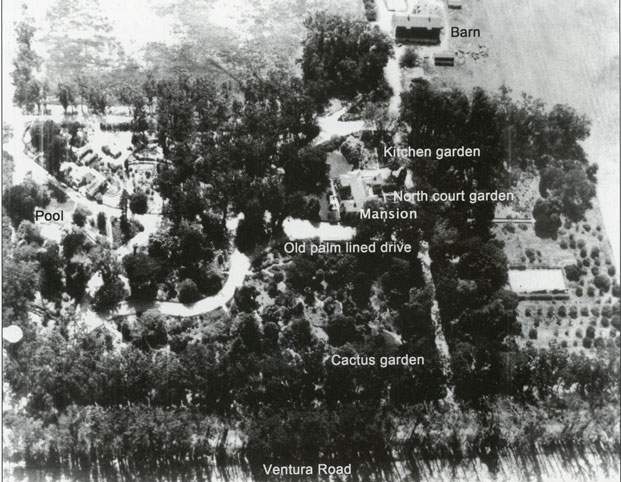

Besides ornamental plants, the family grew edibles. The north driveway bisected the grounds with the majority of decorative plantings situated on the southern side and the utilitarian gardens on the northern side. Towards Ventura Road were fruit orchards of apricot and crab apple and a grape arbor. Nearby were the greenhouse, potting shed, and a tennis court.

THE GARDENS FLOURISH: 1890-1915

Around 1890, Bard remodeled his house and added a second story and third story schoolroom for his children. The house retained some of its original Italianate elements such as the eave design, tall, narrow windows, and porch columns and brackets. The roof, however, was modified to the Queen Anne style of Victorian architecture, popular in the late 1890s and early 1900s. It became steeply pitched with a flat deck on top decorated with roof crestings. Unlike many Queen Anne houses, though, the third floor tower room was square with exaggerated corner towers and a flat roof.

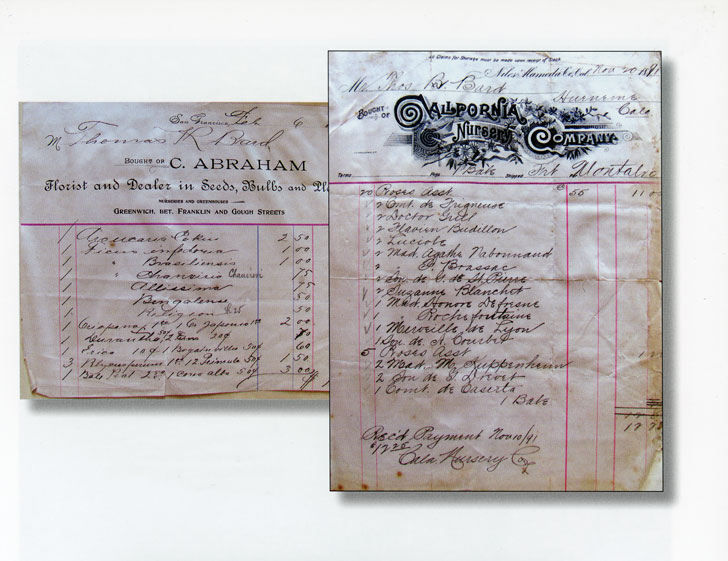

Work continued in the garden as well. During the late 1880s and 1890s Bard was intensely involved in planting. A record of invoices beginning in 1891 indicates a frenzy of plant and seed purchases. Typical seed orders were pages in length, containing purchases of trees, roses, perennials, and bedding annuals. Although one of his main suppliers was in Europe, seeds came from all over the world. For example, in one order, Bard bought three species of the Australian vine Kennedya, seven species of North American Penstemon, and seven species of Cuphea from Central and South America.19 Many of his trees were grown from seed that Bard obtained from Europe and elsewhere around the world. Based on his plant records and later tree lists, it is likely that Bard brought home seeds of English yew (Taxus baccata), Hollywood juniper (Cupressus torulosa), plum yew (Cephalotaxus fortunei), and Ginkgo biloba from Sicily in 1905. A stone pine (Pinus pinea) planted from seed brought from Portugal by a friend in 1895 may still exist on the grounds, as there are several large specimens there today. In 1891 Bard purchased seed from the Haage and Schmidt nursery in Erfurt, Germany, including Cupressus fragans, Canary Island pine, the Guadalupe Island cypress of Baja, California (Cupressus guadalupensis) and C. lusitanica, the Mexican cypress.20 It is entirely possible that Bard was growing these trees before Francesco Franceschi, the well-known Santa Barbara nurseryman, began offering them in his 1897 catalog.21

Bard did, however, order a number of plants from Franceschi and other Santa Barbara growers such as Peter Riedel, the City Nursery, State Street Nursery, and Exotic Nurseries of Santa Barbara, and from Theodosia Shepherd of Ventura. From the Exotic Nurseries, run by the Lejeune brothers, he purchased two California live oaks (Quercus agrifolia), thirteen native Woodwardia ferns, a native California cherry (Prunus ilicifolia), and several conifers.

