by Library Docent Volunteer Andy Ludlum

Juan Marion stood in the dark ocean, water up to his neck. The cold January waves made him gasp. The shock numbed the pain from the bullet that grazed his side and the handcuffs that cut into his wrists. He stayed still, watching as sheriff’s deputies swept the Santa Clara riverbed and the ocean with their flashlights, looking for him.

It was 1923. Marion, a burglar, had been arrested by Ventura County Sheriff Robert Clark. As they neared the county jail, Marion suddenly jumped from the sheriff’s car and ran toward the water. The officers stopped and fired at him, but he disappeared into the darkness. He stumbled through the marshy estuary, leaving tracks in the wet sand where he had fallen several times. Marion reached the ocean and hid in the deep water until the deputies moved on. Then he waded back toward shore, walking through waist-deep water until he reached the beach near the old Chautauqua building. He came ashore and escaped over the sand dunes.

Ventura County’s most notorious burglar of the 1920s had slipped through the hands of the law. It wasn’t the first time, and it wouldn’t be the last.

Prison records show that Marion was born in “Lower California,” the name once used for the Baja California peninsula. He grew up in Pomona and was known there as “Johnnie Marrione”. In 1911, at just 15 years old, Marion got into a drunken knife fight with a man named Alex Ybarra. He stabbed Ybarra in the wrist with a jackknife, cutting so deep that it severed Ybarra’s tendons. A night watchman caught Marion and took him to jail, where he was charged with assault with a deadly weapon. At his arraignment, another charge was added: burglary of the home of Pomona orange rancher Charles Richardson.

While Charles Richardson was away delivering oranges to the packing house, someone broke into his home. His gold watch, an automatic revolver, a pearl-handled knife, and other valuables were stolen. Constable Frank O. Slanker began investigating. He noticed a young man in a secluded spot winding a gold watch, one that looked too expensive for someone his age. When Slanker questioned him, the young man admitted he got the watch from Marion. When Marion was shown the watch and the pearl-handled knife, he confessed. He then told Slanker that the rest of the stolen items were in his room at his grandfather’s house on West Second Street.

Teenage Marion Makes His First Escape

Marion now faced charges of assault and burglary in Superior Court. While awaiting trial, he was sent to a Los Angeles detention home for juveniles, meant to keep young offenders separate from adults. The Pomona Morning Times warned that if Marion continued on his current path, he could become a hardened criminal. Still, the paper held out hope, saying that if he was helped now there might be a chance to turn his life around because, as they put it, “there is always some good in everyone.” Just a few days later, Marion escaped from the Los Angeles detention home and vanished without a trace. The Pomona Morning Times expressed regret, saying he had thrown away his chance to turn his life around and was “in danger of landing in the penitentiary for a long term.”

Although Marion vanished from Pomona, Constable Slanker kept investigating and found more evidence linking him to other crimes. While searching Marion’s room at his grandfather’s house, Slanker noticed handlebars that matched a motorcycle stolen from T.D. Parker seven months earlier. He discovered that Marion and a friend had hidden the bike under Marion’s bed for months. Later, they took it apart, putting the engine in another motorcycle, swapping parts, and repainting both bikes to hide their identity. Slanker recovered both motorcycles and kept looking for Marion’s accomplice.

Marion laid low for five years. Then, in late 1914, Constable Slanker received a letter from him, postmarked from Las Vegas. According to the Pomona Progress-Bulletin, Marion expressed regret for his past actions and asked for a chance to return to Pomona and live an honest life. He said he was now 20 years old and that his grandfather was “old and feeble” and needed his help. Marion promised to “come back and work and be good” if given the chance. Slanker agreed and told him to return and try to stick to his good intentions.

“One of the Meanest Deeds”

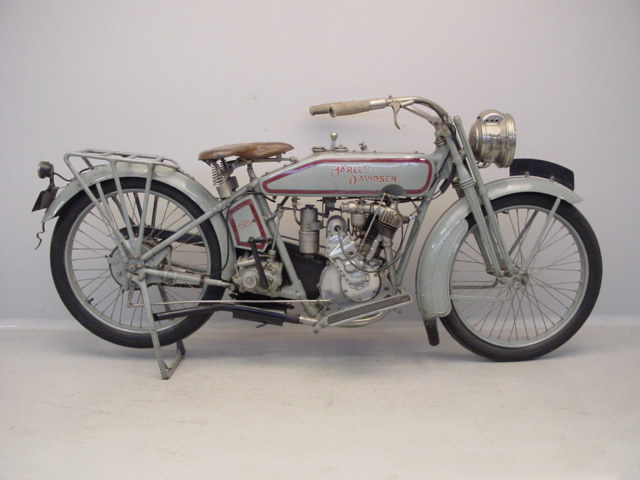

At 4:30 a.m. on July 14, 1916, Al Blatz, described by the Pomona Progress-Bulletin as a “worthy young youth,” was getting ready to start his paper route. He went out to the woodshed to get his Harley-Davidson motorcycle, which was newly paid off. Blatz depended on the income from his paper route to help support his family. His father, L.A. Blatz was recently injured in a car accident and recovering from a compound fracture in his left leg. His brother Ed was called away to Nogales with his National Guard unit because of growing tensions along the U.S.-Mexico border. When Blatz opened the shed, the motorcycle was gone. The Progress-Bulletin called it “one of the meanest deeds committed in the city.”

Police searched the nearby roads but found no trace of the thief, or anyone who had seen the stolen motorcycle. Constable Slanker, who gave Marion a second chance less than two years earlier, quickly grew suspicious. Familiar with Marion’s habits, he distributed a printed description to law enforcement agencies across California.

Two months later, in September, a deputy constable spotted the stolen Harley, now damaged, parked near a store in Walnut. A man named Phillip Eavera told police, “I came out of the store and smelled gasoline evaporating. Upon looking at my machine I found that the gas was running. About that time Johnnie came up and asked me if he could borrow a little gasoline from the tank on my machine, I said yes, but before he started to take it, I noticed that my kit of tools was gone from the machine. The glass front of my headlight was also gone. I saw some of the tools sticking out from under [his] right arm. I asked him if he took my tools and he didn’t answer me, but he turned and ran into the woods at the side of the road.” With Eavera’s description, the manhunt for Marion resumed. A constable at the Oxnard beet sugar factory arrested a man matching Marion’s description, but the man escaped.

Funeral Deception Pays Off

In January 1917, Marion’s grandfather, A. Valino Garcia, a pioneer restaurant owner in Pomona, died. Constable Slanker believed Marion might return for the funeral. He came up with a clever ruse: he told an acquaintance of Marion’s father, “I think Johnnie will come home for the funeral, and if he does, I’ll not go after him Saturday nor Sunday, but if he is here on Monday I’ll get him.” The message came back: “Johnnie wouldn’t be around here on Monday.” Slanker attended the Saturday funeral and when he didn’t spot Marion, he went to the family home, where he found and arrested him.

