by Library Docent Volunteer Andy Ludlum

It was a quiet June morning in 1926 when Joshua Stockton of South Mountain set out along the trail to his ranch. Just beyond a sharp bend, a shadow leaped from the chaparral and a mountain lion blocked his path. For a heart-stopping moment, man and beast stared each other down. The lion lunged, closing to just ten feet, its wild eyes fixed on Stockton. Most would have run but Stockton held his ground, slowly moving forward, refusing to give an inch. Then, as suddenly as it appeared, the predator froze, spun on its haunches, and melted back into the brush, leaving Stockton shaken, awed, and unharmed. “It must have had young in the brush,” he later said, “and was just trying to scare me off.” This close call reflects the uneasy history of people and mountain lions in Ventura County. For thousands of years, they’ve shared the land, but over the past 175 years, as ranches, towns, and cities spread, the shrinking wild left little room for coexistence, often with deadly results for the lions.

The First Fierce Encounters

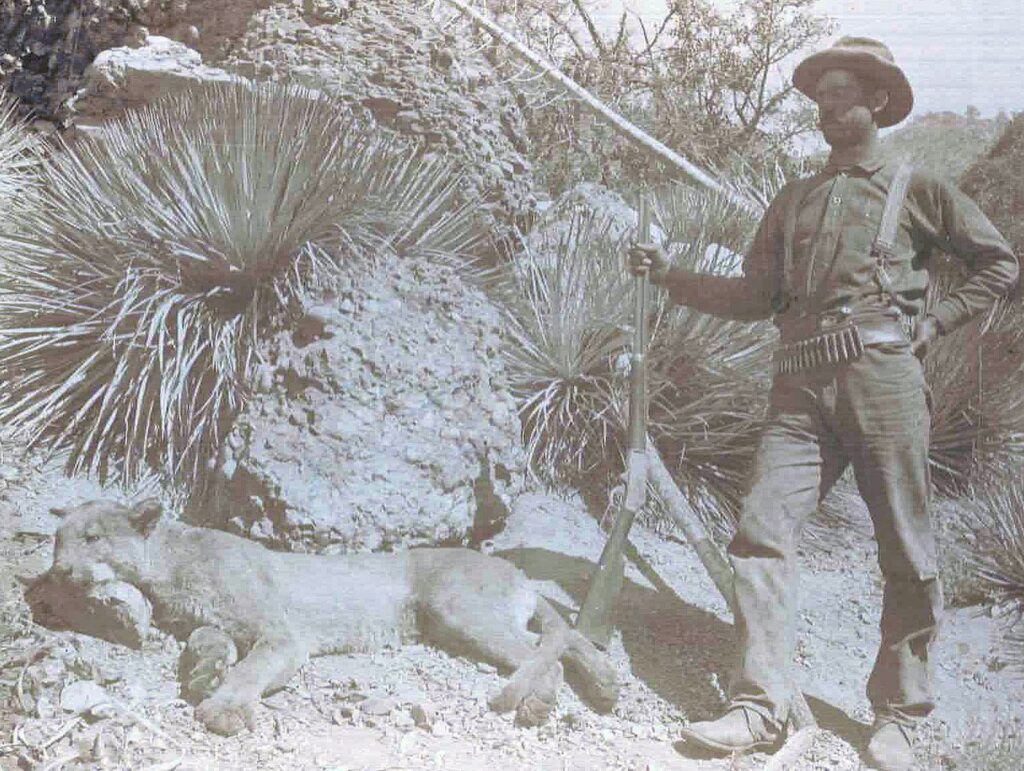

When settlers built their farms and ranches in Ventura County, they moved into mountain lion territory. To ranchers, lions weren’t creatures to respect but dangerous pests that threatened their animals and their way of life. Some of the earliest tales, colorful but impossible to fact-check today, describe fierce and almost unbelievable clashes with mountain lions in Ventura County. In 1876, Ojai newspaperman T. S. Newby recalled strumming his guitar under a tree when a lion appeared above him, tail twitching as if ready to strike. For hours he and the animal stared each other down until a violent struggle broke out. With his dog Chappo’s help, Newby claimed he finally killed the lion in a bloody, hand-to-hand fight. A few years later, in 1881, fourteen-year-old Fred Ortega of Ojai was credited with killing a nine-foot lion that had been raiding his family’s calves. After dogs treed the cat, Ortega missed with his pistol but managed to rope it with a riata and finish it off with a club, earning him local fame as a boy hero. In 1882, two teenage sisters, Belle and Sarah Lyon showed courage when their dogs chased a lion up a tree on their family’s Matilija ranch. Sarah ran for help while Belle stood guard with a shotgun. She wounded the animal twice before a neighbor arrived with a rifle to finish the job. Local newspapers eagerly published accounts of ranchers killing the predators and showing off their trophies. In 1887, The Ventura Weekly Post and Democrat predicted the campaign against mountain lions was so successful “they would soon be extinct.” The paper remarked that while their disappearance was “no tragedy,” the lions had provided “interesting stories.” In 1886, hunter Mart Beekman proudly displayed the skin of an eight-foot lion his dogs had treed, telling the Ventura Free Press it took three revolver shots to bring the animal down. In 1893 a lion in the Matilija killed two colts before being shot, its massive head was hauled into town, where reporters marveled at the teeth and jaws, remarking, “no wonder they are tough customers to have anything to do with.” That same month, another lion raided G. O. Taylor’s chicken house near Ojai, devouring a dozen birds and nearly escaping with a dog before Taylor beat it back, breaking his gun over the animal’s head. In other cases, poison replaced bullets. After a lion killed a horse near the Sespe, ranchers baited the carcass, and when the predator returned, it “surrendered to the inevitable.”

Fascination, Myth, and Opportunity

Because mountain lions are so elusive, most people never saw one. Oral histories at the Museum of Ventura County reflect this. Dale King, Sr., who had lived in wilder parts of the county since the late 1800s, admitted he never clearly saw a lion. He heard their cries, found their kills, and once thought he spotted two, but he could never be certain. Others remembered only brief glimpses. William Miller of Somis recalled seeing a lion in his lemon orchard. He downplayed the moment, though the interviewer noted how unusual it was. Miller agreed, noting that people rarely saw lions, even when they lived close by. The newspapers viewed mountain lions with a mix of fascination, myth, and opportunity. The Ventura Weekly Post and Democrat promoted Ventura County as a sportsman’s paradise. Besides deer and small game, visiting sportsmen “seeking a true test of skill” could venture into the nearby mountains and pursue the “ultimate trophy,” a mountain lion. The articles often exaggerated the mountain lion’s size and danger. In 1887, The Ventura Weekly Post and Democrat reprinted a story from the Philadelphia Times claiming lions measured ten to twelve feet long and weighed up to three hundred pounds. Mountain lions are much smaller. Males can grow just over eight feet long, while females are more commonly around seven feet. Males usually weigh 130 to 150 pounds, and females 65 to 90 pounds. Sometimes the stories were more amusing than frightening. In 1892, the Ventura Free Press reported a rancher in Stewart Canyon was hunting a lion that was “troubling his bean crop,” even though mountain lions don’t eat beans, or anything plant based. They are strict carnivores and survive on meat, mostly deer. It was this appetite for deer that led the state to put a price on the mountain lion’s head in 1907.

