by Library Docent Volunteer Andy Ludlum

Content Warning: This blog post concerns politics during and after the American Civil War. It quotes contemporary newspapers to illustrate the political climate at that time. Some of these quotations include terminology that is outdated and may be offensive to some readers. Reader discretion is advised.

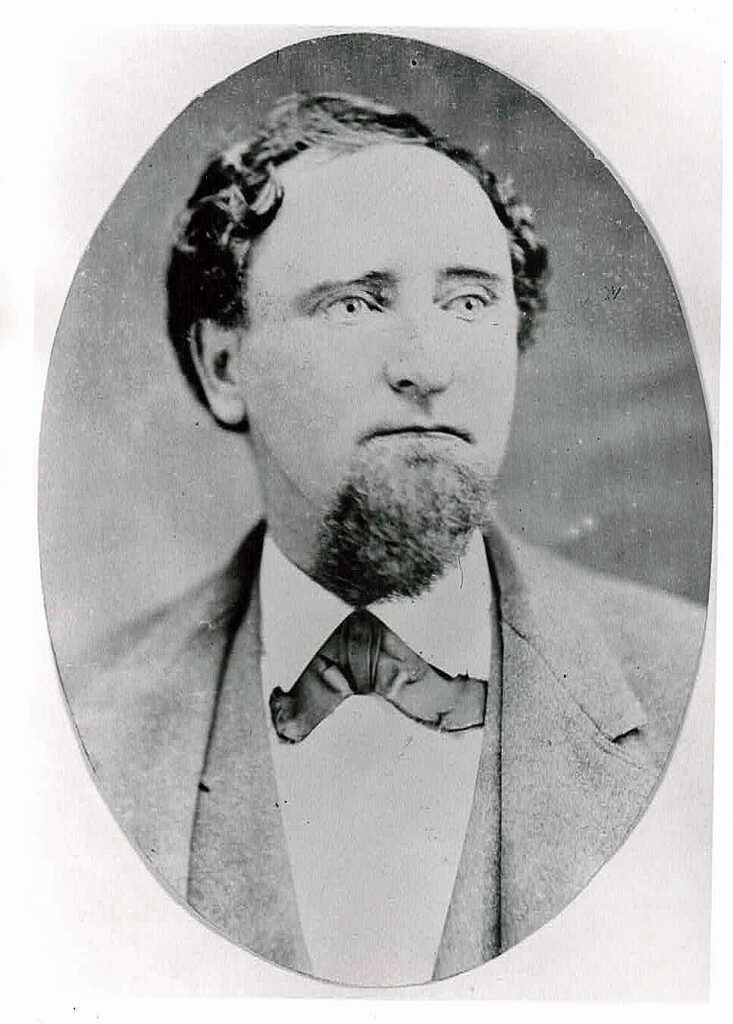

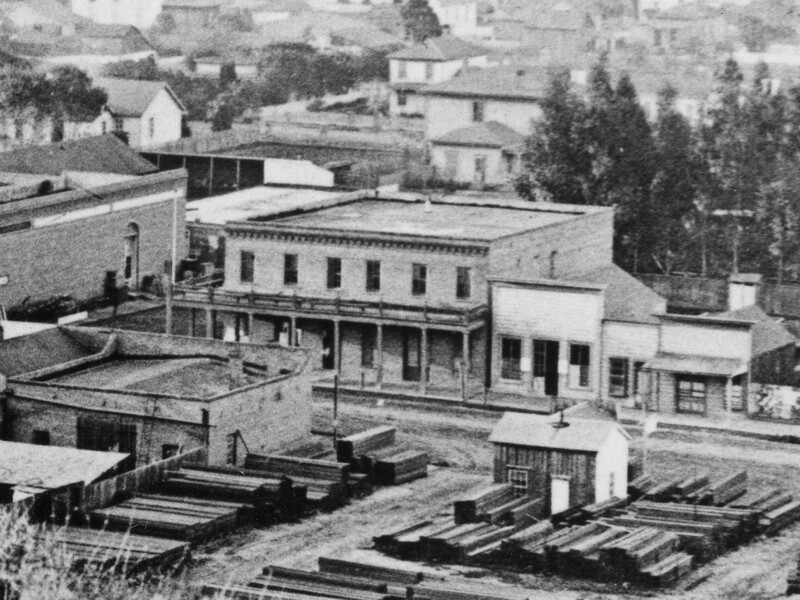

Walter Chaffee spent several nights cradling a loaded shotgun, guarding the American flag that flew on a liberty pole in front of his dry goods store at the corner of Palm and Main in San Buenaventura. During the Civil War, Chaffee had proudly kept the U.S. flag flying day and night, but vandals who didn’t support the Union kept stealing it. News of President Abraham Lincoln’s assassination on April 14, 1865, took days to reach the small mission town. Chaffee’s flag was said to be the only one south of San Jose flown at half-staff to honor the fallen president.

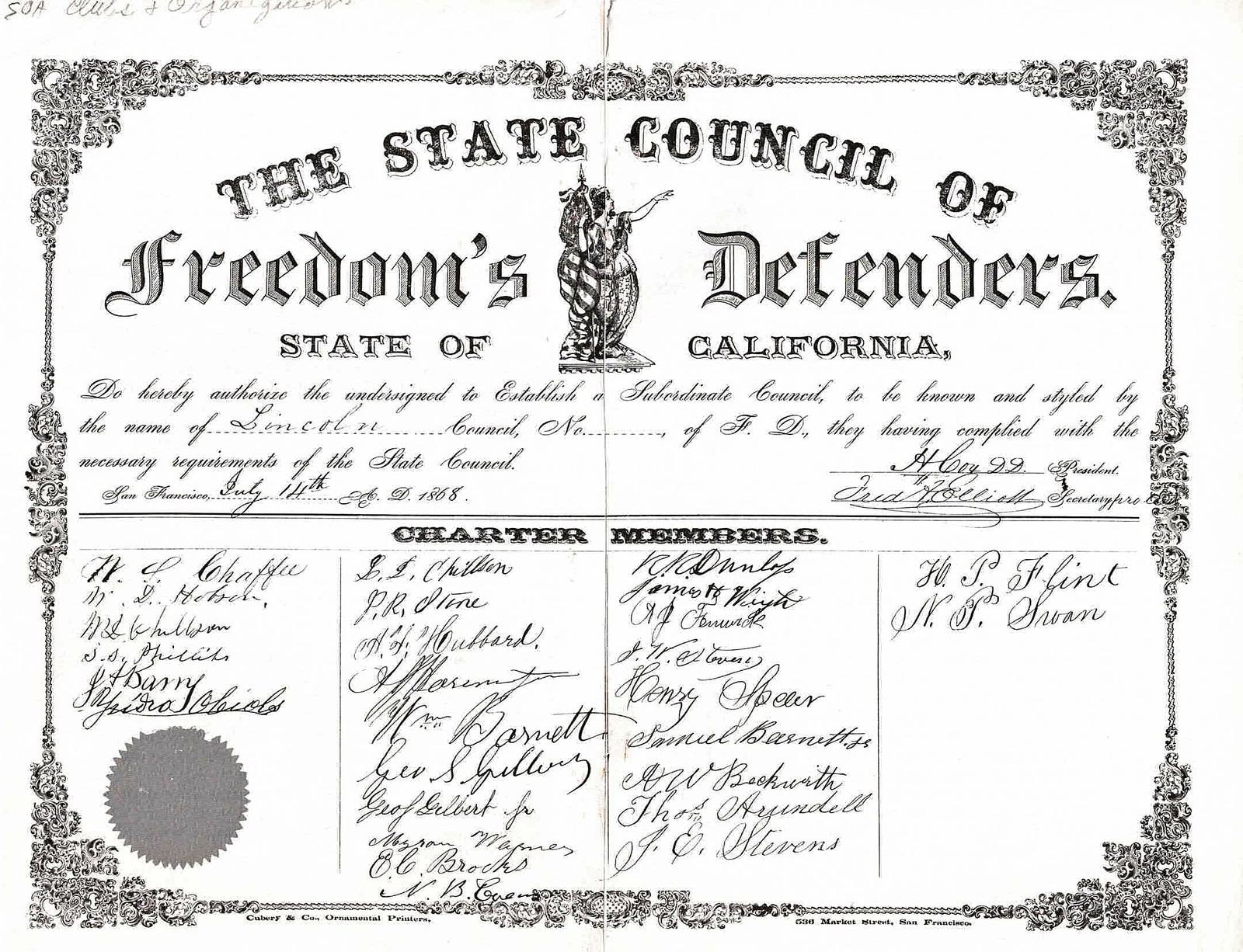

Being pro-Union or Republican in Southern California during the Civil War and the chaotic years that followed was risky. Chaffee and 26 others who shared his views met secretly in a small adobe next to Hill School. Just months before the first presidential election after Lincoln’s assassination, they revealed themselves and signed a charter to form the Lincoln Council of Freedom’s Defenders in San Buenaventura.