On February 21, 1917, Marion pleaded guilty to stealing the motorcycle. His lawyer, U.E. White, asked the judge for probation, but the request was denied after testimony revealed Marion’s juvenile record of burglary, parole violations, and past thefts. He was sentenced to three years in San Quentin, the state’s main entry prison for first-time male offenders. The judge called it a light sentence for a grand larceny conviction. Al Blatz eventually got his motorcycle back, though it cost him about $75, roughly $1,884 today, to repair.

Paroled After Just 38 Days

Marion spent just 38 days in San Quentin before being paroled on April 1, 1917. While that may seem short for a three-year sentence, it was possible under California’s Indeterminate Sentence Law, which went into effect that year. Instead of serving a fixed term, inmates could be released early based on their behavior and potential for rehabilitation. The law aimed to “make the punishment fit the criminal rather than the crime.” Since Marion was a first-time offender and his crime of motorcycle theft was a non-violent property offense, the State Board of Prison Directors saw no reason to keep him behind bars longer.

In 1917, parole in California was still a new and developing system. It lacked the structure and oversight of modern parole. Instead of being assigned a parole officer, most parolees were supervised by the State Board of Prison Directors. They were usually required to check in monthly, often by mail, with the prison or a board representative. Parolees were expected to stay out of trouble, find steady work and housing, and keep authorities informed of their whereabouts. Their focus was to show they had reformed and could live responsibly outside prison. But Marion didn’t hold up his end of the deal; he violated his parole and disappeared.

Rancher Spots Something Strange

Over the next few years, Marion stayed out of the law’s reach while leading a gang that committed dozens of robberies across Ventura and Los Angeles counties. They targeted homes, stores, and railroad boxcars and tool sheds in places like San Fernando, Chatsworth, Owensmouth (now part of Canoga Park), Somis, Simi Valley, and Santa Susana. When one of Marion’s accomplices, an 18-year-old, was arrested in 1923, he admitted he had “been in the game” for four years.

Late in 1922, rancher John Graves was riding horseback in the hills near the top of the Santa Susana Pass when he spotted three men loading car tires into a beat-up vehicle. Curious, Graves rode closer, but as soon as the men saw him, they sped off. The road was rough, but Graves managed to keep them in sight until dusk, when he watched them disappear into a canyon at the end of an old, unused trail just across the Ventura County line. Suspecting an ambush if he went any farther, Graves turned back to Chatsworth and alerted the sheriff.

By the time deputies arrived, the men were gone. Searching the area with flashlights, they eventually found a hidden grotto beneath an overhanging cliff. Tucked behind cut brush, the stolen goods were carefully stashed under a tarpaulin. Deputies discovered a car and a motorcycle with the plates and registration removed, four typewriters, $1,000 worth of canned food, $2,000 in cigars, cigarettes, and candy, and thirty-five car tires. Most of the stolen items were traced to a series of recent robberies in Simi Valley and a break-in at a Southern Pacific freight depot.

“Robbery Almost Every Night”

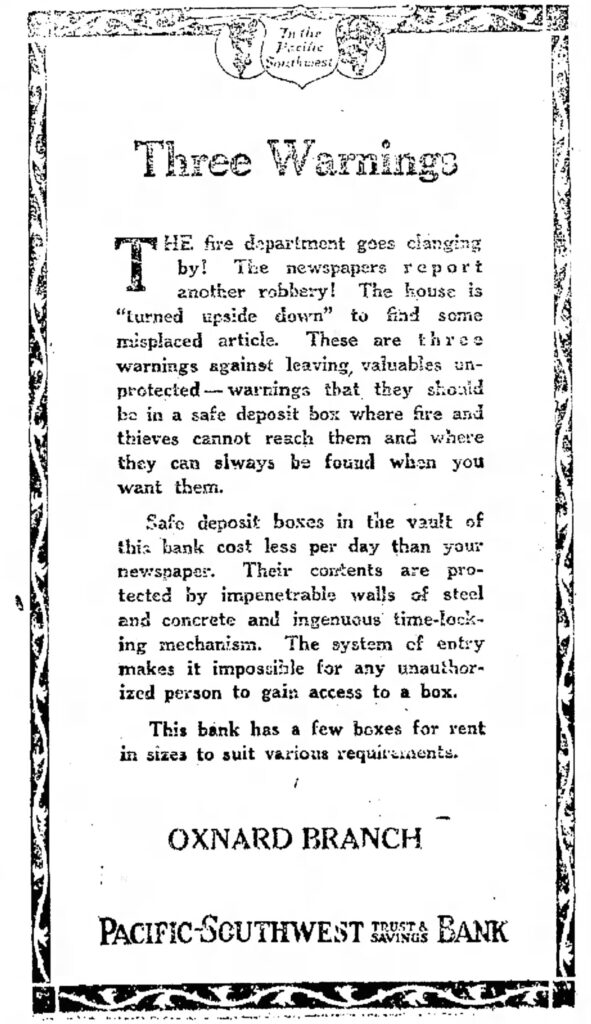

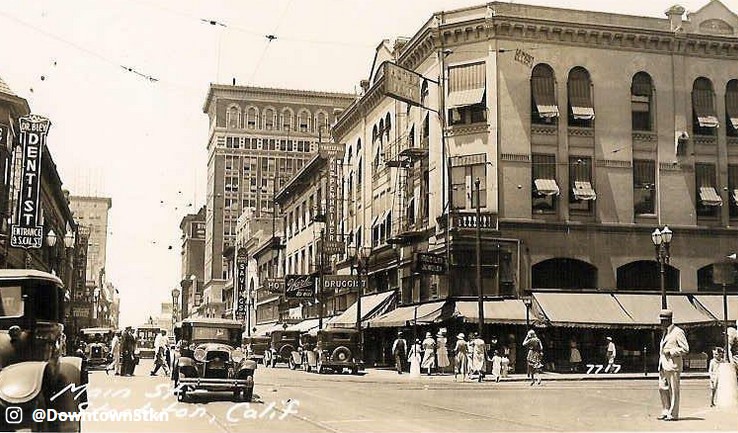

In 1923, readers of Ventura County newspapers were regularly confronted with reports of crime. Burglaries were so common that The Ventura Weekly Post and Democrat opened the year by noting that the “east end of the county is seeing its usual robbery almost every night.” Crime was a constant subject in the local papers and many of these articles reflected a clear sense of public fear. The tone often went beyond basic reporting. Headlines used dramatic phrases like “terrorizing the Simi valley” and “Chloroform Burglars Menace Santa Barbara.” A February letter to the editor of The Ventura Weekly Post and Democrat spoke of a “great wave of crime which enveloped all of America and especially California.”

In January 1923, burglars broke into the Santa Susana home of H.J. Crinklaw—also known as Horace Crinklaw, a key figure in the town’s early development. Crinklaw and his wife, Eva, operated the community’s first general store since 1909, located across Los Angeles Avenue from the train station. The break-in occurred between 6 and 9 p.m., while the family was away. Among the stolen items were a revolver, a rifle, several furs, articles of clothing, and a phonograph, a luxury item in its day. (A popular Victor Victrola VV-215 phonograph sold for $150 in 1923, about $2,300 today.)