The State-Sanctioned War on Lions

In 1907, California offered a $20 bounty for every mountain lion scalp turned in by hunters. The State Fish and Game Commission justified the policy, calling the mountain lion a “fierce and untamable varmint” that killed livestock and, most importantly, deer. In Ventura County the newspapers noted that a determined hunter could make steady money pursuing them. Reports claimed that about 40 lion scalps a month were being submitted statewide, with the commission paying out thousands of dollars. Game wardens argued that each lion killed one to three deer a week, meaning their removal could “save” as many as 25,000 deer each year. The Ventura Free Press declared in 1908 that placing a bounty on mountain lions was “one of the greatest of the deer-preserving movements” ever undertaken. Between 1906 and 1963, approximately 12,580 mountain lions were killed under this program.

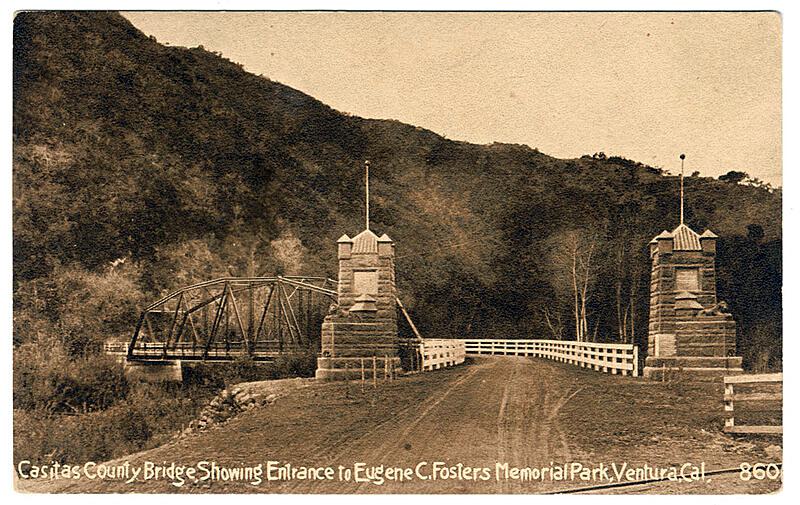

In September 1908, a huge mountain lion appeared in Ventura’s newly established Foster Park. Angelo Tassano, a young Italian man working for his brother, a Los Angeles florist, was confronted by the lion when his dogs treed it. Armed only with a single-barrel shotgun loaded with small buckshot, Tassano fired several rounds at the lion as it leapt from limb to limb, barely keeping it at bay. One of his dogs was badly injured in the struggle, and Tassano only managed to bring the lion down after a tense, close-range confrontation. The Ventura Morning Free Press, in its first story on the incident, suggested that Tassano had been collecting ferns in the park for his brother when he stumbled upon the lion. The story implied he was trespassing or exploiting the park’s resources. Tassano strongly protested the claim, issuing an emotional public statement denying that he had been hunting ferns for profit and that the encounter with the mountain lion was entirely unexpected. Tassano demanded that the record be set straight, insisting he deserved recognition for his bravery, not suspicion of wrongdoing. The lion was brought into town, weighed, and measured. Buckhorn Club owner Phares Meyers bought the lion from Tassano, who had considered having it mounted or made into a rug, but agreed to sell when offered gold. The lion was stuffed by a taxidermist and added to the Ventura club’s collection of mounted deer horns, animal heads, and rattlesnake skins.

Not every confrontation ended violently. In 1913, while walking along the Pratt Trail from Wheeler’s Springs to Ventura, Neil Love suddenly came face-to-face with a large mountain lion blocking the path. At first, he tried backing away and shooing the beast, but it wouldn’t budge. Thinking quickly, Love pulled out his harmonica and began to play, running through a lively tune. The Oxnard Courier reported, amazingly, the lion paused, then turned and darted into the brush, either frightened or strangely charmed by the music. In another story, Mrs. Ayers, a Ventura woman who found a lion in her chicken yard, drove it off by simply shaking her apron at it.

Mountain lions were increasingly portrayed as a threat to California’s deer herds. In 1913, The Ventura Weekly Post and Democrat reported that about 30,000 deer were dying each year, 10,000 to hunters and the rest to predators. Game officials claimed each lion killed about 52 deer annually. Hunters and ranchers never passed on the opportunity to shoot at mountain lions. In 1909, the Morning Free Press reported a fierce encounter near Wheeler’s Springs in Sespe Canyon, where men killed a lion nearly eight feet long. Just after the shot rang out, a cow came charging down the trail, still frantic from fighting off the predator. Tracks revealed the lion had attacked her newborn calf. The mother had bravely defended it, but the calf did not survive.

Five years later, The Ventura Weekly Post and Democrat described John Hitchcock’s brush with one of the largest lions ever seen in the county. Living in the remote Santa Ana district, Hitchcock was used to predators, but this lion had been raiding farms, stealing pigs, goats, and calves. One night, hearing squeals from his neighbor Juan Valencia’s pigs, he grabbed his gun and spotted the lion clearing a fence. He fired, wounding it, but the animal escaped, shrieking into the hills. “Only a fool would follow up a lion that had his skin full of number six shot,” Hitchcock admitted. Instead, he baited a steel trap with a young goat, vowing, “We’ll get the old cuss yet.”

Not all lion hunts ended as planned. In 1915, Herbert Lathrop, owner of a remote Sespe resort, was accidentally shot and killed when hunter mistook him for a lion. Lathrop was working on a hillside near his cabin when he was struck in the abdomen by a bullet fired by Madison Perritt. At the inquest, Perritt wept as he described the mistake: he had seen movement in the brush, took aim, and fired—only to hear Lathrop cry out, “Oh my God.” Lathrop died before help arrived, but not before forgiving Perritt. The jury ruled the shooting accidental.

Deputy Fish and Game Commissioner Jack Barnett was a leading figure in the push to eradicate mountain lions in Ventura County. In 1918, he organized a “grand clean-up” hunt, even attracting a Los Angeles film crew to capture the effort. By 1919, Barnett brought in the legendary hunter “Jerky” Johnson, known for record-breaking lion kills, along with his traps and dogs. More hunters soon followed. In January 1920, five highly trained bloodhounds and their hired hunter/handlers arrived in Ventura to track two lions near the Selby ranch. The war on lions wasn’t limited to professionals. In 1920, Mrs. Roland Gray of the upper Ojai Valley offered her own $15 bounty for a lion troubling her area, on top of the state’s reward.

Upping the Ante: The Push for County Bounties

The pressure to eliminate mountain lions was relentless. By 1921, official records showed that 40 lions were killed in Ventura County between 1907 and 1917, with two more in 1918 and two in 1919. In June 1921, the Oxnard Press-Courier reprinted an article by J. S. Hunter from the California Fish and Game Commission’s magazine. Hunter argued that mountain lions were the most destructive predators in California. By January 1920, the state had paid out $65,550 in bounties for lions. The reward for killing a female lion was raised from $20 to $30 in 1917, and between then and 1920, 218 females were turned in. Hunter estimated California’s lion population at about 575 animals.

Game Warden Barnett became increasingly vocal about the idea of Ventura County having its own bounty to add to the state bounty on mountain lions. In 1922 he urged a $50 bounty on each lion, half funded by the county, half by the Cattlemen’s Association. Barnett hoped neighboring Santa Barbara and Los Angeles counties would join the effort. The Ventura Weekly Post and Democrat editorialized that mountain lions “are no respecter of does or fawns” and warned that preserving the deer population required controlling the predators. The paper supported Barnett’s proposal, adding that sportsmen, who suffered from lion predation on game, could also contribute.

