Joe Terry is interviewed by Wallace E. Smith

Edited with additions from Alvin F. Aggen and others

In this short article from 1980 Joe Terry, a Ventura County farmer, is interviewed on how mechanization changed lima bean threshing in the county. Lima beans were once a major agricultural export in the county. Terry’s recollections offer a snapshot of the social world of agricultural laborers, including a brief mention of Native American workers that creates more questions than it answers. It also highlights the ways in which technological change and automation of physical labor is not a new issue. Terry’s memories show that while new technologies can save time, they just as often have kinks that need to be worked out. As technology changes, it can also create a need for specialized skills. Footnotes are those of the original author unless otherwise stated. The article is from Volume 25, Issue 3 (Spring 1980).

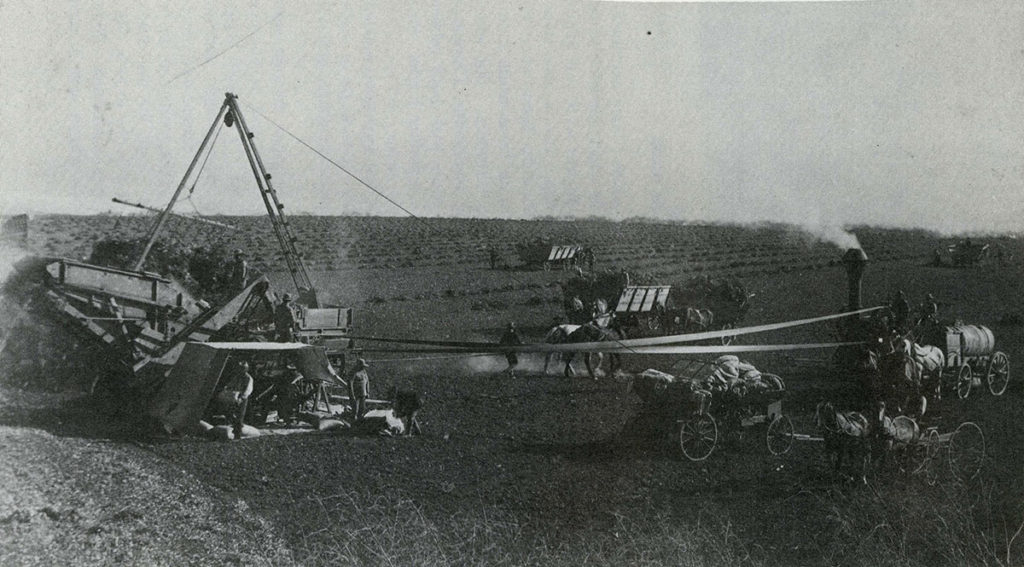

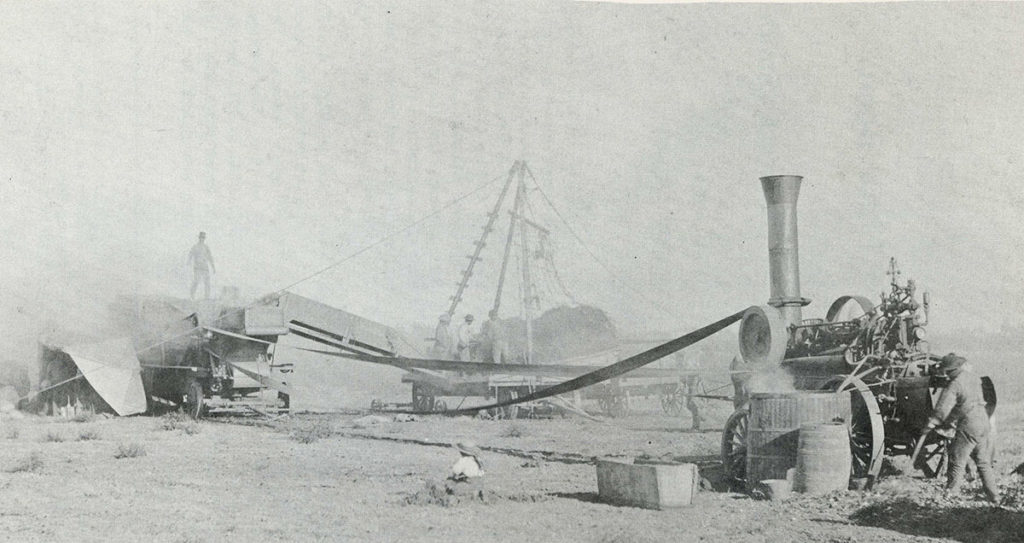

FIFTY-TWO MEN, 38 horses, 14 wagons and a steam engine were needed to keep Jim Kelly’s huge lima bean separator 1 running without a letup in the early days of one of Ventura County’s most important and lucrative businesses. Kelly, a blacksmith, and machinist here before the turn of the