Marion Escapes in Handcuffs After Hueneme Raid

Railroad Special Investigator George Alford and his assistant, J.J. McInerney, were assigned to investigate the depot robberies. Among the stolen goods recovered in Santa Susana was an undeveloped roll of film. After developing the photos, copies were sent to police in Ventura and Los Angeles counties. A deputy in Somis believed he recognized one of the men as the person who robbed a local store. Following that lead, investigators tracked down Gobina Gobia, who was found with cans of coffee suspected to have been stolen from a railroad camp. Gobina admitted he bought the coffee from a man named “Juan” and another man known only as “Smith.” He said they lived near Oxnard or Hueneme—he wasn’t sure which. Alford contacted Sheriff Clark, and the two headed to Hueneme. There, they learned that two men matching the suspects’ descriptions recently rented a shack from a man named C.I. Gillmore. Locals said the men acted suspiciously.

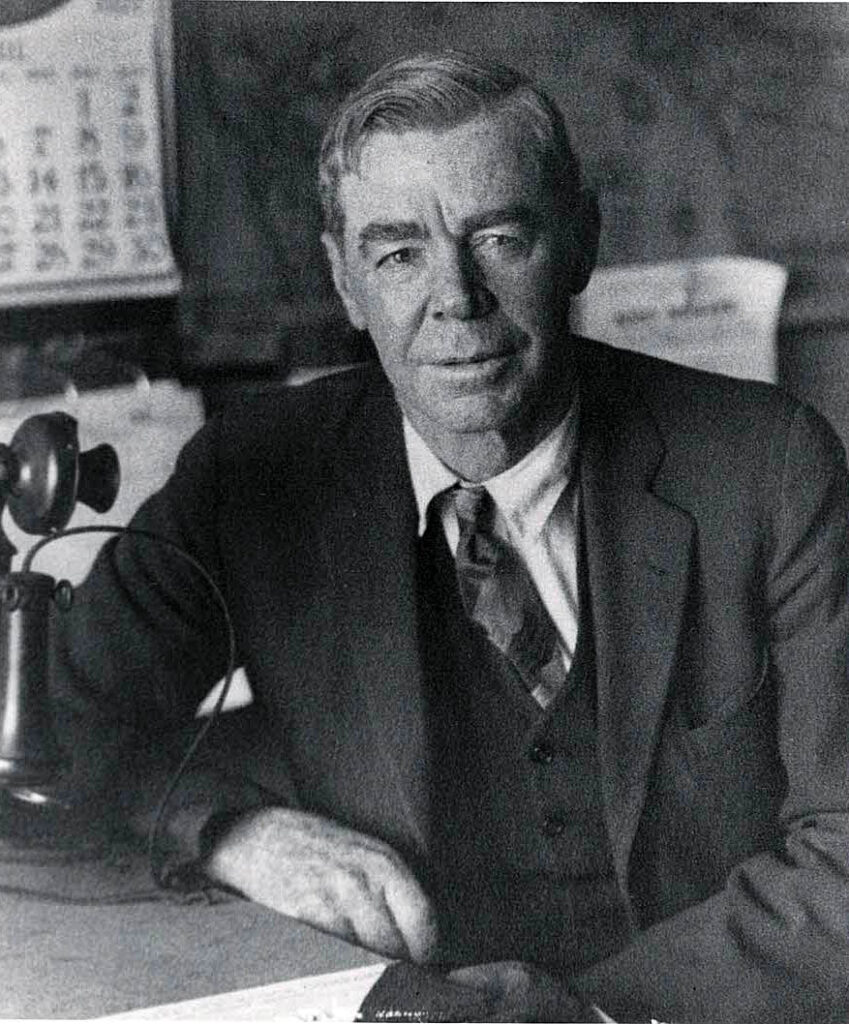

On January 19, 1923, railroad investigators Alford and McInerney joined Ventura County Sheriff Clark, Deputy Sheriff Pablo Ayala, and Somis Deputy L.W. Wells to raid the house in Hueneme, located just across the street from the local school. Outside the house was a Dodge commercial vehicle. As the officers approached, a man hurried out and drove off in the Dodge. Sheriff Clark chased him down and arrested him. The man gave his name as Henry Hodges, but he was also known as Henry Smith.

Meanwhile, Alford and McInerney knocked on the front door. Marion answered but refused to let them in. Alford forced the door open and snapped handcuffs on Marion, who tried to reach for a pistol in his back pocket. Alford was faster, and with McInerney’s help, they wrestled him down. A Winchester rifle was standing beside the door, and another pistol was found under Marion’s pillow.

Inside the house, officers were stunned by the amount of stolen property. They found piles of men’s and women’s clothing, silks, satins, a phonograph, a tray of brand-new revolvers, and many items taken from the Crinklaw home in Santa Susana, as well as from Southern Pacific boxcars and tool houses. The Dodge truck had also been reported as stolen in Los Angeles. Marion and Smith were taken to Ventura. Alford brought Smith to the courthouse to check records related to earlier robberies. The 18-year-old quickly confessed to the Crinklaw burglary, the Somis robbery, and dozens of thefts from railroad boxcars and tool sheds. At the same time, Sheriff Clark was driving Marion to the county jail when Marion, still handcuffed, jumped from the car and escaped to the ocean. “These fellows were the roughest I have ever seen,” said Investigator Alford. “They are bad, absolutely bad. If we hadn’t stormed that house the moment we arrived, we never would’ve made it out alive. They were armed and ready for a fight. This was one of the most dangerous gangs we’ve dealt with in a long time.”

A Crime Spree Across Southern California

Marion reunited with another member of his gang, a young woman from Oxnard named Dora Dominguez. Together they led sheriff’s deputies on a ten-month chase across Southern California. During that time, the pair committed more than 50 robberies, targeting ranch houses and stores in Los Angeles, San Bernardino, and Ventura counties. In November, after months of pursuit, Sheriff Clark finally tracked them to a hideout in Azusa. Marion, according to Clark, admitted he’d committed several Ventura County robberies and returned with him to Ventura for trial. Dominguez remained in jail in San Bernardino.

On November 14, Marion seemed in good spirits as he was brought to the Ventura County Courthouse for a preliminary hearing on charges of burglarizing Crinklaw’s home in Santa Susana. He let out a whoop and told Deputy Sheriff Ayala in Spanish, “The world is beautiful.” At the hearing, Crinklaw took the stand and identified a rifle, a violin, and clothing that Marion had stolen. Marion was ordered to stand trial in Superior Court and held on $10,000 bail, about $188,000 today. Unable to pay bail, Marion was taken back to county jail, where, according to the Oxnard Press-Courier, several of his women friends came to talk to him through the bars of his cell.

Hanging in the Jail Shower

While upbeat when entering his preliminary hearing, once back in jail Marion became “sullen and sulky,” according to The Ventura Weekly Post and Democrat. For the next three days, he paced his cell nonstop, repeatedly called out Dominguez’s name, and threatened to kill himself. At the time of his arrest, Marion had $218 on him, $200 of which he arranged to send to Dominguez. Meanwhile, in San Bernardino, Dominguez was facing her own charges for robbing a store in Alta Loma. The court was told she wore a dress stolen from the store at the time of her arrest. She was held in jail, unable to post $2,000 bail.