By November 1922, the Morning Free Press reported that the State Fish and Game Commission reinforced the call for additional bounties. The commission had long paid $20 for a male and $30 for a female lion, but officials noted that higher bounties were needed to attract skilled hunters capable of tracking and exterminating lions. Santa Barbara County had already added $50 to the state bounty. The commission emphasized that hunting lions was challenging work, often pursued more for sport and the protection of deer than for money. To reduce the threat posed by mountain lions, the commission hired professional hunter, Jay C. Bruce.

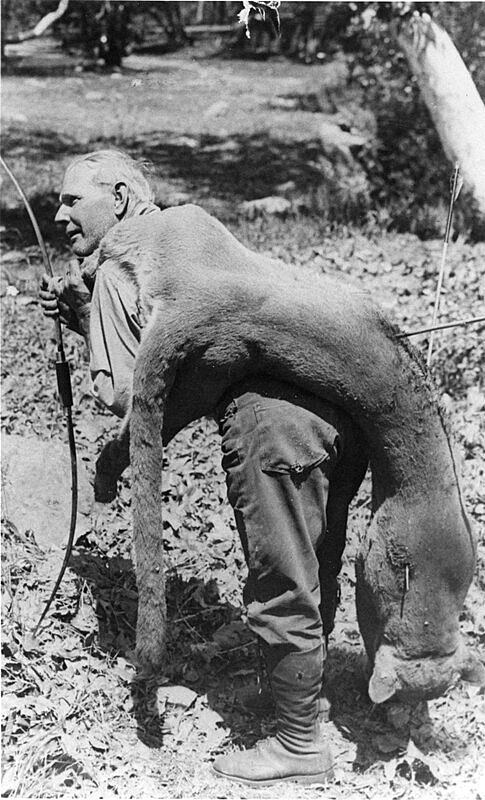

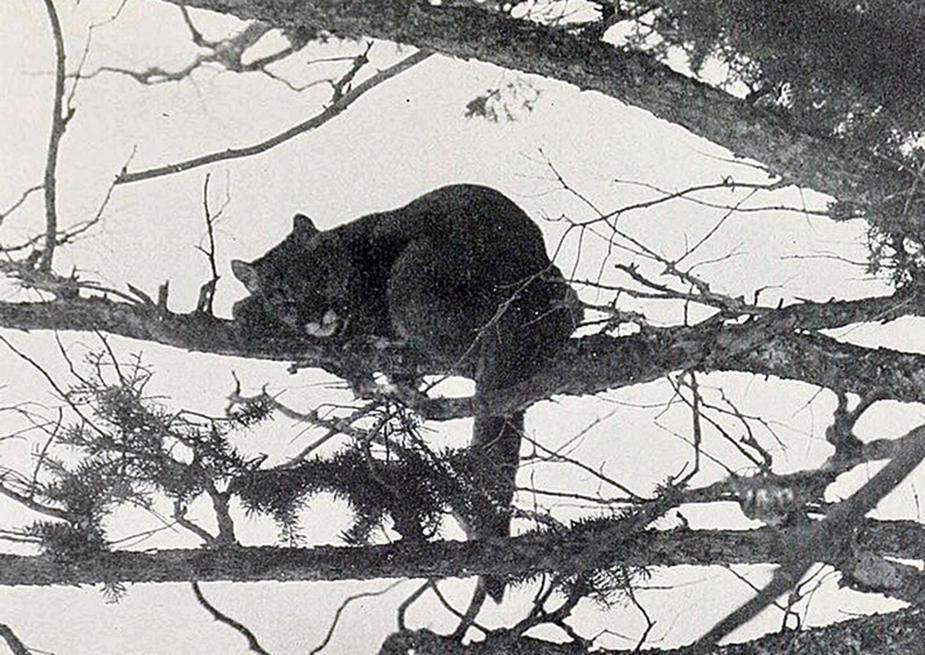

Bruce arrived in Ventura County, already known as one of the nation’s most effective lion hunters. The Ventura Weekly Post and Democrat marveled at his unusual methods, tracking lions with a .32-caliber revolver and a pack of six trained dogs through the rugged Matilija and Sespe backcountry. Bruce often spent months in the hills, and his hunts became local legend. In 1926, the Ventura County Star reported that a large male lion Bruce killed in Cherry Canyon was put on display in a Ventura sporting goods store. By November, the same paper noted 284 notches on Bruce’s rifle stock, marking each lion killed. Bruce defended his work by insisting that mountain lions killed “for fun,” often leaving deer carcasses untouched. Bruce paired hunting with study. According to the Ventura County Star, he examined lion stomach contents, tracked behavior, and sent his findings to the University of California. He was clear that he did not see himself as a mere “slaughterer,” and blamed “sentimentalists” who, in his view, misunderstood lion behavior. In 1931 the Ventura County Star reported Bruce had killed over 400 lions since 1919.

Game Warden Barnett’s push for a county bounty on mountain lions became reality in 1930. The Ventura County Star reported that Tom Harrison and Herman Keene of Santa Paula urged supervisors to pay hunters for killing lions. They estimated 15 to 20 lions lived in the county, each taking about 50 deer a year, and argued the statewide loss of venison was worth $40,000 annually. Supervisors agreed and promised a $20 bounty in the next budget. Five years later, the Ventura County Star noted that Supervisor Tom Clark of Ojai was working with nearby counties to set a uniform bounty, since Santa Barbara’s $50 rate was higher than others. Soon after, the Morning Free Press reported Ventura County raised its own bounty to $50, more than doubling the original reward.