A Free State in Name Only

California entered the Union in 1850 with a state constitution that banned slavery. Southern members of Congress opposed “free” statehood, but Northern lawmakers supported it because of California’s fast-growing population and gold wealth. When gold was found in 1848, many Southern slaveholders joined the gold rush. In the following years, they brought around 1,500 enslaved African Americans to California.

Slaveholders and their supporters held an outsized number of top government positions in California during the 1850s. On major political issues, the state often sided with the South. One observer even said California was “as intensely Southern as Mississippi.” Although Democrats were a minority across the state, they were the majority in Southern California and Tulare County, and had a strong presence in San Joaquin, Santa Clara, Monterey, and San Francisco counties.

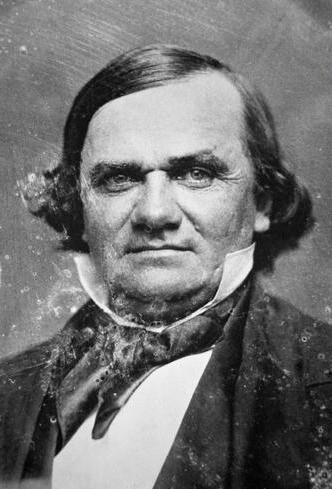

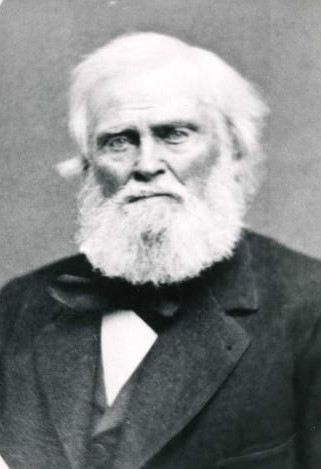

California’s first elected governor, Peter Hardeman Burnett, was a former slaveholder who strongly supported making the American West whites-only. After moving to Oregon in 1843, he helped pass a law that let white settlers keep enslaved people for three years, then forced them to leave the territory. If they didn’t leave, they would be whipped. The law was considered too harsh and was never enforced; voters repealed it in 1845. Burnett moved to California during the Gold Rush and was elected governor in 1849. He then tried—but failed—to pass laws banning Black people from living in the state. Burnett also supported the removal of California’s Indigenous people, saying he believed there would be a “war of extermination” until they were wiped out. He was also one of the first to push for keeping Chinese immigrant workers out of California. After his time as governor, he supported the federal Chinese Exclusion Act.

During the Gold Rush, California ignored the use of slave labor and continued to enforce fugitive slave laws until the mid-1860s. The state’s 1849 constitution only allowed adult white men to vote. By 1860, just six northern states had given African Americans the right to vote.

Slavery Defined the 1860 Election

The issue of slavery deeply divided the country during the 1860 presidential election. There were four main candidates: Abraham Lincoln, Stephen A. Douglas, John C. Breckinridge, and John Bell. Lincoln, the Republican, opposed expanding slavery into new territories. Breckinridge, the Southern Democrat, wanted to protect and grow slavery. Douglas, the Northern Democrat, supported popular sovereignty—letting each state or territory decide on slavery. Bell, from the Constitutional Union Party, tried to keep the country united but avoided taking a clear position on slavery. Lincoln won the election without winning any Southern states. In California, the Democratic vote was split between Douglas, Breckinridge, and Bell, allowing Lincoln to win the state by a narrow margin, even though he didn’t get a majority of the popular vote.

Breckinridge won in every Southern California county except two, including Santa Barbara County. (Ventura County was still part of Santa Barbara County at the time and wouldn’t become separate until 1873.) According to the Sacramento Daily Union, in Santa Barbara County, Breckinridge got 123 votes (about 26%), Douglas got 305 (about 64%), Lincoln received 46 (just under 10%), and Bell got none.

In 1860, California was growing rapidly. Between 1847 and the federal census in 1860, its population nearly tripled to 308,000. Even with this growth, the state remained isolated from the rest of the country because there was no railroad connecting it to the East. The Transcontinental Railroad wouldn’t be completed until 1869.

In the 1850s, people in Southern California, frustrated by unfair taxes and land laws, tried three times to separate from Northern California and form their own state or territory. Some even wanted Southern California to become a new slave state. They believed that by leaving California, they could drop the state’s Constitution, legalize slavery, and attract slaveholders moving west. When the Civil War began in 1861, there were several secession scares in the West. In San Francisco, some secessionists tried to break away California and Oregon from the Union, but they failed. In the end, all these efforts were stopped by the presence of federal troops.