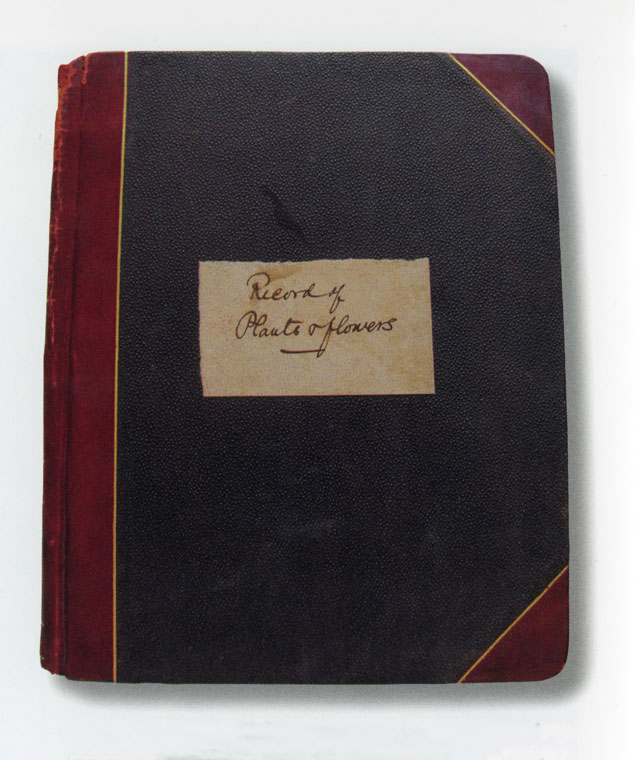

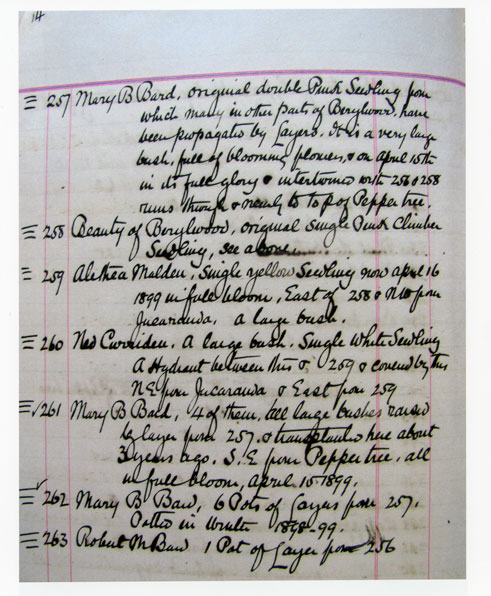

Bard maintained several journals on the plants he grew at Berylwood. One, compiled as he walked around the garden from 1908 to 1914, recorded the location of each plant in relation to the previous one. Two other journals he devoted to roses. These books, along with a list of plants created in the 1930s, paint a fairly comprehensive picture of the diversity and number of plants growing in the Bard garden. Oxnard agriculturist T.F. McFarland advised writer and naturalist Charles Francis Saunders in 1914 to visit Bard for information on California plane life, noting he had “undoubtedly the most variety in his garden of any place in Southern Cal[ifornia].”22

From the beginning, roses were a feature at Berylwood. Bard ordered typically large quantities of roses from nurserymen around the country, including Ellwanger and Barry, Henry Dreer, and Peter Henderson, all East Coast companies. Bard ordered sixty-two roses from the California Rose Company in 1910. He began to catalog his roses in 1894, and by 1913, in his second rose journal, he listed over 800 individual plants. Most were old shrub roses and climbers including “Gold of Ophir,” “Sombreuil,” “Paul Neyron,” and “Madame Alfred Carriere,” which adorned walls and trellises around the house and many trees in the south and front lawns. Bard enjoyed hybridizing roses too, and named seedlings after members of his family. “Robert M. Bard,” named for his deceased son, was a double cream-colored climbing rose, which Bard called the “finest of all.” A pink-flowered climber, “Beauty of Berylwood,” formed a 15-foot dome that Bard scaled by ladder in order to pick the blossoms. “Clara Bard,” a single yellow rose may have been a sport of “Gold of Ophir.” In a letter to Mary, whom he called “Mollie,” Bard describes their blooms: “I think they are very beautiful and noticed that they are very much like old Gold of Ophir roses. I was surprised to see the resemblance and that these old Ophirie roses lose the pink tints and markings-but the seedling has deeper yellow in the center are very fragrant.”23

Over the years the garden grew larger, more densely planted and thus more defined by separate areas. It lost most of the flatness seen in the earlier Victorian carpet bedding and as it matured upwards, new enclosed spaces were formed. In the sandy soil with the artesian waters below, trees that survived grew incredibly fast. The Norfolk Island pine grew to meet the edges of the circular island in which it stood. It was a spectacularly healthy tree with a branch spread of about 50 feet. Next to it was a less common Araucaria cunninghamii, or hoop pine, a native of Queensland, Australia. The blue gum eucalyptus on the driveway near the front of the house had a girth of 24 feet before 1915 and now measures over 27 feet in circumference, over 100 years since it was planted. These tall trees provided very deep shade along the paths that bordered the lawn areas, and under each were planted smaller shrubs and perennials, such as ferns, to provide a lush and layered effect.24