On the evening of November 21, around 6:30 p.m., Marion was found hanging from the shower in his jail cell, using a rope made from a canvas shower curtain. Two inmates upstairs heard groans coming from his cell and alerted the jailer. When the jailer entered, Marion was still kicking his feet against the floor. He quickly cut Marion down and moved him to a more secure inner cell, then called Sheriff Clark and a doctor. When they arrived, Marion was lying on his bunk, talking to himself. The doctor found nothing physically wrong. Both the sheriff and jailer suspected Marion was faking insanity. They believed the incident may have been a ploy to lure an officer into an unlocked cell and attempt an escape. As a precaution, the shower curtain was removed from the cell.

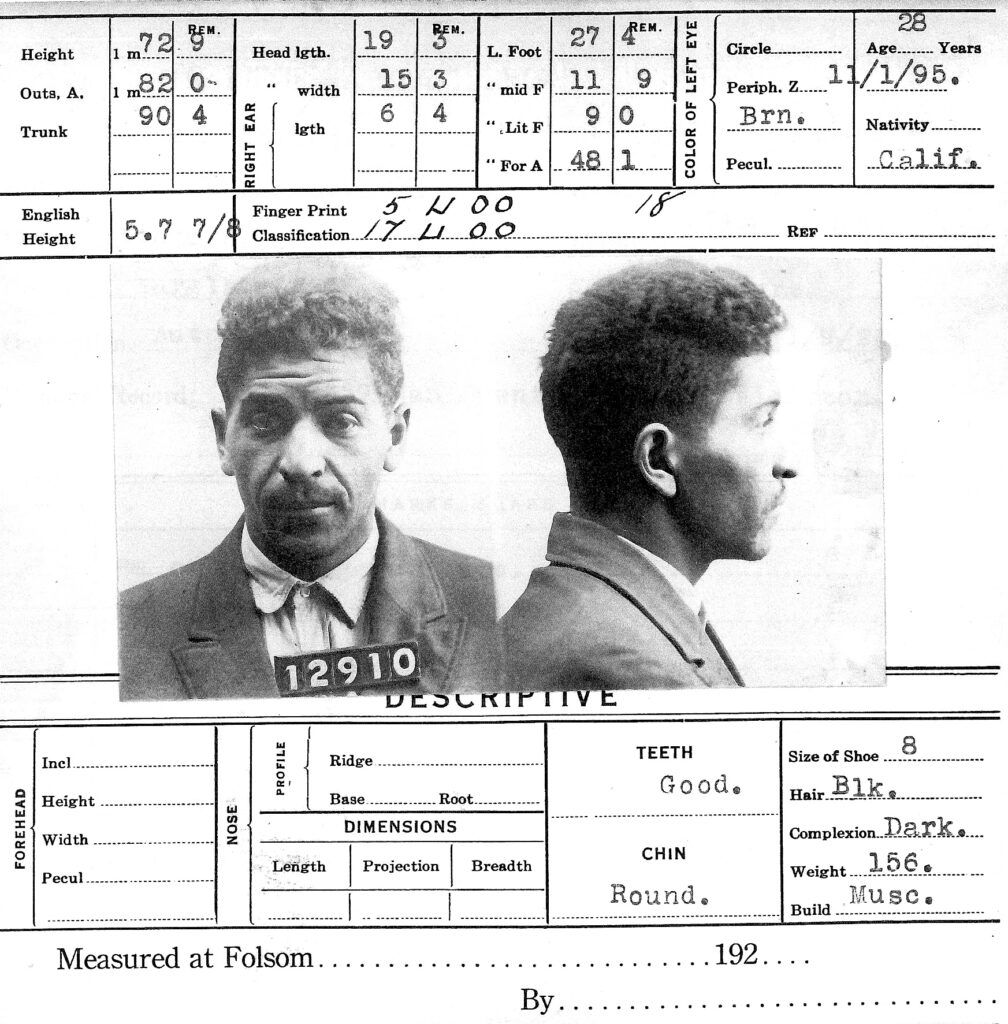

Measured in Santa Barbara

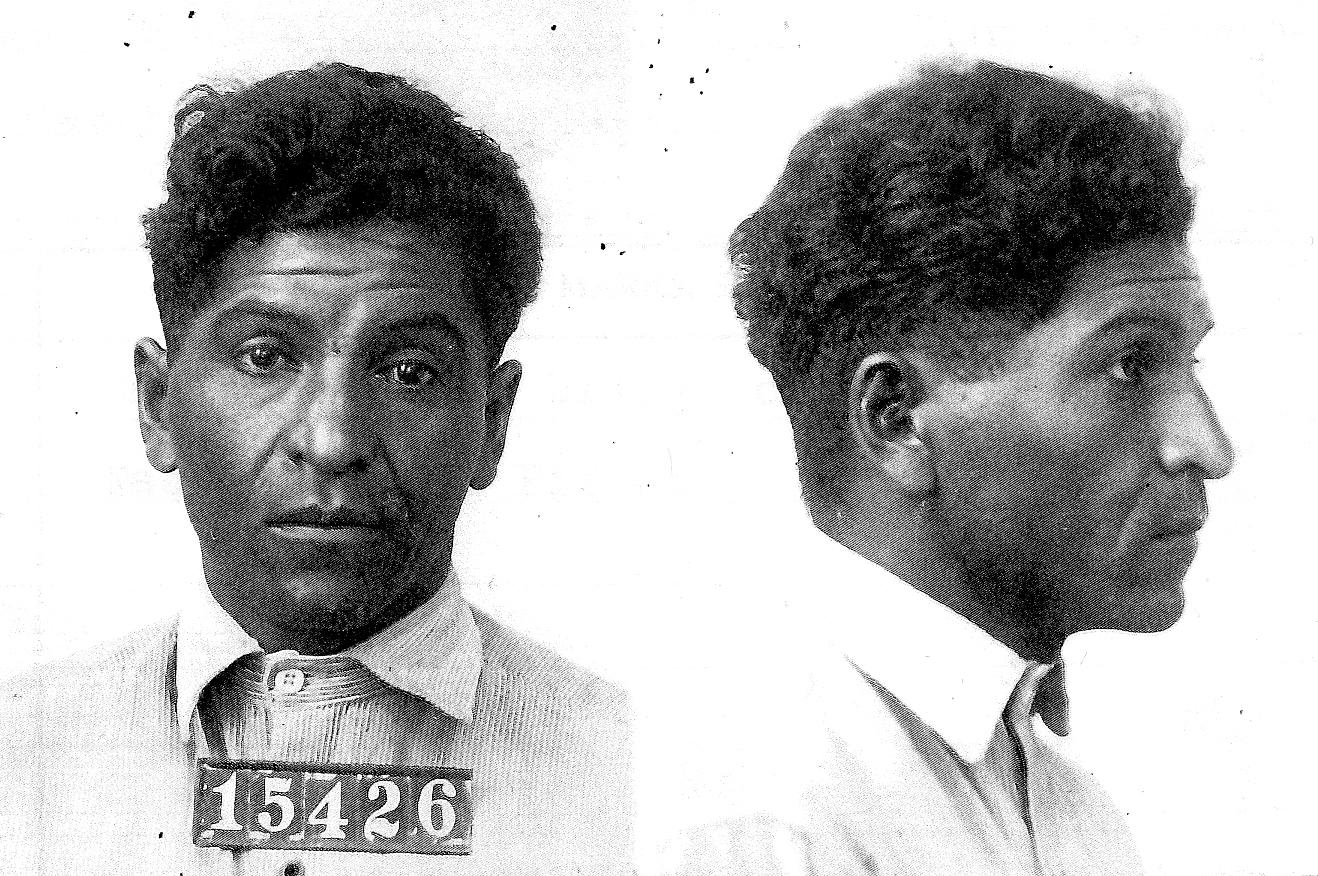

Shortly after his suicide attempt, Marion was taken to Santa Barbara for Bertillon measurements. The Bertillon system, developed in 1879 by French anthropologist Alphonse Bertillon, identified criminals via precise body measurements, physical descriptions, and mug shots. The Bertillon system required specialized tools and training to take precise body measurements and standardized photographs. In this era of limited forensic tools, lack of information and poor coordination between jurisdictions often meant criminals like Marion avoided identification and capture. Larger counties like Santa Barbara served as regional centers for advanced identification procedures. Though innovative for its time, the method was flawed as body measurements could change. The system was gradually phased out and officially replaced by the fingerprint system in 1927.

“They Won’t Fall for It”

Marion was arraigned on December 5. His lawyer, Scott McReynolds, tried to enter an insanity plea, but two doctors convinced the judge that Marion was sane, and the arraignment went on. According to the Ventura Morning Free Press, Marion tried to stall by pretending he didn’t understand and needed an interpreter. He eventually pleaded not guilty to first-degree burglary, and the trial was set for January 3. Two days later, The Ventura Weekly Post and Democrat reported that Marion gave up pretending to be insane, reportedly telling his jailer, “It’s no use, they won’t fall for it.”A week later, Sheriff Clark took Marion to San Bernardino to testify in Dominguez’s preliminary hearing. The 22-year-old woman was ordered to stand trial for burglary.