San Buenaventura Union Supporters Meet in Secret

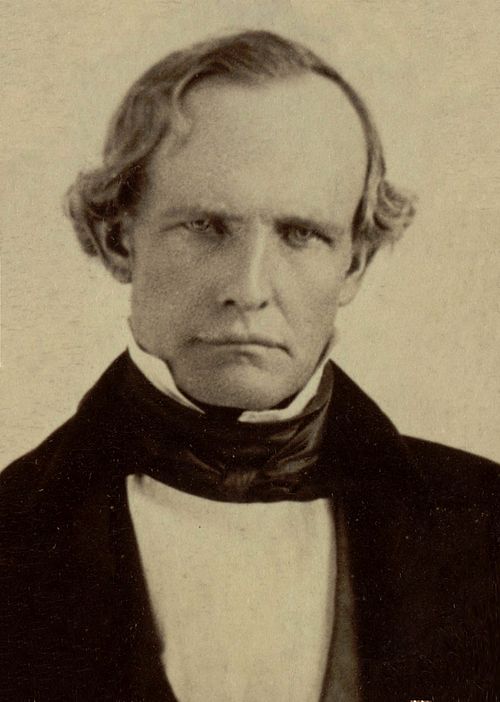

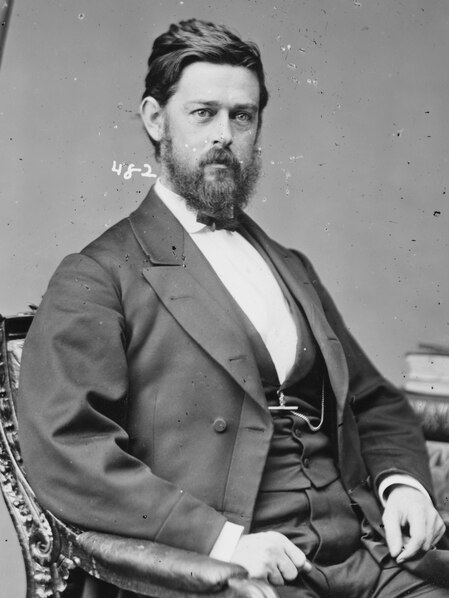

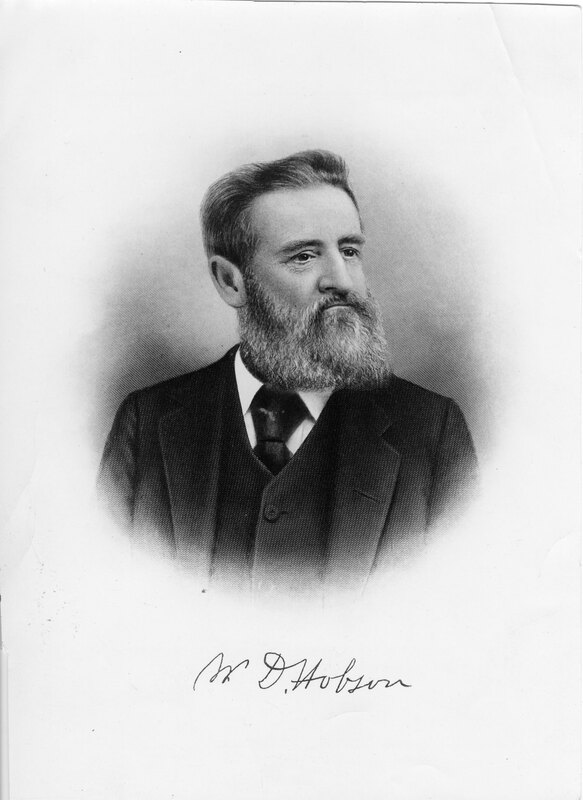

The Union supporters began meeting in the old adobe guardhouse above the San Buenaventura Mission during the final years of the Civil War. As Anna Flint recalled in a 1984 interview, her father-in-law, H. P. Flint, told her, “[Y]ou couldn’t be a Republican… at that time.” Flint and Chaffee had arrived in Ventura in 1861, a town with only three other men who’d migrated from the East. Two of them, W. D. Hobson and George S. Gilbert, Sr., also joined the early Republican meetings. According to historian Sol Sheridan, members used secret signs, grips, and passwords to enter the meetings. Sheridan noted that people were “Republicans – or Democrats – in the dark,” since openly declaring political views was dangerous and only safe in carefully chosen company. Other early Ventura pioneers who joined the Republican cause included Samuel Barnett Sr., Andrew Harrington, William Barnett, and Ysidro Obiols, a Spaniard who came to California during the gold rush.

The 13th Amendment, which abolished slavery, was passed by the U.S. Senate on April 8, 1864, and by the House of Representatives on January 31, 1865. Throughout the war, the California legislature supported the Union and approved the amendment, which was ratified by enough states on December 6, 1865.

After Lincoln was assassinated in April 1865, his successor, Andrew Johnson, took on the task of rebuilding the Union. A War Democrat from Tennessee, Johnson had been Lincoln’s running mate in 1864 on the National Union ticket, a coalition aimed at uniting Republicans and War Democrats. Johnson strongly believed in states’ rights and took a lenient approach toward white Southerners in his Reconstruction plan.

Many of California’s leaders held onto a nostalgic view of the Old South. Captain William Simms Moss, raised on a wealthy Southern plantation, was the editor of the state’s leading Democratic newspaper. He openly mourned the end of slavery, calling it the “negro birthright,” and argued that African Americans were “incapable of self-government” and “unfit to be free.” Moss’s paper, the San Francisco Examiner, was founded in 1863 as the Democratic Press, a pro-Confederacy, pro-slavery, and pro-Democratic Party publication that opposed Abraham Lincoln. After Lincoln’s assassination in 1865, the paper’s offices were destroyed by a mob, and by June, it was rebranded as the Daily Examiner. Moss’s Democratic Party took control in the September 1867 gubernatorial election, promising to maintain white rule in California.

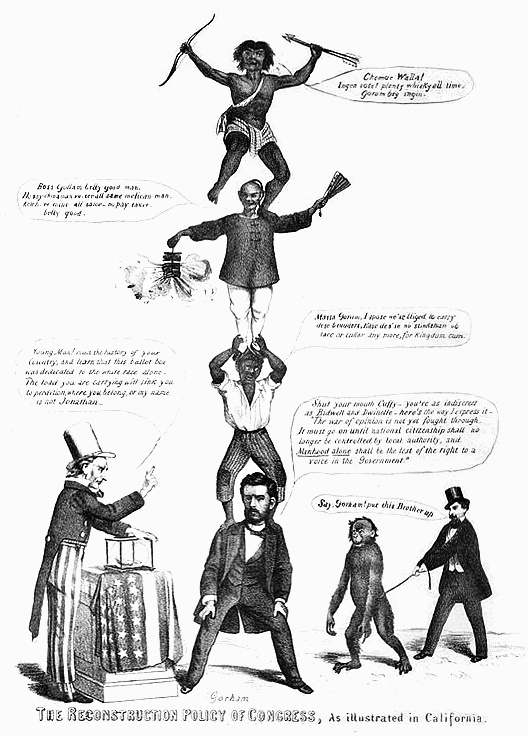

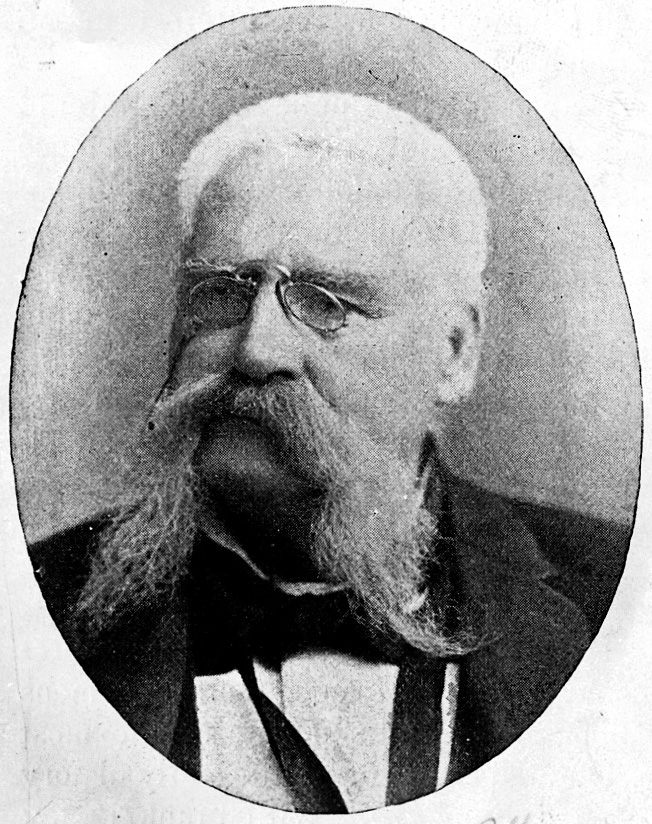

White Supremacist Becomes Governor in 1867

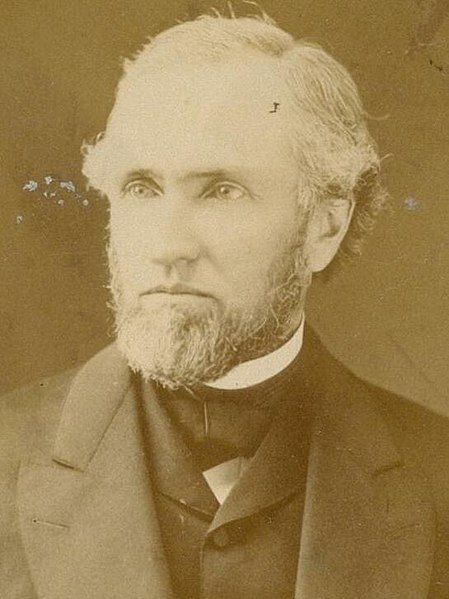

On the ballot was Henry Haight, a former Republican state chair who left the party after Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation. He ran as a Democrat against George Gorham, a newspaper editor and writer. Haight strongly opposed Reconstruction, claiming it would put white Americans “under the heel of negroes” and warning that allowing all men to vote could lead to Chinese immigrants voting in California. He described the Chinese as “pagans,” “serfs,” and part of a “servile, effeminate and inferior race,” arguing they could be easily controlled by their railroad employers. At the time, there were ten times more Chinese immigrants in California than African Americans, and Democrats – mainly Irish and German immigrants – used anti-Chinese sentiment to rally support. Gorham struggled politically due to his ties to the Central Pacific Railroad, but his biggest weakness was his support for Chinese workers and his belief that the word “white” should be removed from naturalization laws. In a landslide victory, Californians elected Haight, who beat Gorham by 9,000 votes and helped sweep the entire Democratic ticket into office.

California as a “Cornucopia for Racists”

California’s labor system in the 1860s relied heavily on Chinese and Mexican contract workers, as well as Native Americans, creating what one historian called “a cornucopia for racists.” During this time, local Ku Klux Klan groups began forming in the state. These groups were involved in violent attacks, mainly targeting Chinese immigrants and their white employers, but they also sometimes threatened Republican politicians and journalists who supported civil rights reforms.