The Evolution of a Lion Hunter

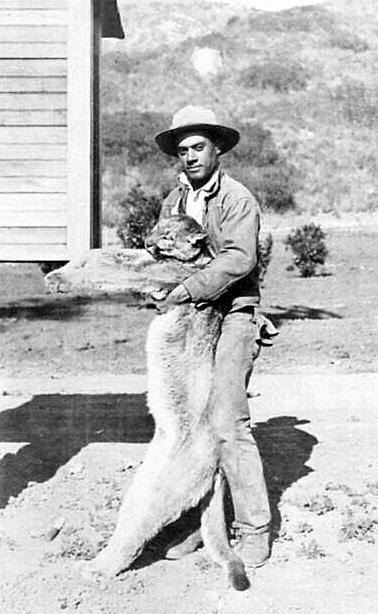

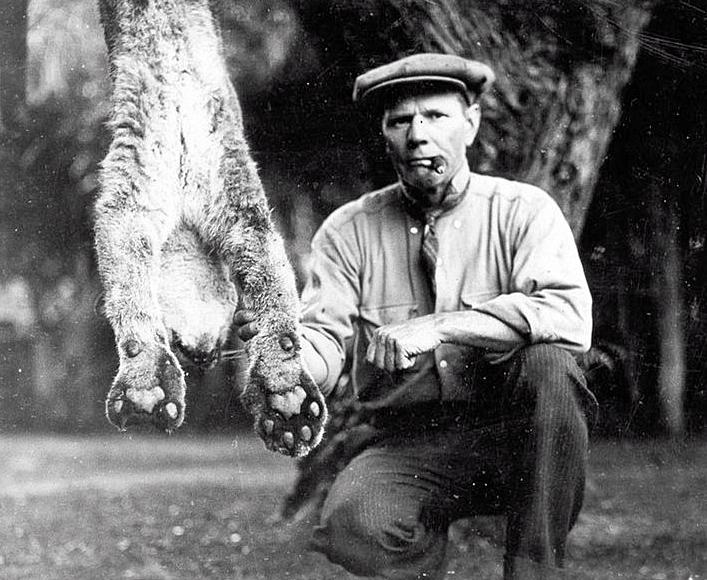

Herman Keene, who testified before the Supervisors, was Ventura County’s most colorful mountain lion hunter. For more than half a century he trapped the county’s rugged backcountry, tallying 40 lions by his own count, yet he admitted late in life: “I’ve never seen a loose mountain lion… only in traps or chased by hounds.” In 1933, displaying his knack as a showman, Keene killed a 125-pound lion with a bow and arrow while a teenage boy filmed the feat for posterity. He once captured a full-grown female for the Oxnard Lions Club, only to see it die days later at Goebel’s Lion Farm, destined to be mounted. He posed proudly for photographs, often with a dead or caged lions at his feet, and entertained crowds at schools and service clubs with motion pictures of himself battling “California’s public enemy No. 1.” Twenty of Keene’s movies are in the Museum of Ventura County’s collection. He also had a knack for quotable lines. He declared the mountain lion “an abject coward, except when in the trap.” At other times he called them “California’s worst killer.” And yet, as the years went on, his tone softened. In 1933 he estimated only about 450 lions remained in California and argued that they served a role, weeding out diseased deer. The man who once bragged about killing with bow, bullet, or trap came to call himself more a naturalist than a hunter.

Keene’s relationship with Ventura County Star editor Joe Paul Jr. helped burnish his legend. Paul was unabashedly a fan, devoting whole “Looking at Ventura County” columns to Keene’s exploits. Paul cast the hunts as epics, praising Keene’s endurance, trudging through waist-deep snow at seventy years old, and his almost mythical rivalry with the last great cats of the backcountry. By the time of his later interviews, Keene openly acknowledged the paradox of his life. He had made his name killing or capturing lions, yet he insisted they were almost never seen and rarely a danger to people: “The chances of seeing a wild mountain lion are about ten million to one,” he said in 1954.

From Squeaky to Kimbo: The Debate Over Wild Pets

Over the decades, Ventura County residents encountered mountain lions kept as pets. Some accounts recall them as tame companions, while others ended in danger or tragedy. In 1927, a Ventura parking garage attendant reached through a car window and found himself stroking the fur of a lion calmly waiting for its owner after a movie audition. Other Hollywood encounters proved more dangerous: in 1949, a producer was mauled on set when a lion broke its leash, and in 1953 a trainer was clawed during a show when a spooked lion lashed out. Not all stories were grim. Fillmore teenager Mary Lynn Bice briefly raised a bottle-fed cub named Squeaky in 1950, turning him into a local celebrity before he grew too big. The risks, however, were always there. In September 1957, 12-year-old Albert Lee was mauled while playing hide-and-seek in Newbury Park by a pet lion named Kimbo who had gotten out of his backyard cage. Lee’s father and uncle pulled the 150-pound animal off with their bare hands before shooting it. Lee survived, but the attack shocked the county. Public debate followed. Some demanded strict controls, others defended the right to keep wild pets. After months of wrangling, supervisors passed Ventura County’s first wild animal ordinance in 1958, which made it illegal for a wild animal to be outside of its cage without a handler.

A Shift in How People Saw Mountain Lions

In the 1950s, public opinion about mountain lions began to change. Instead of seeing them only as threats to deer and livestock, people started to recognize their role in the ecosystem. Richard Borden, director of the National Wildlife Federation, urged the public to view predators as a natural part of the environment. At a 1950 hearing on creating a 40,000-acre California condor refuge in the Los Padres National Forest, officials noted that food for the endangered birds was running short. In the past, mountain lions had provided carrion by killing deer, but by then the lions were nearly gone from the region. Without a steady food supply, they warned, even a large refuge might not be enough to save the condor.

Mountain lions were leaving the wild and appearing more often in towns and neighborhoods. In September 1955, Mrs. Jessie Rhodes of Santa Paula finished work at the Ventura School for Girls and headed to her car, only to find a lion sitting in the back seat. She screamed; the cat bolted through the front window and vanished into the brush. Pranksters played on the public’s lingering fear of mountain lions. In 1954, huge “tracks” appeared on Pierpont Bay beach, but they all came from a single right paw. Local foreman Bob Ellsworth exposed the hoax. Kids had stamped the sand with a fake paw, feeding into a wave of recent false sightings.

Local newspapers in the 1950s captured a shift in how people saw mountain lions. Early coverage stuck to the old predator-versus-rancher theme. One article called the cougar a “colorful wildlife denizen” but still a menace to stockmen. Trappers like Boyd Seguine defended their work by saying once a lion killed cattle, “he becomes a cattle killer for life.” Newspapers still celebrated hunts, reporting on “Lion Derby” contests and bounty totals. By 1959, dissenting voices began to surface. Letters to the editor argued that most lions rarely killed cattle and that removing predators upset the natural balance, leading to more rodents and snakes. Some readers expressed disgust at photos of hunters with their kills, suggesting lions were vital to keeping ecosystems in check. Even ranchers joined in, saying reports of cattle killings were exaggerated and calling hunters the real predators. Outdoor writers soon echoed this view. In November 1959, Outdoor Life columnist Rick Brazil noted that removing lions led to deer overpopulation and starvation and suggested ending the bounty. By January 1961, editor Joe Paul, Jr., who had once praised lion hunters, admitted that lions were no longer the menace they once seemed, though he acknowledged ranchers scarred by earlier losses found it hard to agree.

Mutiny on the Bounty

Discussions that began in December 1960 culminated in the end of bounties for mountain lions, first in Ventura County and then statewide. The county debate began when Supervisor Robert Haley noted that lion populations were diminishing and that Ventura was one of only a handful of California counties still paying a bounty. Supervisor A. C. Ax added that with deer herds growing “to huge proportions… killing off lions may be upsetting nature’s balance.” The conversation intensified after the county discovered hunters were bringing lions killed in other counties to Ventura to collect the bounty. By March 1962, both the Ventura County Farm Bureau and the County Cattlemen’s Association supported dropping the payment. The bounty was officially eliminated later that year.

Momentum then shifted to the state level. An editorial in 1962 called the bounty system a “waste of funds and a biological mistake,” noting that lion populations had fallen to an estimated 600 statewide. Early in 1963, State Senator Fred S. Farr of Carmel introduced a bill to end the state bounty, arguing the animals were disappearing “at an alarming rate.” The legislation gained support from the Department of Fish and Game and even the California Cattlemen’s Association, which agreed to a trial suspension. During a committee hearing, opponents voiced their disapproval. “I don’t know what you nature lovers are thinking about,” argued Senator John C. Begovich, “Twenty years ago… the cowboys of California would have lassoed you right off this committee.” Despite some opposition, the bill passed, establishing a four-year moratorium on the state bounty. By the time the program ended, more than 12,000 mountain lions had been killed for a bounty payment.