On January 3, 1924, just as his trial was about to begin, Marion pleaded guilty to the Ventura County charges before Judge Merle J. Rogers. He also confessed to robbing the general store in Alta Loma and insisted his girlfriend Dominguez had nothing to do with it. With Marion’s confession and weak evidence against her, San Bernardino officials admitted a conviction was unlikely and said she would probably be released. Since Marion confessed to the Ventura burglary, he wouldn’t be tried in San Bernardino.

He offered to show Sheriff Clark where the stolen goods were hidden. On January 6, under heavy guard, Marion led Clark and the San Bernardino Sheriff to a dry wash in a remote canyon seven miles from Perris, where they dug up clothing worth $1,500 to $2,000, wrapped in canvas and buried eight feet deep.

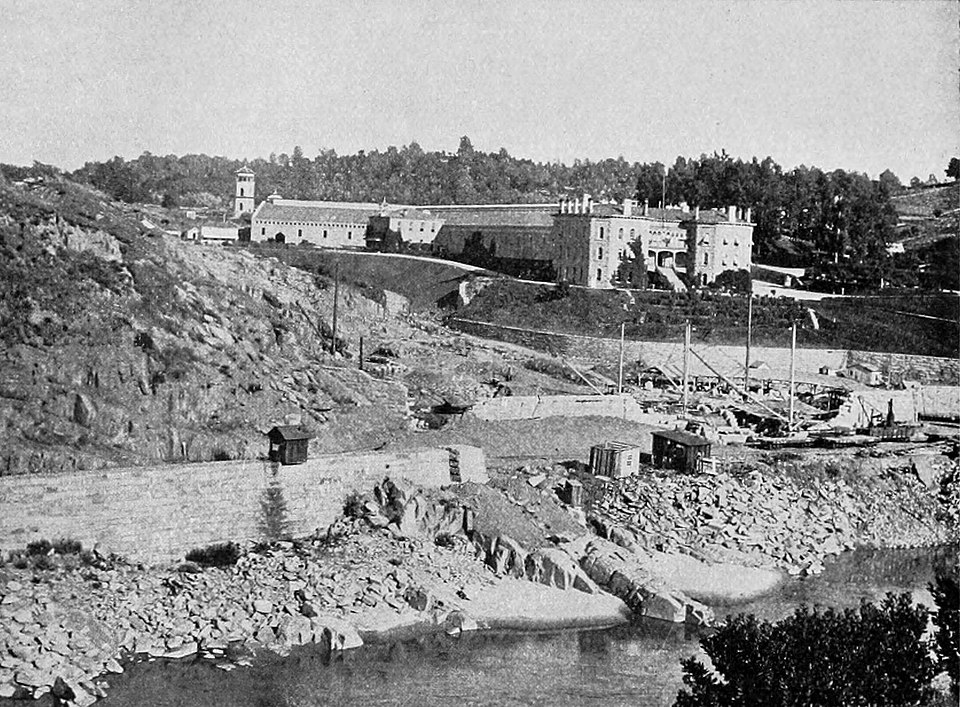

Sentenced to Folsom: The End of the Line

Judge Rodgers sentenced Marion to an indeterminate term in Folsom Prison for second-degree burglary. This meant he could serve anywhere from four years to life, depending on his behavior and progress toward rehabilitation. Folsom was considered the “end of the line,” a prison for the most difficult and dangerous inmates. Its main goals were strict control and punishment, with a focus on hard labor and secure confinement.

Sheriff Clark personally drove Marion to Folsom Prison. Known for treating prisoners with respect, Clark said, “I’ve taken hundreds of men to the penitentiary, and I’ve never used handcuffs. They knew I expected them not to double cross me, and not one ever did.” When he offered to remove Marion’s handcuffs for the ride, Marion declined. “I know that if I’m not handcuffed, I’ll try to escape and I don’t want to double cross you, Bob,” he said. “I don’t want to take any chances on getting shot.”

During the long drive to Folsom, Marion told Clark how he had escaped nearly a year earlier while being taken to the Ventura County jail. When they arrived at the prison, Marion was placed in the infirmary, saying he had heart trouble.

Escape Across the Cold American River

On July 28, 1925, Marion escaped from Folsom Prison by swimming across the American River. He was working with a group of inmates cutting brush when he made his move. The American River, which runs alongside the prison, played a part of several past escape attempts. Fed by snowmelt from the Sierra Nevada, its water stays dangerously cold year-round. Even in July, the icy temperatures, strong currents, and hidden hazards made swimming across it extremely risky. By September, prison officials tightened security at state prison road camps in response to Marion’s escape and several others in recent months. With Marion on the run, law enforcement across Southern California searched for him, and for Dominguez, believing he’d try to find her. But Marion was traveling with a different woman.