The planted garden areas extended out from the house to the northeast, along the east side of the property to the eucalyptus boundary, and south towards the ocean. In addition to the north drive that ran from Ventura Road out to the barns and fields, a grand driveway wound through the property. From the southeast gate, this main driveway led to the house, cutting through the property diagonally to the northwest. The driveway encircled several small islands of trees and shrubs (probably the former Victorian-style beds) and for some time was lined with California fan palms (Washingtonia filifera) and large shrubs such as Plumbago capensis and germander (Teucrium fruticans).The driveway also forked to the south and led to a small cottage, built in 1910, that became son Richard Bard’s family residence in 1916.

In addition to the large gardens on the grounds around the main house, there were smaller specialty areas such as the “aralia walk,” the “lantana walk,” and a rockery. A fern bed contained ferns such as Polypodium, and included shade plants such as Solomon’s seal, trilliums, salmonberry, coral bells, and tiger lilies. Between the planted gardens near the house and the family orchards to the north lay an area referred to in later years as the “Wilderness.” The wilderness concept dates back to late seventeenth-century England and describes the creation of wooded areas of trees and shrubs with paths for strolling. A wilderness might be a grove of trees that acts as a transition to the wild landscape beyond the property or serves more formally as a “natural labyrinth supplying in the landscape garden that element of mystery and surprise provided in earlier gardens by the formal maze.”25 While it is uncertain why Bard planted his wilderness, or if he himself called it that, it is clear that it contained many species of ficus, conifers, eucalyptus, acacia, palms from all over the world, and native trees such as California bay laurel, Torrey pine, and California fan palm. Several of these trees are still standing today in what is now a parking lot, although the area has lost the density and shade provided by the numerous plantings that once existed there.

THE MANSION AND SURROUNDING GARDENS

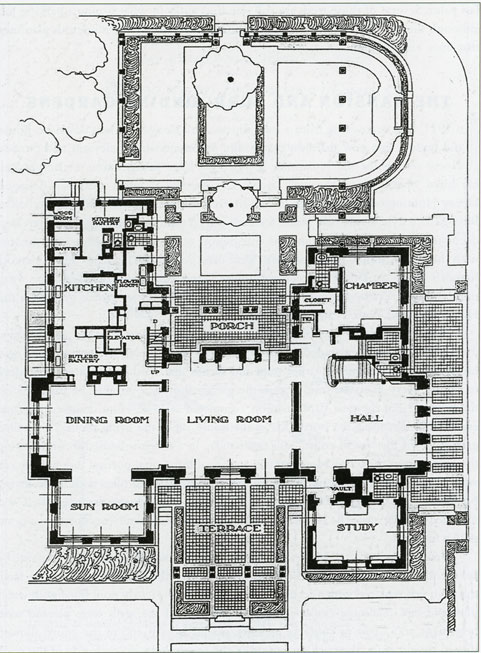

In 1911, after recovering from a long illness, Bard decided to tear down his house and build a fine new mansion that would accommodate an elevator and provide a new setting for the remaining years of his large family’s time at Berylwood. He hired Myron Hunt, the well-known Los Angeles architect who had designed Henry Huntington’s great estate in San Marino the year before. Built in the Italian Renaissance style, Bard’s new house featured stucco walls and a tile roof, tiled terraces, decorative dentil cornices, and the integration of the outdoor spaces and gardens with the house. Simple Doric columns were used on porches, terraces, and as pergola supports in the gardens. These echoed similar Doric columns Hunt used at his own, more Arts and Crafts-style home built in 1905, and also in the garden pergola at the Hotel Maryland, both located in Pasadena.26

