By Eugene Foster Percy

In this nugget, we get a glimpse of the social changes brought on by the automobile on Ventura Avenue. Eugene Foster Percy shares his earliest memories of riding in his grandmother’s car (sitting on the floorboards if you can believe it) and all the near misses as everyone collectively got a literal crash course in how to operate a vehicle. This tale includes harrowing turns on mountain roads, a surprisingly lax view on DUIs, and a whole lot of anxiety-inducing disregard for automobile safety that we would find shocking today. This article was taken from the MVC Quarterly Volume 23, Number 2 (Winter 1978) and originally edited by Grant W. Heil.

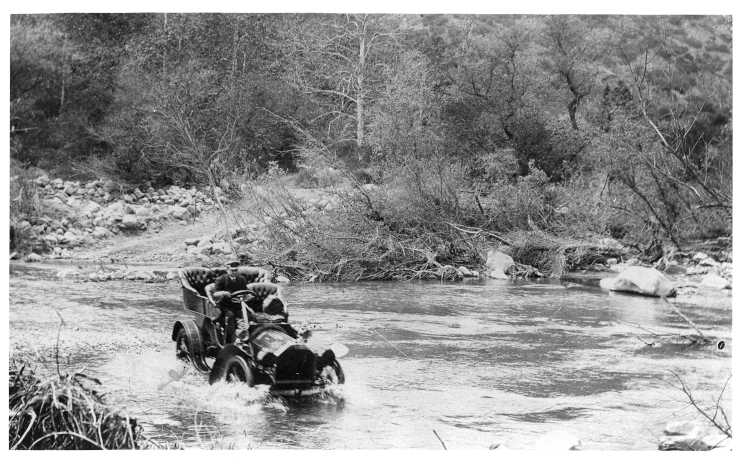

PN274, John Calvin Brewster, MVC Library & Archives collection.

Automobiles arrived in Ventura County before I did. Thomas E. Cunnane, M.D., who assisted in my arrival, told my folks they should buy an automobile instead of a baby buggy since from his experience babies liked the fast motion of an automobile better than the slow movement of a baby carriage. Being a $75 a month bank employee at that time, my father had to satisfy his family with a horse and buggy.

My maternal grandfather, Eugene Preston (E. P.) Foster, had a four-cylinder Maxwell touring car, the first automobile I was aware of. It was a right-hand drive without a windshield or top. There were kerosene carriage lamps on each side of the dashboard and carbide headlights, but no doors on either side of the two front seats; of course, it had to be cranked and the horn was a rubber bulb that you squeezed. The back seat was called the tonneau because there were doors on each side and its floor was a nice place for sleepy children. Sometime about 1910 Grandfather and Grandmother drove the Maxwell to San Jose where my father, mother, baby sister, and I caught up with them by train; and we toured some of the northern part of the state. Grandfather repeated the story of that trip over and over again to us children so that the memory of what I saw remains imprinted in my mind to this day.

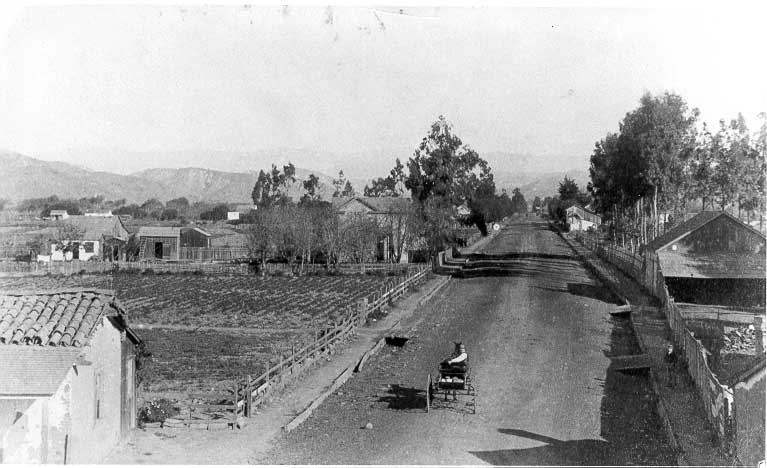

If you lived in town and owned an automobile, you probably got along without a horse and buggy. The Ventura Avenue had been oiled out as far as the city limits, about a mile north of Main Street. And, if I recall correctly, Main was oiled a little way east but from there on the roads were dirt dry in the summer and wet in the winter. The county ran a sprinkling wagon from the city limits up through Foster Park when it was dry; but when it was wet (that is, very wet) those who lived out of town got out their horses and buggies. Many of those horses could be ridden or driven. Grandfather drove Sam, a black gelding, to the bank (National Bank of Ventura); my father rode our brown mare, Gyp; and Uncle Henry Neel drove a gray mare, Patsy. They left them at the livery stable on Oak Street opposite to where the Great Eastern is today. The bank was on the southwest corner of Oak and Main Streets.