On the night of December 11, Marion resurfaced near his hometown of Pomona. During Prohibition, deputies were watching the roads for bootleggers when they stopped a stolen car driven by Marion. With him was a woman named Esperanza Mercado. When told to get out, Marion obeyed, but as soon as he stepped out, he ran, leaving Esperanza behind. Officers caught him and brought him back to the vehicle, but as they began to handcuff him, he broke free again, this time with the handcuffs still attached to one wrist. Inside the car, deputies found over $3,000 worth of stolen goods from homes across the Pomona Valley. The vehicle was stolen from Frank Aguilar in Cucamonga. With Esperanza in custody, police assumed the man with her was her husband, Leo Mercado.

A Man Lying Still in the Hayfield

In late December, a Moorpark woman saw a large car abandoned, nose down in a ditch on the Borchard Ranch near the Dingess Grade. Nearby, she saw a man lying in a hayfield and feared he was dead or had been attacked. She called three part-time deputies, garagemen Art and John Mahan, and local druggist F.W. Wengenroth.

The man lay still, wrapped in a lap robe, overcoat, and mackinaw, with a Winchester .30-30 rifle beside him. As the deputies got closer, he suddenly jumped up and grabbed the gun. They quickly disarmed him and put him in their car to take him into town. One deputy thought he looked familiar, but none of them knew they had just captured Marion—one of Southern California’s most wanted fugitives.

They placed Marion in the back seat alone, while Wengenroth rode on the running board holding the rifle. At first, Marion sat still, but as the car reached the bottom of the grade, going about 35 miles an hour, he suddenly leapt over the door, on the same side as Wengenroth was riding, and tried to escape. Wengenroth struggled with him and hit him on the head several times with the rifle butt, knocking him from the car. Marion hit the ground, landed hard on his head, but jumped up immediately and ran into the brush. Wengenroth fired a shot at him, but Marion disappeared into a steep, narrow ravine. The 1923 Hudson Touring Coach that Marion left behind was riddled with bullet holes, had two sets of license plates, and contained several boxes of ammunition. Authorities later said that if the Moorpark deputies had known who he was, they never would have let their guard down. A posse searched the hills around Conejo and Moorpark. The hunters moved to Malibu after they received a tip that Marion had dinner at a service station near the Malibu Lake Club. The search came up empty. Marion had vanished again.

Seven Bullets Bring Marion Down

Marion was on the run for five and a half months, but on the morning of January 11, 1926, his freedom came to a violent, bloody end. After a desperate chase through the streets of Stockton and a furious exchange of gunfire with police, Marion was shot seven times. Bleeding and broken, he collapsed on a stairwell floor. Hours later, he lay in a hospital bed, under heavy guard and clinging to life.

That day started when Officers J.B. Patton and Elmer Thorpe saw a man standing near a newer-model Ford coupe and stopped to question him. The man, later identified as Marion, gave vague answers and couldn’t explain where the car came from. As the officers went to call for backup, Marion made a break for it.

Thorpe chased him, firing once before his gun jammed. Marion ran into a house on Center Street. Inside, he turned and pressed a pistol into Thorpe’s ribs. The officer dodged just as Marion fired and the bullet missed. Thorpe ran outside and tried to come in from the back, but Marion fired again and missed.

Marion then ran several blocks to a rooming house on South El Dorado Street. More officers had now joined the chase, including Patton, McGlothen, Owen Childs, McHugh, and Werle. As Patton arrived, Marion turned and fired at him from only a few feet away but missed again. He ran inside and took a position at the top of a staircase. Patton and McGlothen followed and took cover at the bottom.

During the gunfight, Patton ran out of bullets and shouted for help. Officer Childs tossed him a loaded revolver, and the battle continued. Marion shouted that he was giving up, but as the officers moved in, he opened fire once more. At that moment, Officers McHugh and Werle entered from the back and rushed him. Marion threw down his empty pistol and collapsed, hit by seven bullets. He had been shot three times in the right leg, twice in the left, and twice across the ankles. All wounds passed clean through, but he was in serious condition. Two bystanders were also hurt during the shootout. One man, 67-year-old Wong Fun was hit by a stray bullet that passed through the upper right part of his lung, while 23-year-old E. Marchetti was shot in the leg. Marchetti’s injury was minor. Remarkably, Wong’s wound, though serious, did little damage as the bullet passed clean through.

A search of the Ford coupe that led to Marion’s arrest turned up stolen items, including men’s and women’s clothing, a camera, sports equipment, and bags. Many of the items came from a burglary at the Upland home of Owen E. Atwood. The car itself was stolen from the garage of a young woman named Ida Vernon. The woman’s father told police his home had been robbed five times in the past two years. When the car was stolen, he had been staying up, expecting someone to try to take it, but fell asleep. He added that the spare tire was stolen from the car only a few days earlier. The car’s odometer showed just 400 miles at the time of theft. In the eight days that Marion had the car, he added on another 2,400 miles.

Clippings Unmask the “Handcuff Fugitive”

Though weak from blood loss and in obvious pain, Marion remained defiant and refused to cooperate with police. He was quickly identified as the escaped convict from Folsom, but officers were puzzled by what they found in his rented room in Stockton: newspaper clippings from Los Angeles and Pomona about the dramatic December escape of the so-called “handcuff fugitive,” a man still believed to be Leo Mercado.

Along with the clippings, police found money order receipts showing that Marion sent money to Esperanza Mercado, who was still held in the San Bernardino County Jail. This discovery sparked a week-long debate; were Marion and Mercado the same man?

The mystery was finally cleared up on January 20, during Esperanza Mercado’s preliminary hearing in Upland. She admitted to lying: the man she was with during the December escape wasn’t her husband Leo, as she claimed, it was Marion. She said she traveled with Marion for some time, and they agreed to use her husband’s name if they ever got caught.

According to Pomona authorities, it was Marion’s vanity, his decision to keep those newspaper clippings, that ultimately gave him away. Without them, they might never have known who the “handcuff fugitive” really was.

Sentenced Back to Folsom

At first, doctors thought Marion might die from his wounds. But as his condition improved, the authorities had to decide where he would face justice. He could be returned to Folsom Prison, from where he had escaped the previous July, or sent to Upland to face burglary and grand larceny charges. In the end, there was little debate; Marion would stand trial in Stockton, where the evidence against him was strongest.

In addition to residential burglary and car theft, Marion faced serious charges for the gunfight with police. On January 14, while still in the hospital, he was formally charged with three counts of assault with a deadly weapon with intent to commit murder for firing at three Stockton officers.

Meanwhile, in Upland, Esperanza Mercado was ordered to stand trial in Superior Court for burglarizing a ranch house near Ontario. Around the same time, Stockton police received a box of cigars and a thank-you note from Atwood, the Upland burglary victim. He praised the officers for recovering most of his stolen items and added that he was “very glad that none of your officers were injured when making the arrest.”

Marion pleaded not guilty, and his trial was postponed until he fully recovered. But in February, The Ventura Weekly Post and Democrat reported that Marion tried and failed to escape from his cell using a crude saw made from an ordinary table knife.