In the 1860s, San Buenaventura was almost entirely white. The 1860 census recorded 628 people in Santa Barbara County, with 304 being white males. There were no “Free Colored”, or “Asiatic” residents listed in the entire county. When Mexican-owned ranchos were divided and sold to small farmers and fruit growers, the area saw a small population boom as settlers from the South and East arrived looking for affordable land. By the 1870 census, San Buenaventura’s population had nearly quadrupled to 1,600. Still, there were only five “Colored,” 14 “Chinese,” and 78 “Indian” residents—and none of them had voting rights at the time. Historian E. M. Sheridan wrote that, after Lincoln’s assassination, political tensions were intense and that “political differences of men were charged with a bitterness of which people [today] have little conception.” Seventeen of the 27 men who signed the San Buenaventura Freedom’s Defenders charter arrived in town during these turbulent years.

San Buenaventura First Hears of the Freedom’s Defenders

In the 1860s, San Francisco was by far the most important city in California. Its population grew rapidly after the Gold Rush, and by 1870, it became the first West Coast city to rank among the 10 largest cities in the U.S. In 1868, San Francisco made up 21% of the entire population of California, Oregon, and Washington combined. The city had a lively and sometimes rowdy political scene, which was closely followed by newspapers across the state. Santa Barbara didn’t have a newspaper until the Santa Barbara News-Press was founded in 1868. Ventura’s first newspaper, The Ventura Signal, didn’t start publishing until April 1871.

People in San Buenaventura, like much of California, likely first heard about the rise of the Freedom’s Defenders in 1867 through newspaper reports covering San Francisco politics. In September, it was reported that the Grant Club – supporters of Lincoln’s National Union Party – had renamed itself the Freedom’s Defenders. The change appeared to be a reaction to the party’s heavy losses in that year’s gubernatorial election. The group’s platform, signed by Major Jack Stratman, said meetings were only open to “the initiated”—any U.S. citizen who was committed to supporting the National Union Party’s candidates and firmly believed in the party’s principles. The San Francisco Examiner, a pro-Democratic paper, was openly hostile to the group. It promised to keep Democrats informed about “the movements of the enemy,” mocking the group as a secret society. The paper claimed they were “afraid to avow their doctrines” publicly, accusing them of meeting in “dirty dens and obscure holes” and using secret handshakes and passwords to blindly control their followers.

The founding resolutions of the Freedom’s Defenders stated that any hostility toward Southerners ended when they stopped fighting. The group’s main goal was to fully restore the Southern states to the Union. However, they insisted that, before that could happen, the Southern states had to completely obey the laws passed by Congress to rebuild their governments.

Another resolution stated that the United States is a nation where every person has the right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. It called America a refuge for the oppressed, with no group having the right to dominate or exclude another. It added that anyone who tries to ignore its laws or deny equal rights isn’t worthy of being called an American citizen. The San Francisco Examiner interpreted this to mean that the Freedom’s Defenders believed Chinese immigrants should have the same rights as European immigrants. However, the group denied supporting Chinese voting rights. They said claims that they backed Chinese suffrage were “shameless lies” spread by political opponents to stir up prejudice—an approach that had worked well for Democrats in the 1867 election.

By early 1868, as the presidential election approached, the Freedom’s Defenders had set up a state council and began forming local branches in major cities, towns, and mining camps – anywhere there were enough loyal supporters dedicated to the Union cause to keep the group going.

The Freedom’s Defenders unanimously backed General Ulysses S. Grant as their top choice for president, but said they would support whoever the national Republican Party officially nominated at its convention in Chicago that May, provided the candidate was “qualified and worthy.” Even before Grant was formally nominated, the San Francisco Examiner launched attacks against him. The paper mocked his cautious support for African American voting rights, claiming it didn’t show a “sufficiently ardent love for the Negro to suit the chiefs of the African party,” its derisive nickname for the Republican Party. It pointed to Frederick Douglass’s Appeal to Congress for Impartial Suffrage as proof that some Republicans were unhappy with Grant. While Grant’s stance on voting rights was still developing and not always as strong as activists hoped, Douglass’s message was directed at Congress—not Grant—urging lawmakers to pass a constitutional amendment granting Black men the right to vote.

Andrew Johnson is Impeached

In early 1868, President Johnson’s conflict with Congress reached a breaking point. Although he required former Confederate states to ratify the 13th Amendment and pledge loyalty to the Union, he mostly let them rebuild their governments as they saw fit. Johnson vetoed the Civil Rights Act of 1866, which was meant to strengthen the 13th Amendment and protect the rights of newly freed enslaved people. Congress overrode his veto, but the fight between Johnson and the Republican-controlled Congress over how to handle Reconstruction continued to grow more intense.

The 14th Amendment, passed by Congress in 1866, was still being voted on by the states. It granted citizenship to all people “born or naturalized in the United States,” including former slaves, and promised “equal protection of the laws” to all citizens. The San Francisco Examiner criticized Congress, calling them “despots” trying to “negroize” the Southern states. The paper claimed that with the help of Black voters, Congress aimed to use the South’s electoral votes to overpower the majority in the North, West, and Central states. California lawmakers chose to let the amendment die in committee.

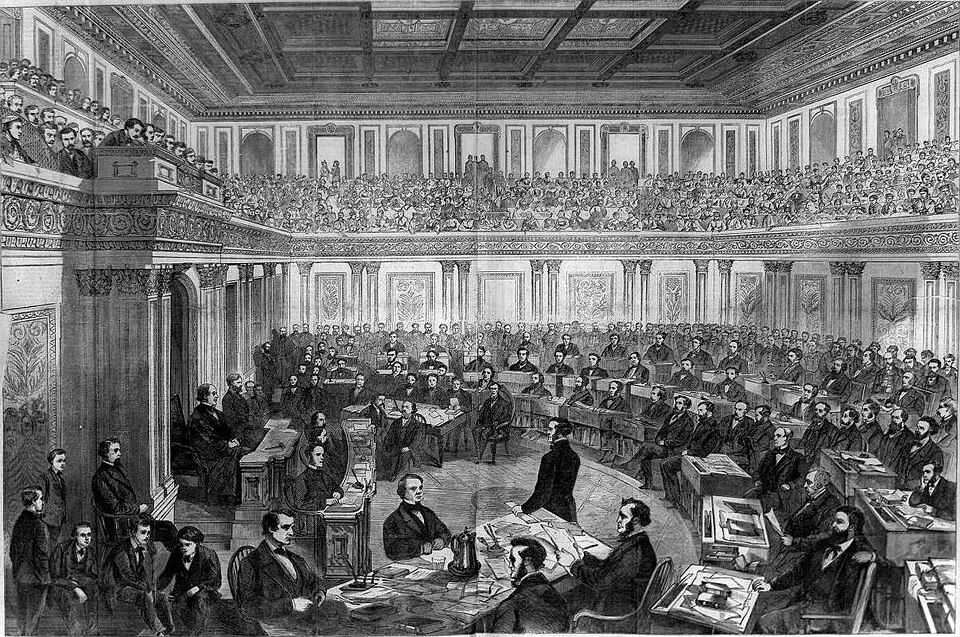

In February 1868, the House voted to impeach President Johnson. While his handling of Reconstruction played a role, the main reason for his impeachment was his violation of the Tenure of Office Act. This law limited the president’s power to remove officials without Senate approval. Johnson had fired Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton, a Lincoln appointee and ally of the Radical Republicans. The San Francisco Chronicle reported that the State Council of the Freedom’s Defenders sent a telegram to the Speaker of the House, saying that they and “the loyal men of California” had passed a resolution declaring that the “President deserves to be impeached and removed from office.” Meanwhile, the San Francisco Examiner criticized the impeachment, claiming Johnson was being punished for “daring to support the laws” and challenging what he saw as clear violations of the Constitution. In late May, Johnson narrowly avoided removal from office by just one vote in his Senate trial. Fifteen days later, without California’s approval, the 14th Amendment was ratified by the states.

Freedom’s Defenders Chapters Pop Up Across the State

The Freedom’s Defenders quickly expanded their organization. Their goal was to unite all Union supporters in California under a common platform. Newspapers in Sacramento and other cities published detailed reports on the group’s gatherings, where 500 to 600 men would listen to political speeches, endorse Grant for president, and pledge to return for monthly meetings, ending with “three cheers for Grant.” By April 1868, the movement had spread beyond major cities like San Francisco and Sacramento, with new chapters forming in places like Stockton, Petaluma, and Marysville.