There were no culverts in the road from the Avenue School south to the city limits that I was ever aware of; so, when the gutter on the east side of the road became overloaded, the water ran across the road in the direction of the river and ended by making some good size mud holes. The road above and below might be dry enough to travel with a car, but the mud holes would seem to last from one rain until the next. If an automobile driver managed to negotiate the mud holes without having to be pulled out by a team of horses, he thought he had something to brag about. I remember one mud hole was just below Hyde Chaffee’s house in that section where the Foster School is today. The solution to the mud holes was to gravel them, but the gravel came from the riverbed and was hauled in wagons with two-by-four bottoms, which were dumped by removing one board at a time. A slow process, but even slower was loading with a pick and shovel. Sometimes a good gravel bed without too many larger rocks would be hard to find in the river in a heavy rainy season.

Grandmother Foster was an active club woman. As far back as I can remember she always had a cook and Aunt Pearl looked after the housekeeping, so Grandmother had time to be on committees with this or that club. Since Sam and the buggy were just too slow, Grandfather bought her a two-cylinder runabout. The first trouble they had with it was the timing: even with the spark lever delayed, it would kick back enough to wrench her shoulder and it took a few visits to the garage before they finally adjusted it. Grandmother’s next troubles concerned some of the telephone poles on the street corners in town, but she finally broke herself from turning before she arrived at the corner. Grandfather pointed out some of the telephone poles she had left her mark on. I was with Aunt Pearl coming home from town one day when something went wrong with the steering gear of the little Maxwell and we headed out into Carl Vince’s bean field. Unsafe at any speed had not been published, but the little Maxwell would have qualified.

The final episode that queered me from riding in that Maxwell occurred one day when I went with my mother and grandmother to pick up my cousin, Bob Baker, who was an infant in arms. His mother (Mrs. Neill Baker) was going to a party. Grandmother was driving and Mother held Bobby while I sat on the floor on the left-hand side with my feet on the running board as the bucket seats did not have any space between them. We were coming down Main Street traveling west when the Ewings came down Chestnut Street on their way to catch a train. They were being driven by their son. They had entered the intersection; but Grandmother, instead of slowing down and turning in behind them, on impulse stepped on the gas and swung to the left-hand side of the street in front of them. They were not going fast but the son had turned his head around to speak to his mother in the back seat. He struck the Maxwell broadside. Just before they collided Grandmother shouted, “Look out!” When I felt the bump, I lit running to get out of the way, and as I looked back over my shoulder I saw Mother lying in the street holding Bobby at arm’s length to keep him out of harm’s way. Grandmother was landing on her hands and knees beside her. Ed Mercer’s garage was on the southeast corner of Main and Chestnut so the little Maxwell was tipped back on its wheels and rolled into the garage. Grandfather came from the bank and took us home. I was at Grandmother’s house the afternoon that Mrs. Ewing called to see if she had been hurt and to apologize for her son not looking where he was going. Their car must have suffered some damage as they had missed the train. I do not ever remember Grandmother driving after that, but Aunt Pearl and Aunt Mildred used the little Maxwell until it was finally replaced by a Dodge roadster.

My father and mother bought a car shortly before the last episode with the Maxwell. It was a Regal underslung. The one big talking point for it was that it would not tip over, but on the other hand you had to keep the wheels out of the ruts as its road clearance was about the same as present day cars. It had a windshield which was termed a “glass front” at that time and four doors (only three of them opened). There were electric lights and horn, but no generator to charge the battery. It had to be taken to town to have that done. (The automobiles with carbide lights had to have their acetylene cylinders exchanged the same way.)

Grandfather and Grandmother went to Los Angeles for a few days in 1912, and when they came home, they were driving a seven-passenger Winton Six with a “glass front” top and four doors (Grandfather never put up the top). It also had a self-starter which was a tank full of compressed air that forced each cylinder down when it was time for the power stroke to make the engine turn over. The tank must have held only enough air for one power stroke per cylinder; after that, you ran out of air and had to get the crank out of the toolbox between the two front seats. You also had to remember to engage the compressor and build up pressure before you stopped the engine or there would be no self-starter the next time. That air tank was also handy for inflating tires after fixing a puncture, which was quite common. The Winton also had a fourth gear that was an overdrive. If the road was level and smooth enough and you got up enough speed, it could be shifted to overdrive; and the 48 HP that the engine was rated at would maintain the momentum. Like our Regal it also had electric lights and horn, a very commanding one for the time. I think that the Winton must have had a generator to charge the battery as the horn was always in good working order.