century, built a number of these machines in the Nineties2 The Terry separator was built in 1890 for James Ward, Marion Cannon and Charles E. Cook, farmers in the Mound area between Ventura and what was then the town of Montalvo. Their early-day agricultural partnership for the mechanical threshing of beans used a building and lot of Cook’s to store the machinery. The monster was 15 feet high, 12 feet wide and 40 feet long.

Joe Terry bought this bean separator from Cook in 1925. For 37 years he put it to use on his own land near Somis, on acreage he leased in various areas and on bean fields owned by other farmers. The Terrys, father and son, came to Ventura County in 1906. The younger man farmed on his own in Orange County from 1914 to 1919 but returned to join the home operation on Aggen Road seven years before his father’s death. Since his retirement, a third Terry, also named Joe, has farmed the property.

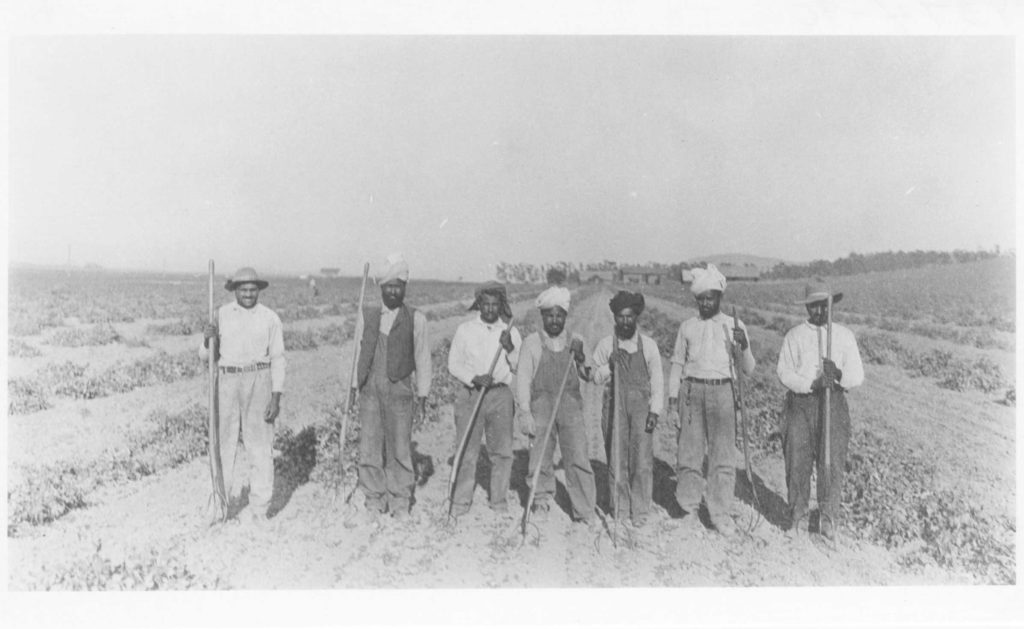

“Dad used to hire Pala Indians as his crew,” Joe Jr. remembered. “He’d turn them loose in Oxnard every Saturday night. Some of the finest people I ever knew.” He recalls one in particular, Richard Attache who once played football at Carlisle with the great athlete Jim Thorpe. But not all of the Terry crew were Indians. 3 4