The San Francisco Examiner criticized the Freedom’s Defenders, calling them a “treasonable faction” of a “plunder-league” led by a radical Congress that aimed to control white voters in the North with the votes of Black Southerners. The paper urged Democrats to organize and distribute materials to counter the “falsehoods and misrepresentations” being spread by the Freedom’s Defenders. Meanwhile, the San Francisco Chronicle, which was more sympathetic to the Freedom’s Defenders, questioned why Democrats were so opposed to them, asking, “Is there anything in the Democratic creed that makes freedom so objectionable?”

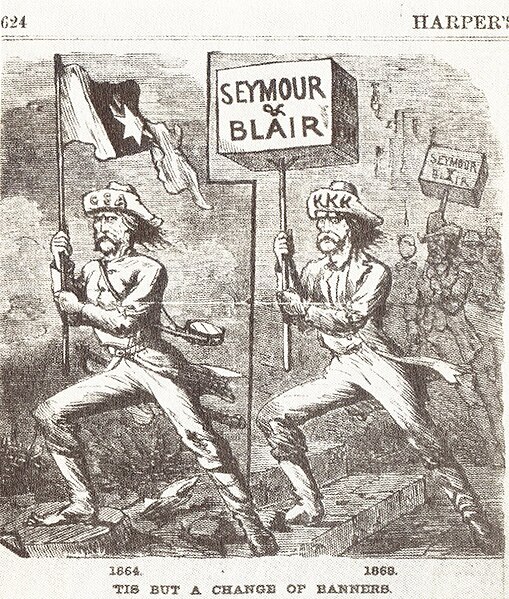

Critics in Democrat-leaning newspapers questioned whether groups like the Freedom’s Defenders and the Grand Army of the Republic, a fraternal group for Union veterans, were “dangerous to the country’s liberties.” Supporters of these groups argued they were simply political clubs for Union party members in California. They pointed out the inconsistency of Democrats, who didn’t criticize their own historical ties to the Ku Klux Klan and the Knights of the Golden Circle—pro-slavery, secretive organizations that had supported secession and aimed to expand slavery into Latin America. The San Francisco Examiner dismissed the accusations, claiming, “We know nothing about the Ku-Klux or any other secret political organization. The old Democratic party is good enough for us. Its actions are open and we’re not afraid to face the light.” The paper then mocked the Freedom’s Defenders, suggesting the Klan was as “credible and respectable” as the “hungry leagues of pap-patriots” making up the organization.

The Democrats held their state convention on April 29 in San Francisco, where delegates chose Lieutenant Governor William Holden as the temporary chairman. Holden was elected during the Democratic sweep the previous September. At the convention, he reportedly lashed out at Congress, the Freedom’s Defenders, and the Grand Army of the Republic. The Nevada City Daily Miner-Transcript responded by saying Holden’s anger was predictable, noting that the Grand Army of the Republic was made up of Union soldiers who defeated the Confederacy, Congress wasn’t controlled by Democrats, and the Freedom’s Defenders were loyal to the Union—”plenty of reason,” the paper said, for Democrats to be upset. The Democratic national convention took place a few months later, in July, in New York City.

Meanwhile, the Sacramento Bee reported that Major Stratman had been selected as a delegate to the Republican National Convention in Chicago that May. The paper praised Stratman as “one of the ablest leaders” of the Republican Party in California, crediting him with organizing the Freedom’s Defenders – a group it said was essential to the party’s strength in the state.

Mixed Message from Some Freedom’s Defenders

From their headquarters in San Francisco, the Freedom’s Defenders sent representatives across California during the spring and summer of 1868. One of them, former State Senator Rollin Gaskill, traveled through Trinity and other northern counties, helping to set up new chapters. By late May, a chapter had been established in the farming town of Danville, leaving only two precincts in Contra Costa County without a local group. Another frequent speaker at Freedom’s Defenders meetings was former state Attorney General Frank M. Pixley, a Republican running for Congress in California’s First District. His remarks on voting rights for former slaves raised eyebrows. According to the Sonora Union Democrat, Pixley told a meeting that “Republicans, as a party, do not advocate the immediate and indiscriminate voting of colored men, without regard to education or fitness.” Pixley also strongly opposed Chinese immigration and voting rights for Chinese people—a stance that was widely supported in California at the time.

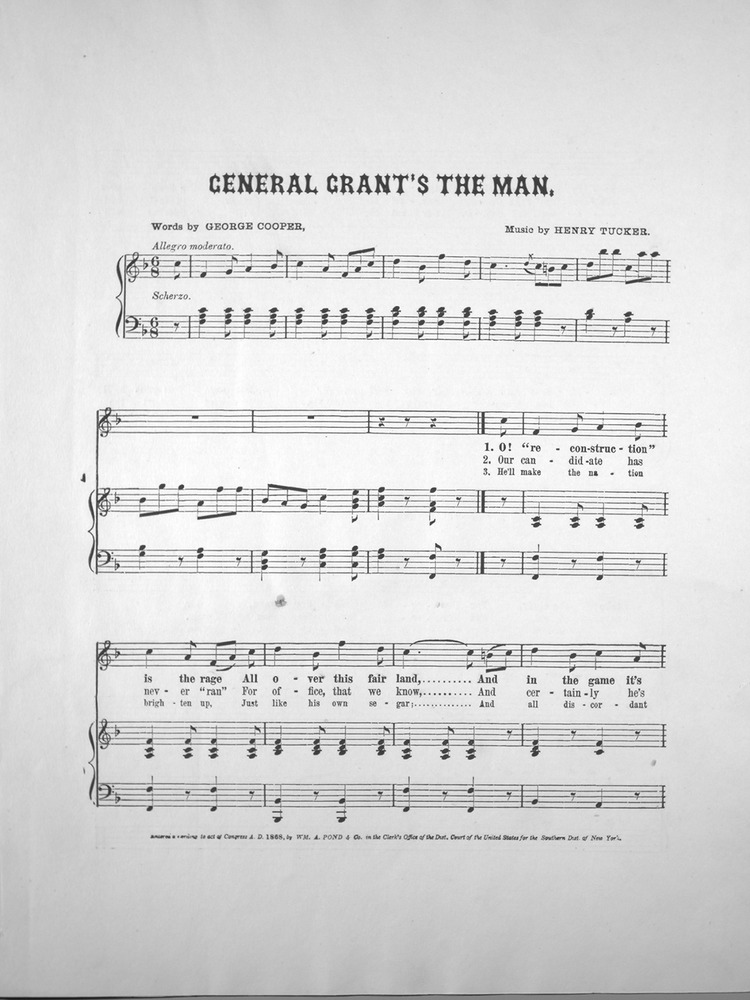

Most Freedom’s Defenders meetings were more like energetic political rallies. Sacramento had a large chapter with around a thousand members. At one event in San Francisco, attendees were encouraged to bring copies of a new song called “General Grant’s the Man,” so everyone could sing along during the gathering. As summer wore on, tensions in San Francisco began to rise. In July, after a Democratic club meeting let out, members ran into a group of Freedom’s Defenders on the street. The two sides exchanged cheers, boos, insults, and racist slurs. The situation grew heated, but the police stepped in and broke it up before it turned violent.

The Freedom’s Defenders Form in San Buenaventura

The Freedom’s Defenders officially reached San Buenaventura on July 14, 1868. The group of 27 local Republicans signed a charter, printed in red and blue on a 16-by-12-inch sheet of white paper. Created by a well-known San Francisco printer, the document featured an image of Lady Liberty holding the U.S. flag and declared that the State Council of Freedom’s Defenders authorized the creation of a local chapter, to be named “Lincoln Council, No. ___ of F.D.,” after meeting all the group’s requirements.

On the back, the charter was labeled “Pioneer Republican Club, 1868,” with W.S. Chaffee listed as president and J.A. Barry as secretary. The signatures of early Ventura Republicans, including Chaffee and Hobson, appeared alongside newer residents like Barry, Lorenzo Dow Chillson, W.D. Chillson, and Henry Spear. Just four days later, Chaffee and Hobson hosted primary voting at their homes to choose delegates for the County Union Republican Convention.