Since Grandfather did not want to take his hand off the steering wheel to press the horn button, which was down on the steering post, he gave Grandmother that job. He had the button moved to the front side of the toolbox; and to be sure of making contact, another button was on the floorboards where she could press it with her foot. Going over the old Casitas Pass Road to Santa Barbara, she gave it quite a workout. One Sunday we had been up to Goleta to visit Aunt Lucy and Uncle Joe Sexton. Aunt Lucy was Grandfather’s sister. This was shortly after the Rincon had been paved, and the pavement was not too wide, about 18 feet. Grandfather got up momentum and shifted into overdrive and was going along whistling a tune when two cars ahead, one starting to pass the other, pulled abreast. Grandfather said, “Blow the horn, Mother”, and she did. Both cars hit the dirt on each side of the road and we sailed through in between; he never lost momentum.

Being indoors at the bank made Grandfather appreciate the outdoors enough so that he never wanted to put the Winton top up. At times when the sun was hot or the road was dusty, there was some agitation on the part of the women folks for a little shade. In Los Angeles there were a few cars that were driven by chauffeurs which had what was called “Victoria tops”; society people rode in the back seat shaded by a top that looked like an overgrown baby buggy cover. Grandfather had one of these put on the Winton so that those who wanted it could have shade. He stayed out in the open. That “Victoria top” made a wonderful wind scoop and cut down on the mileage he got with the Winton so he turned to using distillate, a fuel employed in early tractors and stationary gas engines and considerably cheaper than gasolene [sic]. The engine had to be started on gasolene from a reserve tank under the dash, then was switched over to distillate by opening and closing valves. When the engine cooled off, the carburetor had to be drained before gasolene was let in for starting (another process no one would want to bother with today).

Grandfather and I were red-green color blind. And when he first got the Winton, all we knew was that it was a dark shade. I asked my mother what the color was and she told me it was dark red. When it came time to have it repainted, Grandfather selected a lemon yellow with black trim on the edges of the fenders. Considering some of the colors you see on present day cars, he was way ahead of his time. I remember asking Grandfather what kind of car he was going to buy next time. His answer was pessimistic about himself and optimistic about the Winton, because he thought it would last the rest of his life. When all the son-in-laws had their own cars, the seven-passenger Winton was not needed so often. Then he bought a four-passenger Winton roadster which was always referred to as the “little Winton,” and the “big Winton” became sort of a utility wagon. When the Winton motorcar became obsolete, he bought a couple Rickenbacker cars, a sedan for Grandmother and Aunt Pearl, and a roadster for himself; but riding in the sedan convinced him that it was time to come in from outdoors and he exchanged it for a coupe. As an automobile the Rickenbacker hardly got off the ground before it became obsolete; and when parts became hard to get, he switched to Pierce Arrow. It too has now joined the ranks of vintage cars.

Fred Wadleigh was one automobile driver that announced himself when he came to town. The Rancho Casitas in some of my early recollections was known as the Wadleigh ranch. While working for the Hoffmans, the late Alfonso Vanegas occupied the house that the Wadleighs had lived in. Fred had a brass whistle (much on the order of the steam whistle) connected to the exhaust pipe just behind the manifold, and the faster the engine ran, the louder the whistle. He drove about as fast as the cars and the roads at that time would let him. He saluted everyone along the way, and he must have known nearly everyone as the whistle would be blowing long before he reached our neighborhood. Fred probably blew for Ed Canet, Denny Barnard, Allen Fraser, and Louis Hartman. At Gosnell Hill (or Two-Mile Bend) he would give a prolonged blast because originally the turn was almost a right-angled blind corner and his sister-in-law, married to Ira Gosnell, lived in the house on the hill. And it seemed he kept it blowing till he passed his father-in-law Lloyd Selby’s house a little further down the Avenue. My father got an exhaust whistle for our Regal; but he did not drive as fast as Fred Wadleigh. The Regal did not have as much power and my father was not the noisy type. Nevertheless, when you were riding in an automobile with such a whistle, it could be quite shrill on the ear drums. It was a supplement to the electric horn on the Regal when the storage battery was low. But the whistle would carbon up and lose its resonance and had to be taken off and cleaned. Fred Wadleigh must have tired of keeping it clean, or else he traded off the car and the whistle with it because his trips to town were not as noticeable after a while.