“Men who followed the harvests would show up for the bean harvest and in 30 to 40 days the crop would be sacked,” the elder Terry said. “Then they’d leave for some other crop harvest. It was no trouble at all to round up a crew. We’d just drive out to where they lived, sometimes in a lean-to under the gum trees, and recruit a crew in short order.” 5

A dollar and a half a day and board would hire a man to drive one of the 14 wagons, Terry remembers. The wagons would haul a continuous supply of cut bean vines to the thresher, which was attached to a moveable steam engine by a heavy leather belt between 60 and 70 feet long. The vines were dumped onto a platform on one side of the thresher. Beans came out the other side and the chaff was blown out through a long moveable funnel at the rear. Two wagons were kept busy hauling the chaff away. This could be baled and sold for cow feed, but it was fuel if the engine was a hay burner.

Crewmen were nearly always experienced adults, Terry explained. Younger men could handle the teams. Wagons in which the bean vines were hauled to the thresher were 16 feet long, 10 feet wide just above the wheel rims and flared out to 16 feet at the top. The wagons came with the separator to the threshing site, furnished by Terry when he contracted to do the job. Various Ventura County firms made them. They had metal rims, and so did Kelly’s huge threshers. But when Terry brought home his separator, a Hueneme blacksmith, Cleveland Wiltfong, overhauled it and replaced the metal rims with hard rubber tires. Wiltfong served for many years as Terry’s separator tender, running the machine and keeping it in good running order.

Two-horse teams moved most of the wagons, but four were needed on the water wagon because of the extra weight. It took six or eight horses to pull the thresher into position (even more on rough ground) because it weighed from eight to 10 tons.

When Terry acquired the bean separator, Caterpillar tractors were just coming into widespread use. “I was about the first in Ventura County to use a Cat on a bean thresher,” Terry said. “I threshed beans in Ventura across Thompson from where Sears now stands, also in Camarillo and Hueneme and other communities. We carried our chuck wagon with us and set it up and went to work.”

The man who drove the water wagon to the threshing site then went back for the chuck wagon. His cook, whose first name was Fred, had a flunky 7 to help him. He had to be on the threshing site before the men awakened. They were bedded down in the straw piles. The chuck wagon was 30 feet long, with benches inside where the men ate.

The crew could seldom start hauling in the beans until 8:00 a.m., and sometimes they had to wait until noon for the vines to be dry enough to harvest the beans. “We usually threshed beans till eight at night,” Terry said. “The men who pitched the vines into the separator would take lanterns from the chuck wagon’s storage box and hang them on their wagons until they were loaded; and we’d hang a lantern on the separator so they could find us again in the dark.”

There was no daylight saving[s] time in those days. Even in the summer months, it would

grow dark before 8:00 o’clock. It took more hand labor to harvest beans on the hillsides; but they could be grown anywhere the ground could be plowed. Irrigation was no problem since beans were dry farmed.