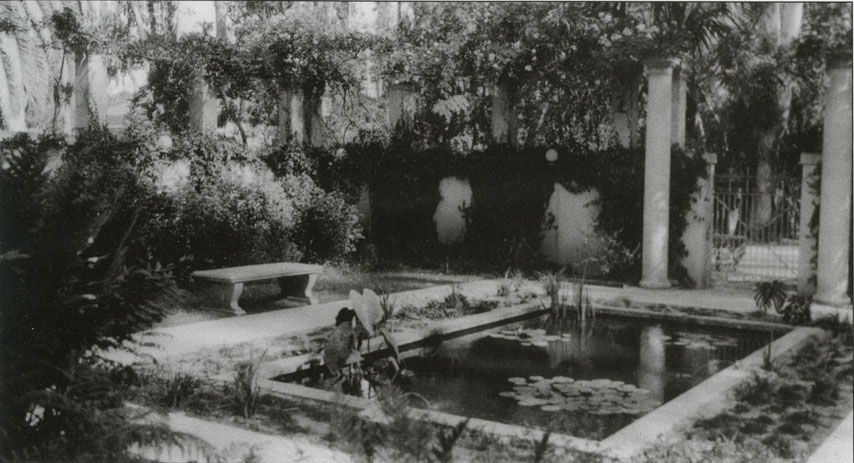

Hunt designed many landscapes for his clients, and it is clear from the plans he drew for Bard that Hunt contributed significantly to the areas directly surrounding the new house, while incorporating earlier trees and shrubs that Bard had planted. According to Hunt, “every line seen from within the garden should, if possible, be parallel with the house.”27 For the new Bard mansion, completed in 1912, Hunt designed a formal enclosed garden along the north side of the house, off of the living room. This walled garden, called the “north court,” still exists today in a much-modified form. Entering the garden from the living room terrace, one faced the central portion that was on axis with a gate in the wall. Just off the porch was a rectangular bed filled with shade-loving perennials, seen in old photographs. It is not clear from Hunt’s drawings what was intended for that area. The bed has been changed and is currently occupied by a pond with a fountain.

Beyond the bed and down several steps was a rectangular space that contained a lawn with a jacaranda tree and small plantings around the perimeter. Sometime later, the lawn was replaced with a rectangular basin to create a lovely pool filled with water lilies and taro (Colocasia esculenta). Beds at the base of the walls were planted with perennials, and a pair of concrete benches, placed at each end of the court, allowed one to sit and enjoy the trickling sound of the four spigots on each side of the pool. Between the pool and the upper bed was a tall queen palm (Syagrus romanzoffiana), most likely a remnant from the earlier gardens on the north side of the former house. Bard’s plant book of 1909 notes several queen palms in that general location, one of them being 35 feet tall, and photos of the new construction show a mature tree.

In the Bard’s day, half columns draped in climbing roses topped the walls while the inside walls were planted with Virginia creeper (Parthenocissus quinquefolia). Seven freestanding columns bisected the lawn at the opposite end of the court from the pool, supporting more climbers and echoing the vertical strength of the Irish yews chat flanked one of the benches. Outside the north court were further elaborate plantings. Several layers climbed up the walls, beginning with sword fern along the ground, Virginia creeper climbing above, and clipped evergreen balls adorning the tops of the walls, mingling with the roses.

The south side of the house provided other new landscaping opportunities. Hunt designed a terrace to take advantage of the sun, which was partially enclosed by the wings of the house, and he installed more pairs of Doric columns. Connected to the columns were pipes with wire strung between them to provide copious support for climbing vines. An informal lattice was mounted on the downstairs walls of the southwest corner so that wisteria vines could climb up the house, a feature seen at the mansion as well as all of Bard’s previous homes. At the end of the terrace were flowerbeds, two tall Irish yews, and the large south lawn enclosed by a box hedge, portions of which edge the terrace today.

South of the mansion among eucalyptus and pine trees was a smaller bungalow that served as temporary quarters for the family while the mansion was being built. This rustic bungalow had several porches and patios covered with pergolas to support climbing plants. In 1916 Thomas’ son Richard moved into the bungalow with his new wife and they created interesting gardens that complemented the overall grounds.

“Mother loved pergolas,” Richard’s daughter Joanna Bard Newton recalls, noting the wisteria that that grew all over them next to the house.[enf_note]Joanna Bard Newton, personal comment to author, 2000.[/efn_note] A remnant of another pergola is located a short distance away from the house and former swimming pool, and recently still supported a tangled old vine. As around the main house, box and privet hedging was planted to partition a formal cutting garden, to edge paths, and to encircle other small areas, such as an aviary. This house was remodeled and enlarged several times.

Thomas Bard lived in his new house for only three years, passing away in 1915. He had finished his senatorial term in 1905 and suffered from bouts of poor health. His garden, however, provided him with times of great pleasure. In a 1912 letter to his sisters in Pennsylvania he states,

It is not because I love my garden more than you, that I give it more attention, but because it is ever inviting one to choose the pleasures that are nearest at hand …. I count it good fortune, that I find it interesting all the time to look after the plants & trees, to propagate those I like, and to plan for the planting of the new plots. Gardening, family history and solitaire are called by the children my fads that keep me from getting old too soon ….

Thomas Bard to sisters, 27 October 1912, courtesy of Georgia Pulos and Joanna Bard Newton.