A New Status for the Big Cat

In a significant policy shift, the California Legislature in 1969 reclassified the mountain lion from a nonprotected animal to a big game animal, officially placing it under the management of the Department of Fish and Game. The new law meant that for the first time, hunters were required to purchase a $1 license tag before taking a mountain lion. Previously, as a nonprotected species, the big cats could be killed at any time without a permit. The new law also mandated that all kills be reported to the state, though it included an exception for ranchers to kill lions threatening livestock without a tag. The data gathered from the new tag system was intended to help officials determine if formal seasons and limits were needed to keep a stable lion population, then estimated at around 600 lions. The state held two short hunting seasons in 1970 and 1971, during which 118 lions were legally killed.

The Contentious Campaign for Prop 117

By the early 1970s, many Californians were uneasy with the idea of hunting mountain lions for sport. In February 1971, Assemblyman John Dunlap held a dramatic Sacramento press conference, flanked by two live lions, to announce his bill banning lion hunting. Citing the state estimate of only 600 lions, he warned, “We are selling out the mountain lion dirt cheap,” and argued for the principle, “when in doubt, preserve. We can always destroy later.” The proposal sparked passionate public response, with conservationists urging support and hunters and the Department of Fish and Game questioning the numbers.

The original bill for a permanent ban failed, but a compromise created a four-year moratorium beginning after the 1971–72 hunting season. The law required Fish and Game to study mountain lion numbers, sparking debate when the department suggested there could be as many as 2,400 in the state, four times the previous estimate of 600. The moratorium extended beyond four years as competing pressure from both hunters and animal advocates left the Fish and Game Commission paralyzed, unwilling to reopen hunting.

California voters in June 1990 approved Proposition 117, the Wildlife Protection Act, creating a landmark conservation fund and banning the trophy hunting of mountain lions. The contentious campaign pitted environmental groups against ranchers, hunters, and fiscal conservatives. The measure passed with 53 percent of the vote. The initiative created the Habitat Conservation Fund of $30 million a year for 30 years to purchase and preserve wildlife habitat in the state. Its most high-profile element, however, was designating the mountain lion as a “specially protected animal,” ending sport hunting permanently.

Proponents argued that the measure was a vital step to protect the state’s natural heritage from relentless development. They clarified that the funding was not a new tax but would come from existing environmental funds and unallocated tobacco tax revenue set aside by a previous initiative. An editorial in the Thousand Oaks Star endorsed the measure, stating it would “enable the state’s animal and plant life to thrive along with its people.” Opponents such as Newbury Park resident William E. Poole Jr. called the measure “biologically unsound,” arguing that the mountain lion population was healthy and did not need saving. He, along with other critics, claimed the initiative would divert millions from underfunded state programs, including health care for which the tobacco tax was primarily intended. Moorpark Assemblyman Tom McClintock bluntly called the measure “Save the Mountain Lions, Forget the People,” adding that the lion “apparently reminds enough people of their house cat to evoke sympathy at the expense of health programs for human beings.” Despite the initiative’s passage, the reality of its implementation raised immediate concerns. A Ventura County Fish and Game Warden, Ernie Acosta, warned that the new law gave the department “additional responsibilities with no money to deal with the overload.”

The Rollback Fails

Six years after the passage of Proposition 117 opponents tried to roll back the hunting ban with Proposition 197. Supporters cited growing human-lion encounters, including a Fillmore man who watched a lion kill his 75-pound dog, as evidence of danger. Opponents called the measure fearmongering, noting attacks on people were extremely rare. A psychology instructor commenting on the election quipped that if the issue were about killer cockroaches, “we’d just wipe ‘em out.” Voters rejected the measure, 58% to 42%, reaffirming protection, with Newbury Park resident Asia Real declaring, “We voted in 1990 to protect the mountain lion from trophy hunting, and we’ll do the same in 1996.”

Efforts continued to address conflicts between people and lions. In 2014, Senate Bill 132 required officials to use non-lethal methods unless a lion posed immediate danger, and in 2017 the Department of Fish and Wildlife adopted its statewide “Three-Step Policy” prioritizing non-lethal solutions for livestock predation. The biggest shift came in April 2020, when the California Fish and Game Commission granted interim protections under the Endangered Species Act to mountain lions in Southern California and the Central Coast. Researchers warned that habitat loss and freeway isolation had left these populations genetically fragile, and without action, they could face extinction. The protections triggered a year-long review and temporarily treated the lions as fully listed species, affecting development projects. Dozens of public comments supported the move, including those of Ventura County Supervisor Linda Parks, though some ranchers and housing advocates expressed concern over livestock safety and new construction.

No Verified Attacks in Ventura County

Since 1890, California has recorded fewer than 50 confirmed mountain lion attacks on people, only six of them fatal. About 22 documented attacks involving 24 victims have occurred since 1986, but none have been verified in Ventura County. Here, the closest encounters usually involve pets or frightening, but harmless sightings, especially in the Santa Monica Mountains and Los Padres National Forest, where lions still roam near neighborhoods. The chance of being attacked by a mountain lion remains virtually zero; you are far more likely to be bitten by a dog, get into a car accident on the 101 Freeway, or even be struck by lightning.

Ventura County illustrates the two very different worlds lions face in California. In the north, they roam the wide-open wilderness of Los Padres National Forest, a stronghold of rugged forests and brushlands where densities have been among the highest in the state. In the south, however, lions live in fragmented habitats along the edges of cities like Thousand Oaks, Simi Valley, Ojai, and Newbury Park.

Counting lions is difficult. The estimate of 4,000 to 6,000 mountain lions in California has been widely cited since the 1980s. This figure was based on habitat size and assumed lion density, but it was considered a rough estimate rather than a precise count. More recently, a study using GPS collar data and genetic analysis has estimated the population at approximately 4,500 lions statewide. Ventura County has no exact count, so scientists rely on sightings, livestock reports, and local studies.

A Modern Fight for Survival

Today, mountain lions face new human-caused threats, poisoned prey, wildfires, and roads that make survival in Ventura County more complex and perilous than the hunting pressures of the past. Freeways and urban development have cut landscapes into isolated pockets, blocking movement and reducing genetic diversity. The ten-lane U.S. Highway 101 is the biggest barrier for Santa Monica Mountains lions, with at least 32 collared animals killed since 2002. Most lions avoid crossing, and those that try rarely survive, creating a severe “genetic bottleneck.” Studies warn that without action to reconnect habitats; these populations could go extinct within 50 years in a downward spiral called an “extinction vortex.”

The Wallis Annenberg Wildlife Crossing, now under construction over the 101 freeway at Liberty Canyon, is designed to reconnect the Santa Monica Mountains with the Simi Hills and Los Padres National Forest. Though in Los Angeles County, it is critical for Ventura County’s lions, giving them the only safe route to disperse south and bring in new genes to prevent inbreeding and local extinction. Covered with native plants and shielded from traffic, the bridge will also help bobcats, coyotes, deer, and other wildlife. Completion is expected in 2026, backed by a $90 million public–private partnership inspired in part by the story of P-22, the famous Griffith Park lion.

Make History!

Support The Museum of Ventura County!

Membership

Join the Museum and you, your family, and guests will enjoy all the special benefits that make being a member of the Museum of Ventura County so worthwhile.

Support

Your donation will help support our online initiatives, keep exhibitions open and evolving, protect collections, and support education programs.

Bibliography

- “AB 117 Assembly Bill – Bill Analysis.” Official California Legislative Information. Accessed October 1, 2025. https://leginfo.ca.gov/pub/95-96/bill/asm/ab_0101-0150/ab_117_cfa_950419_140603_asm_comm.html.