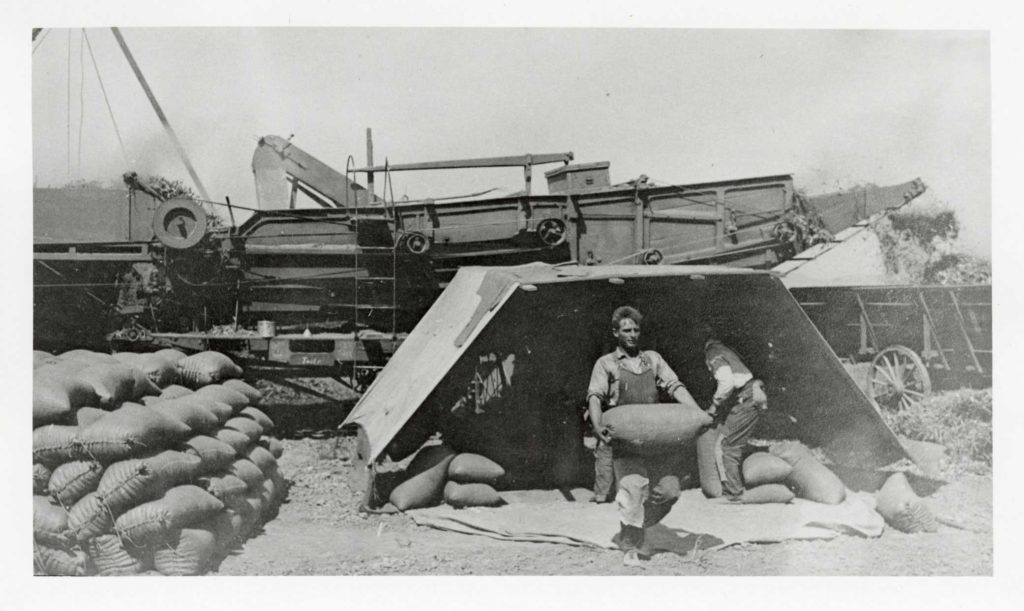

The beans emerged into a small, sheltered area known as the “doghouse,” where four men worked at top speed. One filled the bean sacks and the other three sewed them shut.8 “That’s where the action was,” Terry said. “Those men could handle 1,500 to 2,500 sacks a day.”

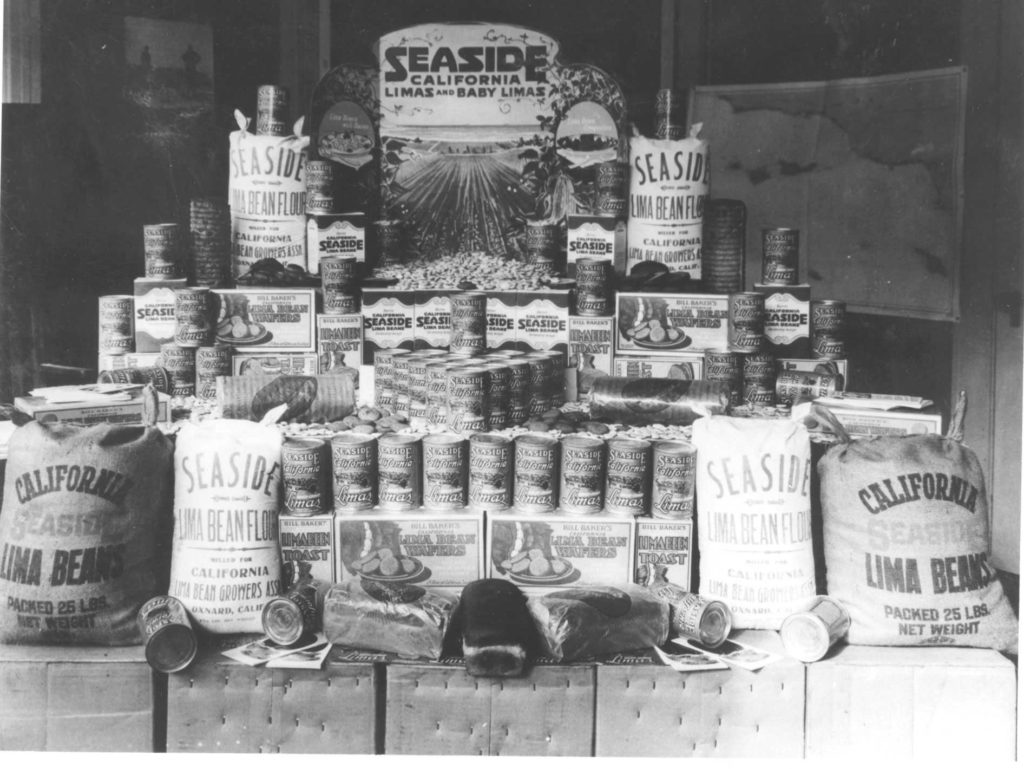

The sacked beans were then hauled off to be stored for marketing at the nearest Southern Pacific Milling Co. warehouse in Somis. The company had storage facilities also in Moorpark, Santa Susana, Camarillo, El Rio, Oxnard, Ventura9, Montalvo10, Saticoy, Santa Paula, and Fillmore.