On March 27, 1926, Marion changed his plea to guilty at the urging of his court-appointed attorney, Elmer Forslund. In court, he told Judge C. Miller that he had originally pleaded not guilty only to buy time. He hoped friends would send him musical instruments before he was sent back to prison, believing he wouldn’t be allowed to receive them afterward. Judge Miller sentenced Marion to the term required by law; one to fourteen years and he was returned to Folsom Prison. The following month, San Bernardino County Judge George R. Crane chose not to try Esperanza Mercado for burglary. Instead, he ordered her deported to Mexico. In late 1928, Folsom Prison records show that Marion’s sentence was extended by five years for his 1925 escape.

An Ending Lost to Time

Just as Marion remained elusive during his decade-long crime spree in Southern California, the ending to his story proves just as hard to pin down. State prison records in the California Archives show no trace of Marion after 1928. There’s no record of how long he stayed in prison, or if he was ever released. A thorough search of California newspapers for his name and known aliases turned up nothing about his parole or death. What is clear is that no more burglaries were ever linked to him.

One of the last times Marion’s name appeared in the news was in October 1929. The Ventura County Star reported that Sheriff Clark, speaking to the Ventura Rotary Club, called for stronger cooperation between the public and law enforcement. He used Marion as an example, describing him as “an especially resourceful and dangerous thug” who was finally caught and sent back to prison thanks to that kind of teamwork.

By the end of the 1920s, Ventura County Sheriff’s Department grew, and patrols increased. New tools for identifying criminals and solving crimes helped deal with the rising number of offenders. Laws were passed to increase penalties for robbery and burglary, and courts began handing down tougher sentences. In The Ventura Weekly Post and Democrat, J.L. McKeen blamed weak probation laws and argued jails should be “a place to dread,” where inmates were forced to do hard labor. The days of a burglar like Marion slipping in and out of custody were coming to an end.

Make History!

Support The Museum of Ventura County!

Membership

Join the Museum and you, your family, and guests will enjoy all the special benefits that make being a member of the Museum of Ventura County so worthwhile.

Support

Your donation will help support our online initiatives, keep exhibitions open and evolving, protect collections, and support education programs.

Bibliography

- The Bulletin (Pomona). “Grim Reaper Leads Youth to Jail Cell From Funeral.” January 7, 1917, 8.

- The Bulletin (Pomona). “Marrione is Held to Answer on Charge of Motorcycle Theft.” January 11, 1917, 8.

- The Bulletin (Pomona). “Marrione to Plead Guilty and Seek Probation, Report.” January 12, 1917, 8.

- The Bulletin (Pomona). “Mexican Maid Held as Aide in Over 50 Country Burglaries.” December 14, 1923, 2.

- The Bulletin (Pomona). “Motorcycle Thief Guilty, Begs Freedom.” February 7, 1917, 8.

- The Bulletin (Pomona). “Officers Now Believe Gun Victim Is Burglar; Gives Police Information.” January 13, 1926, 8.

- The Bulletin (Pomona). “Revolver Duel in North Has Echo in South.” April 27, 1926, 7.

- The Bulletin (Pomona). “Stolen Motor to Cost Local Lad Three Years in Prison.” February 21, 1917, 1.

- The Bulletin (Pomona). “Stolen Motorcycle is Reported Seen: Again Disappears.” July 16, 1916, 12.

- The Bulletin (Pomona). “Trial of Woman in Alta Loma Burglary Case, Said Doubtful.” January 4, 1924, 2.

- The Bulletin (Pomona). “Woman Betrays Identity of Wounded Bandit.” January 21, 1926, 9.

- Contra Costa Times (Walnut Creek). “California Prison Inmates Increase.” December 27, 1928, 1.

- “Criminal Identification: The Bertillon System.” Cleveland Police Museum. Last modified April 7, 2020. https://www.clevelandpolicemuseum.org/historical/criminal-identification-the-bertillion-system/.

- The Daily Report (Ontario). “Clippings, Money Orders, Identify West End Bandit.” January 12, 1926, 1.

- The Daily Report (Ontario). “Hold Girl for Raid on Store of Alta Loman.” November 20, 1923, 7.

- The Daily Report (Ontario). “May Send Woman Who Aided Thief Back to Mexico.” April 26, 1926, 5.

- The Daily Report (Ontario). “Sawyer Confirms Mercado Capture After Gun Fight.” January 15, 1926, 5.

- The Long Beach Telegram and The Long Beach Daily News. “Couple Charged With Robberies.” November 9, 1923, 31.

- Los Angeles Evening Post-Record. “Swims to Freedom.” August 1, 1925, 1.

- The Los Angeles Times. “Captured Thug Evades Officers.” December 30, 1925, 28.

- Morning Free Press (Ventura). “Attempts to Hang Himself at County Jail.” November 22, 1923, 1.

- Morning Free Press (Ventura). “Find Burglar’s Cache.” January 20, 1923, 1.

- Morning Free Press (Ventura). “Juan Marion Pleads Guilty.” January 3, 1924, 1.

- Morning Free Press (Ventura). “Marion Hearing is Held Here This Afternoon.” November 14, 1923, 1.

- Morning Free Press (Ventura). “Marion Pleads Not Guilty.” December 5, 1923, 1.

- Morning Free Press (Ventura). “Woman is Held for High Court.” December 12, 1923, 1.

- Morning Tribune (Los Angeles). “Man Hunted Months Caught at Funeral.” January 7, 1917, 10.

- Morning Tribune (Los Angeles). “Suspected Boy Seeks to Return to Pomona.” November 27, 1914, 9.

- The Ontario Record. “Accused Burglar Keeps Pledge to Return His Loot.” January 7, 1924, 1.

- The Orange County Plain Dealer (Anaheim). “Lodged in Jail.” November 9, 1923, 1.

- Oxnard Press-Courier. “479 New Laws for California.” June 30, 1923, 1.

- Oxnard Press-Courier. “Bandits Who Terrorized Simi Valley Captured in Shack at Hueneme; 1 Desperado Escapes.” January 20, 1923, 1.

- Oxnard Press-Courier. “Believe Escaped Man Caught in Quicksand.” February 2, 1923, 1.

- Oxnard Press-Courier. “Chloroform Burglars Menace Santa Barbara.” March 14, 1923, 1.

- Oxnard Press-Courier. “Juan Marion Desperate Man Still at Large.” December 29, 1925, 1.

- Oxnard Press-Courier. “Marion Bound Over to Superior Court; World is Beautiful He Says.” November 15, 1923, 1.

- Oxnard Press-Courier. “Marion In Jail; Tells Sheriff of Robberies Held on $10,000 Bond.” November 13, 1923, 1.

- Oxnard Press-Courier. “Robbers’ Lair Found In Secluded Canyon By Santa Susana Pass.” November 28, 1922, 1.

- Pasadena Star-News. “Accuse Couple of Wholesale Thefts.” November 9, 1923, 6.

- Pomona Morning Times. “2 Charges Against Him.” May 11, 1911, 1.

- Pomona Morning Times. “Another Crime Laid to Marrione.” May 23, 1911, 1.

- Pomona Morning Times. “Candidate for Penitentiary.” May 17, 1911, 1.