- “About Mountain Lions.” Mountain Lion Foundation. Last modified August 22, 2023. https://mountainlion.org/about-mountain-lions/#!ecological-role.

- “Amendment of the California Wildlife Protection Act of 1990 (Proposition 117).” UC Law SF Scholarship Repository | UC Law SF Research. Accessed October 1, 2025. https://repository.uclawsf.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2117&context=ca_ballot_props.

- “Bill Text: CA SB818 | 2025-2026 | Regular Session | Amended.” LegiScan. Accessed October 1, 2025. https://legiscan.com/CA/text/SB818/id/3227518.

- “California enters final phase of construction on world’s largest wildlife crossing.” Governor Gavin Newsom. Last modified June 25, 2025. https://www.gov.ca.gov/2025/06/25/california-enters-final-phase-of-construction-on-worlds-largest-wildlife-crossing/.

- Camarillo Star. “Mountain Lion Claws Trainer At 1000 Oaks.” March 26, 1953, 1.

- Camarillo Star. “New fish, game laws in effect.” November 11, 1969, 9.

- Capps, Edwin S. “Mountain Lions Fare Better Than Indians in California.” Conejo News (Thousand Oaks), January 23, 1963.

- Camarillo Star. “Bags Mountain Lion with Bow and Arrows.” April 21, 193, 1.

- Clancy, Betty. “Write Angles.” Morning Free Press (Ventura), December 21, 1933, 4.

- “Community Alert: Mountain Lion Sighting.” Ventura, CA | Official Website. Accessed October 1, 2025. https://www.cityofventura.ca.gov/ArchiveCenter/ViewFile/Item/2135.

- Conejo News (Thousand Oaks). “Want Wild Pet Control Law.” September 19, 1957, 1.

- Feroben, Carolyn. “Jay Bruce – California’s Cougar Killer.” Mariposa County History and Genealogy. Accessed October 1, 2025. https://mariposacounty.sfgenealogy.org/jbrucebio.html.

- Greenfield, Carl. “I Just Found Out Some Facts About the Condor Dispute.” Ventura County Star, August 17, 1950, 2.

- “Historical Timeline.” The Cougar Fund. Accessed October 1, 2025. https://cougarfund.org/about-the-cougar/historical-timeline/.

- Holt, Bob. “Forest, Field, Surf, Stream.” Ventura County Star, March 17, 1950, 18.

- Holt, Bob. “Ventura County Forest Field Surf Stream.” Ventura County Star, June 9, 1950, 12.

- Irick, Judy. “Santa Paulan Gained Fame as Trapper of Mountain Lions.” Ventura County Star, October 30, 1965, 49.

- “John Abner “Jerky” Johnson, Jr.” Antelope Valley Rural Museum. Accessed October 1, 2025. https://avmuseum.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/AVRM-Newsletter-2021Vol5-No3.pdf.

- Kirst, John. “Taking aim at the cougar.” Ventura County Star , January 11, 1996, 42.

- “Lions in the Santa Monica Mountains – Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area (U.S. National Park Service).” NPS.gov (U.S. National Park Service). Accessed October 1, 2025. https://www.nps.gov/samo/learn/nature/pumapage.htm.

- Los Padres ForestWatch, Iris Yuh. “Protecting Wildlife Corridors in Ventura County.” ArcGIS StoryMaps. Last modified October 24, 2024. https://storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/e7cc854715aa44459ae735e5a6f606b0.

- Moorpark Star. “Two of three anti-suit questions losing.” March 27, 1996, 7.

- Morning Free Press (Ventura). “Blood Hounds Here to Get Big Lions.” January 20, 1920, 1.

- Morning Free Press (Ventura). “Editorial.” July 18, 1908, 2.

- Morning Free Press (Ventura). “Fish-Game Official Tells of Need to Kill Off Lions.” November 8, 1922, 1.

- Morning Free Press (Ventura). “He Protests Ill Treatment.” October 20, 1908, 1.

- Morning Free Press. “Huge Mountain Lion is Killed in Foster Park.” September 29, 1908, 1.

- Morning Free Press (Ventura). “Keene Paid $50 for Lion’s Skin but Santa Paulan’s Friend Did Shooting.” August 3, 1936, 1.

- Morning Free Press (Ventura). “Kill Big Lion in Sespe Canyon.” July 26, 1909, 1.

- Morning Free Press (Ventura). “Lion Hunter Returns From Haunts.” December 20, 1933, 1.

- Morning Free Press (Ventura). “Many Mountain Lions Brought In.” September 19, 1918, 4.

- Morning Free Press (Ventura). “Mountain Lion Bounty Raised.” April 19, 1935, 1.

- Morning Free Press (Ventura). “Myers Buys the Lion.” September 30, 1908, 1.

- Morning Free Press (Ventura). “No. 27 on Keene’s List.” December 13, 1936, 2.

- Morning Free Press (Ventura). “Praise Barnett’s Plan to Rid the County of Lions.” September 16, 1918, 3.

- Morning Free Press (Ventura). “Rod and Gun Members Hear Herman Keene.” May 10, 1934, 3.

- Morning Free Press (Ventura). “Skilled Woodsman Believes Only 450 Puma Still in State.” November 6, 1933, 8.

- Morning Free Press (Ventura). “Sta. Paula Nimrod Traps 100-Lb. Cat.” December 18, 1930, 3.

- “Mountain Lion – California’s Apex Predator.” Los Padres ForestWatch. Accessed October 1, 2025. https://forestwatch.org/learn-explore/wildlife-plants/mountain-lion/.

- “Mountain Lion Hunting in California: Historical Overview.” Dive Bomb Industries. Last modified 26, 2025. https://www.divebombindustries.com/blogs/news/mountain-lion-hunting-in-california-historical-overview.

- “Mountain Lion Safety.” FWS.gov. Last modified September 17, 2024. https://www.fws.gov/story/mountain-lion-safety.

- “Mountain Lions Coexist with Outdoor Recreationists by Taking the Night Shift.” UC Davis. Last modified November 26, 2024. https://www.ucdavis.edu/climate/news/mountain-lions-coexist-outdoor-recreationists-taking-night-shift.

- “Mountain Lions in California.” California Department of Fish and Wildlife. Accessed October 1, 2025. https://wildlife.ca.gov/Conservation/Mammals/Mountain-Lion.

- “Mountain Lions Terrorize California Neighborhood, Pet Safety Concerns Rise.” Newsweek. Last modified May 29, 2024. https://www.newsweek.com/mountain-lion-sightings-southern-california-1905497.

- “Mountain Lions.” Rancho Ventura. Accessed October 1, 2025. https://ranchoventura.com/mountain-lions/.

- Oxnard Press-Courier. “County Planners Delay Ordinance to Pen Wild Animals.” September 24, 1957, 1.

- Oxnard Press-Courier. “Exterminate Mt. Lions Declares Game Warden Barnett.” September 7, 1922, 1.

- Oxnard Press-Courier. “Kimbo and Major.” September 20, 1957, 20.

- Oxnard Press-Courier. “Mountain Lion Attack Victim Said Improved.” September 17, 1957.

- Oxnard Press-Courier. “Mountain Lion Clawing Victim Awarded $3,500.” April 23, 1958, 1.