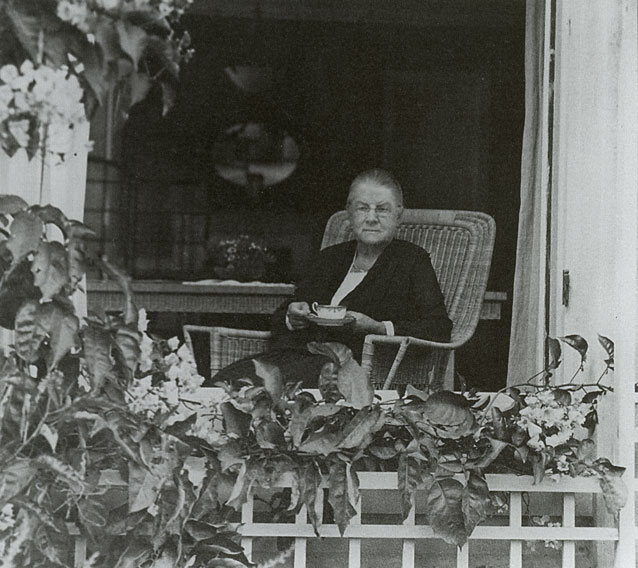

Thomas Bard’s death did not bring the end of garden planting and maintenance at Berylwood. For the remaining years that Mary Bard lived there, she actively purchased and planted new specimens, corresponded regularly with horticulturists and botanists on plant identification, and, with the help of family friend Florence Bolton, made an attempt to catalog the existing plants on the estate in a card file. Invoices from Bard’s papers indicate a cactus garden was put in later, probably in the late 1920s. Extant lists show 75 genera of succulents and cactus, ranging from Agave to Zygocactus with numerous individual species.

A WIDER INFLUENCE

The rarity and abundance of Bard’s plants and his precise documentation of them distinguished the Berylwood gardens. Numerous testimonials from botanists and horticulturists all over the country vouch for Bard’s singular choice of plants. Peter Barnhart, a keen horticulturist from Los Angeles and editor of The Pacific Garden magazine, took a great interest in the Bard garden and visited often. Referring to cuttings of Hedera chrysocarpa, the yellow-fruiting poet’s ivy of the Mediterranean (Hedera helix f. poetarum), Barnhart wrote to Mary Bard in 1923, “Certainly your ivy is the only specimen that I have met with in all my travels over these United States.”28 Eric Walther, Park Botanist for San Francisco said in 1936, “We are very glad to get these [cuttings], as I know of no other specimen of Dendropanax arboreus in this country.”29 Bard’s specimen of Bomarea caldasiana, a lovely vine with pendulous clusters of red and yellow flowers, was also the only known specimen in California. In 1928 Peter Barnhart suggested Mary send horticulturist L.H. Bailey of Cornell University a cutting for his herbarium because Bailey had, according to Barnhart, never heard of it, although it had been introduced in England in 1863.30 Both Eric Walther and Hugh Evans of Evans and Reeves Nursery in Los Angeles collected the vine from Berylwood in the early 1930s. It was then introduced to the nursery trade in Northern and Southern California, and was apparently very successful in Golden Gate Park.31 Other rare plants included Ehretia dicksonii, and the cypress pine (Callitris preissii [C. propinqua]), “rare even in Australia” where it is native, according to Barnhart.32 Mary Bard and friend Florence Bolton sent cuttings of these to such distinguished herbaria as the Bailey Hortorium at Cornell, the Arnold Arboretum at Harvard, and the California Academy of Sciences in San Francisco for identification and deposit.

Beginning about 1923, Bolton began sending specimens of plants from the garden to Alice Eastwood at the California Academy of Sciences for her to identify, and Eastwood encouraged Bolton to publish a list of the plants at Berylwood. As an expert on cultivated plants, as well as native California species, Eastwood was in a position to assess the Berylwood collection: “I know that there are so many things in the Bard place that are nowhere else in California and so many will be interested in seeing them.”33 For a flower show held in 1924 at the Academy, Bolton sent Eastwood sixty-five uncommon specimens. According to Eastwood, “the exhibit from Berylwood contained more plants new to those who came to our show than any other exhibit and added greatly to the success scientifically and artistically.”34 In the 1930s a 15-page list of plants growing at Berylwood was prepared, presumably from the card file, for forester Woodbridge Metcalf of the University of California Agricultural Extension Service in Berkeley.35 This list became the main source for horticulturists and historians around the state interested in the Bard garden.

In the mid-1920s a number of factors were responsible for the creation of several public botanic gardens and arboreta in Southern California. The continued population growth, the enthusiasm with which new plants were imported and tried in gardens, a substantial group of wealthy philanthropists, and the need to educate the public about gardening practices in the varied and large state contributed to the establishment of both native plant gardens, such as the Santa Barbara Botanic Garden in 1926, and more exotic ones, such as Henry Huntington’s estate-turned-botanical garden in San Marino, and the short-lived California Botanic Garden, established in 1927 in Los Angeles.

From 1927 to 1930 Mary added some of these local gardens to her list of institutions around the country that received cuttings from her estate. ln 1927 Ralph Hoffmann of the Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History collected nearly 100 specimens, “all rare and extremely interesting,” from the Bard Garden for the herbarium of exotic plants at the museum (now housed at the Santa Barbara Botanic Garden).36 Mary also became a member of the newly-formed California Botanic Garden and sent a number of seedlings to the director for trial in their new location in Mandeville Canyon in Los Angeles. Many did not survive the first two years, but if any did, they may well be growing in private homes in the canyon today. Unfortunately, the garden failed due to a lack of funds and closed in 1929, after only two years.