The 1868 Presidential Election

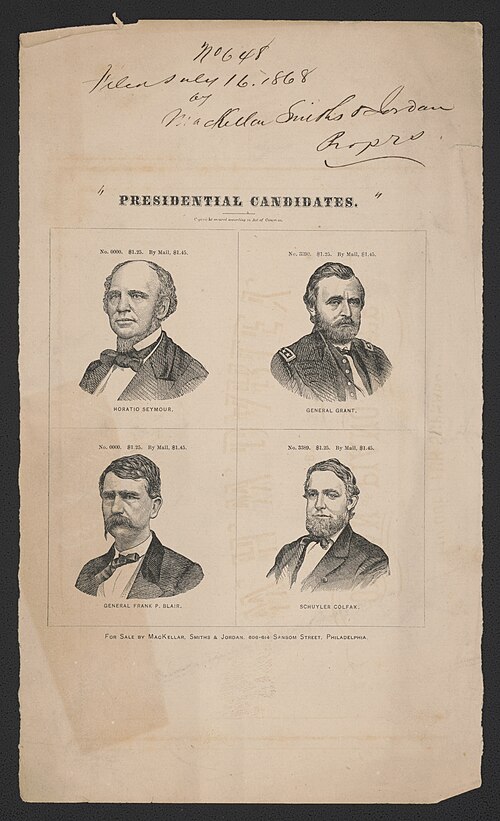

After Democrats and Republicans chose their candidates for the first presidential election since the Civil War, voters were faced with a key decision: continue the process of reunifying the country or return to old divisions. Republicans nominated Ulysses S. Grant, the hugely popular former Union general. Democrats picked Horatio Seymour, a former New York governor who wasn’t well known outside his state. Grant’s campaign supported continuing Reconstruction, giving all men equal voting rights across all states, lowering taxes, reducing the national debt, and encouraging immigration. Seymour, on the other hand, wanted to end Reconstruction, let white Southerners rebuild their governments as they saw fit, and allow states to decide who could vote. He also pushed for a single national currency, equal taxes for everyone, and getting rid of federal programs like the Freedmen’s Bureau, which had been created to assist former slaves and poor whites in the South.

The 1868 election was the first presidential race where newly freed slaves were allowed to vote. However, three former Confederate states – Mississippi, Texas, and Virginia – could not take part. They hadn’t met the requirements set by Congress for rejoining the Union, including ratifying the 14th Amendment and creating new state constitutions that guaranteed voting rights for all men, including the former slaves.

The San Francisco Examiner grew increasingly extreme in its attacks on Freedom’s Defenders. The paper claimed it had secretly obtained a song card smuggled out of one of the group’s “secret meetings.” The Examiner published lyrics it said came from the song “Stand by the Union” by James Patterson:

“A host of foreign emigrants…

Are thrown upon our shores,

Supplied with voting documents…

From Democratic stores…

The city police are on hand

With foreign brogue to aid

Their brothers from the Emerald Isle

To make a Fenian raid.”

However, no known copies of the song include these verses, suggesting the Examiner may have fabricated the lyrics to fuel fear and division.

Gorham Promotes the Republican Ticket

Newly elected Secretary of the U.S. Senate, Republican Gorham – who had lost the 1867 governor’s race partly due to his support for better treatment of Chinese immigrants – wrote a letter in August that was published in newspapers across California. He admitted that Democrats expected to win the state’s electoral votes in the upcoming November election, largely because of the Republican setbacks the year before. He warned that Democrats were trying to stir division within the Republican ranks but urged party unity. Gorham wrote that any lingering resentment should be swept away by “a generous, united, and enthusiastic support of Grant.” He expressed confidence that voters would reject the Democrats, who, he said, were still tainted by their support for the Confederacy. In September, Gorham tried to soften the controversial topic of Black suffrage, telling a crowd at the upscale Lafayette Hotel in Los Angeles that “the question of negro suffrage was not an issue in the campaign.” The Los Angeles Star blasted his remarks, calling them “sublime impudence” and accusing him of ignoring both his own past and his party’s platform. Still, Gorham stuck to his message, repeating it throughout the state during his whistle-stop and steamship campaign tour. While campaigning in Santa Cruz, Congressional candidate Pixley told a cheering crowd that last year’s Republican losses weren’t a true measure of the party’s strength. He argued that the Democratic wins in the last election were narrow and often due to voters simply choosing the “least objectionable” candidates.

The Presidential Debate for San Buenaventura Readers

In Santa Barbara, political events were more civil compared to San Francisco. At one gathering, Democratic Congressional candidate Samuel Beach Axtell spoke first, followed by a Republican speaker, allowing both party supporters to attend. The Santa Barbara Weekly Press reported that Axtell made several bold claims, including proposing that the government pay bond interest in gold. The newspaper suggested that Axtell only brought up this idea in front of a mostly Republican crowd, something he likely wouldn’t do in more Democratic cities like Los Angeles or San Diego.

In San Buenaventura, readers of the Santa Barbara Weekly Press often read political “letters to the editor” written under colorful pseudonyms like “El Cabo” and “Suggs.” Using pseudonyms was common at the time, allowing authors to express their views with more authority while avoiding potential backlash. El Cabo argued that no true patriot could support the Democratic candidates or their platform. He believed Republican Reconstruction efforts would take time to show results in the South, but that they would ultimately have lasting benefits. He also stated that only loyal men, who risked everything for their country, deserved full political rights. Suggs focused on suffrage and used anti-immigrant rhetoric to sway readers. He warned that voting for Grant and Colfax would lead to lowering the status of white Americans and bringing in more immigrants from China and Japan, who he claimed would “out-vote us three to one.”

The Santa Barbara Weekly Press raised concerns about Charles E. Pickett, a Virginia-born populist known as “Philosopher Pickett.” Pickett, a cousin of Confederate General Charles Pickett, moved to California after the Civil War and became an outspoken critic of the state’s political and economic elites. The Press claimed that Pickett, who said he was a correspondent for a San Francisco newspaper, was actually a representative of the Ku Klux Klan and a dangerous conspirator. They hinted at possible co-conspirators in Los Angeles but said they couldn’t name them due to fear of libel lawsuits. However, there is no evidence to support these claims. When Pickett died in 1882, newspapers referred to him as a “literary crank,” with the San Francisco Chronicle saying he had “one little screw loose” in his brain.

With just five weeks left in the campaign, the Santa Barbara Weekly Press started publishing letters from its San Francisco correspondent to keep local readers informed about the political battle. The Press reported that San Francisco was alive with activity, as Union supporters prepared for the fight, determined to protect the nation’s freedom from the Democrats.

Horace Greeley and Voter Fraud

The newspaper also shared advice from Horace Greeley, the influential anti-slavery founder of the New York Tribune. He recommended forming clubs in every town and creating a strong organization in each district. Greeley suggested gathering the names of all voters and inviting them to join a club. He urged that every voter who could read should receive a newspaper. He encouraged voters to vote early, ideally arriving at the polls before noon on election day. Lastly, Greeley advised district organizers to ensure that casting illegal votes would be “morally impossible.” In San Francisco, there were concerns about voter fraud, with accusations that Democrats were trying to add “fraudulent voters” to the poll lists. The San Francisco Examiner was criticized for suggesting that these voters couldn’t be questioned when challenged. At the time, the law allowed a “qualified elector and householder” or other solid evidence to challenge a person’s eligibility. If someone appeared on more than one poll list, their vote would be rejected.

Parties Try to Outdo Each Other

In October, both parties held large parades in San Francisco. On October 1, the San Francisco Chronicle described a Union rally as one of the “grandest” seen on the West Coast. Over 3,000 people, including 1,000 from the Freedom’s Defenders, marched with six bands, lighting up the route with fireworks. The crowd filled the city’s largest meeting hall, and the event lasted until after midnight. On October 13, Democrats held their own torchlight procession, drawing 4,700 people, including 3,000 on foot, 838 on horseback, and others in carriages and wagons. Governor Haight rode in a horse-drawn carriage. Marchers carried signs like “Down With Radical Republican Rule,” and soldiers and sailors marched with signs in support of a “white man’s government.” The Sonora Union Democrat criticized Republicans for inflating the size of their parade, arguing that it actually had fewer than 1,200 participants and accused them of ignoring the rise in the number of Democratic voters, which the paper claimed had increased by at least 7,000 statewide.