Eighty-pound sacks were used at first; later on 100-pound. The huge threshers were shared: “You couldn’t afford to have all that equipment for just one farm,” Terry pointed out. “I’ve threshed beans clear into November.” Terry believed he could harvest 10-25 sacks of beans to the acre without irrigation and without fertilizer, both of which have long since sharply increased the yield per acre. Terry recalls that he was paid 25 cents a hundredweight for threshing and sacking limas on other farmer’s land, furnishing the men, horses and wagons, and the food for the crew. The farmer whose beans were being threshed would supply feed for the 38 horses and wood for the chuck wagon range. Whenever it rained, which was infrequent during the summer months, Terry had to pull his crew off the job until the vines dried out enough to resume threshing. It was an expensive happenstance. “We still had to feed all those men,” Terry said.

In the old days between 50,000 and 60,000 acres of Ventura County land were planted to beans each May, harvested usually in September. Some yields were as high as 50 sacks to the acre. But preparations for the harvest began in the fields of the farmers: vines to be cut, gathered and the piles turned after two weeks to dry the pods underneath.11

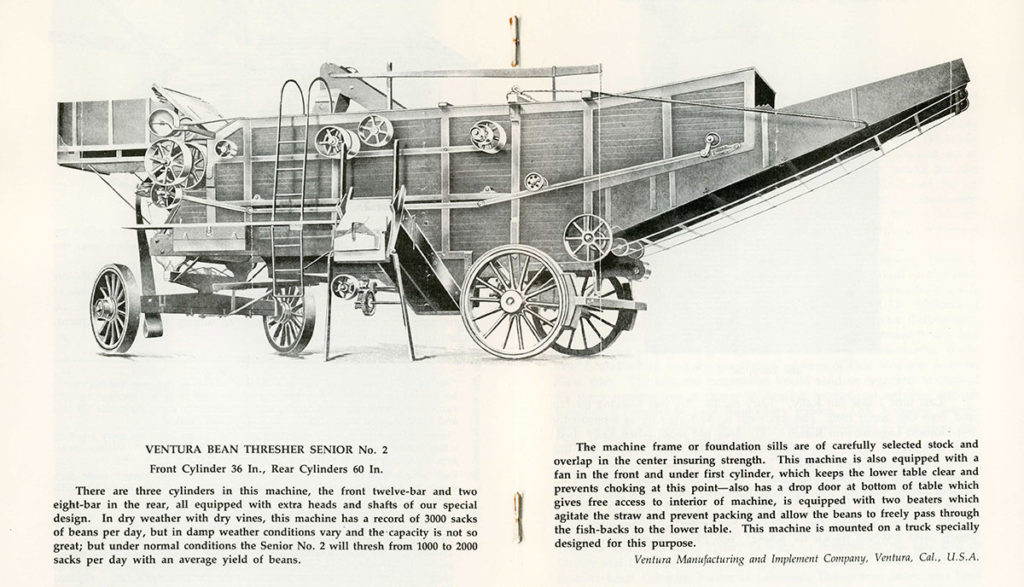

When the East Winds swept through the beanfields, the vines rolled up into long cylinders, which made them more difficult to pitch into the wagons.12 Kelly built many of the separators; but William Hamilton, a Hoosier machinist who lived on Harrison Avenue in Ventura, made a number of the huge machines for Ventura Manufacturing & Implement Co. on Front Street.13 Hamilton was minus two fingers from his left hand, [a] victim of a machine shop accident.

“Last time I saw Jim Kelly,” Terry recalls, “he was working for Jim and Tom Gill about 1940. His son went up to King City as foreman for the Hobson-Lagomarsino Ranch.” He does not recall when Kelly died. “He was an old man when I first knew him in 1925,” Terry said.