- Oxnard Press-Courier. “Mountain Lion Unwanted Guest.” September 19, 1955, 1.

- Oxnard Press-Courier. “Mountain Lions Under Control in California.” June 9, 1921, 1.

- Oxnard Press-Courier. “Wild Animals.” November 20, 1957, 3.

- Oxnard Press-Courier. ““He Was on Me before I Could Run” – Boy Tells of Attack by Mountain Lion.” September 21, 1957, 9.

- Oxnard Press-Courier. “Charms Lion With Harmonica Music.” April 18, 1913, 1.

- Paul, Jr., Joe. “Fillmore Children Captivated by Six-Week-Old Lion Kitten.” Ventura County Star, May 23, 1950, 1.

- Paul, Jr., Joe. “Looking At Ventura County.” The Ventura Weekly Post and Democrat, September 23, 1949, 2.

- Paul, Jr., Joe. “Looking at Ventura County.” The Ventura Weekly Post and Democrat, December 30, 1949, 2.

- Paul, Jr., Joe. “Mountain Lion Just About Gone.” Ventura County Star, March 9, 1971, 9.

- Paul, Jr., Joe. “Reporting.” Ventura County Star, January 6, 1961, 13.

- “A President’s Unexpected Legacy.” The Cougar Fund. Accessed October 1, 2025. https://cougarfund.org/a-presidents-unexpected-legacy/.

- “Protect Our Local Mountain Lions — Citizens for Los Angeles Wildlife.” Citizens for Los Angeles Wildlife. Accessed October 1, 2025. https://www.clawonline.org/protect-local-mountain-lions.

- “Puma Profiles – Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area (U.S. National Park Service).” NPS.gov (U.S. National Park Service). Accessed October 1, 2025. https://www.nps.gov/samo/learn/nature/puma-profiles.htm.

- “Room to Roam – Protecting Wildlife.” Los Padres ForestWatch. Accessed October 1, 2025. https://forestwatch.org/what-we-do/protecting-wildlife/room-to-roam/.

- “Saving California Mountain Lions: Our Campaign.” Center for Biological Diversity. Accessed October 1, 2025. https://www.biologicaldiversity.org/species/mammals/California-mountain-lion/our-campaign.html.

- “Scientists Tracked These Mountain Lions in Los Angeles for Seven Years – Now They’ve Discovered Something Crucial.” Discover Wildlife. Last modified November 14, 2024. https://www.discoverwildlife.com/animal-facts/mountain-lions-los-angeles.

- Sheridan, E. M. “Pioneer, With Help of Dog, Slays Big Lion Bare-Handed.” Ventura County Star, December 26, 1929, 11.

- Simi Valley Star. “Captured Lion Dies; Will be Mounted.” November 5, 1931, 5.

- Simi Valley Star. “Captures Lion Bare Handed.” December 27, 1963, 1.

- Simi Valley Star. “Lion Hunter.” June 20, 1957, 2.

- Simi Valley Star. “Lion hunter Herman Keene to Seek the ‘Lion of the Alamo’.” October 12, 1939, 6.

- Simi Valley Star. “Lion’s Skin Given Club.” February 4, 1932, 1.

- Simi Valley Star. “Lions: Bill to bite hunter.” June 9, 1971, 10.

- Simi Valley Star. “McClintock Takes Sides on Measures.” May 22, 1990, 2.

- Simi Valley Star. “No Bounty for Warren, Moorpark Lion Killer.” August 9, 1963, 1.

- Simi Valley Star. “When We Used to Shoot Lions in Our Back Yard.” February 2, 1922, 4.

- Sparks, Henry. “Fred Ortega, Ojai, Recalls Capturing Mountain Lion.” Ventura County Star, June 3, 1937.

- Staff. “Fractured Genetic Connectivity Threatens a Southern California Puma Population.” Mountain Lion Foundation. Last modified July 8, 2021. https://mountainlion.org/2014/10/27/fractured-genetic-connectivity-threatens-a-southern-california-puma-population/.

- “Temporal trends and drivers of mountain lion depredation in California.” DigitalCommons@USU | Utah State University Research. Last modified 2021. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1712&context=hwi.

- Thousand Oaks Star. “City opposes mountain lion measure.” March 4, 1996, 3.

- Thousand Oaks Star. “Kill lions to find if endangered?” September 20, 1971, 7.

- Thousand Oaks Star. “Mountain lion – switch of roles wins state’s favor.” January 24, 1971, 14.

- Thousand Oaks Star. “Pet Lion Charges Deputy.” April 7, 1969, 1.

- Thousand Oaks Star. “Prop 197 What to Do About Lions.” March 19, 1996, 84.

- Thousand Oaks Star. “Prop. 117 is not what it seems to be.” May 21, 1990, 12.

- Thousand Oaks Star. “Prop. 117: Vote ‘Yes’.” May 25, 1990, 12.

- Thousand Oaks Star. “State Chooses to Study, Not Hunt Lions.” April 8, 1986, 14.

- Thousand Oaks Star. “The Day in Sacramento.” March 7, 1969, 10.

- Ventura County Star. “$50,000 Suit Filed Over Lion Attack.” October 8, 1957, 1.

- Ventura County Star. “‘One-Legged Lion’ Tracks Cover Beach.” March 10, 1954, 2.

- Ventura County Star. “Bill To Save Mountain Lions Introduced in Assembly.” February 26, 1971, 3.

- Ventura County Star. “Board Curbs Loose Wild Animals New County Edict.” June 30, 1958, 1.

- Ventura County Star. “Bounty Pay a Mistake?” September 6, 1962, 32.

- Ventura County Star. “Boxers, Wildlife Species Getting Help From State.” December 30, 1971, 14.

- Ventura County Star. “Bruce Hunting Near San Diego.” January 12, 1927, 7.

- Ventura County Star. “Bruce Kills 25 More Lions.” December 30, 1931, 7.

- Ventura County Star. “COUGARS: Ballot measure revisits an issue raised by Proposition 1990 proposition.” February 25, 1996, 48.

- Ventura County Star. “Cattlemen Deny Prop. 117 Ambush.” March 23, 1990, 29.

- Ventura County Star. “Clark To Confer on Uniform Lion Bounty.” April 5, 1935, 1.

- Ventura County Star. “Commission Grants Local Cougars Temporary Protection.” April 18, 2020, 1.

- Ventura County Star. “Creature Count: From newt to condor, county has 383 species.” April 11, 1986, 27.

- Ventura County Star. “Famed Lion Trapper Celebrates 74th Year.” December 27, 1952, 2.

- Ventura County Star. “Fillmore Girl Proud Owner of Six-Week-Old Lion Cub.” May 22, 1950, 2.

- Ventura County Star. “Grace for Lions in Sacramento.” April 1, 1971, 32.

- Ventura County Star. “Guest Columnist Reporting.” August 8, 1957, 15.

- Ventura County Star. “Herman Keene Bags 130-Pound Cougar.” March 16, 1950, 1.

- Ventura County Star. “Herman Keene Brings Live Mountain Lion to Ventura.” November 24, 1937, 3.

- Ventura County Star. “Herman Keene’s Lion Hunting Is Subject of Magazine Article.” April 9, 1935, 2.

- Ventura County Star. “Herman Keene, 86, Dies; Lion Hunter, Outdoorsman.” December 27, 1965, 36.

- Ventura County Star. “Hunting law enables cougars to flourish.” January 4, 1995, 7.