Just days before the election, the Santa Barbara Weekly Press printed a poem titled The Last Call that again stirred fears of the Ku Klux Klan:

“Our noble banner is unfurled,

A beacon-light to all the world:

With Grant and Colfax in the van,

Once more we’ll rout the Ku Klux Klan

And onward march to victory.”

Grant Wins the Election and California

On November 3, 1868, Grant was elected President in a landslide victory. He won 214 electoral votes while Seymour earned 80 electoral votes. While Grant won in a landslide in the Electoral College, the popular vote was much closer. Grant has earned 3,013,421 votes while Seymour won 2,706,829 votes.

California narrowly chose Grant by just over 500 votes. The Santa Barbara Weekly Press noted a turnout lower than expected, with only 729 out of over 1,100 registered voters in the county casting ballots. Despite this, nearly 60% of voters supported the Republican Grant, a strong result in a county where Lincoln had only received about 10% of the vote in 1860. In San Buenaventura, Grant got 53 votes, while Seymour received 34. The Press wasn’t surprised by the outcome, pointing to the area’s growing population of Easterners who were more energetic and forward-thinking politically compared to the rest of Southern California. Despite this shift, Santa Barbara County remained politically isolated, with neighboring counties like Los Angeles, Kern, San Bernardino, and San Diego voting Democratic.

The editors of the Santa Barbara Weekly Press urged Southern Californians to move past political divisions, saying too much time had already been lost in “factious opposition.” They called for old grudges to be set aside and encouraged unity and friendship across party lines. Meanwhile, the San Francisco Examiner offered no such olive branch. Early returns from San Francisco showed support for Seymour, leading the Examiner to expect a repeat of the Democrats’ 1867 victory. Its initial election coverage praised California as the “golden-haired daughter of Democracy.” But by the next morning, as votes tilted toward Grant, the paper turned bitter, reluctantly admitting that “the party of the Constitution and of conservative liberty… has been routed, horse, foot, and dragoon.” Sticking to its racist rhetoric, the Examiner complained, “ours is not a white man’s Government, but a Mongrelism, where white men, negroes, and China are equal.” In the following days, it questioned the election’s legitimacy, claiming many illegal votes were cast and arguing that with three Southern states still barred from voting and newly freed slaves casting ballots, the result didn’t reflect the true “voice of the people.”

Early the next year, after weeks of debate, Congress passed the Fifteenth Amendment, guaranteeing all male citizens the right to vote regardless of race, color, or previous condition of servitude. In California, Democrats – still in control of the state legislature and led by Governor Haight- strongly opposed the amendment. Haight fueled fears that it would lead to voting rights for Chinese immigrants, and both the State Assembly and Senate voted overwhelmingly to reject it. Despite California’s refusal, the amendment was ratified on February 3, 1870. California ended up being the only free state to reject both the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments. The state didn’t symbolically ratify them until nearly a century later—1959 for the Fourteenth and 1962 for the Fifteenth.

Legacy of the Freedom’s Defenders

Nearly all 27 members of San Buenaventura’s Freedom’s Defenders stayed active in local civic and political life. They were ranchers, blacksmiths, stable and saloon owners, carriage makers, carpenters, contractors, and storekeepers – and many went on to serve the community as town board presidents, justices of the peace, and school trustees. Store owner Chaffee and several other Defenders helped fund the construction of the town’s Hill School in 1872 by signing school bonds. Many left a lasting mark on the area. For example, Hobson lobbied the state Legislature in 1872 to push through the bill to create Ventura County – earning him the nickname “Father of Ventura County.” Several other early Republicans also supported the effort to break away from Santa Barbara County.

Former Freedom’s Defenders also backed major road construction projects and helped establish the nearby town of Hueneme. Freedom’s Defenders Secretary Barry served for 19 years as Ventura County Assessor. Among his papers when he died in 1925 was the original Freedom’s Defenders charter. Barry’s son Jasper presented the document to the Pioneer Museum. When the California State Library in Sacramento heard of the find, they requested a copy of the charter. According to a report in the Ventura Post, the document was photographed and forwarded to become part of the historical archives of the state.

Make History!

Support The Museum of Ventura County!

Membership

Join the Museum and you, your family, and guests will enjoy all the special benefits that make being a member of the Museum of Ventura County so worthwhile.

Support

Your donation will help support our online initiatives, keep exhibitions open and evolving, protect collections, and support education programs.

Bibliography

- “1860 United States Presidential Election.” Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia. Last modified December 5, 2023. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1860_United_States_presidential_election.

- “1868 United States Presidential Election in California.” Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia. Last modified March 24, 2025. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1868_United_States_presidential_election_in_California.

- “African American Voting Rights | Voters and Voting Rights | Presidential Elections and Voting in U.S. History | Classroom Materials at the Library of Congress | Library of Congress.” The Library of Congress. Accessed April 23, 2025. https://www.loc.gov/classroom-materials/elections/voters/african-americans/.

- Anderson, Susan. “California, a “Free State” Sanctioned Slavery.” California Historical Society. Last modified April 3, 2020. https://californiahistoricalsociety.org/blog/california-a-free-state-sanctioned-slavery/.

- Appeal-Democrat (Marysville, CA). “Letter from San Francisco.” January 18, 1868, 1.

- Appeal-Democrat (Marysville, CA). “Freedom’s Defenders.” March 29, 1868, 3.

- “Column: California’s Shameful Vote Against Black Suffrage in 1870 — and Why It Still Matters Today.” Los Angeles Times. Last modified February 28, 2021. https://www.latimes.com/opinion/story/2021-02-28/1870-black-vote-fifteenth-amendment.

- “Contributor: California’s Never-ending Secessionist Movement — and Its Grim Ties to Slavery in the State.” Los Angeles Times. Last modified August 7, 2022. https://www.latimes.com/opinion/story/2022-08-07/secession-san-bernardino-slavery-history-california.

- Daily Evening Herald (Stockton, CA). “Freedom’s Defenders.” April 10, 1868.

- Daily Miner-Transcript (Nevada City, CA). “The Democratic Convention.” May 1, 1868, 2.

- Dogmo Studios | Eliza Wee | @ewee. “Peter Hardeman Burnett – Gold Chains: The Hidden History of Slavery in California | ACLU NorCal.” ACLU of Northern CA. Last modified June 28, 2018. https://www.aclunc.org/sites/goldchains/explore/peter-burnett.html.

- “The Election of 1868.” American Battlefield Trust. Last modified March 25, 2021. https://www.battlefields.org/learn/articles/election-1868.

- “Emperor Norton at a Pro-Civil Rights Lecture, March 1868.” The Emperor Norton Trust. Last modified April 2, 2020. https://emperornortontrust.org/blog/2019/2/24/emperor-norton-at-a-pro-civil-rights-lecture-march-1868.

- “Fireman’s Fund – Our People: John Stratman.” Fireman’s Fund Heritage Server. Accessed April 23, 2025. https://www.ffic-heritageserver.com/people/people23.htm.

- Flint, Anna. “Oral history interview with Anna Flint.” By Mary Johnston/Ventura County Museum of History and Art. Audio. April 17, 1984.

- Folsom Telegraph. “Secret Political Societies.” March 14, 1868, 2.

- “General Grant’s the Man! : Song and Chorus / Words by J. Stratman ; Music by S.T.” Digital Collections. Accessed April 23, 2025. https://digicoll.lib.berkeley.edu/record/99376?v=uv#?xywh=-457%2C0%2C2077%2C1499&cv=2.

- “Google Search.” Google. Accessed April 23, 2025. https://www.google.com/search?client=firefox-b-1-d&q=politics+of+the+San+Francisco+Examiner+in+the+1860s.

- “Henry Huntly Haight.” Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia. Last modified April 8, 2025. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Henry_Huntly_Haight#:~:text=Henry%20Huntly%20Haight%20(May%2020,%2C%20to%20December%208%2C%201871.

- “A Historical Analysis of Racism Within the US Presidency: Implications for African Americans and the Political Process.” PMC Home. Accessed April 23, 2025. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8250541/.