Ed Canet, who owned the Rancho Cañada Larga o Verde, was a very likeable person when sober, but periodically would drink too much. One evening shortly after my father and mother had bought their first car, we had gone for a ride about dusk up towards Foster Park and on our return passed a car with lights on, weaving all over the road. Along our way home we stopped at Louis Kohl’s, who lived on the opposite side of the road from Carl Hartman’s house. He was a small-time butcher and meat peddler, and perhaps Louis had bought an animal from Ed. He had just been there. Louis asked my father if we had met Ed Canet on the road, and Father said he must have been the one who was weaving. Then Louis told Father about their conversation, which must have gone like this:

“It is getting dark Ed; you better light your lights.”

“I don’t need lights, I got eyes like a cat.”

“I know you have Ed, but other people don’t, and you wouldn’t want them running into you.”

“That is right,” said Ed, “better light my lights.”

So, Louis got out a match and lit the acetylene headlights.

The train to Nordhoff in its earlier days gave service night and morning. It spent the night at Nordhoff, where there was a turntable for the locomotive, and left early in the morning for Ventura. Sometimes in winter when it was dark we could see the lights in the coach as it went by the lower end of our place. It turned at the Y at Montalvo and returned to Nordhoff before noon, then down from Nordhoff after lunch and back to Nordhoff in the evening to spend the night. Mrs. Canet would sometimes take the train from Ventura back to the ranch. There was a siding called Weldons just back of the Canet ranch barn, so she did not have far to walk. There was another siding up the track away called Canet, then La Crosse, Oak View, Tico, Matilija, and Nordhoff. Nordhoff was the name of the town within the Ojai Valley. When my sister and I were still youngsters, Father drove Mother and us in the horse and buggy to Wheeler Hot Springs where Mother and we children spent several days there; then we left Wheelers via four-horse stage to the Matilija station, where we caught the train to Chrisman, referred to then as the Gas Plant, where Father met us. The Southern Pacific ran two night trains between Los Angeles and San Francisco. The one that went up the valley was called the “Owl” and the one that went up the coast was called the “Lark”; the Nordhoff train was dubbed by some of us locals as the “Buzzard.”

Sometime about 1914 to 1917 there was a campaign for “Good Roads” and a bond issue was voted on and passed. I do not know the year they started paving Ventura Avenue, but it seemed like a slow process. For kids living on the Avenue with a dirt path along one side, roller skates were out; but that did not keep us from wishing after seeing the kids in town skating on the cement sidewalks. We were waiting eagerly for any kind of cement so we could try out some skates ourselves.

The equipment for paving the road consisted of a one-cylinder road roller, a harrow and drag, a self-moving cement mixer that must have covered about half a yard at a time, about four wheel barrows, and about eight or 10 teams with dump wagons and eight men working with the cement mixer. The roller pulled the harrow to loosen the dirt, then pulled the drag to level up the surface; and after two-by-four forms had been put in place, the loose dirt between was packed by the roller. The wagons left piles of sand and gravel and sacks of cement ahead of the cement mixer. The gravel was then shoveled into the wheelbarrows and moved by hand into the mixer. There was no reinforcement steel used in the pavement. The four inches of cement would keep the road smooth, dustless and no longer boggy in wet weather. After the concrete behind the cement mixer hardened, they covered it with dirt and built dikes to hold pools of water until it cured. To those of us waiting to enjoy the paving it seemed to take an awfully long time. Traffic had to keep to the side; and occasionally a dike would break during the night and the water would run into the dirt shoulder where the daily run would churn up mudholes. The paving finally cured and all the kids on the Avenue bought roller skates. Traffic was not so heavy that the pavement could not be shared among horses and wagons, automobiles, and kids on roller skates, with considerable dirt on both sides for saddle horses.

When the county laid down the four inches of concrete, no one foresaw the oil boom that would come. While the wildcat wells drilled with standard tools were in vogue, the thin surface was subjected to no great load; but when the oil companies changed over to rotary rigs, they needed lots of mud and they hauled it from the Selby place where Rocklite later located. The trucks had solid rubber tires and hauled all they could hold; and it was not long before the original cement slab began breaking up. And the Avenue which had been a rural community also cracked up.