THE COMMERCIAL NURSERY

From 1931 to 1932, Thomas and Mary’s son Richard began a small commercial enterprise on the estate co sell a number of extra plants. Known as “Berylwood Gardens,” a small activity of the larger Berylwood Investment Company, which Richard Bard oversaw. ln a letter to landscape architect Katherine Bashford of Los Angeles, Bard explained the new venture’s purpose: “In order to make room for our choice trees and shrubs in our gardens, we decided to eliminate some of the undesired shrubs and trees, likewise some of the rare specimens of trees of which we have duplicates.”37 A.W. Smith, whom Bard called an “over enthusiastic gardener,” directed the nursery operations and was to sell all excess inventory.38 In hopes of selling the entire lot at once, Smith contacted landscape architects and nurseries known around Southern California for growing and using rare plants. While none wanted to purchase in those quantities, Smith did establish accounts with the Southern California nurseries of Paul Howard and Coolidge Rare Plants, national retailer S.H. Kress & Company, and landscape architect Florence Yoch in Pasadena.

Some of the 3,500 trees and shrubs that were available included magnolias, acacias, eucalyptus, giant bird of paradise, bamboos, phormiums, palms, and Hibiscus, along with a variety of bulbs such as Clivia and Agapanthus and the more uncommon Vallota and Velthemia. Some of the bulbs Thomas Bard had bought from South Africa in the 1890s. Invoices from some orders from Berylwood Gardens give a sense of the size of the production. Quantities ranged from 1 specimen (redwood) to 10,000 (Montbretia bulbs). S.H. Kress & Company in Los Angeles was a regular customer, buying 500 Amaryllis bulbs, 550 tritomas, 350 aloes, and 200 petunias per order.

In order to move the plants out, Smith conducted an aggressive letter-writing campaign, trying to sell either specimen trees or entire lots of plants, and coaxing growers such as Paul Howard to come to visit Berylwood Gardens. He also wrote directly to estate owners who collected plants, including Mrs. E.L. Doheny, wife of oil tycoon Edward Doheny, famous for his unparalleled collection of rare palms and cycads. Smith offered Mrs. Doheny shaving brush palms (Areca sapida) from Africa that Bard had planted in 1892.39 Whether or not she purchased them is unknown.

The Berylwood Gardens nursery venture was short- lived. Letters from early 1932 indicate the operation would shut down that summer “due to reconstruction of the Bard estate.”40 One of the greenhouses was sold to John Merriman of Ventura in May 1932. Although director A.W Smith made every effort to keep himself employed at Berylwood maintaining the garden and nursery, Richard Bard wanted the plants sold.41 Smith’s contract was limited to caring for and selling the nursery plants, which he attempted to do until October 1933, when his contract ended.42 Beginning in 1934, Mary Bard began to spend winters in Ojai where she had just built a new house, and some of the plants were probably shipped there.43 Mary Bard died in 1937, leaving her son Richard in charge of both the Berylwood Investment Company and the estate.

THE GARDEN TODAY

In 1944 the U.S. Navy leased and eventually purchased the 62-acre Bard estate for its Naval Construction Battalion Center. The commanding officer moved into the Richard Bard house and the mansion became the Officers’ Club. According to Thomas Bard’s daughter Beryl, the Navy retained one of the family’s grounds workers to keep up building and garden maintenance. Unfortunately, as she recalled in 1947, “he knew nothing about plants & gardens … [and] I don’t know what has died or not been kept going right-and since the drainage district that was last put in a few years ago, has been operating, the water level has gone down & many gum trees have died.”44 Maunsell Van Rensselaer, director of the Santa Barbara Botanic Garden, visited the grounds in 1947 and collected specimens of existing trees for the Garden’s dried plant collection of exotic species, so a partial record of the garden shortly after the Navy took over exists.

In order to develop a maintenance plan for the existing trees and shrubs, the Navy inventoried the grounds in 1972. Over 665 specimens were counted, including 241 blue gums (Eucalyptus globulus) and 91 various pittosporums.45 Yet as garden owners change, so too do garden spaces. In the north court, the columns are gone, and the pool has been replaced by various perennials and clipped privet standards. The once charming vine-covered walls and columns and the gently curving shapes have given way to a simpler, plainer, and more utilitarian appearance, reflecting the later use of the building and grounds as an Officers’ Club. The Navy enclosed and converted the formerly vine-draped south terrace to a dining area. Out on the grounds to the south and east of the mansion, the individual beds, paths, and special little gardens are gone, replaced by new Navy housing and lawns.