- Ventura County Star. “Jay Bruce Bags Mountain Lion.” April 19, 1926, 6.

- Ventura County Star. “Jay Bruce Increases Number of Notches in Rifle to 284.” November 20, 1926, 7.

- Ventura County Star. “Keene Captures Mountain Lion; Club to Get It.” October 27, 1931, 3.

- Ventura County Star. “Keene Exhibits Lion, Shot by Son and Friend.” December 7, 1939, 1.

- Ventura County Star. “Keene Uses Bow and Arrow to Kill Lion.” April 14, 1933, 1.

- Ventura County Star. “Killing Animals.” July 16, 1959, 36.

- Ventura County Star. “Killing Lions Unnecessary.” March 20, 1996, 41.

- Ventura County Star. “Lion Bill Starts Mutiny on Bounty.” May 20, 1963, 20.

- Ventura County Star. “Lion Bounty.” March 8, 1961, 5.

- Ventura County Star. “Lion On Tour Visits City.” August 24, 1927, 1.

- Ventura County Star. “Masons to Hear Lion Hunter.” July 31, 1934, 10.

- Ventura County Star. “Mountain Lion Bounty Sought.” January 7, 1930, 1.

- Ventura County Star. “Mountain Lion Costly Animal.” March 26, 1930, 1.

- Ventura County Star. “Mountain Lion Hunting Season Cut To 3½ Months.” May 24, 1971, 24.

- Ventura County Star. “Mountain Lion Mauls Film Producer on Set.” February 9, 1949, 16.

- Ventura County Star. “Mountain Lion Tags on Sale at DFG.” November 11, 1971, 31.

- Ventura County Star. “Mountain Lion, Cougar Protected.” November 13, 1969, 27.

- Ventura County Star. “Mountain Lion.” October 9, 1959, 30.

- Ventura County Star. “Mountain Lions Not So Scarce After All.” September 9, 1971, 34.

- Ventura County Star. “Mountain Lions Offer ‘New’ Game.” July 5, 1962, 14.

- Ventura County Star. “Mountain Lions.” May 9, 1971, 28.

- Ventura County Star. “Mountain Lions.” March 24, 1971, 44.

- Ventura County Star. “New State Fight Looms to Save Mountain Lion.” May 21, 1972, 32.

- Ventura County Star. “People admire awesome cats’ beauty, charm.” March 10, 1996, 6.

- Ventura County Star. “Pet Mountain Lion Mauls Youngster, Men Battle Beast.” September 16, 1957, 1.

- Ventura County Star. “Planners Slate Talks on County Wild Animal Ban.” September 24, 1957, 11.

- Ventura County Star. “Prop 117 could put DFG in financial jam.” June 15, 1990, 18.

- Ventura County Star. “Rick Brazil On Outdoors.” January 29, 1959, 18.

- Ventura County Star. “Santa Paulan Meets a Lion.” June 30, 1926, 1.

- Ventura County Star. “Second Lion Kill.” January 27, 1959, 11.

- Ventura County Star. “Sheep Killer.” November 26, 1938, 4.

- Ventura County Star. “Squeaky to Get Screen Test.” June 10, 1950, 9.

- Ventura County Star. “Summary from Sacramento.” June 18, 1963, 13.

- Ventura County Star. “The Varmints.” March 6, 1959, 20.

- Ventura County Star. “Too Few Lions Left, County May End Bounty.” December 27, 1960, 18.

- Ventura County Star. “Two views on mountain lions.” March 12, 1996, 35.

- Ventura County Star. “Victim of Lion Attack Begins Shots for Rabies.” September 17, 1957, 1.

- Ventura County Star. “Wants More Facts.” September 20, 1957, 24.

- Ventura County Star. “What People Are Doing.” September 13, 1926, 8.

- Ventura County Star. “What? No Bounty on Lions.” March 31, 1962, 2.

- Ventura County Star. “Wild Animals as “Pets”.” September 17, 1957, 20.

- Ventura Free Press. “From Saturday’s Daily.” December 10, 1886, 3.

- Ventura Free Press. “Mountaineer and Hunter Meets Untimely Death.” January 1, 1915, 1.

- Ventura Free Press. “Ojai Happenings.” April 21, 1893, 2.

- Ventura Free Press. “Ojai Happenings.” February 17, 1893, 8.

- Ventura Free Press. “Saticoy Sightings.” August 26, 1892, 8.

- Ventura Free Press. “The Head of a Mountain Lion.” February 17, 1893, 5.

- The Ventura Weekly Post and Democrat. “Buckhorn Club.” October 2, 1908, 7.

- The Ventura Weekly Post and Democrat. “Editorial.” March 21, 1913, 2.

- The Ventura Weekly Post and Democrat. “Editorial.” September 15, 1922, 2.

- The Ventura Weekly Post and Democrat. “Game and Wild Animals.” January 20, 1887, 3.

- The Ventura Weekly Post and Democrat. “How to Secure Mountain Lion $20 Bounty.” February 7, 1913, 4.

- The Ventura Weekly Post and Democrat. “Huge Mountain Lion Slain.” October 2, 1908, 3.

- The Ventura Weekly Post and Democrat. “Hunting Licenses and Benefits of the Law.” July 3, 1908, 2.

- The Ventura Weekly Post and Democrat. “Hunts Lions With Dogs and Revolver.” March 19, 1926, 3.

- The Ventura Weekly Post and Democrat. “Local News.” October 4, 1918, 4.

- The Ventura Weekly Post and Democrat. “Mountain Lion Hunter Now on Job.” July 4, 1919, 2.

- The Ventura Weekly Post and Democrat. “Mountain Lion, With Appetite for Kids and Pigs, Though Peppered With Fine Shot Still Raising Dickens in the Mountains.” July 17, 1914, 1.

- The Ventura Weekly Post and Democrat. “Mountain Lions.” March 10, 1887, 1.

- The Ventura Weekly Post and Democrat. “Moving Picture Company Will Go Along on Mountain Lion Hunt.” July 26, 1918, 5.

- The Ventura Weekly Post and Democrat. “Of Local Interest.” October 23, 1908, 5.

- The Ventura Weekly Post and Democrat. “The Buckhorn Club.” September 11, 1908, 4.

- The Ventura Weekly Post and Democrat. “The Ojai.” September 24, 1920, 5.

- The Ventura Weekly Post and Democrat. “Ventura Resorts.” April 13, 1906.

- The Ventura Weekly Post and Democrat. “Wednesday.” April 17, 1908, 5.

- “VenturaCountyTrails.org News.” Ventura County Trails. Accessed October 1, 2025. https://venturacountytrails.org/WP/category/wildlife/mountain-lions/.

- “Verified Mountain Lion-Human Attacks.” California Department of Fish and Wildlife. Accessed October 1, 2025. https://wildlife.ca.gov/Conservation/Mammals/Mountain-Lion/Attacks.

- “Wallis Annenberg Wildlife Crossing.” DH Charles Engineering. Accessed October 1, 2025. https://charlesengineering.com/wallis-annenberg-wildlife-crossing/.

- “Wildlife Corridor is Critical.” Sierra Club. Accessed October 1, 2025. https://www.sierraclub.org/los-padres/blog/2020/10/wildlife-corridor-critical.

- “Wildlife Crossing.” Santa Monica Mountains Fund. Accessed October 1, 2025. https://samofund.org/wildlife-crossing/.