- Progress-Bulletin (Pomona). “Drunken Row: One Badly Cut.” May 1911, 1.

- Progress-Bulletin (Pomona). “Held to Answer On Two Charges.” May 10, 1911, 2.

- Progress-Bulletin (Pomona). “Insist Fugitive is Wanted Man.” January 13, 1926, 3.

- Progress-Bulletin (Pomona). “Marrione Enters Plea on Tuesday.” February 5, 1917, 8.

- Progress-Bulletin (Pomona). “Marrione Held in Blatz Bike Case.” January 10, 1917, 8.

- Progress-Bulletin (Pomona). “Marrione Makes Escape.” May 16, 1911, 3.

- Progress-Bulletin (Pomona). “Marrione Pleads Guilty.” February 7, 1917, 7.

- Progress-Bulletin (Pomona). “May Be Blatz Machine.” July 26, 1916, 5.

- Progress-Bulletin (Pomona). “Mercado’s Accomplice Confesses.” January 20, 1926, 1.

- Progress-Bulletin (Pomona). “Motor Bike Thief Gets Three Years.” February 21, 1917, 8.

- Progress-Bulletin (Pomona). “Motorcycle is Stolen From Boy.” July 15, 1916, 6.

- Progress-Bulletin (Pomona). “Sorry Boy Now Ready to Return.” November 25, 1925, 7.

- Progress-Bulletin (Pomona). “Stolen Motorcycle Located.” May 22, 1911, 4.

- Progress-Bulletin (Pomona). “Voice From The Dead Calls Young Man Into Clutches Of Law Here.” January 6, 1917, 4.

- Progress-Bulletin (Pomona). “Weaving Net of Evidence Today.” January 8, 1917, 8.

- Redlands Daily Facts. “Repeated Burglar to Face Charge of Assault.” January 13, 1926, 12.

- Redlands Daily Facts. “Upland Bandit Believed Shot.” January 15, 1926, 11.

- The Sacramento Bee. “3 Wounded When Stockton Police Battle Mexican.” January 11, 1926, 1.

- The Sacramento Union. “Man Shot By Stockton Police Has Prison Record.” January 12, 1926, 16.

- The San Bernardino County Sun. “Couple Held To Answer Before Superior Court.” December 12, 1923, 9.

- The San Bernardino County Sun. “New Theory on Suspect Advanced.” January 16, 1926, 14.

- The San Bernardino County Sun. “Sheriff Will Try to Bring Bandit Here.” November 11, 1923, 11.

- The San Bernardino County Sun. “Upland Thief is Shot Seven Times, Caught.” January 12, 1926, 11.

- “Sharp & Savvy: The Clark Brothers.” Ojai History – Sharing the History of the Ojai Valley. Accessed July 23, 2025. https://ojaihistory.com/sharp-savvy-the-clark-brothers/.

- Simi Valley Star. “Burglars Captured and Loot Recovered.” January 25, 1923, 1.

- Simi Valley Star. “Home Robbed at Santa Susana.” January 18, 1923, 4.

- Simi Valley Star. “Insanity is Now Feigned by Marion.” November 1923, 1.

- Simi Valley Star. “Juan Marion Taken After Being Wounded.” January 28, 1926, 1.

- Simi Valley Star. “Juan Marion Tells How He Escaped.” January 17, 1924, 2.

- Simi Valley Star. “Juan Marion, Captured and Escaped Here, Now Believed Hiding in Malibu Mountains.” December 31, 1925, 1.

- Simi Valley Star. “Marion Sentenced to Term In Folsom.” January 10, 1924, 1.

- Simi Valley Star. “Marion as Witness.” December 13, 1923, 1.

- Simi Valley Star. “Sheriff Clark Captures Artful Dodger Marion.” November 15, 1923, 8.

- Stockton Evening and Sunday Record. “Assault to Kill Complaint Filed Against Mexican.” January 13, 1926, 11.

- Stockton Evening and Sunday Record. “Box of Cigars Sent Policemen.” January 27, 1926, 5.

- Stockton Evening and Sunday Record. “Ex-Convict Shot in Police Battle Involves Others.” January 12, 1926, 11.

- Stockton Evening and Sunday Record. “Gun Battler Is Sent to Folsom.” March 27, 1926, 9.

- Stockton Evening and Sunday Record. “Mexican Riddled With Bullets By Two Policemen.” January 11, 1926, 7.

- Stockton Independent. “Marrione is Charged With Kill Intent.” January 14, 1926.

- Ventura County Star. “Counties Join in Bandit Hunt.” December 30, 1925, 1.

- Ventura County Star. “Rumor Juan Marion Now In Our Hills.” November 28, 1925, 1.

- Ventura County Star. “Sheriff Reviews Famous Man Hunt.” October 30, 1929, 1.

- Ventura County Star. “Stricter Rules in Prison Road Camps.” September 2, 1925, 3.

- Ventura Daily Post. “Cache Of Goods From Marion Thefts Is Uncovered.” January 6, 1924, 1.

- Ventura Daily Post. “Marion Tells How He Made Getaway.” January 12, 1924, 1.

- The Ventura Weekly Post and Democrat. “Bandit’s Hand in Many Burglaries.” November 16, 1923, 2.

- The Ventura Weekly Post and Democrat. “Bound Over on Burglary Charge.” December 14, 1923, 8.

- The Ventura Weekly Post and Democrat. “Bullet-Pierced Automobile Cause Of Police Inquiry.” January 8, 1926, 6.

- The Ventura Weekly Post and Democrat. “Burglar Sends Woman $200 And He Retains $18.” November 23, 1923, 3.

- The Ventura Weekly Post and Democrat. “Communication.” February 23, 1923, 4.

- The Ventura Weekly Post and Democrat. “Gives Up Pretending to be Insane.” December 7, 1923, 3.

- The Ventura Weekly Post and Democrat. “Juan Marion Fox Robber Escapes from Prison at Folsom.” July 31, 1925, 1.

- The Ventura Weekly Post and Democrat. “Juan Marion Shot Down During Robbery.” January 29, 1926, 1.

- The Ventura Weekly Post and Democrat. “Marion Makes Escape Attempt.” February 5, 1926, 3.

- The Ventura Weekly Post and Democrat . “Marion Makes Good His Escape.” January 1, 1926, 1.

- The Ventura Weekly Post and Democrat. “Marion Makes Real or Feigned Attempt to Go By Rope Route.” November 23, 192, 1.

- The Ventura Weekly Post and Democrat. “Marion’s Bond is Fixed at $10,000.” November 16, 1923, 7.

- The Ventura Weekly Post and Democrat. “Noted Bandit Feigns Insanity Here.” November 23, 1923, 4.

- The Ventura Weekly Post and Democrat. “Officers Comb Hills for Man Believed to be Juan Marion.” January 1, 1926, 7.

- The Ventura Weekly Post and Democrat. “Thieves Steal Stuff at Crinklaw Home.” January 19, 1923, 3.

- Visalia Daily Times. “Former Convict Confesses to Burglaries.” January 12, 1926, 5.