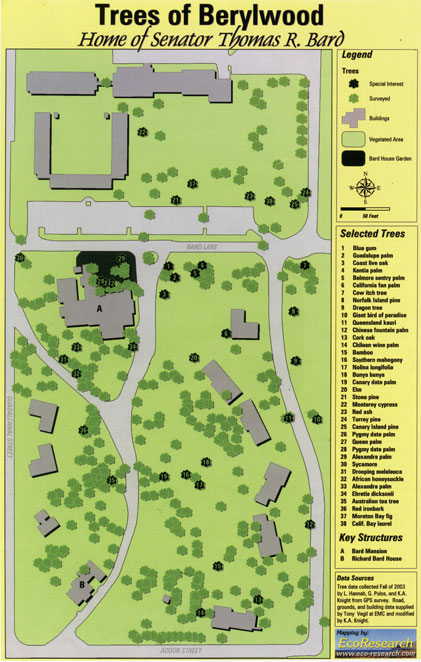

Many of the trees are still standing, however, ranging in age from 95 to 135 years old. A 2003 inventory, sponsored by the Garden Committee of the non-profit Friends of the Bard Garden, listed over 405 trees and large shrubs, many planted during the Bard family’s ownership of the estate.46 By studying their layout, one can imagine how they were grouped along the driveways or centered in garden beds. It is still possible to grasp the variety of plant species that Band grew, and how he would have enjoyed being out in the garden with his large family. However, because the gardens are located on a Navy base and access is difficult, few people ever get to visit, and the gardens have largely faded from memory.

Although much has changed on the property since the 1940s, efforts are underway to preserve the remaining trees, hardscape, and garden features and to restore a small portion of this once-grand estate. Today the Friends of the Bard Mansion and the Navy are working collaboratively towards the restoration of the north court water garden, with the goal to restore the pool and reconstruct the columns and plantings as they were in the Bard family’s day. The Navy has also undertaken a tree health assessment in recent years.

Thomas Bard’s garden was one of the earliest significant gardens in Southern California. It is an amalgamation of 70 years of gardening styles as they manifested themselves in the new state of California. Although Bard’s houses went through several transformations, the garden was not begun anew each time. It slowly evolved from its Victorian beginnings to a more naturalistic style as plants matured and trends in garden design changed. Formal elements were added, yet it still retained its eclectic feeling. Unlike many other wealthy homeowners of the 1920s, who looked to Italy and Spain for inspiration for their gardens, Bard’s preference apparently remained with an earlier, less formal style of planting, exemplified by trees, buildings, and pergolas draped with fragrant boughs. Being the keen plantsman that he was, Bard was probably more concerned with finding suitable places to raise all his new acquisitions than with an overall design. As a plant collector and exchanger Bard had a noticeable impact on the nursery industry in California, providing plant material of unusual and uncommon species to nurserymen who then propagated it for the trade.

The gardens at Berylwood enjoyed statewide recognition, and writers referred to them often in horticultural publications as well as local newspapers. To recognize the importance of Thomas Bard’s contributions to California and the significance of his home and garden in Port Hueneme, Berylwood was nominated to the National Register of Historic Places in 1977 and named California State Historic Landmark No. 31 in 1978.

Make History!

Support The Museum of Ventura County!

Membership

Join the Museum and you, your family, and guests will enjoy all the special benefits that make being a member of the Museum of Ventura County so worthwhile.

Support

Your donation will help support our online initiatives, keep exhibitions open and evolving, protect collections, and support education programs.

- Victoria Padilla, Southern California Gardens: An Illustrated History (Los Angeles: University of California, 1961), 106.

- John C. Peterson, Berylwood: The Bard Estate at the US. Naval Construction Battalion Center, Port Hueneme, California (Hueneme, Calif.: U.S. Department of the Navy, U.S. Naval Construction Battalion Center, 1963), 2.

- Ibid., 11.

- Ibid., 9.

- Michaela Crawford Reaves, “Doctor C.L. Bard: Soldier, Pioneer, Doctor,” Ventura County Historical Society Quarterly, Vol. 45, Nos. 3 & 4, (spring and summer 2000): 6.

- Ibid., 7.

- David McDill Orr, architect, b. c.1834, Ohio, did in fact reside in Ventura County, but only for a short while. He registered to vote in 1876, the same year he supervised the construction of Bard’s second house on the property. By 1879 Orr had built another Italianate-style house for Dr. James Kelly in Golden, Colorado. In 1885 Orr oversaw the construction of a house for a W.C. Ellis in Denver, Color ado. Orr died in that city in 1894. See http:/ /trees.ancescry.com/ tree/ 30053930/ person/12237162492; Great Register for Ventura County), 1873-1878 (handwritten index, Research Library, Museum of Ventura County), Ventura Signal, 8 April 1876, 3; Ventura Signal 19 August, 1876, 3.

- Mason, Jesse D. History of Santa Barbara County, California, with Illustrations and Biographical Sketches of its Prominent Men and Pioneers (Oakland: Thompson & West, 1883).

- WH. Hutchinson to Richard Bard, 12 January 1963, Bard Papers, Research Library, Museum of Ventura County.

- W.H. Hutchinson, Oil, Land and Politics: The California Career of Thomas Robert Bard (Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 1965), Vol. 1, 295.

- Mason, op. cit.

- Padilla, Southern California Gardens. See also David Streatfield, California Gardens: Creating a New Eden (New York: Abbeville Press, 1994), 36-63.