- “How the 15th Amendment Came to Los Angeles.” PBS SoCal. Last modified March 26, 2025. https://www.pbssocal.org/shows/lost-la/how-the-15th-amendment-came-to-los-angeles.

- “The Ku Klux Klan and Violence at the Polls.” Bill of Rights Institute. Accessed April 23, 2025. https://billofrightsinstitute.org/essays/the-ku-klux-klan-and-violence-at-the-polls.

- “Los Angeles: The Civil War’s Forgotten Front.” The Gettysburg Compiler. Last modified September 28, 2022. https://gettysburgcompiler.org/2022/09/28/los-angeles-the-civil-wars-forgotten-front/.

- Martinez News-Gazette. “Freedom’s Defenders.” May 30, 1868, 2.

- Martinez News-Gazette. “Grand Demonstrative Meeting.” August 29, 1868, 2.

- Martinez News-Gazette. “The San Francisco Demonstration.” October 24, 1868, 2.

- “National Union Party (United States).” Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia. Last modified April 14, 2025. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/National_Union_Party_(United_States).

- “Our Dishonorable Past: KKK’s Western Roots Date to 1868.” Cascade PBS. Last modified March 20, 2017. https://www.cascadepbs.org/2017/03/history-you-might-not-want-to-know-the-kkks-deep-local-roots-west-california-washington-oregon.

- Petaluma Weekly Argus. “Prepare for the Campaign.” January 16, 1868, 2.

- Pfaelzer, Jean. California, a Slave State. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2023.

- “Population of Civil Divisions Less Than Counties – California.” 1870 U.S. Census Data. Accessed April 23, 2025. https://www2.census.gov/library/publications/decennial/1870/population/1870a-12.pdf.

- “Population of the United States, State of California.” Index of 1860 U.S. Census Data. Accessed April 23, 2025. https://www2.census.gov/library/publications/decennial/1860/population/1860a-06.pdf.

- “The Project Gutenberg Ebook of Beadle’s Dime Song Book No. 2.” Free eBooks | Project Gutenberg. Accessed April 23, 2025. https://www.gutenberg.org/files/49628/49628-h/49628-h.htm.

- “The Republican Party in California, 1856-1868.” Accessed April 23, 2025. https://repository.arizona.edu/handle/10150/288108.

- Ricard, Herbert F. “Charter Members of the Lincoln Council of Freedom’s Defenders.” Ventura County Historical Society Quarterl 22, no. 3 (Spring 1977), 14-25.

- Sacramento Bee. “Freedom’s Defenders.” September 13, 1867, 2.

- Sacramento Bee. “Freedom’s Defenders.” January 16, 1868, 2.

- Sacramento Bee. “Local News.” August 26, 1868, 3.

- Sacramento Bee. “Major Jack Stratman.” April 3, 1868, 2.

- Sacramento Bee. “R. G. Gaskill.” June 16, 1868, 3.

- Sacramento Bee. “The Campaign.” June 11, 1868, 2.

- San Francisco Chronicle. “A Political Event.” October 1, 1868, 3.

- San Francisco Chronicle. “Freedom’s Defenders.” June 10, 1868, 3.

- San Francisco Chronicle. “Grand Political Demonstration.” October 13, 1868, 3.

- San Francisco Chronicle. “Illegal Voting.” November 10, 1868, 2.

- San Francisco Chronicle. “No Questions Asked.” November 3, 1868, 2.

- San Francisco Chronicle. “Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Meeting.” October 2, 1868, 3.

- San Francisco Chronicle. “The Defenders of Freedom and the Impeachment Resolutions.” March 6, 1868, 2.

- San Francisco Chronicle. “Wherefore?” March 4, 1868, 2.

- San Francisco Examiner. “”Freedom’s Defenders”.” September 12, 1867, 3.

- San Francisco Examiner. “A ‘Freeluncher’s’ Song.” July 29, 1868, 2.

- San Francisco Examiner. “A Falling Temple.” January 11, 1868, 2.

- San Francisco Examiner. “Afraid of Him.” September 20, 1867, 2.

- San Francisco Examiner. “Defenders of Freedom.” September 13, 1867, 2.

- San Francisco Examiner. “Democratic Meeting.” April 2, 1868, 3.

- San Francisco Examiner. “How It Works.” November 3, 1868, 2.

- San Francisco Examiner. “Much Exercised.” April 24, 1868, 2.

- San Francisco Examiner. “Political Cowards.” September 17, 1867, 2.

- San Francisco Examiner. “The Time for Action.” March 7, 1868, 2.

- San Francisco Examiner. “Work For Democrats.” November 9, 1868, 2.

- Santa Barbara Weekly Press. “”The Last Call”.” October 31, 1868, 1.

- Santa Barbara Weekly Press. “Another Shot.” September 12, 1868, 2.

- Santa Barbara Weekly Press. “Be Friends.” November 14, 1868, 2.

- Santa Barbara Weekly Press. “Democratic Speaking/Republican Meeting.” October 24, 1868, 2.

- Santa Barbara Weekly Press. “Notice.” July 18, 1868, 3.

- Santa Barbara Weekly Press. “Official Returns.” November 14, 1868, 2.

- Santa Barbara Weekly Press. “Political.” August 29, 1868, 2.

- Santa Barbara Weekly Press. “Political.” August 15, 1868, 3.

- Santa Barbara Weekly Press. “San Francisco Letter (From Our Correspondent).” October 3, 1868, 3.

- Santa Barbara Weekly Press. “The Election.” November 7, 1868, 2.

- Santa Barbara Weekly Press. “The Result.” November 14, 1868, 1.

- Santa Cruz Weekly Sentinel. “Grant and Colfax Club.” August 15, 1868, 2.

- Shaffer, Ralph E. “California Reluctantly Implements the Fifteenth Amendment: White Californians Respond to Black Suffrage.” Cal Poly Pomona. Last modified 2020. https://www.cpp.edu/class/history/docs/shaffer15thamend.pdf.

- Shasta Courier. “Inconsistent.” April 18, 1868, 2.

- Shasta Courier. “Letter from George C. Gorham.” August 8, 1868, 2.

- Shasta Courier. “Monster Rally.” October 10, 1868, 2.

- Sheridan, E. M. “Early County Republicans Unpopular; Met in Secret.” Ventura County Star, November 25, 1929, 18.

- Sheridan, E. M. “State Wants Copy of Rare Relic in Pioneer Museum.” Ventura Post, December 9, 1925.

- Sheridan, Solomon N. History of Ventura County, California, Volume I. Chicago: S. J. Clark Publishing Co., 1926.

- Sheridan, Solomon N. History of Ventura County, California, Volume II. Chicago: S. J. Clark Publishing Co., 1926.

- Smith, Stacey. “Pacific Bound: California’s 1852 Fugitive Slave Law.” BlackPast.org. Last modified January 7, 2014. https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/pacific-bound-california-s-1852-fugitive-slave-law/.

- “These Were the Biggest Cities in California 150 Years Ago.” KRON4.com. Accessed June/July 7, 2022. https://www.kron4.com/news/these-were-the-biggest-cities-in-california-150-years-ago/.

- Trinity Journal (Weaverville, CA). “Get Ready to Organize.” June 6, 1868, 2.

- Trinity Journal (Weaverville, CA). “Handsome Present.” April 25, 1868, 2.

- Union Democrat (Sonora, CA). “Deceiving Themselves.” October 17, 1868, 1.

- Union Democrat (Sonora, CA). “Don’t Understand His Platform.” June 6, 1868, 1.

- Ventura County Resource Management Agency – Ventura County Resource Management Agency. Accessed April 23, 2025. https://vcrma.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/1850-2000-historical-census-population-of-places-towns-and-cities-in-california.pdf.

- Ventura Free Press. “John A. Barry Passes After Long Career.” July 29, 1925.

- Waite, Kevin. “California’s Forgotten Confederate History.” The New Republic. Last modified May 11, 2021. https://newrepublic.com/article/154777/californias-forgotten-confederate-history.

- Weekly Argus (Petaluma, CA). “Sympathy.” March 26, 1868, 2.

- “When Did African Americans Actually Get the Right to Vote?” History. Last modified January 29, 2020. https://www.history.com/news/african-american-voting-right-15th-amendment.