But there were many others threshing beans. Jim Gill had two sons, and all three threshed both grain and beans. Robert Lefever can remember an Angelo Milani working with him and his father, Supervisor Bob Lefever. H.R. (Rich) Jewett was the machinist for Walter Duval and the McGraths. Dick Lunsford can recognize his father in a threshing crew which used a wheel tractor for power. Bob Pfeiler recalls John Dawley and Enoch Waters.

- A thresher only knocked out the beans and did nothing else; dividing the chaff and delivering clean beans as well was the function of a separator. This mechanization replaced the flail and the threshing floor. Hard ground and horses were still used for seed beans up to 1920 in the Tri-County area.

- Editor’s note: The author means the 1890s.

- Editor’s note: The Pala Band of Mission Indians government is located on the Pala Indian Reservation in San Diego County. It’s not clear if Joe Jr. is correct in referring to the Pala people or if he was mistaken. The phrasing “turn them loose” also raises questions regarding labor practices and how restricted the movement of these Indigenous laborers was.

- Chief Ortega operated the separator for Urban Underwood who threshed the Cannon property, among others. He was a good machinist himself and modernized his separator with ball bearings. Ortega was a graduate of the Sherman Indian Institute at Riverside, and wrestled (which may account for his title) in his spare time; he was known for his pugnacious disposition.

- Editor’s note: The original footnote indicated that the phrase “hobo jungles” was used to refer to settlements that were home to transient workers who were often hired for farm work.

- This photo is from the MVC’s Research Library. Terry’s original narrative does not mention South Asian workers. The photo was chosen so that readers could see that Ventura County’s workforce may have been more diverse than is often assumed and to highlight people who are often not included in certain narratives.

- Editor’s note: A flunky is a demeaning term used to refer to someone who does menial tasks.

- Only two sewed at one time; the other took his turn.

- Bought later by Ernie Pate for a seed warehouse, it burned down on March 19, 1974.

- [1] “In 1889 the Southern Pacific Milling Company erected a large warehouse, 120 feet long, near the railroad tracks. In 1890 this was found to be inadequate, and 100 feet [more] were added. In 1892 another 100-foot extension was made to accommodate the accumulating bean products. So, in 1892 the warehouse was 420 ft. long and 50 ft. wide. Every year this was filled to overflowing.” Lena (Cannon) Walker, Montalvo P.T.A., Feb. 5, 1953.

- “When the pods turn yellow (before they dry out) the vines are cut just below the surface of the ground. This cutting is done, two rows at a time by a bean cutter. The runners of the sled are sufficiently wide apart to take in two rows and the fingers and the knives are set toward the center. By this arrangement the vines, as cut, are forced into a wind row in the center. The runners are made of selected Oregon pine and are iron shod, the fingers of ¾ inch pipe iron; the knives are made of knife steel and are six feet long. It is provided with a handlebar for shifting. Team required is three horses. An improvement can be made by adding wheels to the rear: the blades can be leveled by raising or lowering them; the draft is lighter because the sled runners are not so long; in turning at the ends of the rows, they raise the sled and avoid accumulating dirt on the ends of the runners. Immediately after cutting, the vines are forked into piles, six rows together; when thoroughly dried, they can be hauled to the thresher.” Ventura Manufacturing and Implement Company, Ventura, Cal. U.S.A.

- Each wagon was provided with a strong rope net. The derrick could then dump the load onto a portable platform; and the vines were pitched into the feeder.

- Ventura Manufacturing & Implement Co., Front St. between Laurel and Ann Sts., Ventura, Calif. was incorporated in 1903 and liquidated on March 16, 1939. William Hamilton was its longtime superintendent and manager. Its catalogs include bean separators which, like others here, were adapted from a midwestern model, the wheat thresher. The minutes of its directors’ meetings show that Jim Kelly was associated with the company for a time. Winfield Scott Saviers split the profits on his discoveries with it. He invented a separator which would thresh lima beans, small beans, barley, wheat, and oats.