- Charles Saylor, “Bard Garden at Hueneme Has Many Unusual Trees From Over 20 Far Lands, “Ventura County News, undated clipping.

- Ventura Signal, 8 March 1879, 3.

- Ninette Eames, Overland Monthly (1889), as cited in Neal Van Sooy, “The Vantage Point,” Santa Paula Chronicle, 28 July 1948.

- Cephas Bard to Thomas Bard, 1871, as cited in Reaves, op. cit., 28.

- Thomas R. Bard, “The Berylwood Garden.” Unpublished manuscript, n.d., Bard Papers, Santa Barbara Botanic Garden Library.

- Eames, op. cit.

- Bard Papers, 1891-1960, Box 3, Santa Barbara Botanic Garden Library.

- Ibid.

- Carl Wolf, “Taxonomic and Distributional Studies of the New World Cypresses,” in “The New World Cypresses,” El Aliso, Vol. 1. (1948): 176. According to Wolf, Franceschi collected seeds of Cupressus guadalupensis from Guadalupe Island off the coast of Baja California during the winter of 1892-93. See also Carl Wolf, “Horticultural Studies and Experiments on the New World Cypresses,” in “The New World Cypresses,” op. cit., 389. Seeds of this tree had been collected and sent to Europe and California as early as 1880, which would have allowed Bard to order them from a German nursery a decade later. My thanks to Steve Junak at the Santa Barbara Botanic Garden for providing these articles.

- Letter to C.F. Saunders, 12 January 1914, Charles Francis Saunders Papers, 1859-1941, Santa Barbara Botanic Garden Library.

- Thomas R. Bard to Mollie Bard, 12 February 1899. Courtesy of Georgia Pulos and Joanna Bard Newton.

- Thomas R. Bard, op. cit.

- Pamela Coote, “Wilderness,” Oxford Companion to Gardens (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1968), 603-4.

- Architectural historian Robert Winter describes “the ambivalence in [Hunt’s] mind between Arts and Crafts and Beaux-Arts ideals …. ” “Hunt always had an inclination toward classicism ….He would usually side with the elegances of the period revivals as he did with his rich clients, but he found that his early affair with simplicity dominated his work.” Robert Winter, “Myron Hunt and California Culture,” in Alson Clark, ed., Myron Hunt 1868-1952: The Search for a Regional Architecture (Los Angeles: Hennessey & Ingalls, 1984), 75, 77.

- 27 Myron Hunt to Thomas Bard, 14 January 1912, quoted in Shannon Davis, Historic American Buildings Survey, Berylwood Historic District, 2012.

- Peter Barnhardt to Mary Bard, 15 June 1923, Bard Papers, Box 1, Santa Barbara Botanic Garden Library.

- Eric Walther to Mary Bard, 14 September 1936, Bard Papers, Box 1, Santa Barbara Botanic Garden Library.

- Peter Barnhardt to Mary Bard, 19 May 1928, Bard Papers, Box 1, Santa Barbara Botanic Garden Library.

- Katherine Jones, “Vines for California?,” National Horticultural Magazine, Vol. 16 (1) January 1937): 6.

- Peter Barnhardt to Mary Bard, 26 February 1920, Bard Papers, Box 1, Santa Barbara Botanic Garden Library.

- Alice Eastwood to Florence Bolton, 29 April 1924, Bard Papers, Box 1, Santa Barbara Botanic Garden Library.

- Ibid.

- Beryl Bard to Maunsell Van Rensselaer, 5 September 1947, Institutional Archives, Santa Barbara Botanic Garden Library.

- Ralph Hoffmann, “The Herbaria,” Leaflets of the Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History, December 1927.

- A.W. Smith to Katherine Bashford, 16 April 1931, Bard Papers, Box 1, Santa Barbara Botanic Garden Library.

- Richard Bard to Bureau of Nursery Services, California State Department of Agriculture, 6 November 1933; Bard Papers, Box 1, Santa Barbara Botanic Garden Library.

- A.W. Smith to Mrs. E.L. Doheny, 2 February 1932, Bard Papers, Box 1, Santa Barbara Botanic Garden Library.

- Op. cit.

- A.W. Smith to John Merriman, 26 May 1932, Bard Papers, Box 1, Santa Barbara Botanic Garden Library.

- Richard Bard to A.W. Smith, 2 October 1933, Bard Papers, Box 1, Santa Barbara Botanic Garden Library.

- A.W. Smith to Richard Bard, 28 September 1933, Bard Papers, Box 1, Santa Barbara Botanic Garden.

- Beryl Bard to Maunsell Van Rensselaer, 5 September 1947, Institutional Archives, Santa Barbara Botanic Garden Library.

- “Inventory of Trees, Bard Estate, Naval Construction Battalion Center Port Hueneme, California.” Unpublished report prepared by NAVFACENGCOM West Staff Conservationist, 1972.

- Tree inventory conducted by Laurie Hannah, Kevin Knight, and Georgia Pulos, fall 2003.